#67 (tie): ‘The Red Shoes’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Technicolor passions flare up on and off the ballet stage in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's signature achievement.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

The Red Shoes (1948)

Dir. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

Ranking: #67 (tie)

Previous rankings: #121 (2012).

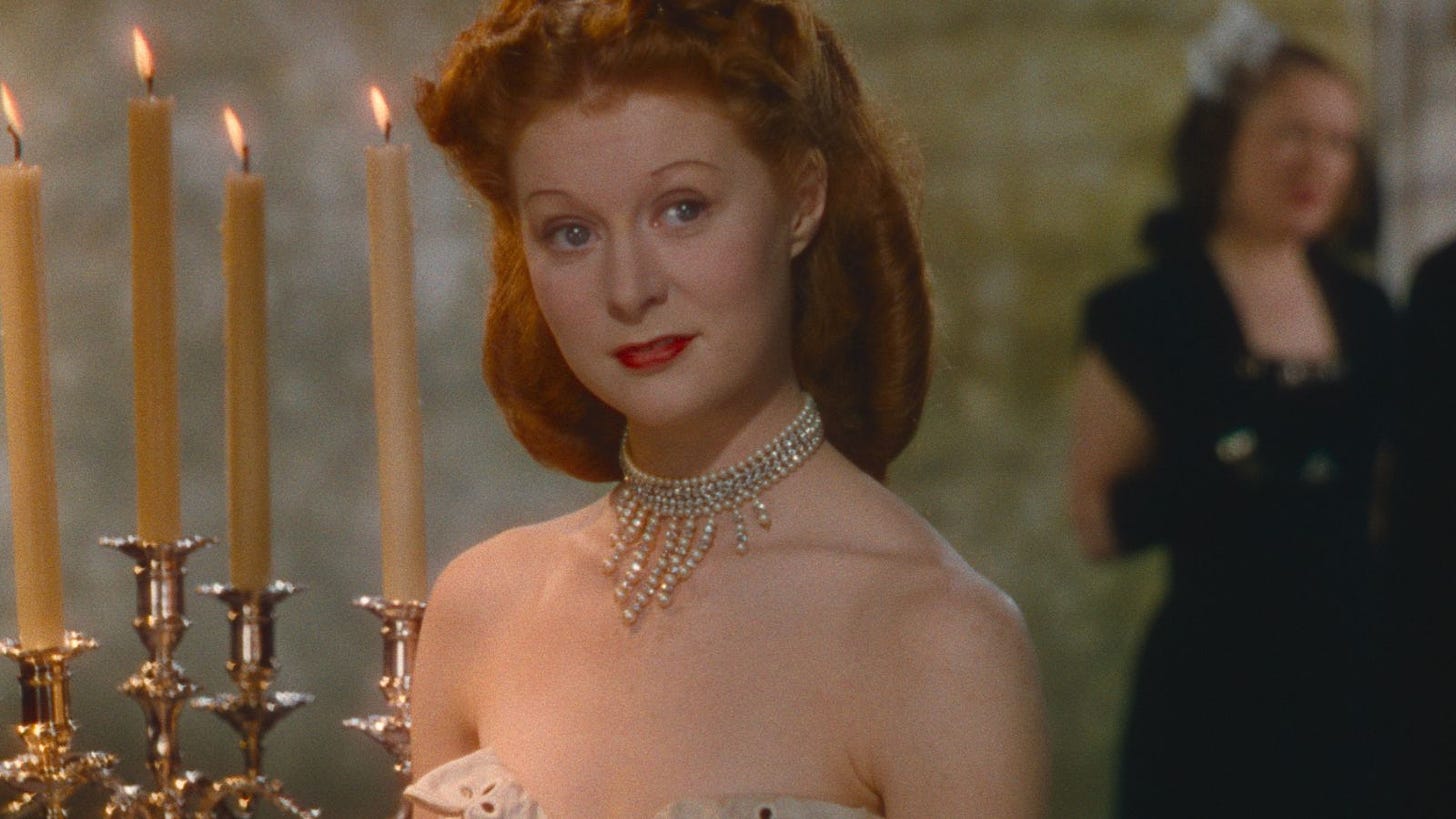

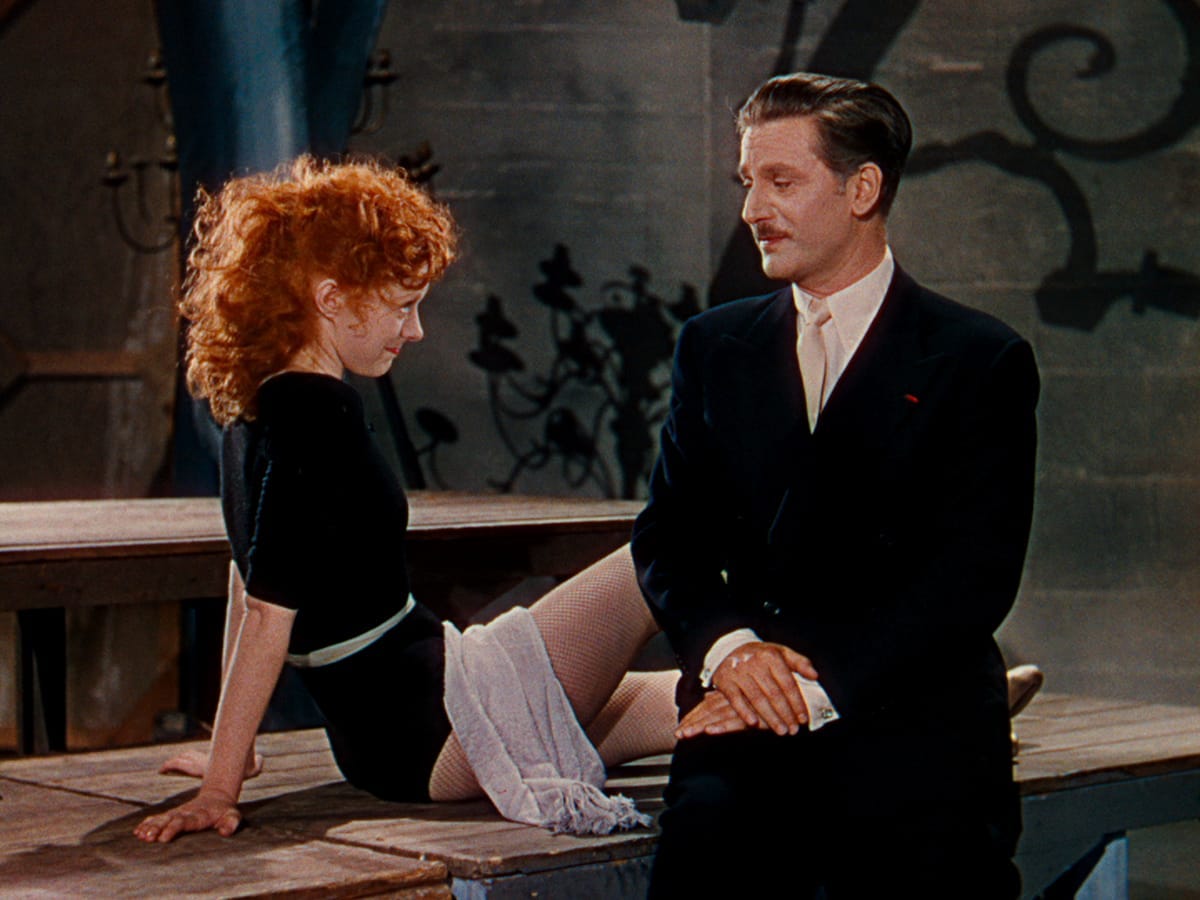

Premise: Under the impeccable eye of Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), the shrewd and obsessive leader of the world-renowned Ballet Lermontov, two up-and-coming talents flourish at the same time. One is Victoria Page (Moira Shearer), a ballerina fiercely devoted to her craft, and the other is Julian Craster (Marius Goring), a composer who quickly establishes himself in the company after a stint coaching the orchestra. Victoria and Julian’s stars rise together when he composes an original ballet around the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale “The Red Shoes” and she galvanizes the opening-night crowd with her performance as prima ballerina. But when Victoria and Julian’s creative collaboration leads to romance, the possessive Boris steps in and seeks to sabotage the relationship, forcing Victoria to choose between her love of dance and a marriage that might lead to her falling short of her potential.

Scott: Keith, in the lead-up to our discussion of The Red Shoes, the Gene Siskel Film Center hosted a special screening of the film as part of its series on Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, with Martin Scorsese’s longtime editor (and Powell’s widow) Thelma Schoonmaker in attending for a post-screening conversation. You were able to attend that screening with your family—I, on the other hand, flaked on buying a ticket before it sold out—so I’m curious to hear your thoughts on that experience. But it occurs to me now how much Scorsese’s advocacy for The Red Shoes, which he’s consistently placed among his five favorite films, has made a difference in how much the film (and Powell and Pressburger’s work in general) has been embraced over the years.

I reviewed the Scorsese-narrated documentary Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger over the summer and I was struck by how badly their films had fallen out of favor until the Scorsese-led wave of American directors in the ‘70s professed a deep admiration for their work. When the Powell/Pressburger collaboration peaked with The Red Shoes in 1948 and tapered off significantly in the years that followed—though 1951’s The Tales of Hoffmann was sort of retroactively placed in their classics era—they seemed to drop into obscurity, looking conspicuously out of place among a new generation of British directors, like Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson, that owed more to the French New Wave. I was surprised to learn in the documentary that Powell, having torched his reputation as a solo director on Peeping Tom in 1960, genuinely had to be tracked down and rediscovered by admirers like Scorsese. We can see by previous editions of the Sight & Sound poll that Powell and Pressburger films were a non-presence until 2012, when The Red Shoes was only at #121 and nothing else of theirs made the list. Now they have five in the Top 200: We already talked about A Matter of Life and Death at #78, and Black Narcissus, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and I Know Where I’m Going are all in the mix.

To which I say: Huzzah! The Red Shoes is, I think, rightly placed a small notch above the rest, but the ascendance of Powell and Pressburger’s films is a good example of how critical advocacy (and filmmaker advocacy, in Scorsese’s case) can rescue important work from obscurity. Certain directors have trouble gaining traction due to cultural timing—Carl Dreyer, whose films all feel wildly out of time and fashion, is maybe the prominent example of this—but it’s hard to believe that the expressive, Technicolor punch of The Red Shoes could ever fall out of favor. You don’t necessarily associate British cinema with emotion, but even when you’re confronted with seemingly reserved characters, like David Niven in A Matter of Life and Death or Anton Walbrook’s Lermontov here, there’s so much passion underneath the surface. After all, the affection Niven’s pilot generates for a radio operator as his plane is going down literally spares his life, and though Lermontov’s obsession with Moira Shearer’s Victoria here isn’t romantic, it runs hot. And so does the film.

To me, the most important exchange to The Red Shoes thematically comes when Lermontov asks Victoria why she wants to dance and her answer is, “Why do you want to live?” Lermontov is taken aback by her response, but identifies with her strongly. He simply “must” do what he does, which is to run this ballet company and put on the best shows possible. His faith in Victoria’s talent is calcified by his understanding that she shares the same creative drive. In his mind, they will go to extraordinary heights together because the ballet will be an all-consuming and sustaining pursuit for both of them. He seems to expect that of Julian, too, as payback for his faith in him as well. Their romantic relationship is an unforgivable betrayal of a tacit agreement Lermontov has with Victoria and Julian, even if we in the audience recognize it as the most human possible thing. It’s certainly not the first time that a close creative collaboration has led to private intimacies.

The threading of this love triangle into a production of The Red Shoes—a ballet based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, composed by Julian and produced by Lermontov with Victoria as prima ballerina—is just so breathtakingly elegant, isn’t it? The dream of these red shoes, a symbol of a dancer’s highest aspiration, turned into a curse when she cannot remove them sets the film on a course to tragedy. All three characters are beautifully drawn, but The Red Shoes is a film that shows rather than tells, in that so much comes through in movement and facial expression instead of dialogue, even when Victoria isn’t on stage. It’s not like I wouldn’t want to hear the film, but you could theoretically turn the sound off and get all the information you need in the intensity of the actor’s faces in close-up or the many filmic ways Powell and Pressburger express emotion.

So how was that Schoonmaker screening, Keith? What did you learn from that and from seeing the film projected (which I never have)? Would this be the Powell/Pressburger production you’d place above all others, too?

Keith: I don’t want to rub it in, Scott, but it was pretty great. I’d never seen The Red Shoes projected before, and to do so with Schoonmaker in attendance in a packed house was one of those moviegoing experiences you wish every moviegoing experience could be. (Put another way: a rapt crowd watching a masterpiece followed by a Q&A with one of the directors’ widows who’s a legend in her own right > watching Beetlejuice Beetlejuice in a poorly kept-up multiplex where half the audiences is on their phones and the other half is talking.) But here’s what really stands out for me: when the ballet sequence ended, the audience applauded. I can’t think of another movie in which that’s happened, no matter how bravura the sequence or stunning the moment. Nobody applauded at There Will Be Blood’s “I abandoned my boy” scene. I didn’t hear any clapping when Casey Affleck tells Michelle Williams “I can’t beat it” in Manchester by the Sea. So why is this different?

I think the obvious answer is that it’s a discrete performance in the middle of the film and one that depends on the talent of its stars to pull it off. Powell and Pressburger hired Shearer because they wanted a professional dancer who could perform the moves (which makes it all the more remarkable that she’s so good in the non-dancing moments, too). I think the less obvious—but just as likely and one that can live concurrently with the first—is that it’s one of a handful of sequences that justify cinema’s existence. The combination of dancing, acting, production design, cinematography (hello, Jack Cardiff), and editing is so stunning, it’s one of those scenes you could put on a highlight reel to explain why movies were invented in the first place (besides showing us workers leaving a factory and trains pulling into stations, of course)

It’s as close to perfect as I’ve seen in a movie and it kind of has to be for the movie to work, doesn’t it? If we didn’t have our breath taken away by what our central characters were struggling to create, it would seem almost comical. And yet, despite the beauty of the performance, The Red Shoes still hinges on this question: Was it worth it? Boris, Victoria, and Julian all give up a portion of their humanity—and, in the end, Victoria gives up her life—in service of their muse. Although maybe it’s no question at all. None of these characters have a choice. I hadn’t seen The Red Shoes in years before that recent screening, so some of the plot details and scenes had gotten a bit blurry. This time around, I was struck by the moment after Victoria and Julian had gotten married and in which Victoria can do nothing to hide her discontent. They clearly love each other but it’s not enough, particularly for Victoria, who’s never found the professional satisfaction she enjoyed working with Ballet Lermontov, however awkward things had gotten with Boris. Another movie ends with our two lovers finding each other and heading toward a happily ever after after leaving their tyrannical boss behind. The Red Shoes wants to know what happens after that moment, when they discover love isn’t enough.

Scott, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the ballet sequence. And I’m also going to anticipate a (correct) objection you’re likely to raise about that last paragraph. Is it fair to call Boris a tyrant? The film treats him with more complexity and sympathy than tyrants usually get. And yet he bears much of the blame for Victoria’s fate, doesn’t he?

Scott: An audience applauding mid-movie after a particular sequence? I feel like I’ve experienced that before, but the only example that’s coming to mind is the response to the long, long sex scene in Blue is the Warmest Color, which drew applause at Cannes en route to the Palme D’Or, only to have its reputation tarnished by Léa Seydoux’s criticism of director Abdellatif Kechiche and a not-so-generous assessment by actual lesbians. In any case, as I wrote before, I love the placement of the sequence about dead center in the movie, because we can see it as the culmination of a great collaboration and the peak from which these characters go tumbling down. While I don’t think The Red Shoes is pessimistic about the possibility of artists achieving a healthier work-life balance, there’s something to Lermontov’s argument that a dancer like Victoria can only reach the greatest heights by devoting herself wholly to her craft. Then again, that belief also reveals a corrosive obsession with Victoria that is more substantial than a mere disappointed aesthete. He wants to possess her, which isn’t a terribly collaborative word, is it?

But yes, let me dig into the dance sequence itself. I feel like this is one of my favorite axes to grind, but the movie musical has become a lost art and a film like The Red Shoes help clarify why. With rare exceptions like Steven Spielberg’s excellent revitalization of West Side Story, not enough thought is given toward valuing both the cohesive flow of dance choreography and making the camera itself an important partner in that choreography. Yet even the pleasures of watching Moira Shearer float across varied stage set-ups don’t quite encapsulate what’s really special about the sequence, which to me is how Powell and Pressburger liberate themselves from the theater and use techniques/effects that are unique to the cinema.

There are a lot of old-school in-camera effects—my favorite being Victoria slipping into the Red Shoes mid-air like something out of the 1940 The Thief of Bagdad, which Powell co-directed—and a combination of backdrops that make it seem as if time and space have collapsed around her. A swirling newspaper cut-out could never move around so magically on stage, much less morph seamlessly into a human partner, and you couldn’t have a busy carnival scene suddenly slip into an empty, abstract space where Victoria is floating through the air. Powell and Pressburger manage the seemingly impossible feat of persuading us of the true collaborative genius of this trio while also conjuring magic that could only be done for the movies. Maybe this suggests the level of creative energy Lermontov believes they could achieve together—or he could achieve with Victoria, most importantly—is a fantasy. But, you know, it’s also just an inspired feat of cinema.

There’s a degree to which Lermontov is simply full of beans, however. When he hears of Victoria and Julian’s relationship, he reacts like a spurned would-be lover, raging over what he perceives to be an “idiotic flirtation” during a performance in which Julian blows a kiss to Victoria from the orchestra pit and she smiles. Had he not known in advance about their coupling, he probably wouldn’t have noticed because it’s so imperceptible. He then professes to be unhappy with Julian’s latest composition (“childish, vulgar, insignificant”) and fires him when Julian talks about ballet as “a second-rate means for expression” for a composer of his ability. (That’s one of those things you say, I think, when you know you’re about to get fired anyway.)

But to answer your other question, no, I don’t think The Red Shoes dismisses Lermontov as a petty tyrant, though he’s capable of doing petty, tyrannical things. His devotion to his ballet company is unquestionably all-consuming and Victoria represents, to him, an opportunity to achieve his dreams in a way that wouldn’t have been possible for another dancer. When Victoria throws herself in front of the train, I feel like Powell and Pressburger register his grief most profoundly. You have that reserved yet heartbreaking announcement to the crowd waiting for her performances. (“Ms. Page is unable to dance tonight. Nor, indeed, any other night.”) And then the idea to honor her role by carrying on with the ballet with a spotlight where her body would be is a lovely gesture. Does he mourn the loss of Victoria the human being or Victoria the transcendent dancer? However you answer that question, his grief is real.

What do you think of the ending, Keith? And of the relationship between The Red Shoes as a fairy tale and this movie that’s been spun out of it? I also wonder what you make of the production overall. We might remember the dance sequence and all the soundstage marvels therein, but the film also takes advantage of real locations. That seems to be part of the narrative strategy, too.

Keith: Both The Red Shoes and The Ballet of the Red Shoes within it are only loosely inspired by the original Hans Christian Andersen story, a grisly parable about vanity and piety in which a girl’s insistence on wearing red shoes instead of black to church leads an old soldier to curse her to dance forever—and even to see her red shoe-clad feet bar her way to church after she has an executioner cut them off. (LIke I said, grisly.)

This might be a matter of Powell and Pressburger seeing a framework they liked and retrofitting it for the story they wanted to tell. But you can also see it as a work in conversation with the Andersen original. Victoria (and, allegorically, the character she plays on stage) ends up being overwhelmed by forces beyond her control, not because of a character flaw but out of an uncontrollable drive to create and perform. Where the unnamed “little girl, pretty and dainty” of Andersen’s story begins dancing for selfish reasons, Victoria does so in service to a muse that allows her to create beauty but at the cost of everything else. Yet Andersen’s protagonist, Victoria, and the heroine of the ballet all meet the same fate in the end. But where the fairy tale character repents her wicked self-regard and is taken to heaven, we never get that kind of reassurance with Victoria. It’s impossible to say that she’ll live on through her art, too. The moving final tribute is filled with a sense of what’s been lost, not what’s been created.

I think the Archers’ ending is less cruel, or at least more humane, than Andersen’s, which takes place in a suffocatingly pious moral universe in which God gets royally pissed at the smallest sleight. Victoria has a much more complex inner life than her fairy tale forebear and the film depicts her as an artist every bit the equal of Julian and Lemontov. But there’s also a kind of grim inevitability to her fate. Making an impossible choice proves, well, impossible. And if every moment leading up to her death didn’t convey that impossibility, the ending would play as a morality tale rather than a tragedy.

As for the use of real locations, that seems like an essential choice, too, providing a contrast between the artifice of the stage and the real world. If there’s a flaw to that scheme, it’s that the film makes the locations look just as beautiful and dreamlike as the world of the theater. Similarly, I appreciated the nods to the realities of show business, like the extremely modest theater where Lermontov sees Victoria dance purely for the sake of dancing and sees her talent in full. Art doesn’t need grand trappings to find greatness. (And seeing Victoria there seems akin to catching the White Stripes at a small club before everyone else knew who they were.)

Scott, I’m not sure I’ve fully unpacked the ending, or at least I’d love to hear more of your thoughts about it. Is Victoria’s fate particular to her or to anyone who tries to be an artist and live their lives? And, since we’re bidding adieu to the Archers (at least within this project) how do you see this fitting in with the rest of their filmography?

Scott: I didn’t come away with the impression that Victoria’s fate could be generalized to any degree. Do we really think the Archers are fully bought into Lermontov’s idea that artistic greatness requires a total commitment to the craft, without the distractions of love and other pursuits? Despite his seeming reserve, Lermontov’s emotions run extremely hot and his objection to Victoria and Julian’s relationship is as much about his need for control as his thwarted artistic vision. If anything, the tragedy of The Red Shoes is the reverse: Those red shoes force a dancer to wear them forever, which is a suffocating proposition for someone like Victoria, who leaps to her death because it’s her only chance to be liberated from this curse.

As for how this fits into the rest of the Archers’ filmography, The Red Shoes was the apotheosis of their collaboration and their partnership declined sharply afterwards, with a string of critical and financial failures, including an ugly attempt to make a movie with David O. Selznick (1950’s Gone to Earth a.k.a. The Wild Heart). They had thrived during the war and immediately afterwards, and I think The Red Shoes pairs particularly well with Black Narcissus in its use of color and its unreserved, florid passion. Perhaps our readers have some post-Red Shoes titles they wish to defend—The Tales of Hoffmann doesn’t count—but they were to the ‘40s what John Frankenheimer would be to the ‘60s: A decade of non-stop brilliance, followed by a rockier postscript. What’s your take on how this film fits into the Archers’ mission? And what’s next in our little project?

Keith: I have to admit that the later Archers’ work—not counting Peeping Tom—is unknown territory for me in part because of that reputation. It’s worth noting that, per Schoonmaker, their split was extremely friendly. They just wanted to go in different directions creatively but remained close throughout their lives (and occasionally collaborated again). I’m reluctant to impose an arc on their masterpiece run, but if we start it with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (and maybe we should start sooner), you can see a bit of a broadening of scope, though any run that starts with a film about nothing less than the changing notion of what it means to be English as it plays out across decades is already pretty wide. But they share common elements, including one suggested by the title of their 1945 film I Know Where I’m Going! Archer protagonists think they understand their world and their place within it only to be disabused of that faith, whether it’s Colonel Blimp coming to understand his time has come and gone or RAF pilot Peter Carter coming to a full understanding of life’s beauty at the moment of his death. (Or is it…?) Theirs is a world that has to be experienced to be understood. Sometimes those journeys of discovery lead to unexpected moments of happiness, sometimes to the realization that great beauty can demand a terrible reckoning.

Scott, we’re done with the Archers (at least as far as this project is concerned). Next up we’ll be discussing a film whose influence can’t be understated: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. We hope you’ll join us in three weeks.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

I saw this (on glorious 35mm!) at a revival theater back in the 80s. I'd never seen it, and tried to avoid knowing much about it going in. I was enchanted from the first frame, but when we got to the "Miss Page will not be dancing tonight" scene, I completely lost it. The writing is superb and the spotlight dance is heartbreaking, but it's really Anton Walbrook's performance that sells it. His performances in this and Colonel Blimp can't possibly be praised enough

FWIW Schoonmaker does not prefer you to watch these restored versions on 35mm, even though the BFI has created prints of them. Her reasoning is that these are one generation removed from the restoration work.