#95 (tie): ‘A Man Escaped’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Robert Bresson's minimalist prison break film suggests God's grace and guiding hand. It's also a nail-biter.

A Man Escaped (1956)

Dir. Robert Bresson

Ranking: #95 (tie)

Previous rankings: #69 (2012)

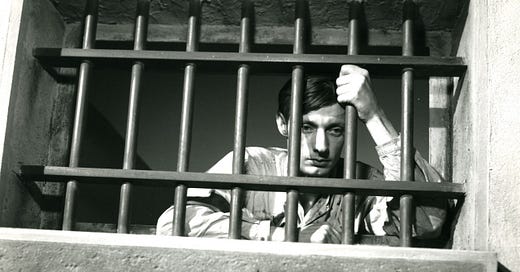

Premise: At Montluc prison in Lyon in 1943, Fontaine (François Leterrier), a member of the French Resistance, awaits a grim fate at the hands of the occupying Germans. Escape seems impossible, but he notices a weakness in the door to his solitary cell and, using the handle edge of a purloined spoon, starts methodically carving at the door and piecing together a route to freedom. As the days inch closer to his execution, Fontaine has to consider more serious risks, including whether or not to trust a new cellmate, François Jost (Charles Le Clainche), who could be a stool pigeon or more simply a hindrance too significant to gamble on.

Scott: A Man Escaped will be the first of two Bresson films we’ll cover in this feature—we’ll have to wait a bit until getting to the second, Au Hazard Balthazar, at #25—but Bresson’s become one of the truly dominant figures of the poll. In 2012, he had three in the Top 100 and six total in the Top 250, reflecting his unique stature within French and European cinema, and a stylistic asceticism that’s about as disciplined and pure as movies can get.

There’s a lot going on in a film like A Man Escaped, but you have to note from the start how much Bresson leaves out, the absence of superfluous detail in the storytelling and within the frame itself. The result, in my experience anyway, is enhanced concentration, a feeling that every moment is important, no matter how seemingly mundane. And it arises from a solitary man who needs to be efficient and deliberate in his actions, in order to mitigate risks that are already imposing, to say the least.

A Man Escaped was released a year after Jules Dassin’s quintessential heist film Rififi, which builds to that near-silent 45-minute robbery centerpiece, and I think the two films share a common philosophy. Suspense isn’t achieved through action, necessarily, but through the accumulation of mundane detail, the simple nuts and bolts of pulling off a job. Working from André Devigny’s memoir, Bresson has the audacity to open the film with a director’s note that it’s a true story and that “I present it as it happened, without adornment.” That’s an awfully high bar to set for yourself, given that adornments are precisely what we associate with movies based on true stories, which are inevitably too messy not to massage a little for the screen. But Bresson certainly convinces you that he’s done just that, and the narrowness of Fontaine’s goal here makes it possible. He wants to escape from Montluc before the Germans execute him. That commands his complete attention– and ours.

As with his previous film, Diary of a Country Priest, Bresson uses voiceover narration to give us direct access to his hero’s thinking, but it’s very rare that Fontaine’s thoughts could qualify as introspection. There’s a point late in the film when he has to consider the possibility of killing another man, but that’s as much a practical question as a moral one, since Fontaine’s survival is paramount from the start. Our introduction to Fontaine is a brilliant self-contained setpiece that establishes his combination of will and calculation, which surely served him well in the Resistance. He’s sitting in the back of a German car next to two men in handcuffs, all en route to Montluc, and he’s depressed the handle on the back door, looking for the right moment to push it open and tumble out to freedom. Bresson emphasizes Fontaine’s patience and his own, as certain opportunities for the car to stop come and go until it finally halts in front of a trolley and Fontaine attempts his getaway. That he’s nabbed immediately by Germans in the car behind him helps set the stakes for the prison break he’ll spend the rest of the film attempting. The implication is that even if he manages to slip out of his cell, he’s far from a free man.

How did you feel while watching this one, Keith? Because I honestly think it’s a suspense classic from stem to stern—and maybe the best place to start for anyone who’s new to Bresson. You’re acutely aware of the risks Fontaine is taking on, despite his strenuous efforts to mitigate them—efforts so strenuous, in fact, that the other inmates are executed before he finally follows through on his plans. Can Terry, the man in the courtyard below his cell, be trusted to send messages out to his family and to his superiors in the Resistance? Will the sound of him scraping away at the soft wood between the panels on his cell door be detected by people other than his neighbors? How can he prepare for obstacles that he cannot see but will need to work around? And these questions come before the even bigger problem of what to do about Jost, the young cellmate that’s introduced to him in the 11th hour. Has he met a comrade or a snitch?

Nail-biting stuff, right? What was your impression of A Man Escaped this time around, Keith? There are some political and spiritual components of the film that we’ll need to discuss, but this film is a banger, is it not?

Keith: A banger it is. I think the way Bresson’s work is talked about, including by Bresson himself, makes it sound unapproachable when it’s really not. This film is tense from start to finish and though Bresson may not have had much use for film genres or a need to please audiences, A Man Escaped works extremely well on that level. The reveal of the mysterious squeaking whir as a guard patrolling on bicycle is alone a master class in paying off mounting dread.

I’ve found all the Bresson films I’ve seen—and, admittedly, I still have to catch up with some of his later work, a lot of which has become hard to find these days—quite gripping. Bresson’s austerity strips away a lot of cinematic ornamentation, but what’s left is still recognizably a movie, whether it’s focused on a prisoner’s perilous escape attempt or an ailing priest’s spiritual crisis. (It’s also not entirely without adornment, to use Bresson’s word. I kind of chuckled to myself when that director’s note immediately gave way to the sound of Mozart on the soundtrack.)

That said, we should probably talk a little bit about what separates Bresson from other filmmakers. Bresson lays a lot of it out in his 1975 book Notes on Cinematography (which I haven’t read, but I did watch the very good 1984 documentary The Road to Bresson on the Criterion Channel, which does double duty as a Bresson primer and a portrait of the artist as a grumpy elder statesman). He refers to what he does not as “filmmaking” but as “cinematography” and eschews anything that makes film resemble theater. To that end, Bresson worked almost exclusively with non-professional actors, whom he regarded not as actors but “human models.” His reasoning was that human models’ performances were defined by “movement from the exterior to the interior” rather than actors, whose process is the reverse. This connects to his emphasis on close-ups of hands and feet and the repetition of daily routines, both of which are difficult or impossible to achieve on stage.

Again, that soundsforbidding, but A Man Escaped confirms the soundness of Bresson’s thinking. Leterrier’s performance as Fontaine is hollowed-out, making the character feel like a man reduced to survival instincts by his circumstances. His voiceover runs throughout the movie, but it’s of a piece with Bresson’s direction in its focus on action. Even when Fontaine breaks down and cries, the narration maintains a matter-of-fact tone in describing his state of mind. We mostly get to know Fontaine through watching him go about the business of being a prisoner while participating in an independent learning crash course on prison escape in his downtime.

Similarly, Fontaine can only assess the men around him by what he sees on the outside. Whether or not he believed actions reflected character before he wound up in prison, inside it’s become a matter of survival. The arrival of a cellmate, Jost, late in the film puts this to its severest test while ratcheting up the tension. A seemingly none-too-bright teenager who at worst is a plant sent to spy on Fontaine and at best wishy-washy about the Resistance, Jost could be a help or a hindrance to Fontaine’s plans, and if he determines he’s the latter, that means taking his life.

The underlying philosophy is existential, in some respects. We are what we do. The film has no interest in exploring the inner lives of Fontaine’s captors, perhaps, because their uniforms and their professions fully define who they are. But you’re right in noting that there’s a political and religious component to the film. In some ways, I think its politics are pretty simple. Fontaine is compelled to continue resisting even when escape seems impossible. But the film’s narrow focus on Fontaine’s efforts to escape, and his refusal to surrender to those who would prevent that escape, starts to take on a significance beyond survival.

Paul Schrader made Bresson central to his book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, which focuses on filmmakers who, Schrader argues, use the elements and actions of the material world to point toward the spiritual. Do you think Schrader is onto something? On the surface, A Man Escaped is a prison escape film reduced to its most basic components. What, beyond the tension it creates, makes it so resonant?

Scott: Keith, have you read the interview of Bresson that Paul Schrader did for Film Comment? There’s a PDF of it online here. The introduction alone is a kick: Schrader had written Transcendental Style in Film, and had clearly hoped to have his ideas validated by Bresson, but that most definitely did not happen. Bresson did not want the interview to run at all, and only relented much later at his producer’s behest. (A fun fact: Schrader conducted the interview before heading to Cannes, where a little film he wrote called Taxi Driver was premiering.) Schrader commits the common interviewer sin of asking the subject to affirm his thinking rather than ask questions; Bresson does not validate Schrader’s assertions, which of course doesn’t mean they’re incorrect.

But the interview does give some basic insight into Schrader’s religious reading of A Man Escaped. In his view, Fontaine’s decision not to kill Jost is what makes the film about grace and redemption. “We must choose grace as it appears to us,” says Schrader, “and, therefore, we will escape, even though we are predestined to escape.” The Tony Pipolo essay on the Criterion disc notes that Bresson’s original title for the film was Aide-toi, a way of saying “Heaven helps those who help themselves,” and Pipolo goes on to argue that Fontaine’s actions reflect a pragmatist’s form of faith. One of his more persuasive examples is a scene where Fontaine taps on the walls of a neighbor’s cell, disrupting a possible suicide attempt, and making him among the prisoners he inspires with his faith.

I do wonder, however, how much of a religious reading A Man Escaped would have gotten were it not for the context of two of Bresson’s previous three films, Diary of a Country Priest and Angels of Sin. Then again, the film’s subtitle, “The wind blows where it wants,” a reference to John 3:8, suggests that the Spirit operates in ways that are not easy to understand or predict, but nonetheless has a presence and a plan. This could apply to the war itself, which led many to crises of faith that surely wouldn’t ease at a prison where inmates can expect to be executed by their German captors. But it also offers some measure of faith that Fontaine has a benevolent overseer in his mission, and that he might trust that the variables in his plan will be resolved in his favor.

And there are so many variables! He has to trust that his scraping won’t be heard; that his materials won’t be discovered (including a pencil that would be grounds for execution); that none of the other inmates will rat on him; that his improvised hooks and ropes will hold; that Jost will not be a stool pigeon or an albatross; and that they won’t be detected by the guards on patrol. Bresson makes it clear at several points that no matter how much the scrupulousness of Fontaine’s planning mitigates risk, he’s facing extremely long odds on the escape. He can credit a “guiding hand” for that.

Or, as enjoyers of suspenseful prison break movies—like, say, The Great Escape seven years later—we accept the unlikelihood as a feature of the genre. What prison breaks haven’t seemed impossible? Moreover, the film could be understood simply as a tribute to the indefatigable courage of Resistance members, who are constitutionally incapable of conceding to the Germans. (Fontaine, in his narration, scoffs at the mutual understanding that the promise he was forced to make that he wouldn’t try to escape again would not actually be honored.) There is one memorable shot in the film that suggested the divine to me, however: a low angle of Fontaine in his cell with light streaming through the outside bars to his cell above. It could be a painting.

How about you, Keith? Is a religious reading of this film as obvious as perhaps it should be to me? Are there some other clues about what Bresson is up to? And are there any other moments that really stood out to you?

Keith: I think you’re right about the context inviting that reading, which might not be an obvious way to look at the film without it. But context matters and, beyond those early features, you have to consider the rest of Bresson’s work, which was concerned with moral, if not always explicitly spiritual, matters. But even removed from that larger context, the details of that final shot suggests this is about escaping more than just a prison cell: the mist that envelops Fontaine and Jost, the swelling Mozart music (again), and the sense of peace that settles over the film.

It might also be a matter of a film that’s so conceptually simple inviting viewers to read into it. This is going to seem like an odd digression, but bear with me: over the weekend, not long after watching A Man Escaped, I took my daughter to a screening of Cast Away, which is part of a larger retrospective of Robert Zemeckis films currently playing at the Music Box here in Chicago. In most respects, Zemeckis is a much different filmmaker than Bresson, but I couldn’t help thinking about A Man Escaped a lot during the scenes on the island that make up the heart of Cast Away. Like Fontaine, Chuck (Tom Hanks) has to use the meager resources at his disposal to overcome the odds to survive. And, like Bresson, Zemeckis puts the emphasis on the repetitive day-to-day tasks the protagonist has to perform in order to stay alive.

Again, Zemeckis’ style isn’t particularly Bressonian, but there’s certainly a lot less to strip away from Cast Away to get to Bressonian simplicity than in most big Hollywood movies. (The absence of a score during this stretch gives it an unusual starkness, too.) Beyond that, both films invite viewers to use these characters’ dire situations to reflect on some fundamental questions about what it means to be alive and to keep living. For both Chuck and Fontaine, the alternative is death and despair. It’s not that they do what they do because they have no other choice. They do: they can give up. But both are films about what it means not to give up and that necessarily invites philosophical and spiritual readings. Or, as Bresson put it in that Schrader interview “[T]he more life is what it is—ordinary, simple—without pronouncing the word ‘God,’ the more I see the presence of God in that.” (And, of course, Bresson made films about characters who do give into despair, but the point still stands.)

So, in conclusion: Bresson made bangers that anticipate the work of his spiritual heir, Robert Zemeckis, is that what we’re saying? Wait, that’s a horrible takeaway. My main thoughts on revisiting A Man Escaped is how powerful Bresson is as an idea, his films serving as a model of simplicity that other directors aspire to reach. (The influence on Schrader is stronger now than ever.) But that wouldn’t matter if A Man Escaped, for starters, didn't work just as well as a film. It’s an immediately stirring film that invites reflection after the fact.

We’ve got more Bresson ahead of us via a date with a soulful donkey. Any last thoughts on this one?

Scott: Bresson walked so that Zemeckis could run, right?

My main thought, beyond a conviction that A Man Escaped is more conventionally thrilling than Bresson’s austere reputation might lead you to believe, is how much seemingly mundane details matter when you separate the truly great filmmakers from the pack. The effect of Bresson stripping away superfluous elements is a heightened attention to the things that matter. He’s directing your eyes—and sometimes your ears—to precisely what he wants you to notice. That’s the advantage black-and-white films have had over color, and here the overall effect is to pick up on specific details, like the worrisome crunch of gravel underneath Fontaine and Jost’s feet as they make their escape or the labor of braiding horse-hair pillow stuffing into a makeshift rope. It’s always the mark of a great heist or break-out movie when you’re left feeling like you’d stand a chance of doing it yourself.

Another thought is that A Man Escaped would pair well with Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1969 classic Army of Shadows as a tribute to the bravery of Resistance members. There’s no religious component to the Melville film that I can recall, but who can forget that early scene where our hero goes to the barber and doesn’t know if the razor blade against his throat will trim his neck or slash it open? That’s the sort of faith that drives Fontaine forward, which may have something to do with the Spirit, but we’re acutely aware, at all times, that he’s putting his life on the line. And Bresson makes you feel the losses of the men like Terry who took those risks alongside Fontaine but would never know freedom. Bresson staying in Fontaine’s cell as the machine gun fire pops in the distance underlines his helplessness in their fates.

One last thing: The use of voiceover narration is unique here. We hear Fontaine’s voice constantly as he relays his thinking to us, but there’s barely a moment of introspection. This isn’t Schrader’s Taxi Driver, which provides a diaristic window into the mind of a sociopath, but a detailed accounting of how Fontaine goes about the practical business of breaking out. It’s what allows Bresson the freedom to focus on Fontaine’s hands as he scrapes at the wood with his spoon, because the narration has taken care of the “why” part. He cannot reflect on the horrors he’s seen or the fear of what might happen to him. The basic quest for survival disciplines his mind.

We’re finally through the logjam at #95, Keith. Now we enter a new logjam, with Parasite, Yi Yi, Ugetsu, The Leopard and The Earrings of Madame de… all knotted up at #90. Some pretty incredible viewing ahead for us.

Next: Yi Yi.

Previous entries:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

A Man Escaped is the absolute best defense of cinematic minimalism *because it has an inherently interesting subject.* It's a story that works completely without adornment, because the nuts and bolts of a prison break are fascinating. I loved it, went to check out more Bresson...and yeah, none of it is riveting like this. But I'll always have this one

A Man Escaped was the first Bresson I watched - shown in my first college film class decades ago. It’s been a favorite since then, and I was pleased to see it still on the Site & Sound list.

Thank you for this series of articles - I’m looking forward to reading your thoughts on the current version of the list. The last few months I’ve being doing some catching up with films on the list I haven’t seen. So far I’ve watched Black Girl, Tropical Malady, Once Upon a Time in the West, and I’m currently in the middle of The Leopard. The Leopard is interesting - before I watched I had it pegged as one of my least favorite kinds of movies, and I didn’t enjoy the first third much. But once Alain Delon’s Tancredi met Angelica, and the Prince’s plan started to unfold, it became a lot more interesting for me.