#78 (tie): 'Histoire(s) du Cinéma': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Jean-Luc Godard's colossal experimental essay covers a century of movies (and music and painting and politics) in typically iconoclastic fashion.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Histoire(s) Du Cinéma (1998)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

Ranking: #78 (tie)

Previous rankings: #48 (2012).

Premise: A sprawling, eight-part video essay made between 1988 and 1998, Godard’s longest film uses then-emerging video editing techniques to construct a personal and characteristically demanding history of film. United loosely by theme, each installment (which Godard divides into four chapters distinguished by the letters “a” and “b”) moves freely through aspects of film, history, painting and music. Footage from throughout film history, images from the news, Godard’s narration, the clips’ soundtrack, other voices, score music, songs, and title cards overlap and blur into one another as the director circles back to a few thematic phrases such as “Fatale beauté,” “Seul le cinéma,” and “Une Vague Nouvelle” that double as chapter titles (but recur across different chapters).

A further bit of clarification: Sight & Sound lists this as a 1988 film. Godard finished the first two parts in 1988 and the film played as a work in progress over the following years but was not completed until 1998. We are discussing the work in its entirety.

Keith: I did not learn the history of cinema watching this. Zero stars.

I kid, of course, but Histoire(s) du Cinéma offers an even less straightforward history lesson than you might expect from Godard. The title doubles as a warning. It can be read as “The History of Cinema” or “The Story of Cinema” or either version’s plural. The suggestion that there is no single history of cinema also acknowledges that this is very much one person’s version of that story / those stories. (That kind of wordplay reads more eloquently in French, doesn’t it?)

This is a difficult work, to say the least. I found myself by turns enchanted, bored, frustrated, and moved by what Godard was doing, sometimes in rapid succession. It’s easy to dismiss, too, if you’re so inclined. At one point, Chaplin’s image fades into Hitler. Flashes of hardcore pornography appear side by side with images of Hollywood sensuality. Godard’s observations, delivered in a doomy intonation, are often gnomic. It can be at once obscure and obvious. But lock into its wavelength and there’s really nothing else like it. Whether that’s for better or worse is a matter of taste. And if your reaction to this film is like mine, it can reverse course several times in the course of watching it.

This is advanced-studies Godard to the point where an outside voice can put it into perspective better than I can. In “Trailer for Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma” a 1997 piece that’s half analysis, half interview with Godard, Jonathan Rosenbaum draws extensive comparisons between Histoire(s) and James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. Joyce’s final work, that book is a flood of wordplay, references, and Joycean neologisms that only occasionally takes the form of what might be called a narrative. Rosenbaum writes:

“[J]ust as Finnegans Wake figuratively situates itself at some theoretical stage after the end of the English language as we know it — from a vantage point where, inside Joyce’s richly multilingual, pun-filled babble, one can look back at the 20th century and ask oneself, “What was the English language? ”– Godard’s babbling magnum opus similarly projects itself into the future in order to ask, “What was cinema?”

[...]

“As “unwatchable” and “unlistenable” in many respects as Finnegans Wake is “unreadable,” Histoire(s) du Cinéma remains difficult if one insists on reading it as a linear argument rather than as densely textured poetry; in my experience, it is most rewarding when approached in a spirit of play and innocence.”

I think this is an excellent comparison but, for me at least, not entirely in ways that make me warm to the film. Ulysses is my favorite book, one I’ve read and revisited often over the years. I find something new each time and my perspective on the novel changes as I get older. (I was recently shaken to realize I’m now considerably older than Leopold Bloom.) But I’ve never been able to do more than dip my toes into Finnegan’s Wake. And that’s almost certainly an indication of my limitations rather than Joyce’s fault. But, similarly, I kept thinking of all the Godard films I could have watched over the course of Histoire(s) five-and-a-half-hour running time that might have meant more to me.

Scott, some consider this to be Godard’s magnum opus. They might be right. It’s stunningly ambitious and innovative in its use of video editing, which allowed for a freer kind of montage than film editing in these pre-digital years. (In that same Rosenbaum piece, Godard says “video is closer to painting or to music. You work with your hands like a musician with an instrument, and you play it.”) I’d love to start with your first impressions of the film. What do you think Godard is doing and to what degree did you find it successful?

Scott: This is going to be a long-winded answer to your question, but after binge-watching Godard’s 266-minute experimental film, I feel entitled to my discursiveness. One thing I think about often, as the father of two girls, 12 and 15, is how dramatically different their upbringing was from mine, specifically the fact that they’ve been using the internet their entire lives while I didn’t start on a dial-up modem until my mid-to-late 20s. When older adults complain about “kids these days,” I get reflexively defensive about it, because it’s my firmly held view that adults now have absolutely no conception of how different childhood and adolescence is now than when they grew up. Family life, peer relationships, the unique stressors of an age of social media and mass-shooting lockdown drills— nothing is the same, and I think it can be hard, when you’re living in the moment, to realize how much the ground has shifted under their feet (and under ours). How do you even start to get perspective on that? And even if you tried, how could it not be a perspective that’s limited and personal?

That’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma to me. Here’s Jean-Luc Godard, who has forgotten more about movies than virtually everyone on earth could ever know, standing near the end of a century of movies and giving his impression of what it all means. We may have grown up with cinema, just as Godard did, but it’s still a very young medium and perhaps analogous to the internet in how transformative it has been in society. For all of human history leading up to the 20th century, we did not have the tools to see our lives (and fantasies and electric typewriters) reflected on screen at 24 frames-per-second. This form that we take for granted as a source of art and entertainment, of memory, of essential truths (and deceptive fictions), and of commercial and personal expression did not exist. And so of course the trajectory of 20th and 21st century lives has been altered by it in ways not even Godard can begin to wrangle.

But the scope of his experiment does suggest that Godard respects the profundity of his chosen medium, in all its beauty and terror. As you say, Histoire(s) is a difficult watch to put it mildly. Even by the standards of later Godard experiments that got some festival play—2001’s In Praise of Love and 2010’s Film Socialisme, which I did see, 2004’s Notre Musique and 2014’s Goodbye to Language, which I know only by reputation—this is a steep hill to climb, even if it breaks up into more digestible chapters. Godard was playing with emerging video techniques and those figure into an overall montage that’s extremely dense with superimposed and manipulated images and clips, music samples, bits of philosophy and literary excerpts, and a lot of jarring juxtapositions. I will take everyone’s word that it could be likened to Finnegan’s Wake, another work I know only by reputation, but that’s a kind way of saying that it’s frequently illegible, connecting with me only in fits and starts.

Then again, it has a mesmerizing rhythm to it that reminds you that you’re in the hands of an intuitively brilliant filmmaker. Certain recurring elements, like the staccato clacking of that typewriter (which ends in the second half of episodes) and the repetition of key ideas, have the effect of drawing you into a space where you can consider your own relationship to cinema at the same time Godard does. Looking at my notes from the second episode, for example, one repeated statement (“Cinema was projected and the men saw the world was there. An almost trouble-free world, still. But a telling world.”) leads into images of sex and death with a soundtrack that goes from a Leonard Cohen song to Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho. It’s a challenge to parse out what Godard is saying here, but all of those elements are evocative prompts for viewers to think about their relationship to them.

I have my thoughts on what certain moments in Histoire(s) mean to me, but I’m curious to know what you thought about the overall scope of the project. While there’s impressive continuity across the whole thing, given that it took a decade to finish, did you also feel like the last four episodes were a notable shift from the first four? They seemed less jagged to me and more cohesive—if that’s the word—in their overall montage. I can’t say they get easier to understand, exactly, but they have a nicer flow to them. Am I wrong about that?

Keith: I mean, the scope is the whole of cinematic history and beyond. How can you not be impressed? And I think Godard’s strong sensibility and personality contributes quite a bit to the consistency. That said, I think you’re right about the home stretch having (a bit) more focus than the opening chapters. There’s more of an attempt to focus, if fuzzily, on Hitchcock or Italian films, but always in relation to Godard’s particular version of film history/histories/story of film/stories of film. Zero shots, if I recall correctly, of a shirtless Godard putting his head in the frame of a television.

That story plays like a love letter laced with mixed feelings, and the work of someone trying to figure out what it all meant before bidding it farewell. That Godard lived for many years after this and worked up until the end of his life doesn’t really change that feeling. Its length and obscurity exhausted me, but I can’t imagine it taking any other form, you know? A shorter, clearer version of Histoire(s) is hard to imagine.

Here’s my favorite passage, which appears twice over the course of the film in different contexts. It’s Godard reflecting on the birth of photography and, consequently, cinema:

“Photography could have been invented in color. Colors existed, but here’s the thing: On the eve of the 20th century technology decided to reproduce life. So we invented photography. But since morals were still strong, and we would take everything from life, even its identity, we mourned this killing. And it’s with the mourning colors, black and white, photography was born.”

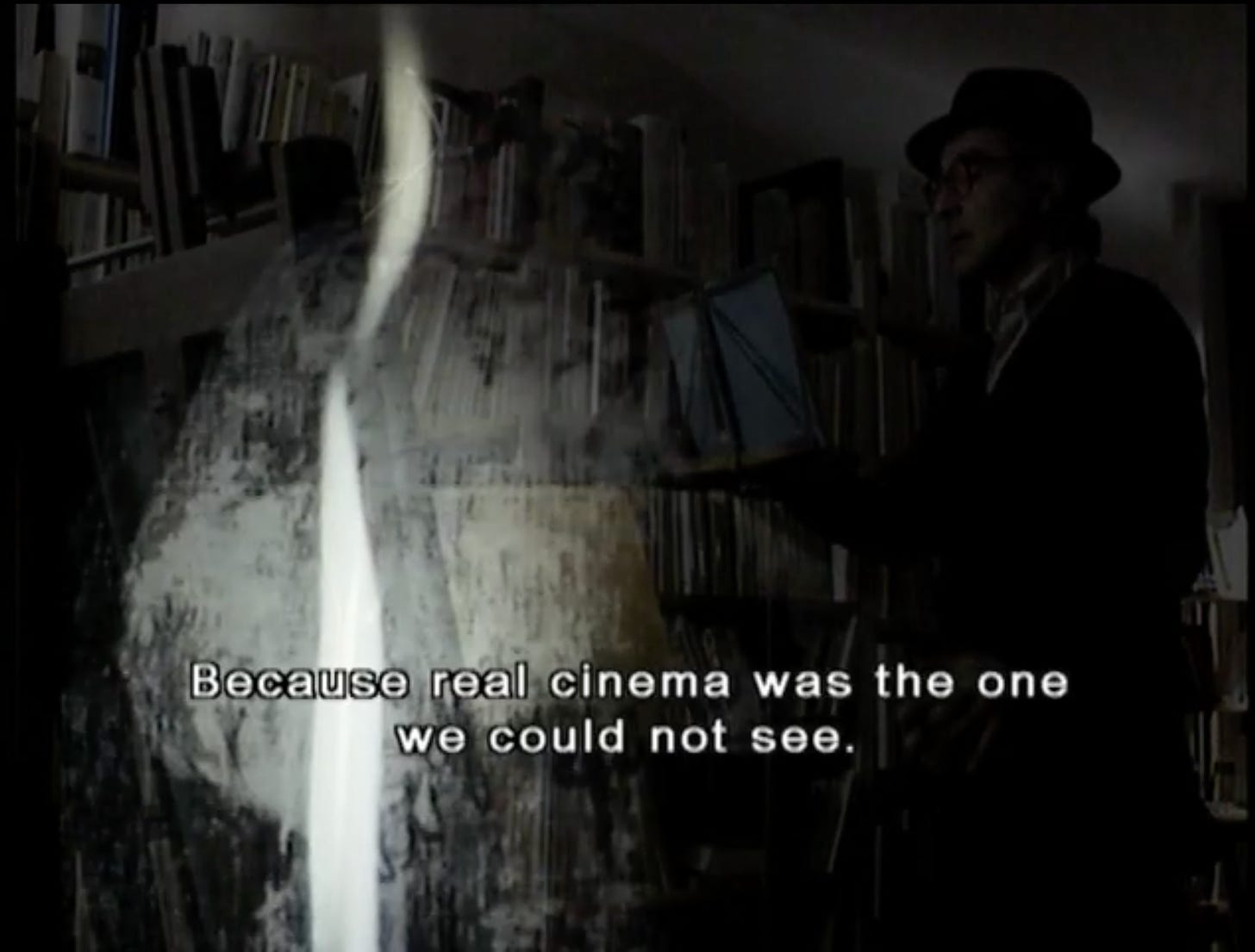

As history it’s shaky, to say the least. But in its depiction of the introduction of the photograph as a kind of Promethean gift destined to rob humanity of its innocence, whatever its pleasures and cultural contributions, it’s sad and beautiful. So are Godard’s reflection on his own contributions, and those of other members of the French New Wave who, in his telling, tried to realize dreams stirred by the movies in which they immersed themselves, “Because real cinema was the one we could not see.” Both are moments that speak to what you referenced above, the newness of cinema to his generation.

I also think, like Werner Herzog these days, Godard understands the persona he’s created for himself over the decades and is fine playing into it, sometimes humorously, as in his dismissal of British cinema, but more often in the freedom he gives himself to make sweeping statements that don’t worry too much about sounding hyperbolic. Not that Histoire(s) doesn’t seem sincere, but it also plays like the work of someone who understands what the world expects him to be: lyrical, probing, provocative, and cryptic.

But oh did Histoire(s) wear me out. I genuinely love the sections mentioned above, and a later section on Hitchcock that credits him with achieving what Alexander and other conquerors could only dream of accomplishing: control of the universe. But these feel like footholds of understanding in a river of confusion. When one chapter ended with a reference to Emily Dickinson, I had to chuckle. What? Why? I’m sure there’s a reason I just don’t grasp, but I have no idea what it might be.

Scott, was that similar to your experience? I’d like to hear what moments worked for you (and which didn’t). And, perhaps this is a question the film wants me to ask, but were you made a bit queasy by the use of Holocaust footage and footage of other war atrocities amidst all the other imagery, mostly from narrative films? In a posthumous assessment of Godard’s relationship with the Jewish community for The Times of Israel, our former Dissolve colleague Andrew Lapin delicately navigates a thorny issue that’s too big to get into here. But it’s worth noting that Godard and Shoah filmmaker Claude Lanzmann would disagree about the use of archival imagery in telling the story of the Holocaust. Lanzmann avoided it. Godard felt it necessary. Whichever was right, I still find myself feeling like its placement here and that of other real-life images of death are trivialized in this context, even in a work of high seriousness. It can be partly explained by Godard’s objections to Spielberg and Schindler’s List, which he viewed—I believe this is accurate—as a kind of Hollywood colonization of history. What’s your take on that?

Scott: Boy, you’re really putting me in a comfortable spot here! As a general rule, I tend to give a pretty broad latitude to filmmakers when it comes to what is permissible imagery, so I’d side with Godard over Lanzmann, though obviously all of this is context-dependent. Spielberg was a favorite target of Godard, who dings him a bit in Part Five on Histoire(s) and would criticize him more heavily for Schindler’s List in In Praise of Love, in which it’s noted that Mrs. Schindler was never paid and lives in poverty in Argentina.

Anyway, to answer your question, I did not find the archival imagery in Histoire(s) to be used cavalierly or irresponsibly, because Godard is committed to wrestling with the relationship between cinema and history, and how one informs the other. In the 20th century, the camera bore witness to the great atrocity of the Holocaust and confronting those images seems almost unavoidable for a project like this.

You also get some fascinating cause-and-effect relationships from the cinema/history mash-up, like when Godard talks about how “Friedrich Murnau and Karl Freund “invented the Nuremberg lighting when Hitler couldn’t even afford a beer at a Munich café.” Godard wants us to understand the awesome power filmed images can have and have had in shaping—and, through propaganda, diabolically manipulating—mass perception about the world. This quote about Murnau and Freund comes from the same episode (Part 4: “Deadly Beauty”) that arrives at that quote that you love about the difference between color and black-and-white photography. (“Technicolor films as vibrant as funeral wreaths” is one evocative line, too.) One of the things I love about Histoire(s) is just how Godard’s mind works. In that episode, he pulls images of Molly Ringwald, a music same from Tom Waits, and has a sequence that connects Joan Fontaine and the glass of milk in Hitchcock’s Spellbound, the art of Eugène Delacroix and Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. What does it all mean? I don’t know, but don’t such associations reflect how the minds of many cinephiles work?

You mention this a little bit above, Keith, but I was fascinated by Godard’s assessment of cinema around World War II. It starts with him wondering why there wasn't a resistance cinema in 1944-45. He then goes on to praise the Italians, notably Rome, Open City (though there’s a shot of Germany Year Zero in there, I think) for confronting the pain and wreckage the war had wrought. This leads to the very cutting line you mention, when Godard says, “The British did what they always did in cinema: Nothing,” and some additional business about America making “advertisement movies,” the Germans having “no cinema” any more and a nod to the Poles with Kanal. How countries confront (and shrink) from wars while they’re happening and in their aftermath is an obsession of mine, because it’s such a test of artistic courage (and commercial will) and a test that’s so often failed.

I’m not even going to scratch the surface of a soundtrack that samples from Bach, Bernard Herrmann, Otis Redding, and Leonard Cohen—other than to say I dug the rights-testing range and eclecticism—but I was most compelled by Godard’s juxtaposition of film samples, even when I couldn’t necessarily track how, say, Jerry Lewis was connected to Anna Karina was connected to Renée Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc. Why is footage of hardcore sex superimposed with images from Hitchcock’s Vertigo? I guess they’re erotically charged in suggestive and not-so-suggestive ways. Is Godard taking a shot at François Truffaut when he follows up shots from The 400 Blows and The Wild Child with the line, “French cinema is dying under fake legends”? Seems like it, but it’s hard to track. Earlier in the series, Godard goes on a reverie in which Truffaut is mentioned in the same breath as Edgar Ulmer, so who knows?

The whole opus ends with a quote, credited to Borges, that’s quite lovely: “If a man walked through paradise in dreams and received a flower as a sign of his visit and found the flower in his hand when he woke up, what can we say? I was this man.” I’m reminded a bit of my favorite Joni Mitchell song, “The Last Time I Saw Richard,” which is the final track on Blue. The song recalls a visit with Richard late at night, a man disillusioned about love, believing that “all romantics meet the same fate some day, cynical and drunk and boring someone in some dark café.” But as our narrator points out to him, the quarter he keeps pumping in the Wurlitzer tells another story, “You’ve got tombs in your eyes,” she says, “but the songs you punched are dreaming.” That’s Godard and Histoire(s) in a nutshell. He is a cynic by nature, often harsh in his assessment of where film has taken us as a culture. But damned if those clips he’s punched ain’t dreaming.

Keith: That seems as good a place to end as any. This may be the most obscure film on the Sight & Sound list, so it might be worth noting why. The length partly explains it, but rights issues seem to be the real reason. And I think for a while, it was only available in mono? Chicago’s recently shuttered, and missed, DVD label Olive Films put out a full version in 2012 that remains the best way to watch Histoire(s). It’s still in print, but the film can also be found at the Internet Archive. There’s also a CD box set for anyone who wants to experience it purely as a sound collage (proficiency in French recommended)). And, however mixed my experience, I’m glad I watched this. It’s one of a kind and I would definitely recommend it to anyone made curious by this discussion. Scott, do you concur? And what’s next for us?

Scott: Worthwhile for sure, though it’s certainly not the best starter Godard. (Honestly, it’s probably the best ender Godard.) You simply have to get up to speed first by watching all of Godard’s other major work and absorbing all the important 20th century developments in movies, music, painting and history. All joking aside, I think the best way to approach Histoire(s) is with curiosity and humility, recognizing that you’re not always going to be on Godard’s wavelength but you can try to stay engaged. We have some other heavy lifts coming up for the Sight & Sound project, but the movie gods (and polling data) have been merciful for the next one, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death. (The streaming powers-that-be are thwarting us on this one, though. It’s on Criterion, but not on the Criterion Channel or any other major service.)

Next: A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

Keith, have you ever done a piece on Ulysses? If anyone could persuade me to give it another look, it would be you or Scott. I love art that is challenging, but this particular work felt like more of a chore than a pleasure for me when I finally dove into (and then stopped) reading it a few months ago.

Thank you! A terrific essay. Looking forward to more.