#88 (tie): 'The Shining': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

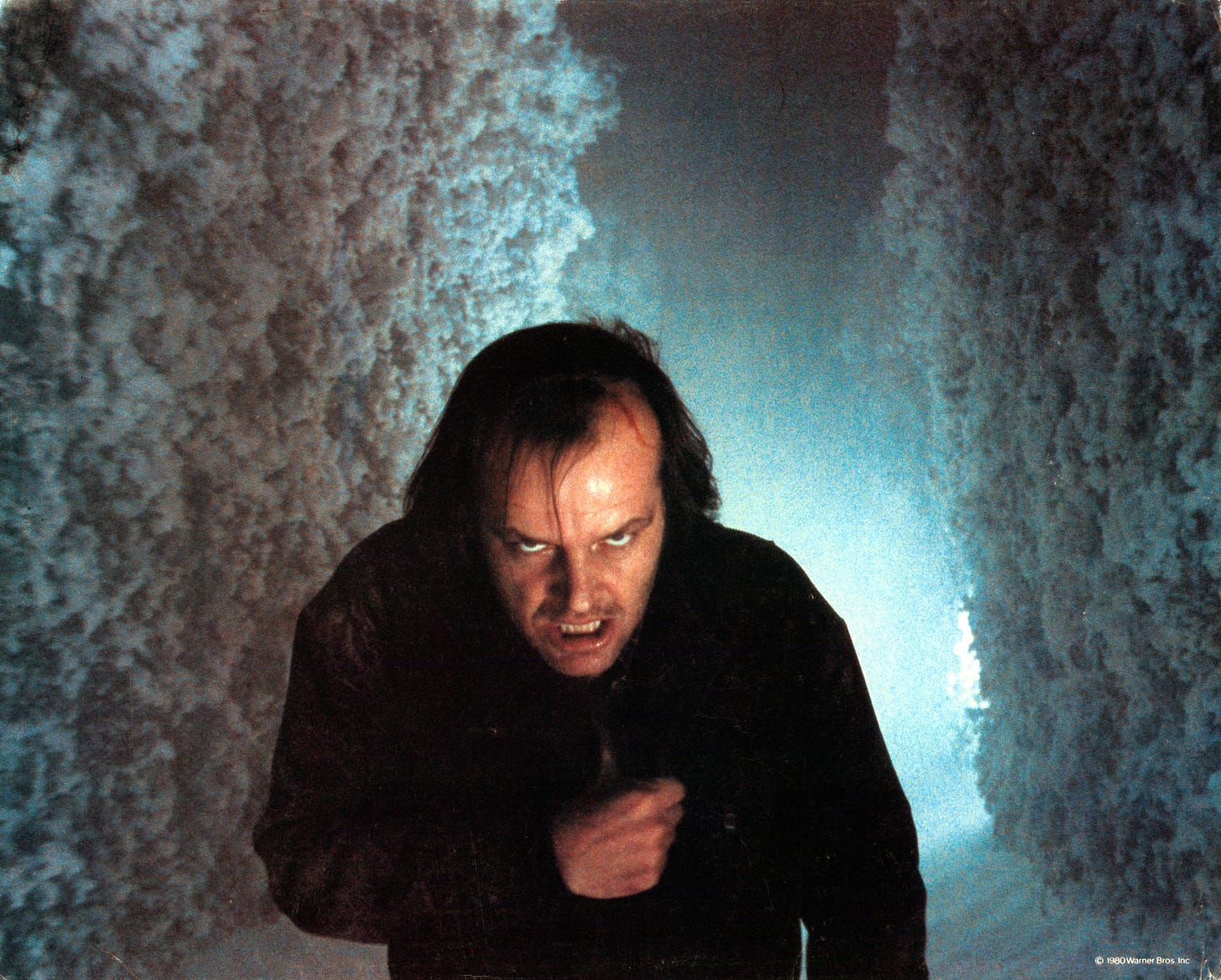

Stanley Kubrick's Stephen King adaptation turns a haunted hotel into the stage for a frustrated writer's family-endangering meltdown.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

The Shining

Dir. Stanley Kubrick

Ranking: #88 (tie)

Previous rankings: #123 (2012)

Premise: Former schoolteacher Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) takes a winter caretaker position at the Overlook Hotel, a luxurious and historically colorful destination so high up in the Rocky Mountains that it’s inaccessible for nearly half the year. For the next five months, Jack will live in total isolation with his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and his son Danny (Danny Lloyd), who has been having disturbing premonitions about the Overlook. Though his employers warn him about a previous caretaker, Charles Grady, who killed his family and himself years earlier, Jack assures them that he welcomes the time to work on a book and that his family will love it. But it isn’t long before Danny’s telepathic visions—which he shares with the head chef, Dick Hallorann (Scatman Crothers), who calls it the “shining”—start to manifest themselves in shocking fashion. The Overlook takes hold of Jack, who grows moodier and more menacing as the history of the place seeps into his conscience. With nowhere to run in the snowbound setting, Wendy and Danny scramble desperately to stay alive.

Scott: And now we get to Stanley Kubrick, with the first of three films in the Top 100, leaving Barry Lyndon and 2001: A Space Odyssey still to come. (He has two more deep in the Top 250, with A Clockwork Orange at #243 and Dr. Strangelove at #196.) We should say upfront that The Shining and Barry Lyndon, based on their critical reception at the time, were not exactly destined for glory. And that would fit into a broader pattern of regard for Kubrick’s work in general: They take a while to get their proper due, to the point where I can remember rolling my eyes at some of the pans that greeted his final film, Eyes Wide Shut, when it came out in 1999, my first year as a full-time, salaried critic for The A.V. Club. (In fact, Eyes Wide Shut was my first screening in Chicago, surrounded by luminaries like Jonathan Rosenbaum, Roger Ebert and Michael Wilmington. How about that for an exciting start?) It was a little like, “Are we really doing this again? Can we at least try to give Kubrick the benefit of the doubt here?”

To me, The Shining is self-evidently extraordinary from the very first sequence, which turns a Rocky Mountain pass into a landscape of eerie, uncanny, unsettling beauty. Between the music and elevated camera angles, which are so controlled it’s as if Kubrick has somehow mounted a helicopter on a dolly, you’re immediately set off balance. That becomes the prevailing strategy of the film itself, which perhaps flummoxed critics because it doesn’t behave like any other horror movie—just as Full Metal Jacket doesn’t behave like a typical war movie or Eyes Wide Shut a typical marital drama. Kubrick is reinventing the language from the start, softening up the audience through a pervasive sense of disorientation. In the beginning, we’re following Jack Torrance on his way to the job interview at the Overlook. But later on, when he’s bringing the family up for their five-month stay, Kubrick has them driving in a different direction: From left to right on the screen instead of from right to left. He does this constantly in the film, which is set up as its own giant hedge maze.

Kubrick takes his time establishing the Overlook’s history and Jack’s own uneasy relationship with his family, particularly an incident of domestic violence that led to him dislocating Danny’s shoulder. Wendy downplays the incident to Danny’s pediatrician, claiming it was more of an accident and insisting that Jack hasn’t had a drink in five months. But it’s an awfully tenuous grip that Jack has on his sobriety and Nicholson’s performance, from his first meeting with the Overlook’s administrators, has an edge to it that suggests he won’t keep it together for long. One of the persistent early criticisms of The Shining is that Nicholson’s descent into madness is more of a bunny hill than a larger slope, and Kubrick robs us of that progression. But I like how obviously unfit he appears for this situation, and how at home the Overlook feels to him as it nurses the darkness in his soul.

Truth be told, it took some time for The Shining to get its hooks into me, though I now regard it as one of Kubrick’s greatest achievements and welcome its climb up the list. In my defense—and maybe in defense of those who didn’t embrace at the time— the film is a real shapeshifter. I can think of few films that feel like different experiences every time you watch it. Not only do you notice new things you may not have grasped before, but you find alternative angles into it. Maybe those angles are not as extreme as the theories presented in Room 237, Rodney Ascher’s terrific documentary about the interpretations of various obsessives, but you don’t have to believe Kubrick is apologizing for staging the moon landing to have a fresh take on The Shining.

So what about you, Keith? Do you have a grand theory on what The Shining is about? And has this film shifted around for you a little, too?

Keith: It’s shifted and shifted again. Like a few other Kubrick films, I’ve found my view of this movie ping-ponging over the years. When I first saw it as an early teenager gorging on horror films, I thought it was spooky as hell but didn’t immediately grasp what set it apart. When I started to get deeper into movies, it was one I wrestled with the way you sometimes wrestle with movies you liked when you were younger. I found myself asking if it was really about anything or if it was just a lot of impressive technique. That feeling didn’t last long, though, and I’d come around even before I had a chance to see it in a theater for the first time about a decade ago, which cemented it as a masterpiece for me.

I think you’re onto something about each viewing revealing something new and this may be the first time I appreciated just how funny the movie is. It’s primarily a journey from the unsettling to the terrifying, but change the angle a bit and it’s an almost Strangelove-like string of scenes from a terrible marriage, with Jack serving as a kind of Jack D. Ripper figure and Wendy in the Lionel Mandrake role, trying to avert destruction by keeping him calm and pretending he’s rational no matter how bizarre his behavior. (OK, any comedy here is pretty dark, admittedly.)

From the first shot of Jack driving his family up to the Overlook, it’s clear that he hates them. Or, if not hates them, at least resents them. In his mind, they’ve become the obstacle standing in the way of his brilliant literary career. It’s also pretty obvious that he’s an alcoholic who’s trying to will himself out of his addiction without anyone else’s help. In the Overlook, he sees a solution to both problems: time and space to write in a place with no booze while his family does whatever it is they’re going to do as long as they don’t bother him.

Since rewatching the film, I’ve been revisiting Stephen King’s novel and it’s not hard to see why he doesn’t like this film. The plot’s basically the same but Jack’s quite different and the novel works best as the tragic story of one man’s inability to escape his demons, a tragedy catalyzed by a haunted hotel. In short, King’s core complaint is pretty close to the one most often leveled against the film that you cite above. But I think Jack’s near-immediate descent into madness is part of the point. He’s been cracked by addiction and anger before he arrives. Nicholson plays that as a kind of caricature, though not so much for laughs as for emotional grotesquerie. Jack’s short-tempered and offers no demonstration of his supposed literary talent. He’s also fundamentally lazy. He sleeps until nearly noon and the scenes of Wendy doing all the work of maintaining the Overlook combine to form one of the film’s best running gags.

So, if I had to offer a grand unified theory of The Shining after this viewing, I’d say it’s fundamentally a satire of married life, though satire implies a kind of lightness that’s just not there. Nicholson plays to the rafters in his first falling-off-the-wagon scene with Lloyd but that doesn’t make the moment less spooky or sad. Tossing back that whiskey is the first of many one-way checkpoints he’ll pass through on his way to becoming a foaming-at-the-mouth axe murderer.

But the moment I decide to classify it as such I start thinking about what else is going on in the film. It’s also a film about the horror of a child recoiling at the horrors of the adult world. He already knows his father can hurt him. He senses that his parents’ marriage is on shaky ground, even before this becomes impossible to hide. And his paranormal abilities offer glimpses of all the awful things that have transpired in a place filled with adults and their adult desires and transgressions (including the murder of children).

It’s a slippery film, so maybe it’s more fruitful to talk about what it is than what it’s about. Specifically, I want to circle back to your observation that it doesn’t behave like any other horror film. I think you’re right. But how does it behave?

Scott: For one, Kubrick’s manipulation of time and space is so unusual and distinctive. I mentioned before about that early change of direction in Jack’s ascent to the Overlook—first by himself going right to left, then with his family going left to right—and the film, of course, ends with Jack getting lost in the hedge maze, after having been tricked by Danny and exposed to the elements for too long. Then there’s Kubrick’s strange, often hilarious use of timestamps, which movies normally use to situate us, but here are rendered utterly meaningless. The Torrances are supposed to stay at the Overlook for five months, but when we see titles like “Tuesday,” we don’t know where he are in that span at all. Horror films often like to destabilize audiences through different techniques, but I can’t think of any one as comprehensively shifty as The Shining.

You talk about the humor in the film but don’t get around to mentioning the absurdity of Dick Hallorann’s journey from his vacation idyll in Miami all the way back to Colorado just to get immediately axed to death upon his arrival. Kubrick takes his time with the whole sequence of events: Dick sensing a disturbance from Danny thousands of miles away, putting in multiple calls to the Forest Service in Colorado to check on the family, taking a Continental flight out west, battling terrible traffic conditions, and then grinding his way up the mountain on a snowcat. (Surely King had to be annoyed by Kubrick turning Dick into a cruel joke, since that character in the book helped Wendy and Danny escape and lived to see the epilogue.) It’s so perverse how Kubrick takes that much to set up the Dick character and follow his journey, only for it to be cut short so savagely. But such is life sometimes, you know? And Dick has one of the laugh-out-loud lines in the movies, when he tells the Forest Service people that the people watching the Overlook “turned out to be completely unreliable assholes.”

There’s also a fascinating interplay between very long scenes and short, sharp shocks. The Shining is talkier than you’d expect from a horror film, especially one about a spook-filled haunted house, but Jack does get that heart-to-heart with Danny on the bed and any time he settles into The Gold Room for a drink, the film settles with him, leading to exchanges like that long, unsettling conversation he has with Delbert Grady. The famous Steadicam shots of Danny zipping through the halls on his Big Wheel, with the isolated sounds of him going over carpet and hardwood, have the immediacy of propelling us toward danger. But a lot of the early scares come suddenly, like his encounters with the Grady twins down the hall or his gruesome visions of what had happened years earlier.

I’m fascinated, too, by Kubrick’s constantly moving camera in this film and how that plays into its sense of unease. It’s hard for me to articulate why movement on its own has the impact that it does, but in practical terms, Kubrick is dealing with an enormous amount of interior space with The Overlook. For any member of the Torrence family to get from one area of the hotel to another, they have to cover a lot of distance, and Kubrick chooses to have the camera unify that space rather than to cut. Again, we deliberately do not know the layout of the Overlook: For as much time as we spend there as viewers, we could not tell you how to get from the room where Jack does his writing to the family’s quarters or the distance between the kitchen and The Gold Room. That’s a very unusual strategy for any movie, much less a horror movie, because “good” filmmaking is supposed to establish spatial relationships.

As for a grand unifying theory, we have a handful presented to us in Room 237, and I honestly believe there’s something to the one about the film referencing Native American genocide. Small bits of production design like pieces of decor and the Calumet baking powder logo are not terribly persuasive to me, but it is mentioned that the Overlook was built on a Native American burial ground. In the past, I’ve thought about this detail as being an unnecessary add-on to the many other horrors that could explain why the hotel is haunted, but there’s something about that specific violation that seems meaningful, especially when we’re also told the Overlook is a hotel for presidents and other elites. That’s an ugly legacy.

Any other ideas for what Kubrick is getting at here, Keith? Is there some connective tissue to other work from him? And what moments freak you out the most?

Keith: I think part of why The Shining lends itself to so much theorizing is that it’s an elusive film with a lot swirling around inside of it. In addition to the ties to Native American history you mention above, Wendy asks if the Native American designs in the Colorado lounge are “authentic,” to which Ullman, the hotel manager, replies he believes they’re based on “Navajo and Apache motifs.” Both nations had (and have) presences in what’s now known as Colorado, but not so much in that part of the state. So if it is built on a burial ground, it’s unlikely the decor matches the original inhabitants. There’s nothing authentic about the tribute, which could be seen as yet another sort of insult. That said, it’s not like that reading unlocks the secret of The Shining. It doesn’t have to be about the awful history of American imperialism for that to serve as another unsettling element in an unsettled movie.

As for connections to other Kubrick films, broadly speaking I think Kubrick was interested in the breakdown of seemingly stable systems, be it a heist that goes wrong, international relations spinning into nuclear apocalypse, an advanced supercomputer, or a marriage unexpectedly thrown into a crisis that reveals some pre-existing cracks. The human passions of its characters sometimes seem like they mock the sculpted gardens and symmetrical 18th century architecture surrounding them in Barry Lyndon. (Age of Reason? Sure.) The tour given the Torrances doubles as an introduction to just how well organized and run the Overlook is, at least on the surface. The larder is stocked. Their job is simple. What could go wrong? But be it the ghosts of the Overlook, Jack’s own failings, or some combination of the two, they’re doomed.

More than any individual moments, it’s the atmosphere of The Shining that freaks me out. As you mention, it’s impossible to find your bearings in the Overlook. When Danny hides in the kitchen, for instance, it seems far away from where he left his father until it’s not. The film puts viewers in the middle of it and, after the lobby clears out at season’s end, we’re as alone there as the Torrance family. But some moments are undoubtedly freakier than others. As many times as I’ve seen this film, I never remember what corner Danny turns around and sees the Grady girls. (Sidenote: Why do the Gradys speak with English accents?) And while the Room 237 corpse that pursues Jack is appropriately terrifying, the moment before her arrival, when Jack thinks he’s embracing a beautiful nude woman, is just as disturbing in its own way. What is that expression on her face? Maybeit’s just knowing what’s coming that makes it disturbing. But maybe it’s not.

Scott, before we leave the Overlook, I have to know what freaks you out. And what do you make of the ending? The idea of the arrogance of America’s elite seems to be in play in Jack joining the July 4th party immortalized in that photograph (unless he was always there), doesn’t it?

Scott: Watching it this time—and again, the phrase “watching it this time” says a lot about how The Shining is experienced—I found a lot of my horror reflected in Wendy’s experiences and in Shelley Duvall’s performance, which is where we hang our sympathies as an audience. Part of Kubrick’s strategy throughout The Shining is a slow build-up of freaky events, often with Danny flashing on previous events or having a quick premonition. But toward the end of the film, as Jack is chasing his son through the hedge maze, this entire house of horrors crashes down on Wendy, who is tremulously grasping a kitchen knife as she comes upon Dick’s dead body, a cobwebbed lobby full of skeletons, and the elevators gushing blood. You can’t help but to think of how harrowing her life must have been before the Overlook even became a part of it, of trying to raise a son with a husband whose behavior could kindly be referred to as “volatile.”

To continue with Wendy, there’s a moment worth commenting on about an hour into the movie when she’s shown down in the boiler room with a clipboard, flipping different switches and essentially doing the job Jack is being paid to do. He’s the one who huffs and puffs about all the work he needs to get done—this is after he forbids her from entering the room while he’s writing—but she’s the one doing the caretaking, preparing meals, playing with Danny, and keeping Jack from exploding. In fact, the moment in the boiler room is followed immediately by Wendy responding to the horrible sound of Jack having an awful dream. She comforts him, even as he tells her the dream was about him killing her and their son and chopping them into little pieces. She’s constantly having to mollify him while finding the strength to protect herself and Danny and work her way through this awful situation. So much of the film’s horror is reflected in Duvall’s sad, exhausted, widened saucer eyes.

As for the ending, I think it does follow through on the notion of the Overlook as this vile, decadent palace for the American elite, with Jack’s mirthless grin occupying front and center. Haunted house movies are about legacy, right? A place is haunted or “unsettled” because of something terrible that has occurred in the past carrying over into the present. Hence the repeated line about Jack having always been there or having always been the caretaker.

Any final thoughts for you, Keith? I have a feeling our subscribers will have a lot to say about this movie.

Keith: The first thing that comes to mind in terms of final thoughts is the vision of the dog-suited man in a compromising position, but I think we might run out of space unpacking that here. Beyond that, it’s interesting to see this film ascending the charts rather than, say, Dr. Strangelove or Paths of Glory (which didn’t even make the top 250). The issue of Kubrick’s best films seems to be permanently unresolved, but it’s currently settled on the middle stretch of his career. That could change: to circle all the way back to Eyes Wide Shut, it’s been heartening to watch that film’s reputation reverse over the years. When the Blank Check podcast devoted an episode to it as part of its Kubrick run, I believe it was their consensus favorite Kubrick film. Maybe someone should dust off some space for it for the 2032 list. I, too, suspect this conversation will have a robust continuation in the comments section but we should probably end the main discussion here. Next up, we have a film that has so little in common with The Shining that I’m not even going to try to make a connection. We’ll talk it over in three weeks.

Next: Chungking Express

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

With regard to King's annoyance with this film, I think there's also something to Kubrick asserting himself as The Guy in a way that other directors had not and would not. Kubrick took what he wanted from the book and dispensed with the rest, which is a rare and exceptionally assertive approach to adaptation. He doesn't even really care about honoring "the spirit" of the text, which has to be humbling to an author of King's stature quite beyond his connection to Jack as a character.

Of course, Godard's bit about criticizing a movie by making another one really didn't work out for King, because the TV miniseries version of The Shining is bad even by network miniseries standards. Woof.

Wow, 77 comments and counting on this post. I knew THE SHINING was going to be a conversation-starter, but it warms the heart to see our humble little newsletter popping with the sort of activity we used to get at our giant websites of old.

Anyway, I think Kubrick deserves a little credit for feeling so guilty about faking the moon landing that he made a whole movie around it.