#90 (tie): ‘Yi Yi’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

On the invisible and not-so-invisible artistry of Edward Yang's epic drama about a family in contemporary Taipei.

Yi Yi (2000)

Dir. Edward Yang

Ranking: #90 (tie)

Previous rankings: #119 (2012)

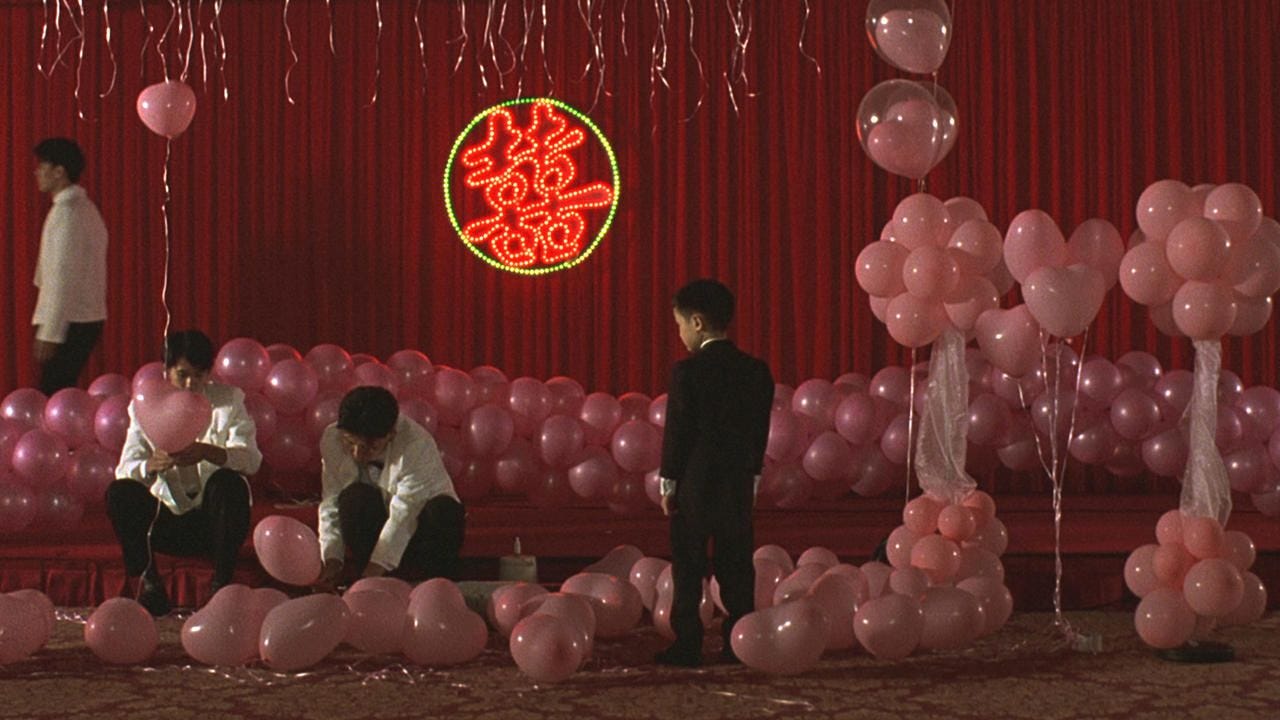

Premise: Yi Yi follows various members of the Jian family, middle class residents of Taipei, during a dramatic stretch between a wedding and a funeral. The wedding, which opens the film, is between the reckless, high-spirited A-Di (Chen Hsi-Sheng) and his pregnant bride Xiao-Yan (Shushen Xiao). While returning from a mid-reception trip to McDonalds with his son Yang-Yang (Jonatahn Chang), N.J. (Nianzhen Wu) unexpectedly bumps into Sherry (Suyun Ke), the girlfriend he abandoned while both were in high school. The chance meeting stirs up unresolved feelings for both of them, feelings that play out over the course of the film as N.J.’s depressive wife Min-Min (Elaine Jin) leaves the family for a Buddhist retreat and N.J. pursues a partnership for his struggling business in Tokyo. After leaving the reception early, A-Di and Min-Min’s mother (Ruyun Tang) falls into a coma while taking trash to a dumpster, a job that had been assigned to N.J. and Min-Min’s teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee). While wracked with guilt, Ting-Ting befriends Lili (Adrian Lin), a girl her age who lives in the high rise apartment next to the Jian family. Ting-Ting is drawn into a fraught affair between Lili and her boyfriend Fatty (Chang Yu Pang). Meanwhile, Yang-Yang takes up photography.

Keith: Scott, after finishing Yi Yi on Friday, I texted you “What a picture!” (sans the Pacino image from Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, alas), but I guess I need to expand on that thought here. This is my third or fourth time watching Yi Yi and I find myself in awe of it each time. Using the stories of an everyday Taiwanese family, Yang offers a sweeping cradle-to-grave depiction of human existence. Favoring long takes and rarely employing close-ups, Yang makes the film feel like something we’re observing but there’s not a moment that doesn’t feel artful, the work of a creator who realizes every detail matters.

An example: toward the end of the wedding reception that opens the film, A-Di stands atop a table next to his bride as revelers encourage him to drink a foul-sounding concoction called a “depth charge.” The eye naturally goes to A-Di, but toward the left of the frame there’s an attendee who’s so far gone he keeps passing out, awakening occasionally to cheer A-Di on, then returning to slumberland. It’s funny, but it’s also the sort of touch that suggests the fullness of the world in which the Jian family and those around them live.

That world is a particular time at a particular place. By the end of Yi Yi, I felt like I knew the details of the Jian family’s corner of Taipei extremely well, from the concrete underpasses that double as cover for romantic liaisons to the coffee shop promising “N.Y. Bagels” to the courtyard of Yang-Yang’s school. It’s a film that preserves its turn-of-the-21st-century moment quite well. (Oddly, and I have to assume this has since changed, it had never been released in Taiwan at the time the Criterion Collection recorded the supplements for its 2006 DVD.) But while Yang’s undoubtedly interested in the details of his setting, he’s even more interested in using it as a stage to play out the cycles of life and death and what changes and what gets repeated from one generation to the next.

The part of the movie that always takes my breath away happens almost two hours into the film’s nearly three-hour running time. On business in Japan, N.J. has arranged to reunite with Sherry. As they walk the streets, recalling their first date, Ting-Ting and Fatty share a similar experience in Taipei. Yang cuts the two dates together, letting the actions of each couple rhyme with the other, sometimes letting the voiceover from N.J. and Sherry’s reminiscences overlap with Ting-Ting and Fatty’s date (“The first time I held your hand we were at a railroad crossing going to a movie”) and sometimes letting the images speak for themselves. All the while, the trains and cars continue on their path and those around them go about their own lives, each undoubtedly just as dramatic in its own way. Yang poignantly folds history back on itself via methods unimaginable in any other art form.

Again: What a picture. And here’s where I confess that, while I’ve watched it repeatedly, Yi Yi is still the only Edward Yang film I’ve seen and I need to correct that. (We’ve got one ahead of us on this list, but I need to go beyond that.) Until Yi Yi, Yang kind of felt like a for-cinephiles-only secret. His film and others of the Taiwanese New Wave weren’t widely seen in North America. You can undoubtedly do a better job of putting this film in a broader context than I. And, since this film is a tapestry, do you find any of its threads especially striking?

Scott: I wouldn’t call myself much of an expert on Yang, because the only other film of his I’ve seen is A Brighter Summer Day, which we will both have a chance to explore again soon-ish in this conversation series, since it ranked #78 in the Sight & Sound poll. But until recently, it had been exceedingly difficult to see Yang’s work, and I only saw A Brighter Summer Day because a repertory house here in Chicago had some Yang prints and a friend invited me to a secret screening. (It’s a tremendous achievement, too, as you’ll see later.) Yi Yi was a special experience for me because it was a film I encountered early in my career as a professional critic, at the first Toronto Film Festival I attended in 2000. (Also seen: Memento, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, The Gleaners and I (with Agnés Varda in attendance, passing out food rescued from the trash), and In the Mood For Love.) It was before there were any expectations of blogging about the festival, so I just saw movies for 10 days, hung out with friends, and wrote an essay after I got home. It was a glorious time.) I knew that Yi Yi had a reputation coming out of Cannes, where Yang had won Best Director, but it was nonetheless a magical experience to see it premiere—at a public screening, since I was not yet on the press rolls—in a theater.

The sequence you mention, juxtaposing the reunion of N.J. and Sherry in Japan and Ting-Ting and Fatty on their date in Taipei, is without question the money sequence in the film. And I should say that it’s one of the many times that Yang’s shooting style, with its persistent medium shots or medium-to-long shots, pays off. (Side note: Before Criterion came along and gave the film a proper transfer, the DVD version of Yi Yi fell to Wellspring, which had the home video rights to many fine international films, but did notoriously crummy transfers, presumably for budget reasons. No film suffered worse than this one.) I hadn’t seen Yi Yi for 20 years before watching over the weekend for this project, and the shot of Ting-Ting getting her first kiss from Fatty under the overpass at night is completely burned in my memory. It’s such a moment out of time: As the rest of the world turns, with cars and motorcycles intermittently zipping around them and the traffic lights changing colors, you have this kiss that you know, for Ting-Ting at least, will be preserved in amber. It’s like a painting.

And yet, the purity of that moment gets so complicated by context, as does the reunion between N.J. and Sherry, which is anything but smooth sailing. One of the fascinating things about Yi Yi is how explosive the emotional eruptions are, right from the very beginning, when A-Di’s ex-lover turns up at his wedding banquet to tell his mother that it should have been her marrying her son and angrily demanding to see the “pregnant bitch” who’s wedding him instead. Then after N.J. just happens to bump into Sherry at an elevator for the first time in nearly 30 years, she comes back shortly thereafter to scream at him for not showing up for her (“I waited and waited. I never got over it.”), despite the fact that she remarried and appears to have set her life on a course to happiness and prosperity.

And so there’s nothing simple about the two relationships that Yang is juxtaposing in that sequence, even though the narrative and visual rhymes that he pulls off in the film are so exquisite. Ting-Ting is experiencing something like first love while N.J. and Sherry are recapturing a young love that is coming back to them so many years later. There’s swooning romance in that, too, that Yang brings out in the settings: The gorgeous nocturnal urban backdrop of Taipei and this seaside city in Japan where N.J. and Sherry are totally removed from lives they’ve built for themselves elsewhere. When you think about the most romantic times in your own life, I think they can feel, in memory, like the scenes Yang evokes here, as specific moments when it’s just you and your partner in this space and nothing else seems to exist.

And yet, there’s context. Extremely painful context in both cases: the relationship between Ting-Ting and Fatty has developed after Ting-Ting served as an intermediary between Fatty and Lili, her neighbor and his ex. She passes notes between the two, who’d she’d known to be a volatile pair, and then something develops between her and Fatty, which brings her tentatively out of her shell. Her essential innocence—nothing is said explicitly, but this seems to be her first romance, right?—winds up getting crushed by the true nature of Fatty’s relationship to Lili and to Lili’s mother, with whom he’d been engaging in what turns out to be a deadly love triangle. Fatty dismisses her coldly in the end, before he commits a crime of passion, and she has to live with the additional fact that she didn’t mean much to him. She was a mere distraction from a romantic obsession that was sending him down a much darker path.

As for N.J. and Sherry, their time away together gives them the luxury of rekindling an old flame and contemplating the possibility of starting over again. We already know that N.J., despite the outward signs of a conventionally satisfying family life, has been having trouble connecting with his wife lately. And can we really be certain that Sherry’s husband, a well-off American businessman, gives her much satisfaction beyond wealth? But there’s a dramatic difference between fantasizing about renewing a relationship that still has a spark and actually blowing up their lives to do it. When the two of them return to Tokyo, it’s like that magical bubble has burst and N.J. comes crashing back to reality: His company has scotched a deal that he’d wanted to make Mr. Ota (Issey Ogata, in a tremendous performance) and Sherry has checked out of the hotel without even leaving a message.

Oh there’s so much more to talk about here, Keith. Let’s pull back and look at the bigger picture. One feature of the wave of Taiwanese films coming out at this time—from Yang, from Tsai Ming-liang, and from some of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s work—is a theme of alienation. What’s your takeaway from how this family operates? They live together, but only rarely interact, despite the film opening with a wedding and ending with a funeral, both family events. Yi Yi made me think of The Ice Storm in that it expresses the distance a family of four has from each other by sending them off on separate adventures.

Keith: I think The Ice Storm is a good point of comparison for all the reasons you mention above and one more: both films end with a kind of guarded reaffirmation of the safety of family and home, whatever its flaws. N.J. and Min-Min reunite and, though we know Min-Min’s not the love of N.J.’s life and it’s pretty clear that he doesn’t stir her passion, either, they’re still committed to each other. Ting-Ting inches out of the home and comes close to becoming embroiled in a situation more dangerous than merely spending the night in a hotel with Fatty, which is already beyond her comfort level. Even A-Di has found a sort of stability as the film ends (though this seems unlikely to last).

One way of looking at the film is as the story of characters who narrowly avoid the sorts of plots seen in other films. There’s a moment toward the end, for instance, when it seems like Yang-Yang might have drowned but Yi Yi isn’t that sort of movie. The heated, bloody drama that plays out between Fatty, Lili, and Lili’s mother exists on the margins. For all its notalgia and romance, there’s no wistful melancholy or bittersweet sense of what might have been in the way N.J. and Sherry’s reunion ends, just different varieties of regret and resentment. Maybe it’s the family, however troubled and disconnected, that keeps them all safe.

It’s not quite that simple though, is it? One of the most remarkable qualities of Nian-jen Wu’s performance is the way he makes N.J. seem younger in the middle part of the movie than he does at either end. Reuniting with Sherry doesn’t just remind him of his youth, it seems to restore it. When Ota refers to the couple, both in their mid-40s, as “young people,” it doesn’t seem absurd. And while Fatty is ultimately revealed as capable of dreadful acts, he’s also a philosophical (and movie-loving) soul fond of quoting an uncle who says “we live three times as long since man invented movies” because “movies give us twice what we get from daily life.”

I don’t know if Fatty’s acting as an Edward Yang surrogate when he says that, but I don’t think little Yang-Yang’s journey is just cute comic relief, either. He takes pictures of the backs of heads because this is a side of their lives his subjects never get to experience. That seems like a child’s version of the sort of artistic impulse that might ultimately mature until it’s capable of making something like Yi Yi. Is it a coincidence that the camera-toting kid shares a name with the director? (It also reminds me of a phrase that turns up a couple of times in Ulysses: “See ourselves as others see us.”)

In an essay for Criterion’s website, Bryan Washington shares a quote from Yang’s notes for Yi Yi: “I’d like viewers to come away from the film with an impression of having been with a simple friend. If they came away with the impression of having encountered ‘a filmmaker,’ then I’d have to consider the film a failure.” It’s a curious quote, in some respects. Yang’s style is deceptively simple but it’s not exactly invisible, particularly in moments like the twin date scene referenced above. But Yi Yi is also not the work of a director pushing viewers toward some grand truth that needs to be shared, either. It’s a gentle and observational film that erupts into moments of high passion, sometimes unexpectedly. But even in these moments, it feels like a film that wants viewers to draw their own conclusions and makes clear that even characters making bad choices (or worse) have their reasons. A different film might have judged Min-Min for leaving her family for a (pretty obviously scammy) religious organization, but the image of her staring out a window into the night sky that precedes her departure captures a woman who has to do something.

I’m trying to think of another film like it. Do any other films as humble in subject and epic in scope come to mind? And what filmmakers does Yang’s style evoke for you?

Scott: The big point of comparison for me—the one I wrote in all-caps as I was writing notes on this viewing—is Tokyo Story, which also has that gentle, prevailing theme of regret running through it, along with the city trains. Toward the end of the film, after she’s discovered that her first love is a murderer, Ting-Ting tearfully asks her grandmother, “Why is the world so different than what I thought it was?” I couldn't help but flash back, at that moment, to the most famous scene in Tokyo Story, when Setsuko Hara’s character is asked “Isn’t life disappointing?” and she responds in the affirmative, with a heartbreaking half-smile on her face. Hara’s character is between Ting-Ting and N.J. in age, having lost her husband but not her youth, yet they all share a feeling that a pathway to happiness has been shut down for them. Perhaps, as you say, the ending affirms the family unit, but I think it’s been deeply compromised and certainly not what N.J. and Min-Min might have envisioned for themselves many years ago. They stay together because what choice do they have now?

Let me shift to Min-Min for a bit, because I love the way that storyline plays out, even if she disappears for a large chunk of the film. First off, I love Yang’s choice to turn her mother’s comatose state into a dramatic device: the family needs to talk to her and she can’t hear or respond to what they say, so she’s essentially a confessional for people who don’t confide in each other. Yet N.J. comes home one day to find his wife in tears, because she has nothing to say to her mother beyond the empty routines of her day-to-day life. Min-Min wonders if those routines are her life, which is the existential crisis that sends her looking to a shady spiritual operation for guidance. N.J. doesn’t necessarily lack sensitivity, but he tries to bring her back to the practical problem of his mother-in-law needing people to talk to her. And so gives the worst possible answer, suggesting that they ask the nurse to read the newspaper to her.

If you’re looking for some source of optimism in Yi Yi, though, I’d turn to my favorite character in the movie, Mr. Ota. “Every day in life is a first time,” he says in one of his meetings with N.J. “Every morning is new. We never live the same day twice.” When N.J. goes to Tokyo for a planned week of negotiations with Ota’s company and Sherry flies into the city, too, Ota smiles over the possibilities. It’s only going to take them one night to get the deal done, he says, so the rest of the week is free for however N.J. and Sherry want to spend it. Ota seems to live his life with a sense of spontaneity and whimsy, like when he opts to tickle the ivories at a karaoke bar. And it follows that his proposal is the riskiest for N.J.’s firm, the one with the potential for the highest gain and biggest loss. You can see that he’s pleased by the opportunity to give oxygen to this rekindling of old flames, and that perhaps this will lead to a new morning for both of them. They can’t make it happen, but he likes the possibility. To me, Sherry leaving town at the same time N.J.’s firm goes for the less risky (and ultimately bad) choice are connected events. A one and a two, to translate the title.

What stands out to me most about Yi Yi is the low-key mastery that Yang seemed explicitly intent on achieving. He provides the film with a sturdy structure—beginning with a wedding, ending with a funeral, and exploring the fullness of life in between—and a lot of internal rhymes, too, as if this were an epic poem. And yes, there are also the rigors of his medium-shot style and the stunning use of reflective surfaces. But mostly there’s the quiet confidence that the lives of these four characters, sometimes together as a family but mostly drifting off on their own, will carry a collective observational weight. As masterworks go, it’s not terribly flashy.

But it has a little flash, doesn’t it? Or at least some memorable moments. What are some of the standout scenes or touches for you, Keith? I have a few I’ve been holding back.

Keith: Yang’s style often feels like we’re simply watching life unfold, which is effective for many reasons, including capturing the feeling of a situation spinning out of control. We get that a little bit during the wedding that opens the film, but that ultimately serves as mere prologue for the baby shower scene, where the tension created by the arrival of A-Di’s lover escalates until it explodes — which then pays off with a shot of N.J. looking on in deadpan disbelief.

But I think my favorite moment, barring the double date sequence, is another instance of what Kent Jones calls Yang’s “poetic overlapping.” Late for class because he was attempting to drop a water balloon on the girl who’s been tormenting him all movie, and whom he’s been tormenting in turn, he arrives as a nature movie is still in progress. As the narration turns to how thunder works by opposite forces attracting and how lightning might be the source of all life, the girl arrives and a lightning flash on screen frames her in a way that makes Yang-Yang see her in a new light. But Yang’s not done: he then cuts to a street outside where a rain is falling and Ting-Ting spies Fatty across the way. Just masterful stuff. Again: what a picture. How about you?

Scott: Oh God, such a beautiful sequence. And a surprising shift in tone, too, because it follows a piece of comic business where the water balloon lands on the dean’s head. Yang-Yang ducks into that room and has a completely different experience that sets his mind toward seeing girls in a new way. (And I’m relieved the poor kid didn’t drown, either. To make it seem like he did, only to have him turn up later without comment, is a nice reversal of expectations. Feels like I wasted a lot of money on my kids’ swimming lessons when they could have just been holding their breath in the sink.)

As for other favorite moments:

• I like everything with Ota, but the karaoke bar scene perhaps most of all. It’s a joy when Yang cuts to Ota playing piano accompaniment to another singer (“He plays well for a computer guy”), but then he solos on Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” and the melancholy of the film just washes over you. That prompts N.J. to head back to his empty office at night and finally call Sherry, grateful that she doesn’t answer so he can leave her a message without stumbling over what he wants to say to her.

• Yang-Yang’s interest in photography eventually leads to that series of photographs that he’s taken of the backs of people’s heads, so they can see what they could otherwise not see. But like any artist, the boy has his developmental period, too, which in his case involves trying to take pictures of mosquitoes and getting a lot of blurry shots of walls and ceilings instead. The dean mocks him as “avant-garde.”

• Another Ota scene: At the restaurant where he’s finally negotiating the deal with N.J., he borrows a pack of cards to demonstrate a magic trick he learned as a child, when he wanted to be a magician. Ota tells him that the trick isn’t magic at all; he simply knows where all the cards are in the deck. That leads him to express his pessimistic instincts on the deal: “I have no magic to save your company. I’m just like you. I have no tricks. We can work together, but I think your partner wants a magician.”

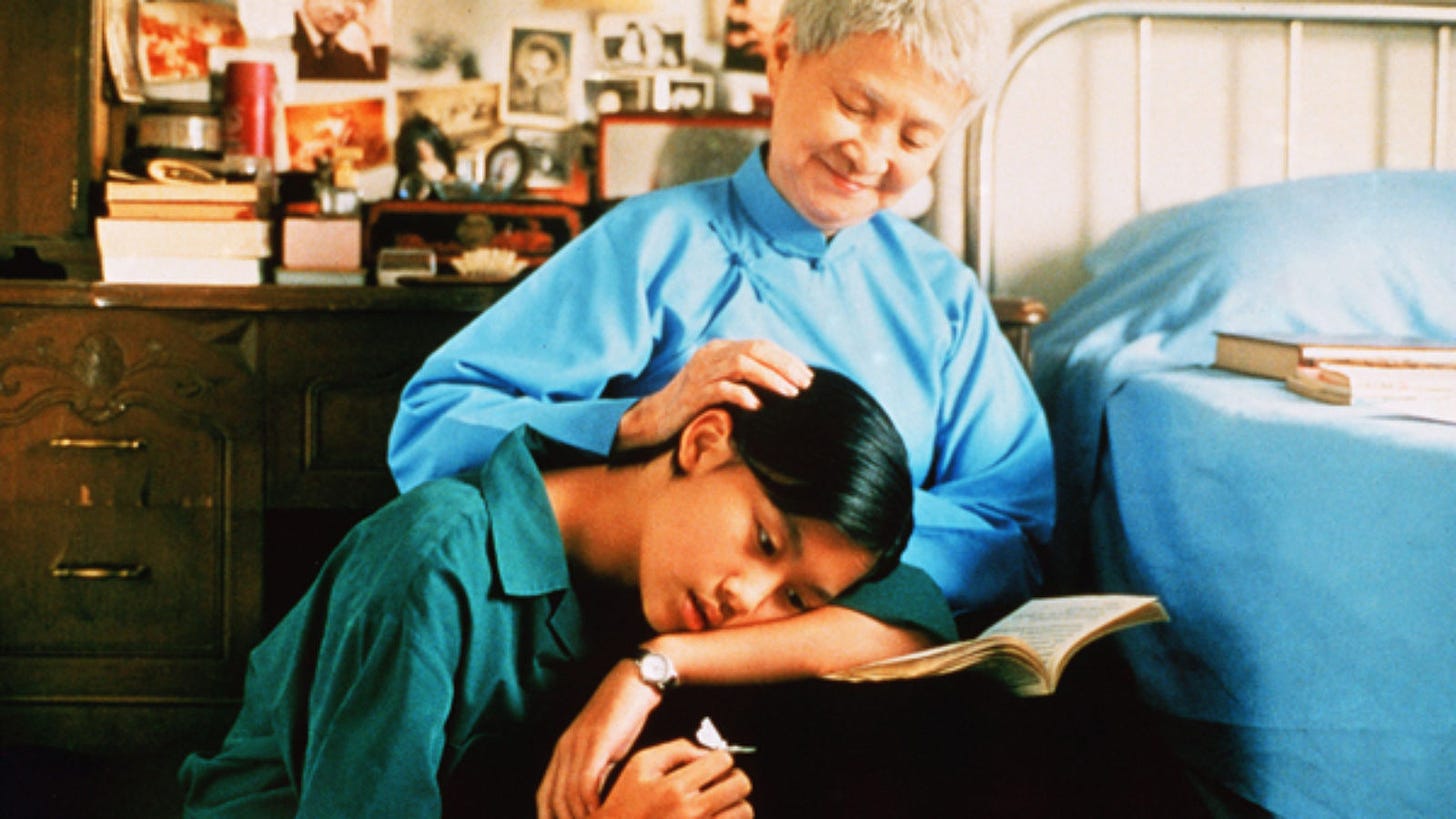

• Oh god, that scene where Ting-Ting finally falls asleep and imagines her grandmother awake and sitting peacefully by her bed, where she constructs that little paper butterfly for her. When she wakes up, her grandma has died, but she still has the butterfly. Movie magic, folks.

Next: Ugetsu (1953)

Previous entries:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

Loved this discussion! For Thanksgiving 2020, my husband and I were by ourselves because of the pandemic so we spent the day watching A Brighter Summer Day and Yi Yi and called it Yangsgiving. The themes of Yi Yi were particularly appropriate for a day that we'd usually spend with friends and family.

(Side note: We went to Taiwan for vacation earlier this year and made a quick detour to walk by the apartment building from Yi Yi. The building exterior and highway still look very much like the film!)

Historical correction - Yi-Yi was somewhere in the nineties (definitely in the top 100) of the 2012 Sight & Sound critics poll. I'm guessing the ranking you had was the aggregate of the critics and directors poll - I don't think, but don't know, it didn't make the top 100 in the directors poll.

I rewatches it earlier this year for the first time in nearly 10 years. Remembering there was tragedy at the end and the scene of Yang Yang jumping in the pool, I actually couldn't remember as I was rewatching it, if he drowned or not.

I think all of my favorite scenes have already been mentioned (the educational film about storms, nearly every scene with Ota...)

I will say, since there's the discussion of availability of his films, I am aware of Taipei Story is on the Criterion Channel and Terrorizers is on Mubi.