#78 (tie): 'Sátántangó': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

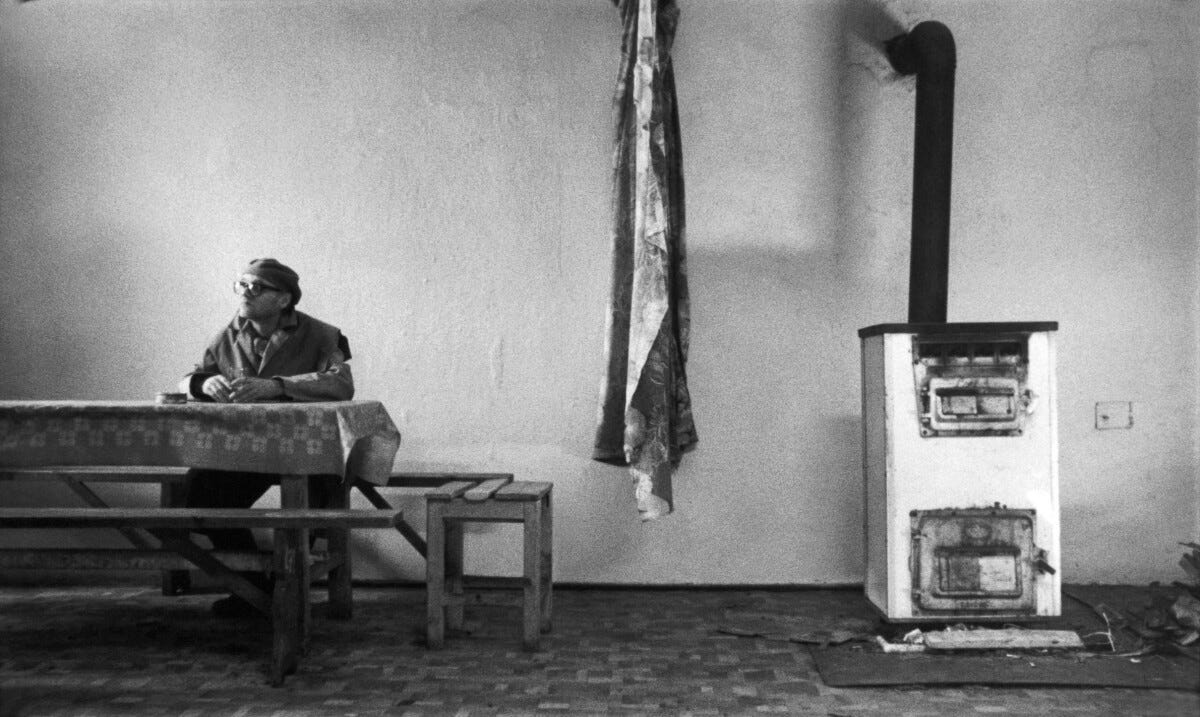

Bela Tarr's bleak and disturbing depiction of a Hungarian village in deep decline is as mammoth as it is captivating.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Sátántangó (1994)

Dir. Béla Tarr

Ranking: #78 (tie)

Previous rankings: #38 (2012).

Premise: Unfolding in 12 overlapping, achronological parts, Béla Tarr’s seven-plus-hour adaptation of László Krasznahorkai’s 1985 novel takes place mostly in a small, desolate Hungarian village where residents are facing the collapse of their collective farm. With their futures looking bleak and uncertain, an air of suspicion settles over the town as they puzzle over the fate of a large payment and conspire over how to spend the money—and who gets it. In a situation ripe for exploitation, along comes the charismatic Irimiás (Mihály Vig), a villager who had been presumed dead but now reemerges with a plan to pool everyone’s money and resources and start a new collective at a nearby estate. Meanwhile, Tarr checks in on other major characters, too, including The Doctor (Peter Berling), who embarks on a wayward journey in an attempt to refill his fruit brandy, and Estike (Erika Bók), a little girl whose deception at her brother’s hand leads to tragic results.

Scott: Here we are, Keith, atop the Mount Everest of modern-day cinephilia. (Or at least K2 in the Himalayas, if you want to consider something like Jacques Rivette’s 773-minute Out 1 as the higher peak.) Sátántango is not the longest film on the Sight & Sound list—that would be Shoah at #27—but it has a reputation as one of the most formidable achievements of the last 30 years, bolstered for quite some time by the difficulty of seeing it. Until Facets finally released the film on DVD, repertory screenings of the film were marathon events in cities like Chicago, where fans would submit an entire day to sold-out shows. The phenomenon led me to include the film as a New Cult Canon entry, and you got to be part of the communal experience earlier this year, Keith, when the Gene Siskel Film Center included it in a “Settle In” series that also featured films like Berlin Alexanderplatz, Star Spangled to Death and Fanny and Alexander. I’m anxious to hear all about it, because I’ve only seen this movie at home.

And what an extraordinary experience it is! From the famed eight-minute establishing shot that opens the film, Tarr seems to advise you to “settle in” just as the Film Center did, drawing you into a muddy bog that feels like the Hungarian equivalent of the dying town in Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show. Both films are shot in black-and-white, both are about a place without a future, and both feel so conspicuously unpopulated that the wind whistles through the streets and buildings, undisrupted by human activity. Tarr doesn’t fill in the political details about how this town has collapsed, and there’s really not much to unpack here story-wise, given that the film is about a pool of money that the villagers are coaxed into handing over to Irimiás, a false prophet. And so the look and tone of Sátántangó as an epic slice-of-life, along with its philosophical and existential underpinnings, is what Tarr has given us to consider. You don’t merely watch the film. You’re immersed by it.

This is only the third Tarr film that I’ve seen. The others are Tarr’s final two features, 2007’s The Man From London, a peculiar noir (with Tilda Swinton) that he wrote with Sátántangó author László Krasznahorkai, and 2011’s amazing The Turin Horse, which feels from the start like the retirement film he declared it to be at the time. The horse of the title references a story about Friedrich Nietzsche encountering a stubborn old horse that had been whipped mercilessly by a coach driver, and that sets the stage for a film that shifts focus to the coach driver and the bleak circumstances that define his day-to-day life. As with Sátántangó, there’s almost an apocalyptic quality to the film, a sense that we’re seeing the last generation plodding and suffering their way to the grave. There are no children in The Turin Horse—the coach driver’s daughter is older and subsists on the same boiled potatoes in their one-room country cottage—and it’s obviously significant that the only child in Sátántangó winds up swallowing a fistful of rat poison. Even at her age, she can see plainly that she has no future—or, at a minimum, that she’s surrounded by people who treat her with either neglect or deceit.

Perhaps there was a time when the members of this community were more united in their plight, but when the film starts, they’re irrevocably fractured, divided into conspiratorial groups over what to do with the money they have. If there was ever any promise of security and sustainability in this place, perhaps by the communist government, it has been broken and there seems to be no path forward other than leaving entirely. Tarr spends some time in individual chapters getting to know certain villagers and giving a sense of the town as an organism, which inevitably leads to the small tavern where they go to drink and dance their troubles away. But from his first introduction at a pub in another city and then later in a stirring speech at a funeral gathering, Irimiás—played by Tarr’s longtime collaborator Mihály Vig, who also composed the memorable score—has a level of magnetism that no one else can approach. In these dire circumstances, he has a diabolical, messianic power that they can’t resist. Who else has a vision for what to do? (And, cynically, is Irimiás going to be just another greedy leader of the sort that got them into their current predicament?)

There’s a lot here to discuss about the unusual structure of the film and some of its more famous sequences, like the notorious chapter about a little girl taking her powerlessness out on a cat, but I’d like to hear from you first, Keith. What was it like to spend a cold Chicago day in the company of Sátántangó cultists? Did you feel like seeing it projected was an essential part of its impact? And what did you take away from Tarr’s view of humanity?

Keith: I did indeed settle in, and I’m glad I did. I’ll never say you haven’t seen a movie if you haven’t seen it in the theater, because I’ve never seen many of my favorite movies projected. But I’m happy I got the chance to see Sátántangó as it was meant to be seen: in a room full of cinephiles so rapt by the movie we were able to ignore just how stale the small theater smelled by the time we reached hour seven. (We got two breaks and I texted an update to my daughter at the second, when two-and-a-half-hours remained. Her response: “You only have the length of a long movie left!”)

I’d rather see just about any movie in a theater if given the chance, but I think two types of movies really benefit from the theatrical experience: big spectacles and slow-moving films (of whatever length) that require a lot of concentration. Just the mere knowledge that cheese and crackers are just a push of the pause button away can be distracting when a film demands close attention to every detail. Sometimes it’s good to be held captive.

I left the Siskel a bit woozy from the experience, but I think the film had as much to do with that feeling as the act of sitting still in a theater seat for so long. I think asking about Tarr’s view of humanity is a good place to start, and I suspect we’ll keep looping back to it—Sátántangó style!—throughout this conversation. It’s bleak but it’s not just bleak. This isn’t a misanthropic film so much as an expression of a profound disappointment with humanity itself: our weaknesses, our foolishness, and our tendency to follow the loudest voice making promises of a better tomorrow no matter how unlikely those promises sound. It’s a work of pity more than contempt.

It’s also a film about how we fall into the same patterns of behavior. There’s a scene shortly before the four-hour mark in which much of the village piles into a tavern—though that sounds like too cheery a word for where they’re drinking—and dances to a tune that repeats and repeats and repeats. I just checked the running time of the scene and it’s around twenty minutes, but I would have guessed something closer to an hour. It’s one of those rare movie moments that can make you think you’re losing your mind, and I don’t think that’s by accident.

I’m sure we’ll return to that and other memorable moments, but since you brought up the cat, we may as well get that out of the way.

I avoided watching this film for years because I knew there was a scene in which a cat is tormented on screen: a real cat and real torment. My understanding is that, even though we see the cat seemingly die from poison, the real cat was fine, but even in the best case scenario, that cat was fine after undergoing some harsh treatment. Scott, I hated watching this. There were times when I couldn’t watch it. I was talking to a friend of ours during the break and we both shared the instinct to flee. I understand this is almost certainly the feeling Tarr wanted to evoke, but I honestly think this works against the movie. I found myself thinking not about the cat in the story but the real cat in the movie. Sátántangó is an immersive experience but this ruins the illusion. Beyond the ethics—and I’m someone who believes no animal should be made to suffer for entertainment—it works against the movie. I greatly admire this movie and I’m glad I finally saw it. In fact, I think it’s a masterpiece unlike anything else I’ve ever seen. But readers should consider a giant asterisk attached to all my praise.

Scott, let’s get the cat talk out of the way. What are your thoughts on that scene? And do you find this film as pessimistic as I do? We should also get into the fact that it’s a very funny movie at times. But I’ll let you take the lead on that. I’m still thinking about the cat.

Scott: Are we sure that an animal has been made to suffer here? Obviously, this entire sequence is disturbing and upsetting and I wouldn’t condemn our fellow animal-loving cinephiles from tapping out on it, but Tarr has been asked about the cat many times in interviews and he has been emphatic about its treatment not constituting abuse. There’s a little bit here on it in a Jonathan Rosenbaum interview from 2001, but this 25th anniversary piece in Little White Lies is chippier and gets into more detail. In broad strokes: The girl’s wrestling with the cat was rehearsed and the terrible noises that it makes were added to the soundtrack from a sound archive. The scene where the cat takes the poison and slowly falls asleep was done in collaboration with a veterinarian. If you put a cat down—and you and I have both been in that situation—the animal gets sedated before the second, lethal injection. My assumption is that the cat was medicated thusly. (That was very hard to watch for me, just because I’ve been in that situation before.)

As for the chapter itself, called “Unraveling,” it’s my favorite stretch of the entire movie, so I guess we’re at odds there. For one, I think it’s essential to a movie in which a community is breaking apart and eventually gets scattered to the winds—which, in a Béla Tarr film, can look a lot like oblivion. This little girl, Estike, carries a lot of symbolic weight as the future and her tragic odyssey in “Unraveling” is a microcosm of what happens to the adults. Her own brother, desperate and greedy like everyone else, collects her meager savings and digs a hole for it to grow into a “money tree”—which seems ridiculous, but was the pre-internet Hungarian version of cryptocurrency. His betrayal of her trust foreshadows her elders’ betrayal later at Irimiás’s hands and, to me, makes the speech he gives to them after her death all the more resonant. He talks to them about the child as a “price” that they have paid; she perished, he says, “so our star can finally rise.”

I mean, that face. The one simple, common connection between all the Tarr films I’ve seen are the faces, which are so distinctive and so studied by the sheer amount of time he keeps the camera rolling on them. (It says something that the one movie star I’ve seen in a Tarr film happens to be Tilda Swinton.) You have to remind yourself that Estike is a child, because the moment she turns to the cat, she has a firm and very un-childlike understanding of the world. Her words speak as loud as her actions: “I can do whatever I want with you.” “I’m stronger than you.” “When you’re dead, I won’t feel sorry for you.” In this last day of her life, she chooses to torture the only creature on earth that she has power over. It’s excruciating to watch, of course, but it should be excruciating. And when we get to that long tracking shot of Estike walking down the muddy road toward the camera, cradling the dead cat, it’s heartbreaking to watch.

I love what you wrote about the film’s overall POV, so I’ll quote it again here: “This isn’t a misanthropic film so much as an expression of a profound disappointment with humanity itself: our weaknesses, our foolishness, and our tendency to follow the loudest voice making promises of a better tomorrow no matter how unlikely those promises sound. It’s a work of pity more than contempt.” There are certainly times when we recoil at the small-mindedness and treachery of these characters, but even then, you recognize that the world is closing in on them and they genuinely don’t have any idea what to do. That makes them vulnerable to a loud voice, as you say, and I think we also need to acknowledge the invisible forces that put them in this predicament. This was once a collective farming community and the lives they were promised, austere as they are, have been taken away from them.

And so you get sequences like that mad dance at the tavern, which does indeed feel like it lasts forever—or, at least, so long that even “Weird Al” Yankovic would blanch at that much accordion. There’s little joy in this drunken ritual, either, or little warmth evident between the tavern’s denizens, who obviously know each other well but not affectionately. The tavern dance is also a moment where the conceit of the overlapping chapters pays off. We see two different angles of Estike peering through the window from the dark, rainy night outside: First from the back, in the “Unraveling” chapter, and then a second time in a later chapter where we see her face from the inside. At this point in the movie, we know that she dies. To see her alive in that moment, from the outside looking in, is so goddamn haunting.

We haven’t talked much about the structural tricks of this movie, which toggles back and forth in time like a “tango.” Was it effective for you, Keith? And given your discomfort with the animal-harm chapter, I’m curious to know if there’s a section of the film that wowed you. What do you make of The Doctor, as both character and narrative device? And are there any specific moments or images that have stayed with you in the months since you saw this movie on the big screen?

Keith: Well, I wouldn’t say that the “Unraveling” section didn’t wow me. Quite the opposite, I guess, as it affected me deeply and it’s reassuring to hear Tarr’s account of how it was accomplished. But I still think that when a live animal appears to be in jeopardy in a movie, it has a distancing effect (and I’m not entirely on board with the thought that sedating a cat for the scene is ethical, but I don’t want to sidetrack the discussion any further, so let’s let the matter find a sunbeam and curl up for a long nap).

As for what’s stayed with me, the long opening shot touring the village is as memorable as any other stretch of the film, establishing a sense of near-total devastation. Also striking: an early shot of Irimiás and his companion Petrina (Putyi Horváth) that follows them from behind as they walk through a gusty, trash-strewn alleyway. (It’s this shot and some similar moments that Gus Van Sant would borrow from liberally for the Tarr-inspired Gerry.) There’s also that odd scene in which Irimiás meets with a dealer about obtaining “quite a lot of explosives.” We never find out why and this seems to be a dangling thread. But the moments prior to the dealer’s arrival are the closest we get to an explanation of Irimiás’s character, or at least how he sees himself, when he tells the dealer, “Don’t take me for a liberator. Think of me as a tragic researcher investigating why everything is as terrible as it is.” Irimiás sets the plot in motion, but that line almost makes him sound like he’s giving voice to the director.

Or maybe Tarr maps more easily onto the Doctor (or both). The film switches between times and points of view, but it’s in some respects the Doctor doing the telling. He keeps a notebook and is at the center of the film’s final sequence, which concludes with him retreating not just to the home he rarely leaves, but into darkness as he boards himself up against the world. The church bell is being rung by a madman afraid of the Turks—it’s a film in which it’s impossible to put the past behind, even long-ago history—and he’s seen nothing but tragedy and madness every time he leaves and walks among his fellow citizens. It’s bleak stuff! But he also feels like an appropriate central character.

Scott, it feels like we could go on and on with this film (just as it goes on and on). Rewatching a few scenes to refresh my memory has only confirmed how haunting it is, and how strangely beautiful in its unrelenting bleakness. But does it offer any signs of hope? And do you think its view of this village should be seen as a universal condition?

Scott: I really don’t see it as hopeful at all! And there’s a lot of integrity to that, because movies are often engineered to give us at least some sort of silver lining. The same week I re-watched Sátántangó for this series, I also happened to re-watch Kenneth Lonergan’s great Manchester By The Sea, and was awed again by a similar follow-through: Here’s a movie about a man returning to the scene of the defining tragedy of his life and determining that he ultimately cannot stay there, despite our expectation that maybe he’ll “beat it,” to use his words. I think Tarr is making a very definitive end-of-the-world statement here, in that you have a community that is dying and cannot be revived, certainly not with Irimiás holding the defibrillator paddles. From the beginning, you wonder what could grow in this muddy bog—what has ever grown there—and where residents, all of them middle-aged and beyond, could go now that the collective farm has fallen apart. A younger man like Irimiás is able to trek there from what looks to be a larger city, but Tarr makes the distance seem so impossible to bridge, as if they’re cut off from civilization. Even in the city, you have that famous shot of Irimiás and Petrina walking through a windstorm of alleyway garbage, which doesn’t exactly promise Shangri-La.

As to your question about whether Tarr is describing a more universal condition, I’m not so sure. His unwillingness to get into the political and economic specifics about what landed the townspeople in this place suggests that maybe he does intend for a broader portrait of human struggle, rather than, say, the collapse of a desolate rural community after a change in policy. I kept thinking about the small Midwestern towns I’ve been through where the city center is lined with boarded-up businesses, with no hope of revival, and the long-ago promise of prosperity that must have been broken. So even if Tarr had a particular Hungarian village in mind, Sátántangó seems resonant to plenty of devastated communities while also seeming like a world unto itself. And that’s the main takeaway I have with the whole experience of the film: By spending as much time in that place as we do—and in the way we do, with Tarr’s long takes and the textured black-and-white photography—you feel completely immersed in it. I think that’s why the heartiest of cinephiles keep wanting to come back to it, even if it’s not the type of film that we usually call “escapist.”

What about you, Keith? Any final thoughts? Maybe an image that sticks with you? You mentioned the influence on Gerry, but the film inspired a whole trilogy of Gus Van Sant movies (Elephant and Last Days) that I still consider one of the most exciting of his career. And I think modern-day “slow cinema” wouldn’t be the same without it.

Keith: It makes me want to go back to those Van Sant films and look for the influence. And, for that matter, to seek out more Tarr movies as this is relatively unknown territory for me. Starting here seems likely to help unlock the others. As for the slow cinema connection, it does feel like a key piece of what was happening elsewhere in the 1990s and 200s, doesn’t it? Sétántangó links up well with Yi Yi, Kiarostami’s films, Goodbye Dragon Inn, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and what was soon to happen in Romania, doesn’t it?

As for us, our next stop is closer to home as we move past the many films tied at #78 for the first of three tied at #75 : Douglas Sirk’s 1959 adaptation of Imitation of Life. I’m looking forward to it and, if you’re playing along at home, it’s worth also watching the 1934 version starring Claudette Colbert.

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

Werkmeister Harmonies is one of my top-five favorite movies. I loved the (approximately) first half of Sarantango but could not stomach the cat scene and walked out midway.

I believe Bela Tarr that the cat was not tortured, clearly sound effects were doing a lot. But I cannot convince myself that I was seeing footage of an animal being well-treated. It's hard for me to reconcile that with a filmmaker whose work I've otherwise loved.

I've been lucky enough to see the film three times theatrically with enthusiastic audiences: once at the old Fine Arts (theater #2) during the Chicago International Film Festival in 1994, and twice in later years at Facets. It think it really says something that at the CIFF screening Tarr was present, and most of the audience stuck around another hour for a Q&A.