#78 (tie): 'Modern Times': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Charlie Chaplin bid farewell to silent moviemaking and his signature creation with a comically inventive piece of social commentary.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Modern Times (1936)

Dir. Charlie Chaplin

Ranking: #78 (tie)

Previous rankings: #35 (2012), #62 (tie, 1992)

Premise: The Tramp (Charlie Chaplin) begins the film working the assembly line in a mammoth factory. The stress of the job, as depicted through some elaborate comic set pieces, pushes him toward a mental breakdown. Jailed after he’s mistaken for the leader of a communist protest, The Tramp is released from jail after thwarting a breakout. But, back on the street, he finds employment hard to come by, though he’s newly motivated after befriending a spirited gamine (Paulette Goddard), who becomes his partner. More mishaps in employment and economic distress follow, including a stint as a department store’s night watchman and a singing waiter.

Keith: Speaking broadly, most of the films on the Sight and Sound list belong to the height of the sort of film they represent. Looking back at what we’ve covered already, Once Upon a Time in the West comes from the peak of the spaghetti western. Ugetsu Monogatari comes from the blossoming of Japanese films in the years after World War II. Etc. That can’t be said of Modern Times, a (mostly) silent film made almost a decade after the premiere of The Jazz Singer. But a lot had happened in those nine years, and it’s a testament to Charlie Chaplin’s stardom that he was able to continue working as he always had, making silent comedies even after his contemporaries had either transitioned to sound (with varying degrees of success) or called it a day. There’s an autumnal sense not far beneath the surface of Modern Times. Chaplin had considered making it a full-on talkie. Instead, the film finds him attempting silent comedy on a scale he’d never tried before, as if realizing he might never get a chance to do it again.

Chaplin hadn’t released a feature in five years, most recently City Lights in 1931 (which we’ll be arriving at later). But he’d remained a celebrity and Modern Times is informed in part by world travels in which he’d met everyone from Winston Churchill to Mahatma Gandhi to Henry Ford. Both Gandhi’s criticism of technological advances and Ford, who’d done more than anyone to escalate the rate of production in the 20th century, informed Modern Times. The film’s filled with jokes and gags but the title’s not one of them. This is Chaplin making A Statement.

But what kind of statement? Chaplin’s politics leaned left, which led to a shameful exile from America years later. But Modern Times keeps the political personal. We never stray from the plight of The Tramp and, a bit later, The Gamine. It’s a film about two have-nots and their bumpy ride through some of the toughest years of the 20th century, economically speaking. The Tramp has always been an exceptional figure in Chaplin’s movies, announcing himself as a misfit from the moment he toddles into the frame. But he’s also been a stand-in for the Everyman, never more than here.

Yet for all that, I think this is also one of Chaplin’s funniest films, great from start to finish but never better than in its opening scenes, in which The Tramp’s attempts to work on an assembly line cascade into chaos. It’s as graceful a marriage of comedy and commentary as I’ve ever seen. Scott, what are your overall thoughts on the film? And I want to go deeper into individual bits, but let’s talk first about the opening stretch I’ve already mentioned, which takes place in a dehumanizing environment not that far removed from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (also ahead on the list). It immediately announces that Modern Times has more than laughs on its mind, doesn’t it?

Scott: Oh, without question. From the opening shots, which juxtapose a herding of sheep with the masses of human workers emerging from a subway station, Chaplin announces the film as a statement on the industrial age, which strips mankind of its humanity before depositing them penniless on the street. I don’t think Modern Times gets any better than this first section, in which The Tramp is logging time as an assembly line drone in a factory that has no discernable product. It’s a masterstroke both in conception and production design to construct this massive factory that exists entirely in the abstract—all pulleys and wheels and giant gears, in the Metropolis mode, supervised by an all-seeing CEO and operated by laborers who are often pitted against each other.

For The Tramp, the job is to tighten two bolts on the assembly line with a wrench in each hand. We never see how this small piece of work might figure into a larger construction, only that those bolts must be tightened efficiently, especially as the big boss keeps ordering the line to go faster and faster. This brilliant comic sequence seems to have inspired one of I Love Lucy’s most famous bits, when Lucy and Ethel get a job at the chocolate factory and struggle to keep up. But Chaplin takes it further by giving The Tramp a sort of repetitive stress disorder where his wrenching arms keep moving around even when he’s not on the line. And if he does happen to have those wrenches still in his hands, he seeks to tighten anything that looks like a bolt—the buttons on a lady’s skirt, for example, or a co-worker’s nipples. It’s unmissable as commentary, but still scores big time as comedy.

Meanwhile, the decisions at this factory are being made by a CEO who’s shown reading the funny papers and monitoring his work staff through multiple cameras and screens, including one in the bathroom, where he yells at The Tramp to stop slacking and get back to the line. As you note, cinema was well into the sound era when Modern Times was produced, and it’s certainly notable to see where Chaplin takes advantage of sound in an otherwise silent comedy. Put simply here: The boss has a voice and his workers do not. He barks orders like “Section Five, more speed!” from his office and a beefy, shirtless level-puller out of Metropolis makes it happen, leaving The Tramp and others to suffer in silence.

The opening section also has one of the film’s funniest bits, as “The Mechanical Salesman,” Mr. J. Willicombe Billows, introduces the Billows Feeding Machine, which will allow workers to continue to be productive when they’re on their lunch break. It’s a slight disappointment, frankly, that we don’t see The Tramp having to work the wrenches while being force-fed his lunch, but it’s still incredibly funny to see this malfunctioning gizmo splash soup in his face and assault his teeth with the “double knee-action corn feeder.” I wrote earlier about the Modern Times influence on I Love Lucy, and here you see the origins of a film like Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle, which features a wholly automated house that’s constantly backfiring on our hero.

As social commentary, it’s hard to miss Chaplin’s intent when The Tramp slides into one of the great factory machines and literally gets grinded up in the gears of capitalism. Though The Tramp gets arrested later for inadvertently leading a communist protest, the role and rights of the common worker are central to the politics of Modern Times, which frames The Great Depression as a broken promise made to ordinary people who took this grim industrial labor and were deposited without anything to show for it. Granted, The Tramp isn’t winning any Employee of the Month plaques, but to see him kicked around from job to job (and from jail stint to jail stint) underlines the hand-to-mouth instability of the system.

Does Modern Times get any better than this first section, Keith? I’m not sure that it does, but there’s so much here to treasure, including Paulette Goddard as The Gamine. What do you make of her contribution to the film? And of the life she and The Tramp imagine for themselves?

Keith: I like Goddard a lot in the movie, though Chaplin’s camera loves her so much it takes an imaginative leap to think of her as a street urchin. That’s not to undersell Goddard’s comic talents or what The Gamine’s indomitable spirit brings to the film. It’s The Gamine that kicks off one of my favorite sequences in the film, the one you reference above: the fantasy of settling down into a nice, prosperous life, complete with a cow who wanders by to offer milk. I love it both for the snapshot it offers of the American Dream circa 1936 and for what it says about these characters, who are so far removed from the life they’re imagining for themselves that they can’t quite get the details right.

For some of the same time-traveling reasons I love their vision of bungalow life, I appreciate the sequence set in a department store. We’ll get to the inspired comic moments in a second, but I enjoy staring at the shelves and displays to see what’s on offer (which includes a stuffed Mickey Mouse that gets a quick moment in the spotlight). OK, as for the comedy, the roller-skating on the edge of the ledge is a highlight. It also makes my heart catch in my throat every time, even though I know Chaplin was never in danger while filming it. The robbery scene also provides one of Modern Times’ most memorable and thematically on-point moments. When one of would-be thieves recognizes The Tramp, he tells him, “We ain’t burglars — we’re hungry.” It’s a thin line that separates one from the other, as many learned directly during the Great Depression.

Wanting to get a sense of the environment in which this film was released, I dug up an old article from gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky, written before the film’s release, and before Skolksy had seen it, headlined “In Defense of Chaplin.” Some choice quotes:

[blockquote]

“There are many who believe that Charlie Chaplin is dated, and they expect the flicker, ironically titled, Modern Times, to prove it. It is five years since Chaplin released a picture; during that time there hasn’t been one silent feature. [...] Today a silent flicker is a relic, the method of acting for them is considered obsolete [...] A new generation has grown up that does not know the Chaplin of the screen. They may wonder if their fathers were too hasty in proclaiming Chaplin a genius.”

[end blockquote]

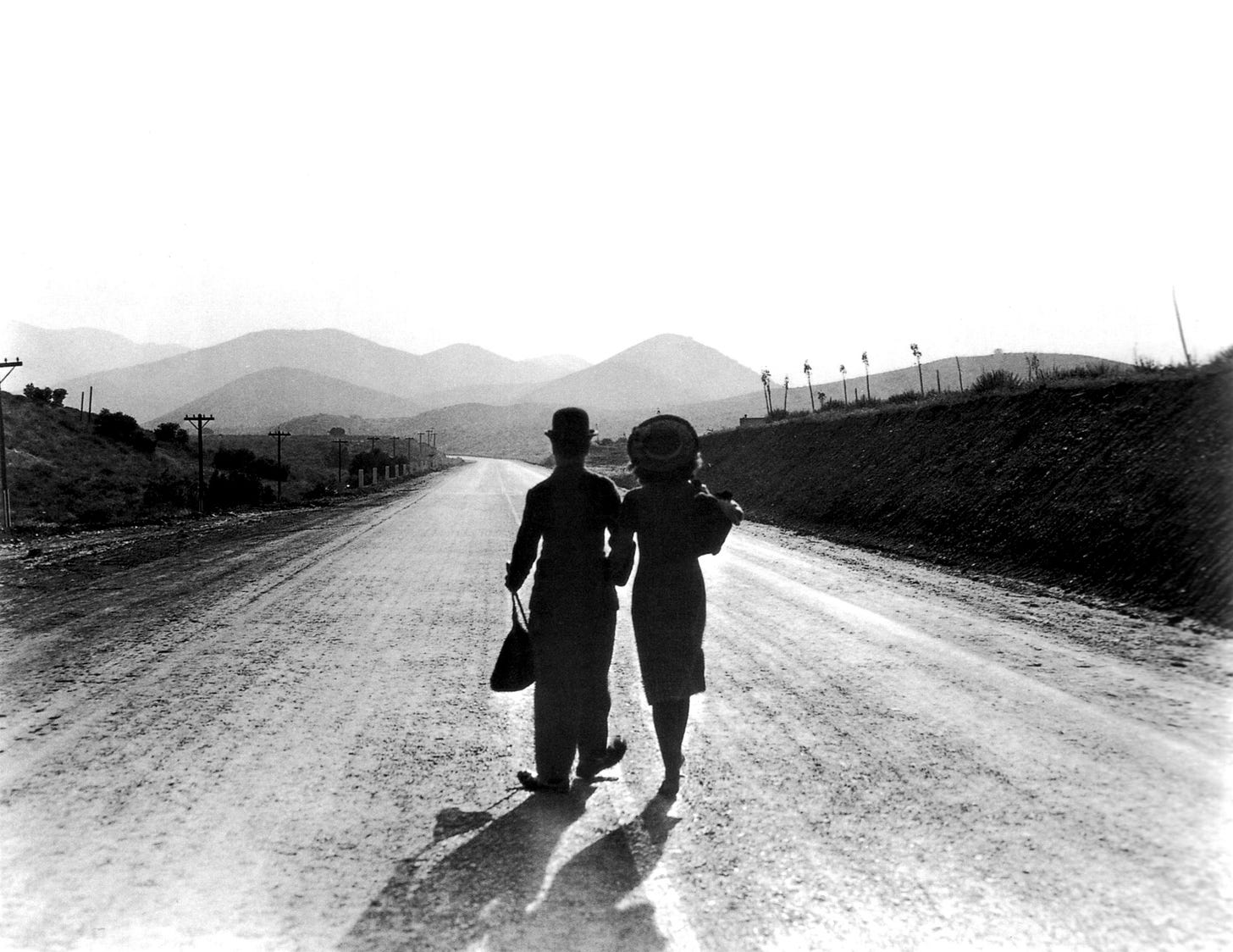

Parts of Modern Times find Chaplin nodding to contemporary tastes. The soundtrack features sound effects throughout and though we never hear The Tramp speak, we do hear him sing a nonsense song while working as a waiter. The film would become a critical and commercial success, but this would be the end of the line for Chaplin as a silent filmmaker, and for The Tramp (as much as Chaplin’s character in The Great Dictator resembles The Tramp, enough differences set them apart to make them distinct). I wonder if audiences of the time saw reminders of what had been lost with the end of the silents? The way Chaplin mimes The Tramp’s surprise and delight after accidentally getting high on cocaine, for instance, needs no dialogue, nor does the final scene of The Tramp and The Gamine walking into the sunset.

Scott, what did you think of the film’s use of sound, particularly the song? Chaplin otherwise makes no concessions to the taste of the times, using intertitles, shooting at 18fps, and using a lot of long takes. And what do you make of the ending and how it connects to all the social commentary that precedes it?

Scott: If Chaplin had really wanted to dig in his heels, then Modern Times might have been wholly silent, as if it were made during the era where sound was not technically possible. That’s not the case, obviously, so Chaplin’s selective use of sound becomes a creative weapon, akin to techniques like a great filmmaker’s use of on- and off-screen space. He may use intertitles and shoot at a lower frame rate, but you do sit up in your chair a bit when he deploys sound because it’s unexpected and pointed.

I already mentioned how you can hear the factory boss speak in the opening section, barking orders through various screens to increase production and keep his workers from spending too much time off the clock. It’s a simple expression of the factory hierarchy: The boss gets to speak and his employees don’t have the power. To extend the point even further, it seems notable that Chaplin emphasizes the sound effects on the machines, too, that take precedence over the men who operate them. Technology was as much a threat then as it would become when automation would take people’s jobs in the future. (The bolt-turning that The Tramp has to do all day is a repetitive task that’s better suited to machines and I think Chaplin makes us aware of that.)

The nonsense song that Chaplin sings at the end, “’Titine, Je cherche a Titine,” has a huge impact for a lot of reasons, not least because we’ve seen The Tramp fail in every job situation and he improvises his way into a success here. But mostly, this is his “Garbo laughs” moment, when an audience conditioned to never hearing Chaplin’s voice can be surprised and delighted by it. It’s also Chaplin re-introducing himself to a new era, despite his obstinance in making a silent comedy when everyone else had been making talkies for years. It’s ironic and absolutely charming that what he’s saying in the song is total gibberish, but the sequence reveals a confidence that he can make a leap that plenty of silent-movie stars couldn’t manage.

Much of Modern Times strings together setpieces that are sometimes barely related to “modern times,” other than referencing the hardships of the Great Depression. What makes it cohere for me is that most of the sequences end with The Tramp getting arrested and going to jail, which provides him a security that he prefers to the uncertainty of a dried-up labor market and a roof over his head. When The Gamine dashes off with a loaf of bread from a bakery, it’s only half-heroic when he steps up and volunteers to take the rap for her. He’s more comfortable when he’s not botching odd jobs on the outside.

Do you have a favorite sequence of The Tramp at work? The obvious standout candidate is the security gig at the department store, which is great for all the reasons you mention, between the fantasy of living it up on every floor (shades of future films, like Dawn of the Dead, making a utopia out of an empty mall) to the skating sequence to the revelation that the burglars are really in the same boat as everyone else. I also like the gag on the dock construction site where The Tramp pulls a wedge and a half-built ship drifts off into the sea. But my vote is for The Tramp returning to factory work with a gig as a mechanic’s assistant, which calls back to the beginning of the film. He knocks into levers, crushes a family heirloom, spills a toolbox into the gears of a machine that spits the tools right back out, and then gets the mechanic himself so squeezed in the works that he has to feed him lunch upside down. Now The Tramp is the Billows Feeding Machine, jamming a celery stalk and egg into the man’s mouth, along with custard pie and hot coffee. An inspired bit of madness.

And yet, Modern Times isn’t a despairing film in the end, which speaks to Chaplin’s sentimental streak perhaps, but also his belief in the redemptive powers of love and the human spirit. The end finds The Tramp and The Gamine in what would seem to be their lowest moment, reduced to hitchhiking on the side of the road with their few possessions wrapped up like hobos. She asks, “What’s the use of trying?” and he’s defiant, saying “Buck up. Never say die. We’ll get along.” In the gorgeous last shot, they’re heading down the road of life together with a smile on their faces. They have each other and that’s a start.

Any final thoughts from you, Keith? It seems like the excitement over Buster Keaton’s work in recent years—and by “recent years,” I’m thinking all the way back to the Kino VHS box that blew many people’s minds (including my own) decades ago—has come at the expense of Chaplin’s reputation. Are we underrating Chaplin now?

Keith: On the subject of favorite bits of work business, I’m not sure you left much for me! So I’ll just throw in a bit of trivia about the film originally including a scene in which The Tramp enlisted in the army and went to war. But because Chaplin exercised such tight control of his films, destroying virtually all unused footage, we’ll never see that, or the alternate ending in which The Gamine becomes a nun.

As for underrating Chaplin, that’s a tough question. I feel like Chaplin has been judged “too sentimental” and compared unfavorably to Keaton for as long as I’ve been reading about movies. I just don’t see it, honestly. I won’t argue that he made sentimental movies, it’s the “too” that trips me up. I’m also not sure that Chaplin was well-served in terms of home media and availability over the years. The first Chaplin I saw was a public domain VHS tape of The Gold Rush, which I loved but wasn’t exactly the best introduction. Criterion’s been doing a pretty good job with the features and, on the Criterion Channel at least, the Mutual shorts, which features the best of his pre-features career. I’ve loved him since first seeing The Gold Rush and I’m happy to see what I think are his two best films made the Sight & Sound 100, just as they did in 2012 and 2002. But they’re the only two in the top 250 and The Gold Rush also made the top 100 in 1992. But I guess, on the whole, Chaplin’s stock remains more or less unchanged over the past few decades, at least on this poll. The Tramp stays in the picture.

That will wrap things up for this installment but we’ll be back soon with another, longer film: Edward Yang’s second entry on the charts, A Brighter Summer Day.

Next: A Brighter Summer Day

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

Just wanted to say that this is a terrific series, so happy to be watching along! I'm pretty slow (just watched Yi Yi - you guys were right, what a picture!), but the movies are great and the writing is just as good. Thanks guys for giving me the excuse to fill in a bunch of blind spots!

Something that always struck me about Goddard in this movie is, for lack of a better term, what a "modern" vibe she has—there's a vibrance and naturalness she exudes that makes the performance feel, to me, very contemporary and less "stagey" compared to many of the era. I've thought this about various actors/performances from the '30s and '40s—one that immediately pops to mind is WIlliam Powell in the Thin Man movies—where their acting style would feel perfectly at home in a modern film.

Anyway, there's my $.02. (Which I would toss to Chaplain and Goddard if I were walking by.)