#78 (tie): 'A Brighter Summer Day': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

With his second appearance on the list, after 'Yi Yi,' director Edward Yang explores Taipei in the early '60s, focusing on a troubled teenager who gets mixed up in a gang war.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

Dir. Edward Yang

Ranking: #78 (tie)

Previous rankings: #88 (2012).

Premise: Unfolding in Taipei in the early ‘60s, Edward Yang’s four-hour epic drama follows Si’r (Chang Chen), a wayward adolescent who lands in night school after failing a test and falls into a culture of juvenile delinquency and turf wars. Though Si’r doesn’t have any particular allegiance to one gang or another, he nonetheless gets caught up in the rivalry between The Little Park Boys and the 217s. While Honey (Lin Hong-ming), the leader of The Little Park Boys, is laying low after killing a 217 member over his girlfriend Ming (Lisa Yang), the charismatic Sly (Hung-Yu Chen) takes over and attempts to ease the conflict with a dance. But when Honey reemerges and the 217s’ leader, Shandong (Alex Yang), pushes him in front of an oncoming car, the tension between the gangs spill over into bloody violence, with Si’r caught in the middle. Meanwhile, back at home, Si’r’s father Xiao (Chang Kuo-chu), a government worker who moved the family from mainland China to Taiwan after the communist revolution in 1949, gets questioned by the secret police for his ties to the party. As Si’r gets romantically involved with Ming, he’s drawn deeper into trouble, with tragic results.

Scott: Keith, let me make a shameful confession up front: A Brighter Summer Day was a tough one for me. We’ve had some tough ones in our Sight & Sound project before—hello, Histoire(s) du Cinéma—and another one coming very soon in Sátántangó, but we already encountered director Edward Yang on this list last May, when we discussed 2000’s Yi Yi, another family epic that was not at all imposing, despite its extensive cast of characters and novelistic approach to storytelling. A Brighter Summer Day is unmistakably similar in style and scope, but there are more significant obstacles to connect to it, at least from my vantage. One of those obstacles is historical: The opening titles help set the stage by noting the millions of mainland Chinese who fled to Taiwan after the communist revolution and the difficult children had in establishing themselves in this new environment, which led some to form street gangs to bolster their strength and sense of identity. That’s important background information, to be sure, but there are cultural nuances here that felt elusive to me. This is a case where the more knowledge you can bring into the film, the more comfortable you’ll end up being.

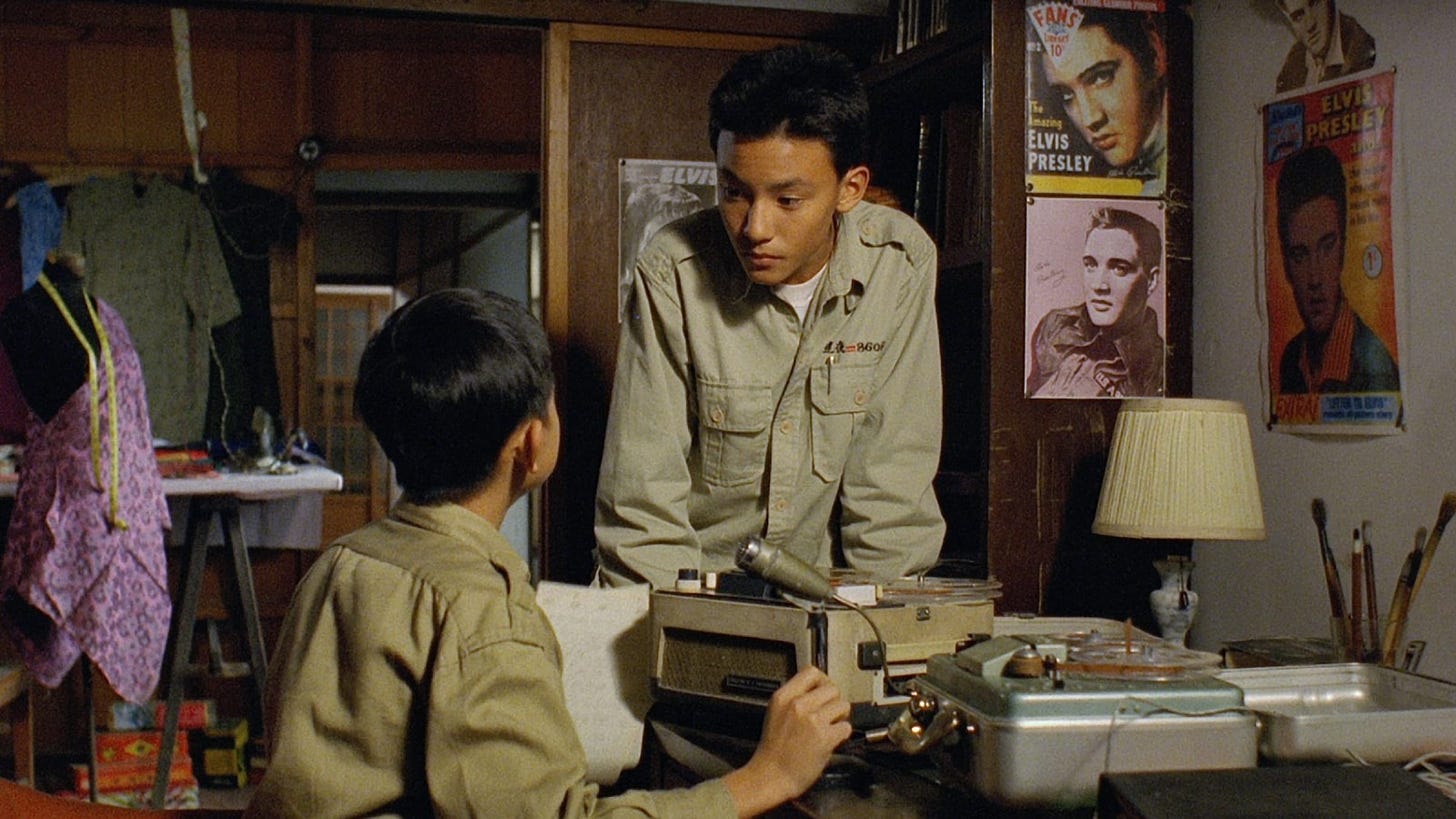

The other obstacle is more on Yang, at least in the way he chooses to enter this world: A Brighter Summer Day has been likened to a larger tradition of films like Mean Streets or I Vitelloni—or Goodfellas, which Yang himself cited as inspiration—where young men of limited means get ensnared in troublemaking gangs, to feel a certain amount of power and a sense of belonging. And it’s not uncommon for the heroes of these movies, like Alberto Sordi’s Fausto in I Vitelloni or Harvey Keitel’s Charlie in Mean Streets, to be passive by nature, willing to conform to an environment that may not ultimately be to his benefit. Yet Si’r, the 14-year-old protagonist of A Brighter Summer Day, is a much tougher nut to crack psychologically, because he’s so thoroughly unformed and impressionable, as many shy, insecure boys his age might be. He doesn’t act out like the heroes of these other films, which often turn their foolishness into rambunctious comedy. That’s not what Yang does here, though his deployment of American popular music, including the Elvis tune (“Are You Lonesome Tonight?”), leads to some of the film’s best moments.

For his part, Si’r just sort of drifts down a dark path, which does hold a cumulative power over a four-hour film that begins with him entering night school and ends with stabbing his girlfriend to death. In between, we can see Si’r lurking more around the edges of conflict, like in the justly celebrated typhoon sequence where the Little Park Boys attack the 217s and Si’r is shown standing toward the back of the group with a small dagger as boys with swords slash and kill their rivals in front of him. But the way Yang shoots A Brighter Summer Day—and the way he shoots Yi Yi, too—is from the marked distance of medium-to-long shots, which doesn’t serve to bring us closer to understanding Si’r’s psychological transformation. It’s not easy for an epic of this scale to be compelling if the person we’re primarily following remains a bit of a question mark, acted on more than taking action.

Am I crazy here, Keith? An embarrassing philistine? Honestly, there are many, many wonderful moments in A Brighter Summer Day and a lot of rich detail to mull over, but I wanted to get these reservations out of the way first. What do you think? Talk me into this movie that so many others consider a masterpiece.

Keith: After I finished this film, I texted you that I kind of wished I’d known going in that the Chinese title translates as The Homicide Incident of the Youth on Guling Street, though I also wonder if the shock I experienced when we get to that homicide might have been why the movie worked for me. (Sorry if we spoiled it for anyone else.) For much of the film I thought I was watching Yang’s I Vitelloni or Mean Streets (which seems closer to the model Yang uses here than Goodfellas). The protagonist of the first gets away. The protagonist of the second doesn’t, but you at least get the sense that he’s earned some insights over the course of the film. Si’r does not. I thought I was watching a coming-of-age story for much of the film. In fact, I found myself thinking while watching the final hour, “This movie is pretty great, but I don’t know if it has anywhere left to go” until developments pushed in a direction I wasn’t expecting.

Even if you don’t know that’s coming, I think Si’r’s opaqueness helps the movie. He is passive and hard to read, which can make the film frustrating at times. But he’s also prone to outbursts that suggest he’s on a downward slope, even if that slope sometimes plateaus for stretches. As the film opens, his father expresses fears he’ll turn bad. In some ways it’s a circular film, ending with that fear coming true as, again, the names of honored scholars being read on the radio as they were in the opening. He’s a protagonist who could go either way—consider the scene where he contemplates hitting the drunken shopkeeper with a brick then saves him instead—until ultimately making an irreversible choice.

This is my first time with A Brighter Summer Day. (I’d wanted to watch it for years but never got to it). It’s not what I expected despite, as you say, sharing a lot of stylistic qualities with Yi Yi (a favorite film I’ve watched several times). The staging and composition, the flow of action, the investment in a sprawling cast of characters, and the lyrical editing choices all reminded me of Yi Yi, but the tone is jarringly different. If the Taipei of Yi Yi is akin to the Dublin of Ulysses — a microcosm of human existence but also a highly detailed time and place — the Taipei of A Brighter Summer Day is a malevolent trap. A military-run government (Taiwan would be under martial law until 1987, just four years before the film’s release) presses down and oppresses those with less power from above while crime and corruption pull down from below. In that respect, you know what movie it reminded me of in that respect: Boyz N The Hood, which came out the same year. Escape is, if not impossible, highly unlikely.

And though Si’r doesn’t do much to earn our sympathies, it’s still sad to watch his downfall. So I wouldn’t say this film was “tough” for me. (Though, boy, a film in which many of the characters wear school uniforms and are only occasionally seen in close-up can make it hard to keep track of who’s who, can’t it?) And I think a second viewing might confirm it as a masterpiece. Knowing where it was heading will probably make me watch it differently. You had seen this before, though. Did that change things? Also, let’s get into the Yang-ness of it all: the period details, the changing relationships between characters, and all the other stuff mentioned above. What about the film worked best for you? I’ll throw out the concert scene in which Si’r’s buddy Cat takes the mic and delivers a rock and roll song in a beautiful boy soprano voice. The camera’s precisely where it’s supposed to be to capture the beauty and the bizarreness of the moment. Sometimes you can feel a master behind the camera, can’t you?

Scott: No doubt. The scenes of Cat singing in that angelic voice are so startling and beautiful, and I love the specificity of that obsession, of translating American pop songs for performances and recordings. It’s moments like those when the memoir-like qualities of A Brighter Summer Day really shine, because so much effort has been put into drawing out these small details. Even the family radio has its own minor dramatic arc, as an important conduit of entertainment and information that goes through various states of disrepair. The music in A Brighter Summer Day—and the white t-shirt with rolled up sleeves that Cat and others are often wearing—gives the impression of American influence in Taiwan at the time, as the island seethes with tension between East and West, Communist and anti-Communist forces, and suspicion between residents and the influx of newcomers from mainland China.

How did A Brighter Summer Day play on second viewing, you ask? I was fortunate enough to get an invitation to see a 35mm print probably 20 years ago, when no Yang films outside Yi Yi were available to see that easily. But I was surprised by how little came back to me beyond the general scope and tone of the film, which to me is telling. Yang’s approach to shooting the film through a lot of medium-to-long shots winds up sacrificing some character psychology and intimacy in favor of the larger context of Taipei during this period. That said, I think you make a good argument about why Si’r’s shocking action toward the end of the film is the culmination of a lot of smaller suggestions of where he might be headed. He’s a quiet, bookish boy like his father, but he’s a failure at school. He has more connections to the Little Park Gang than the 217s, but I don’t think we can say it brings him any feeling of strength or belonging as it might for other boys who have come to Taipei from the mainland. And, like a lot of adolescents, he struggles to process his emotions about girls, which triggers something in him when his relationship with Ming goes awry. It all makes sense, but for a four-hour epic to have such a passive center is a stiff challenge for viewers—or at least this viewer.

I was extremely moved, however, by the plight of Si’r’s father in the film’s second half. Here’s a career government worker, the opposite of a rabble-rouser, who’s suddenly whisked away from his home at night for a lengthy interrogation session that leads nowhere, yet ends in a demotion. His powerlessness is terrifying, and it’s made more so by Yang’s approach to his removal and his questioning, which makes it all seem so inevitable, even for a man who seems to do everything possible to escape notice. There are many memorable shots in the film, but the sequence where Si’r’s mother spots her husband eating alone at a food stall after his interrogation and before his return home is just so crushingly sad. Then when he does come home and some friction arises over how he might have come under suspicion, he breaks down. “We only have each other now,” he tells her. “If you’re not afraid, I won’t be.”

That feeling of alienation within a family is what connected this movie most to Yi Yi for me. The scene where Si’r’s parents argue and then have this emotional outpouring above is the rare example of family intimacy in a film where everyone seems disconnected, particularly when it comes to Si’r himself, who tends to retreat to a bed that’s literally tucked into what looks like a cabinet space. Exchanges between Si’r and his father over school seem strained, like when the boy finally gets expelled from school and endeavors to explain, none too convincingly, that he’ll be just fine. You can’t escape the overall sense that Si’r and his family never feel like they belong in this place, that they’re permanently strangers and second-class citizens and that the future doesn’t seem to offer any hope that this might change. From the father’s perspective, you at least hope that your children, the younger generation, will be able to find their way, but as you say, Si’r is on a downward trajectory from the start.

So what were the standout scenes, shots, or sequences for you, Keith? I loved that the school sits right next to an open production studio, where the kids can sneak in and watch the action from the rafters. It’s the type of place where these troubled young people can escape or even dream of a more glamorous life, like when Ming scores an audition and cries on cue. The typhoon sequence is the film’s major centerpiece, of course, and that’s exceptionally well-done, with the power going in and out, and the young gang members flashing blades in their raingear. For the typhoon assault to take place on the same night that Si’r’s father is dragged away by the secret police is a major gearshift moment that takes us to the second half of the movie, which is a little more internal and family-oriented than the first. What will you remember from this one?

Keith: I’m going to steal a moment used in Paul Dano’s appreciation of the film found on the Criterion Channel to illustrate Yang’s gift for composition: the scene where the kids gather outside the concert venue and pause because the national anthem is playing. It’s a striking moment even before the camera pans to an opening in the crowd at the foot of the steps where Honey makes his return wearing a naval uniform. It’s perfect but it also looks effortless, as if Yang’s camera just happened to catch life as it unfolded at that moment. Another visually striking moment: the horror movie-like emergence of the basketball from the shadows.

As unreadable as Si’r can be, other characters are not. I’m thinking again of Honey and the way he recounts all the books he read during his exile, including that Russian one about the guy who wanted to assassinate Napoleon. What was it called? Oh yeah, War and Peace. Honey has a romantic side and he sees himself in the tradition of tragic heroes and, perhaps knowing he’s near the end, lets Si’r know he should date Ming. Honey has a clear-eyed view of the world but he’s all wrong: He won’t die heroically, he doesn’t know that Ming has been untrue, and he’s a poor judge of character if he thinks Si’r as a nice, safe guy. Honey has limited screen time but he makes a deep impression.

Another scene that will undoubtedly stick with me: Yang plays the humiliation of Si’r’s father in excruciating detail. His interrogator is a sadist, even if he never physically abuses him. The inquiry will blow up the father’s life, though he knows nothing and the authorities know he knows nothing. But as he walks through the facility being used for questioning, he gets a glimpse of someone being questioned while sitting atop a block of ice. It’s a moment that says a lot about what the film isn’t showing (or at least not much) in its depiction of Taipei’s paranoia and repression. In a way, the whole movie’s like that, offering short visits to the home of Si’r’s wealthy friend or the movie studio that establish its story as part of a wider world.

Scott, has all this discussion moved your opinion of the film others regard as Yang’s masterpiece? I still prefer Yi Yi, but I found this quite powerful. It’s a film I’d love to revisit, preferably on the big screen. I suspect my knowledge of where it’s headed would deepen my appreciation and the bigger canvas would allow more details to emerge.

Scott: You know what? Your defense of the film has been very persuasive. I greatly prefer Yi Yi, too, but I’m much more willing now to consider that an indicator of my own limitations than any shortcomings on Yang’s part. The urban alienation and life experiences affecting the contemporary Taipei family in Yi Yi is simply more universal than A Brighter Summer Day, which is unmistakably the work of the same director, but represents a stiffer challenge to Westerners like myself. I’m generally not the type of person who likes to encourage people to familiarize themselves with a film’s historical context before seeing it, but it’s helpful and enriching to do so in this case. It’s also helpful to read Tony Rayns and the late David Bordwell and other experts to get more perspective on Yang’s achievement here.

That said, many of the images you describe will stay with me. And while the political and cultural circumstances that torment Si’r and his family may escape those who aren’t intimately familiar with them, we can recognize the pain of moving to a place where you don’t feel like you belong—in this case, a family that’s in permanent exile from a home that no longer exists for them. A Brighter Summer Day is a title that slightly mangles a lyric from Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?,” but nonetheless seems perfectly evocative. “Does your memory stray to a bright summer day?” For these characters, surely it does.

Next: Sunset Boulevard (1950)

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

Oh boy, could I ever relate to this: "an indicator of my own limitations than any shortcomings on Yang’s part". Not about Yang for me, but it's a question I often ponder when watching Tarkovsky or Antonioni, whose films I just can't seem to get.

This one's on my to-watch list. I read this hoping it would make it seem more inviting, but Scott's experience makes me worry! I'll read up on the context a bit in advance. I remember wishing I'd done so before watching The Conformist (even though it impressed me mightily nonetheless).

This was very helpful, thanks! And started reading the Brodwell link at the bottom, which also seems very useful.

I watched both this and YI YI for the first time last year, and I also immediately loved YI YI and had a much harder time with this. There’s a definite narrative structure here — I could almost glimpse it by the end — but it’s really

really hard to tease out on a first watch (and very unlike YI YI that way), so the film can feel a bit shapeless I thought. But again, that’s probably more on me than on the film itself and I’m sure the narrative shape of the film is a lot more clear on a second viewing. But it’s four hours long!