#72 (tie): 'L’Avventura': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Michelangelo Antonioni's 1960 breakthrough earned jeers and praise in its day. It's lost none of its power to unsettle.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

L’Avventura (1960)

Dir. Michelangelo Antonioni

Ranking: #72 (tie)

Previous rankings: #21 (tie, 2012), #22 (2002), #16 (tie, 1992) #7 (1982), #5 (1972), #2 (1962)

Premise: Accompanied by her friend Claudia (Monica Vitti), Anna (Lea Massari), the privileged daughter of an Italian politician, sets off on a Mediterranean yachting vacation with her boyfriend Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), with whom she’s reuniting after an extended time apart due to Sandro’s job. After the expedition docks on an island, Anna disappears. When a search comes to nothing, Sandro and Claudia pair up to follow a trail of unpromising clues across Sicily. All the while, the two develop an undeniable attraction that they act upon, seemingly starting a serious relationship. Ultimately, however, the situation reveals itself as more complicated.

Keith: Here is my confession: I had a hard time connecting to Antonioni for a long time. I watched Blowup first. It was the easiest to find and I knew a little of what to expect because there’s an extended parody of it in Mel Brooks’ High Anxiety. (And, come to think of it, I probably saw High Anxiety before any of the Hitchcock movies it parodied, too.) I was in high school then and I didn’t know what to make of it, but I was left a bit cold years later when I watched it in grad school and should have been better equipped to understand what it was doing. (It was the rare film made part of the English curriculum.) Fast forward a few more years when I watched L’Avventura for the first time and this, too, baffled me. It’s not that I didn’t like it. Just on a visual level, it’s hard not to admire. But I didn’t really understand what it was up to. It wasn’t until I saw Antonioni’s 1975 film The Passenger that I got it. Its story, about a character who swaps identities with a dead man and discovers just how untethered he was to the world even before making the switch, felt like a key that unlocked the rest. I had really been going about it the wrong way. Though working decades later, Antonioni had as much, if not more, in common with some of the modernist literature I loved, like D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love and Ford Maddox Ford’s The Good Soldier, than his filmmaking contemporaries. He was depicting stories of lost souls wandering a world in which the old ways of finding meaning had become hollow and nothing yet had taken their place.

Take the opening scene, for instance, on the hills overlooking Rome. Anna, our seeming protagonist, talks to her father while standing on a path that leads to a view of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. Behind her are a bunch of interchangeable apartment buildings that will soon fill the space. The continued existence of the glories of the past mock the present. Later we meet Sandro, an architect who’s gotten rich doing unsatisfying work. He envies the freedom of those who made grand structures with an understanding of “theatrical effect” while he performs estimates and caters to the whims of tasteless clines. “Back then,” he laments, “they built for the ages. But today, how long do things last? Ten, 20 years, and then?”

But is he only talking about buildings? Nothing in L’Avventura seems built to last for long. Sandro and Claudia fall in love, make plans to marry, then watch their relationship fall apart over the course of a few days. Their friends’ relationships feel just as frivolous. They pass by churches but never think to seek meaning inside. Even sorrow fades quickly. The disappearance of Anna is surely the most remarkable event in either of their lives, robbing Claudia and Sandro, respectively, of a best friend and lover. But their search loses any search of urgency not long after it starts until, by film’s end, Anna’s been all but forgotten, another untethered life that simply floated away with no apparent meaning.

A bit more context before pushing forward: L’Avventura won the Jury Prize at Cannes in 1960 after a premiere screening in which it was greeted with jeers and laughter. Two years later, the 1962 edition of the Sight & Sound poll placed it behind only Citizen Kane on the list of greatest films of all time. That’s an extraordinary reversal of fortune. Yet it keeps sliding down each new version of the list. The only other Antonioni films in the top 250 are L’eclisse and Red Desert. Blowup is nowhere to be found.

Scott, what do you make of L’Avventura’s near-instant canonization after its rock debut? Should we conclude that Antonioni’s influence has waned over the decades? And what is your own relationship with Antonioni and this film? Did it also take you a while to lock into what he was doing?

Scott: This movie is quite a faller, isn’t it? One of the fascinating things about the Sight & Sound poll is watching certain films and filmmakers fall in and out of favor with critics. Sometimes this can be chalked up to something as simple as availability: If a movie is hard to watch, naturally a young generation of critics may not have rallied around it or, conversely, if a film gets a restoration and re-release or gets championed by prominent filmmakers or tastemakers, maybe it makes the rise. But there’s never really been a time when L’Avventura hasn’t been a canonical classic for anyone to see, and it’s the rarest of rare examples of a film that was almost instantly coronated yet has seen its fortune tumble, especially in the 2022 poll. Does this reflect Antonioni and the modernists’ waning impact or, perhaps, a global cinematic landscape so profoundly impacted by L’Avventura that there are simply more choices to draw away votes?

I lean toward the latter. You describe the infamous premiere at Cannes, where the film was booed and mocked by the audience yet embraced so fervently afterwards that it came away with a Jury Prize and went on to become an international sensation. I’m reminded a little of Pauline Kael’s review of Last Tango in Paris, where she likened the film’s New York Film Festival debut to the night in 1913 when Le Sacre du Printemps thrilled and scandalized the public with the “primitive force” and “thrusting, jabbing eroticism” that she associates with Bernardo Bertolucci’s film. For L’Avventura to debut on the Sight & Sound list two years later at #2 is almost inconceivable now: There would be no possible way, in my view, for modern critics to achieve that kind of consensus around a new film, mainly because I lack the imagination to see cinema itself could be changed in quite the same way. As it happens, L’Avventura is far from my favorite Antonioni movie, but if you put yourself in the mindset of a cinephile in 1960, you could understand it as revolutionary in its effort to turn a slower, more contemplative cinema into less a narrative engine than a landscape of the soul.

My journey with Antonioni also began with Blowup, which I admired (and admire) as a demonstration of our capacity for self-deception, particularly as it relates to images and the (perhaps false) stories we tell ourselves around them. It also happened to influence two of my all-time favorite films, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation and Brian De Palma’s Blow Out, the latter of which was on my own Sight & Sound ballot for 2022. I’ve admired many of Antonioni’s other work over the years—I wrote an appreciation of his maligned American film Zabriskie Point for The Dissolve—but the one that has most enraptured me is La Notte, which he and Vitti made only one year after L’Avventura, but explores many of the same themes with a little more elegance and dramatic punch.

But if you put yourself in the mindset of someone first encountering L’Avventura in 1960, you can see what a revelation it might be in totally recalibrating our expectations of what a movie can be. So many elements of it stand out for me, but I have to start with Anna’s disappearance, which is the mystery that ostensibly drives the film, but audaciously fizzles out. Maybe we can think about what happened to her, judging by certain clues, like her making up the story about her brush with a shark in the water or her expressing such discontent over her relationship with Sandro that she has opted to take some dramatic action. But no explanation seems plausible—not an accident nor a deliberate effort to leave—and that’s not really the point anyway. Anna’s boatmates scan the island for her, as do the authorities, and Sandro and Claudia take up the search on the mainland, but Anna’s relevance is eventually limited to the diminishing space she takes up in these character’s consciences. Sandro seems to get over it quickly, given how swiftly he turns to Claudia for affection, though Claudia is more conflicted. You never know, from one scene to another, which direction Sandro and Claudia’s relationship is going to turn. I suppose that’s where Anna has taken residence.

What do you think Antonioni is trying to say about Anna’s disappearance? Is L’Avventura merely an act of deconstruction where he’s teasing the audience with a mystery and then defying conventional expectations about how (or if) it will be resolved? Is the fact that she’s forgotten a statement on human nature and our capacity to put such things behind us or is it specific to these characters, who themselves are vacuous avatars of privilege and narcissism? I’m not sure where I stand, but there’s always been some gamesmanship on Antonioni’s part in what he chooses to show us and what he deliberately elides. He’s excellent at creating a suggestive mood, however, and making you feel the emptiness that surrounds these characters on a deep, subconscious level. He was a pioneer in crafting the sorts of contemplative, existential spaces that I’ve come to admire from many disciples in many corners of the world.

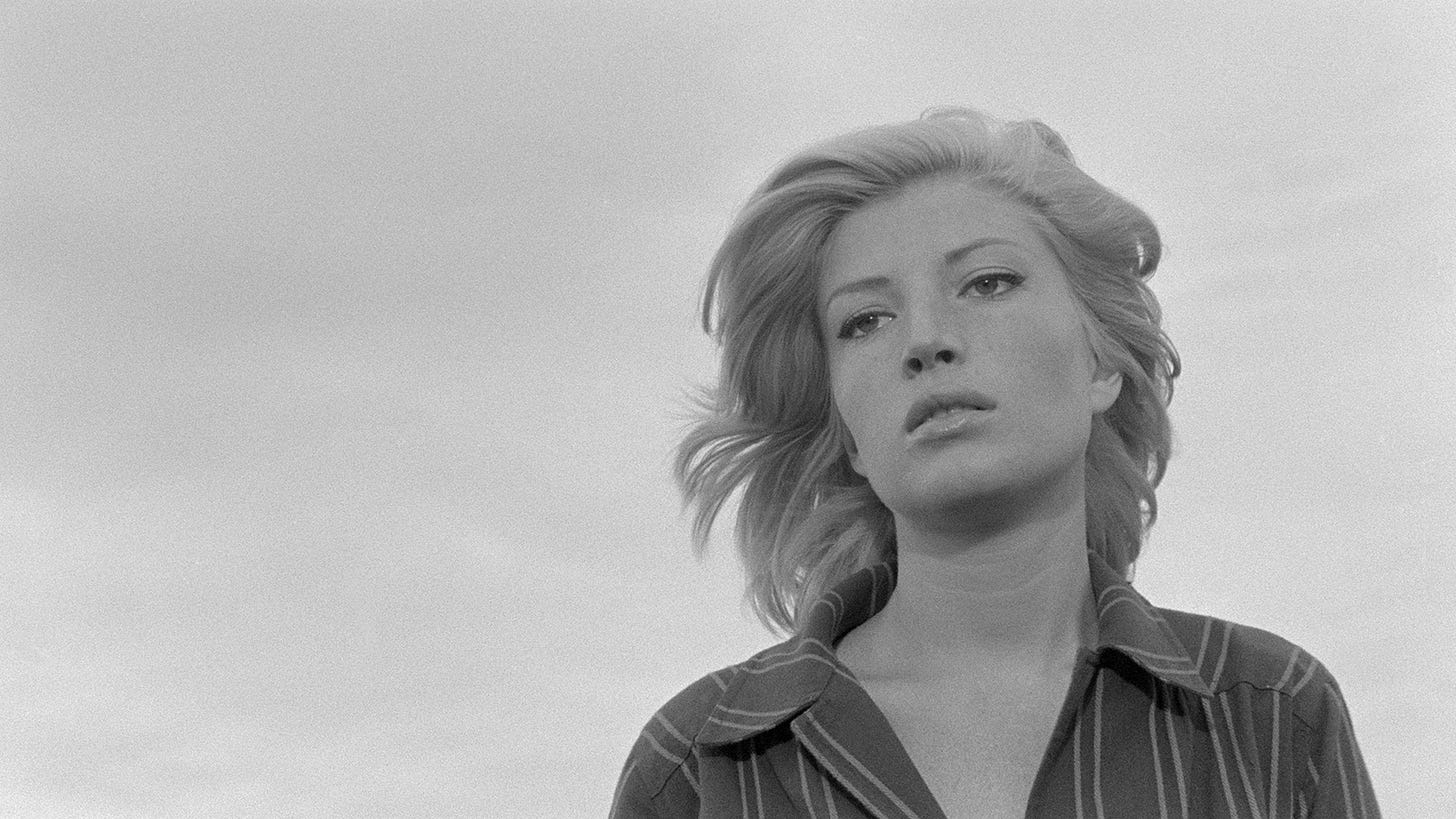

How about that Monica Vitti, eh Keith? I think so much of European art cinema of the ‘60s is owed to women like Vitti and Jean-Luc Godard’s actresses (Jean Seberg, Anna Karina, Brigitte Bardot) who were a new kind of movie star, attractive yet enigmatic, like aliens on earth. We can see a little of that when Vitti’s Claudia is surrounded by leering men in a small town, who recognize an exotic being when they see one. And L’Avventura, like much of Antonioni’s work, has a serious erotic charge, even if it’s not explicit like his future films would be. How much do you imagine that figured into how the film was received? And what do you see as Vitti’s special qualities as a screen presence?

Keith: That scene, of the men staring at Claudia with a mix of amazement and hostility, is the one that always comes first to mind when I think of L’Avventura. Watching it again it reminds me of the scene where the birds gather behind Tippi Hedren in The Birds, although Claudia’s much more aware of the threat. By coincidence, it’s the image used to head Vitti’s 2002 New York Times obituary. Though maybe it’s not that coincidental. I’m not sure which shot better sums up the film: this one or the closing scene image of Claudia and Sandro looking out over the sea, one half of the frame taken up by a featureless wall.

And I think you’re right, if I’m reading you correctly, to suggest the women of ‘60 European art cinema don’t get enough credit. Vitti, Anna Karina, Liv Ullman, and Giuiletta Masina (and probably others I’m forgetting) all get called “muses” to their respective partners, but that’s a vague term that I suspect doesn’t reflect the full extent of their creative partnership. And Vitti’s a striking presence, especially here, because she doesn’t fit the dark-haired, smoky-eyed mold of “glamorous Italian actress from the ‘60s.” Lea Massari, by contrast, does. In one scene, some of the Sicilians mock Claudia’s fair skin and blonde hair. She’s a bit alien even in her own country.

As for the disappearance of Anna, here’s how Vitti answered when pressed (a detail also found in that obituary):

It isn’t important. What is important is that Anna was carrying two books before she disappeared — the Bible and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night. One suggests our concern with morality; the other was a literary experiment in which the heroine disappears halfway through the book and is replaced by another protagonist.

That clears things up, right? I kid, of course, but it does seem like another example of Antonioni providing just enough information to make you feel like you could piece together what’s going on with one or two more telling details. (I’m still hung up on the secret alluded to in Anna’s conversation with her father. Is it personal? Political? Who can say?) I’m sure you’re with me in thinking it’s a richer film for us not knowing, though. The ease with which Anna slips out of the world is scary, but not as disturbing as the swiftness with which she leaves the memories of those ostensibly closest to her.

Circling back to the Cannes premiere, the award was given, in the words of the festival, “For the beauty of its images, and for seeking to create a new film language.” Where do you hear that language spoken today? You’ve alluded to Antonioni influencing The Conversation and Blow Out, which seem to be the most mainstream (relatively speaking) examples of Antonioni’s influence elsewhere. It’s easier, I think, to see the influence of contemporaries like Godard and other French New Wave filmmakers, whose techniques were absorbed by Hollywood filmmaking pretty quickly and remain present today. (Have you ever seen Love Story? It’s not good, but it’s kind of fascinating to see all those New Wave touches applied to such a treacly product.) Does L’Avventura’s descent down this list suggest it’s a dying language?

We should also talk a bit about the title, which translates as “the adventure” but the “l’avventura” is also used as a synonym for “spree” in Italian. Either use seems ironic, but is there anything else going on? Also, am I off in thinking it’s as easy to read this film as moralistic as it is a critique of outdated morality? Are these contemporary characters suffering from too much freedom and too much disconnection from tradition? Or are the guilt and ennui they experience the result of the continuing influence of an oppressive, outdated moral system they’re reminded of every time they turn a corner and see a church or a religious statue? The reading I like best is one that allows for both feelings to exist at the same time in a kind of quantum state. I don’t think Antonioni made films that could be reduced to either/or propositions so easily..

Scott: Forgive me a little for continuing my obsession over the l’avventura that L’Avventura has undergone on the Sight & Sound list, because I think it’s so revealing about where cinema was in 1960 (and 1962, when the film debuted with a shot on the list) and where it would go. The phrase “seeking to create a new film language” is so striking and, I think, completely true. Can you think of any films pre-1960 that suggest a sea change quite as much as L’Avventura? I’m sure a list of predecessors could be drawn up, because something doesn’t come from nothing, save maybe the Big Bang, but Antonioni is taking an audacious narrative risk by allowing this missing-person mystery to vaporize and an even more substantial aesthetic risk by allowing the tone, the composition, and the topographical and architectural backdrop to do the heavy lifting. The film is the canonical “booed at Cannes” classic: How else do you expect an audience to react to something they’ve never seen before?

I think you’re right, to an extent, that the French New Wave sucked up a lot of the modernists’ oxygen in terms of influence, but I’d also give a great deal of credit to Antonioni and L’Avventura for seeding the international film scene so profoundly that films like L’Avventura have found their own set of champions. As I mentioned in the last missive, Antonioni certainly wasn’t done making great movies, but if you look at the very top of the Sight & Sound list, now occupied by Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, you have a “seeking to create a new film language” candidate that’s in the Antonioni sphere of what the kids call “slow cinema.” I can remember seeing the Akerman film for the first time and having the thought, “Wow, movies can do that.”

To tie this into the events of the film, I have to go back to my favorite idea from Abbas Kiarostami, who talked about “a type of cinema that gives greater possibilities and time to its audience.” He called it a “half-created cinema” that “attains completion through the creative spirit of the audience.” We’re so used to movies ending in periods and exclamation points, but Antonioni, like Kiarostami later, allowed for question marks. That obviously includes Anna’s unsolved disappearance—and, just as famously in Antonioni’s work, what the pictures reveal in Blowup—but we’re also left to guess, as you suggest, about what Antonioni wants us to feel about the morality of these characters and what their disconnection from a more modern, changing Italy says about them or the country. It’s funny that you point out the two books Anna is holding, which are definitely blaring signposts waiting for our interpretation, yet we’re still puzzling over it.

The characters themselves are in a state of puzzlement, too, starting with Anna, who runs so hot-and-cold with her boyfriend Sandro that they steal away from Claudia to make love shortly after getting together yet she complains about their long-distance relationship. (“The idea of losing you makes me want to die,” she tells Sandro. “Yet I don’t feel you anymore.”) When Anna goes away and a romance develops between Sandro and Claudia, there are again moments when they are passionate with each other followed in short order by scenes where Claudia’s guilt over betraying her friend overwhelms her. Maybe there’s something here about how people handle loss, how grief and guilt ebbs and flows. But I think Antonioni is hinting at a larger adriftness gripping his characters, who seem as untethered as their yacht tossed around at sea.

Alienation is the big theme in L’Avventura, which is an “adventure” to nowhere but the yawning vacancy that has opened up in the souls of the leisure class. I’ve seen interpretations of the film as Antonioni’s attempt to express the “lost generation” of young people after World War II, who may be driven by impulse, as Sandro and the two main women are here, but are disconnected from tradition and from religion—which, in one unforgettable sequence in a deserted town in Sicily, is reflected in the echoes of their voices through an abandoned church. Roger Ebert interviewed Antonioni in 1969 when he was preparing the shoot Zabriskie Point in America, and he got a great quote from the director about how little even he knows about his own work:

“I never discuss the plots of my films. I never release a synopsis before I begin shooting. How could I? Until the film is edited, I have no idea myself what it will be about. And perhaps not even then. Perhaps the film will only be a mood, or a statement about a style of life. Perhaps it has no plot at all, in the way you use the word.

Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps, Keith. Perhaps Antonioni is due for a comeback in our vibes-obsessed culture, though we emphatically do not live in a time when a studio like MGM might fork over a budget for Zabriskie Point without having any idea what its famously enigmatic director might do with it. I guess my last question to you is: If we’re talking about Antonioni as a filmmaker comfortable with ambiguity, what’s deliberate and intentional in a work like L’Avventura? This film is very beautifully composed and does fulfill the title promise of giving us a generous look at multiple parts of the country. What does he want us to see?

Keith: That’s a great quote from Antonioni, but I also think it’s kind of… is there a polite word for bullshit? His compositions, camera movements, and editing rhythms all suggest intense deliberation. Every detail in every frame seems to matter. Or, at the very least, he makes films where enough details prove significant — to his themes, if not the vagaries of the narrative — that it feels like every detail has significance. The late, great David Bordwell has talked about how Antonioni intentionally blocks our access to his characters’ inner lives, both by withholding backstory and by staging dialogue exchanges so we often don’t see the reactions of those being addressed. (Take the scene of Claudia and Anna talking on the boat where we see only their backs.) That leaves everything else to fill in the blanks.

After watching L’Avventura, I watched L’Eclisse, which Antonioni made after L’Avventura and La Notte (they’re often treated as an informal trilogy). That one opens with two lovers talking over the end of a relationship in an apartment filled with books, paintings, objets d'art, and assorted knickknacks. Do any of them matter? The lingering shots seem to suggest so. The film doesn’t supply any answers, but nothing feels accidental or meaningless. I think the short answer to your question is he wants us to see everything.

Is that an answer? I guess that, sort of appropriately, ends this discussion on a question mark, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that L’Avventura debuted the same year as another movie that dispenses with its apparent lead to shocking effect early on: Psycho. Was there something in the air in 1960?

What’s next, you ask? That I can answer definitively: We return to Hiyao Mizoguchi’s Japan, via catbus, for a discussion of My Neighbor Totorro.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

I'm sort of loving, but feel compelled to point out, the auto-correct/typo fun of the director of My Neighbor Totoro, Hayao Miyazaki, appearing here as "Hiyao Mizoguchi." It suggests a sort of hybrid person, part Miyazaki, part Mizoguchi, that Miyazaki would create....

I feel like I say on half these Sight & Sound posts that I'm a middle-to-low-brow movie fan and that I've never heard of half the movies on the 2022 list, and this is one of them (I do know BLOW-UP). It's fascinating to me that a movie I've never heard of was held, in 1962, to be the second-greatest ever made. That seems like...something I should have heard of? Like, even if I hadn't seen it, like something I should have heard *of*? I will seek it out.

Scott and Keith, your primary intention in running this series might be for the enjoyment and edification of the kinds of people who've "heard of famous movies" or whatever, but you're also doing an invaluable service for people like me whose idea of a movie is HOWARD THE DUCK. I thank you for that.