#75 (tie): 'Spirited Away': The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

The first of two Hiyao Miyazaki films on the Sight & Sound list visits a bathhouse for spirits that operates on its own mesmerizing dream logic.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Spirited Away (2001)

Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

Ranking: #75 (tie)

Previous rankings: #72 (2012)

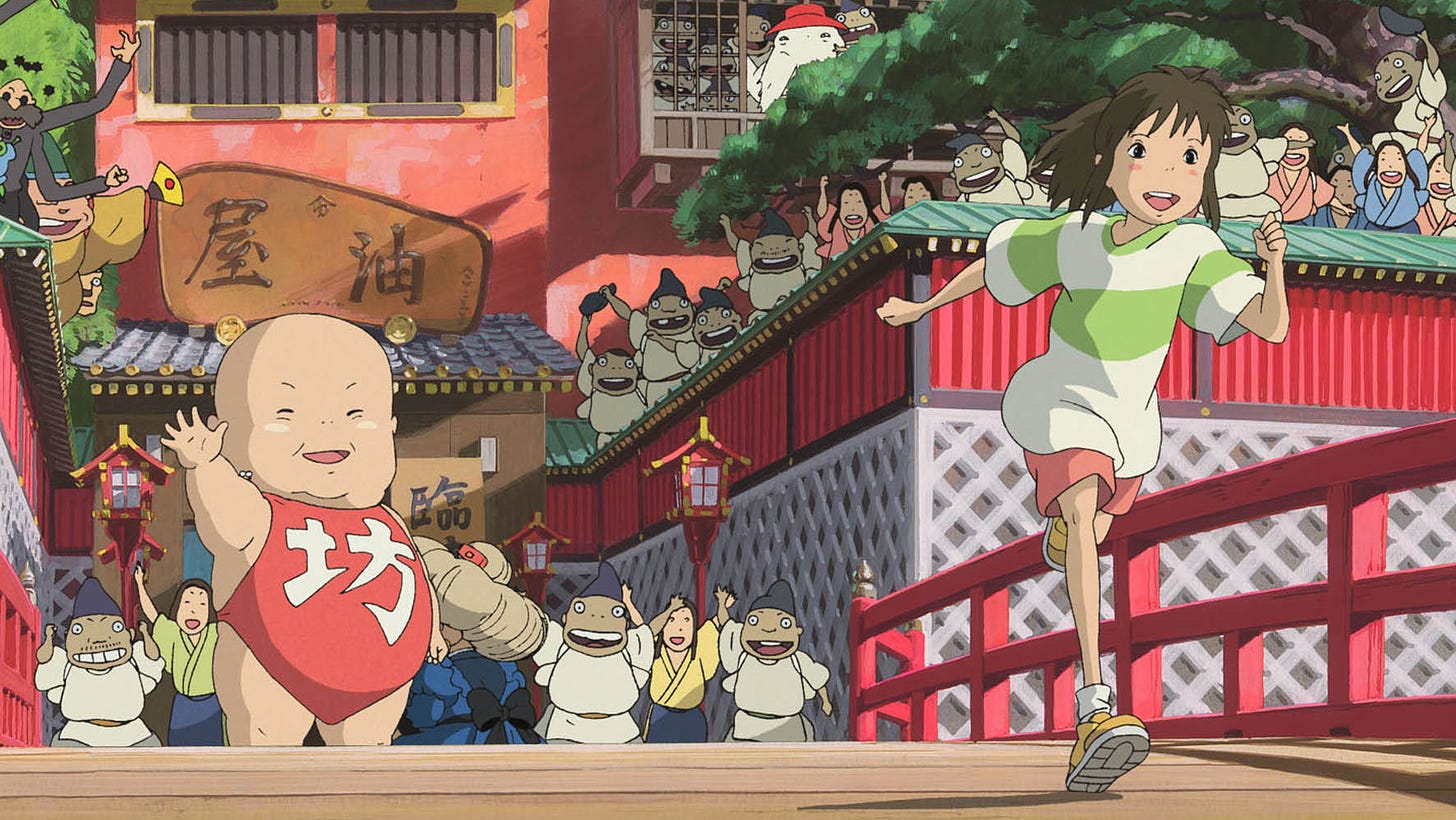

Premise: When 10-year-old Chihiro and her family take a detour en route to their new home somewhere in the Japanese countryside, they stumble on what appears to be the ruins of a failed amusement park. Frightened, Chihiro reluctantly follows them, meets a friendly but mysterious boy named Haku, then discovers her parents have been transformed into pigs and that she’s trapped on the other side of the river, home to a spirit-filled bathhouse. Once there, she takes on a variety of jobs as she meets its inhabitants, including a seemingly benevolent, ghost-like figure she comes to know as No Face and the short-tempered bathhouse boss Yubaba, who renames her Sen. In time, her journey takes her beyond the bounds of the bathhouse on a roundabout journey back home.

Keith: I’ve probably seen Spirited Away more times than any other movie on this list. That’s in part because I love it, but also because I’m the dad to a 21st century kid and, like all responsible movie-loving parents, my wife and I made Miyazaki a fixture when our daughter was growing up. But for as many times as I’ve seen it, I find I often get lost in it. This will echo some thoughts I expressed when we covered Spirited Away on a recent episode of The Next Picture Show, but I almost never remember what happens next when watching this movie. What happens at the beginning and end are clear in my memory, but the rest is a little fuzzy if I haven’t seen the film in a while. Does Chihiro meet the spirit of the polluted river before she sees the big baby, or does that come later? When does Zeniba show up?

If I had to offer a theory as to why—beyond my own mental limitations—it’s that Spirited Away never assumes a familiar narrative shape. It kind of floats from moment to moment and incident to incident following dream logic. Or at least that’s how it seems while watching it. Take a step back and Chihiro’s journey has a progression to it as she moves up the ranks in the bathhouse, becomes defiant instead of scared when dealing with Yubaba, and rescues Haku after first being rescued by him. But for all the work that clearly went into making this beautifully hand-drawn animated movie, it still has the quality of a children’s story made up on the fly. And this happened, then this happened, then this happened.

Miyazaki has said he made this movie for kids of Chihiro’s age and, as much as adults might appreciate it, I think Spirited Away transmits on a wavelength that it’s particularly easy for kids to pick up. This might be an unfair comparison, but I found myself thinking about the gulf between Spirited Away and, say, an Ice Age movie in which Ray Romano’s wooly mammoth goes on about middle-aged problems. Some kids' movies seem to be made by people who’ve never met kids before. Spirited Away plays like the work of a kid who just happened to grow up and grow old.

Not that Miyazaki doesn’t bring plenty of adult concerns to the movie. I brought up the polluted river spirit before in part because I find that scene both haunting and infuriating, stirring some of the same feelings as the opening scenes of WALL-E. You can find distrust and pessimism about the future in many of Miyazaki’s films, particularly regarding the environment and war. I don’t think it’s a coincidence (or particularly subtle) that the unchecked gluttony of Chihiro’s parents is what gets them into the mess to begin with.

But is it entirely a mess? Chihiro’s journey takes her to a place that seems threatening and wondrous in equal measure. She wants to go home, but she has work to do before she goes. But what does she accomplish and what’s the point of her journey? I have some thoughts, but I’d love to hear yours, Scott. Also, has this been a fixture in the Tobias house, too?

Scott: It would be an understatement to say that Spirited Away has become a fixture in our house. Our 16-year-old has made Studio Ghibli such a primary passion in her life that she intends to start an afterschool club around it. We’ll touch on this very soon, since it’s just ahead of Spirited Away at #72, but My Neighbor Totoro was her favorite movie at a very young age, when you don’t expect kids to process anything more sophisticated than Tinkerbell movies or The Backyardigans. What I concluded is similar to what you suggest above, which is that children are able to accept the dream logic of Miyazaki’s work more readily than adults, who might get stuck in a world where nothing makes sense or where it seems like the rules are being made up as you go along. Obviously there are different levels of Miyazaki—Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service are more kid-friendly than, say, The Wind Rises—but you get the point. Let me say up front that I’m hugely grateful for Miyazaki’s core influence on my daughter’s appreciation of storytelling and art. He was the start of a lifelong journey.

Spirited Away is my favorite of Miyazaki’s films, and I think you do well in describing why: That feeling of being adrift on his peculiar narrative wavelength, not sure precisely where you’re going to go even if you’ve seen the film multiple times. There’s also just the astounding beauty of the images, combined with a delicate mix of tones that are keenly attuned to the way Chihiro feels—her fear and wonder about the strange world she’s entered, her delight at the cute creatures she meets, her confidence as she makes decisions and takes actions on behalf of her friends. There may be a dream logic to the way the film unfolds—sure, I guess she has to hold her breath on the bridge to keep from being spotted—but there’s an identifiable emotional coherence that has a real arc and holds everything together.

The very beginning of this film gets me every time, because I have such a personal reaction to it. I grew up in small-town (now medium-town) Perrysburg, Ohio and loved it there, as did my family, and I vividly remember the experience of driving toward I-75 on our way south to a roach-infested apartment in Marietta, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta, where my dad had found a new job. Everyone was heartbroken, and the little red streaks under Chihiro’s eyes brought that back for me. I wasn’t looking forward to going, for one, but the other part of it, which Spirited Away evokes, is a lack of confidence. No matter what happens, Chihiro is not going to be on sure footing for a while, and now her father is plunging headlong into a detour that’s making her feel worse. This odyssey ultimately gets her to a better place.

So what does she accomplish, exactly? It’s interesting to me how much the early scenes darken her understanding of her parents, and of the adult world. She’s appalled by the gluttony of them sidling up to an unmanned food stand and chowing away like the pigs they’re about to become, but the entitlement of it is striking, too. Dad has a credit card, so they don’t need anyone’s permission to help themselves to an all-you-can-eat buffet. You could say that she enters into this situation with a strong sense of right and wrong that contrasts with corrupted grown-ups, both in the spirit world and the real one. She doesn’t grasp for the gold nuggets and food that No Face offers her, and her kindness and care for others becomes an animating force, giving her the courage and strength to help Haku and to brave dangerous situations. I’d say that the experience doesn’t change her so much as reveal who she really is.

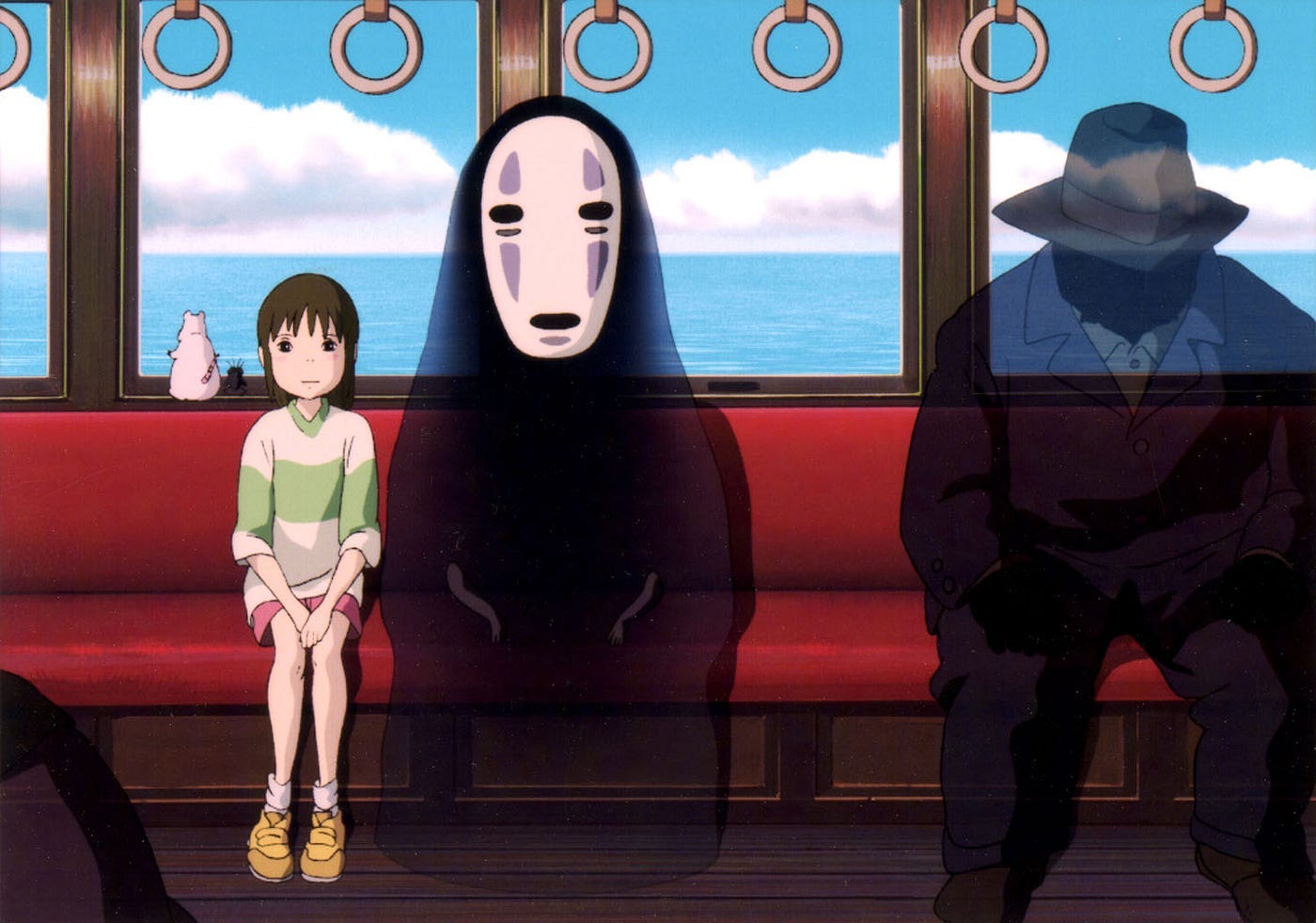

I’m not as articulate on animation as you—whenever we cover animation on The Next Picture Show, I tend to let you and Tasha and Genevieve take up the conversational slack—but I’m also a sentient being capable of responding to the obvious cinematic beauty right in front of my face. Spirited Away is the film where the collaboration between Miyazaki and composer Joe Hisaishi feels most complementary, like there’s a serene harmony between sound and vision. I had first encountered Hisaishi as a composer for Takeshi Kitano’s work and that was a fascinating relationship, too, because Kitano liked to go halfsies between scenes of offbeat, deadpan whimsy and moments of gruesome bloodletting. But you get to the money sequence of Chihiro gliding along on the train across the water and collaboration is just so pure—pretty, a little melancholy, haunting like the ghost story that it is, but still singular. Movie moments are a big part of the Spirited Away experience. What are the ones that grab you, Keith? And what can we say about the other characters in this world and the robust spirit bath–house business?

Keith: I feel like there might be some cultural differences that prevent me from fully understanding the spirit bathhouse, in part because I’m also an Ohio native and thus I blush at the idea of any kind of bathhouse. I also suspect some of those spirits are more recognizable to Japanese eyes. I know, for instance, that dragons tend to be associated with rivers in Japanese folklore, but only now discovered that the Radish Spirit (a favorite) has a connection to a Shinto spirit called the Oshirasama. At some point I should chase down all these references, but I don’t know that not catching all of them has interfered with my enjoyment of Spirited Away. It’s probably helpful to think of the bathhouse being a whimsical notion: See, even supernatural spirits need to tend to their personal grooming! But as far as how the economy of the place works, you got me.

Scott, you’ve already mentioned the train scene and I brought up the polluted river spirit’s bath, both favorites of mine. I also love the moment when Chihiro figures out that Haku is the spirit of the Konaku River and saved her from death when she was younger. It’s great in both the Japanese version and the English dub, though I’ve grown attached to the breathless way Daveigh Chase, as Chihiro, delivers the line, “I think that was you, and your real name is Kohaku River!” If the film has a climax, it’s that moment. But that’s an if. Most of my favorite moments are those spent exploring new corners of the bathhouse, which seems to have been thought through to the smallest detail while remaining completely fanciful. I notice something new each time (like how giddy my guy the Radish Spirit looks when Chihiro outwits Yubaba).

Pinging off your thoughts, Scott, I think if Chihiro isn’t much changed by her experience beyond discovering the confidence to be the good, smart person she already is, I think maybe the spirit world does change for the better after her visit. From the start, Yubaba seems more embittered than evil and her conflict with Zeniba looks quite different when seen from Zeniba’s perspective. I’m not sure everything gets better after Chihiro leaves but, like Oz after Dorothy, I don’t think it goes back to the old order after she leaves. Where I see no change, however, is with Chihiro’s parents, who leave their swinish selves behind with no memory of what their greed turned them into. Perhaps we’re to be left with the sense that any changes to the real-world ills reflected in the spirit world will have to come from Chihiro’s generation.

I don’t want to exhaust our Miyazaki thoughts because, as you noted, we’ve got more to come, and soon. But, though you state above that you don’t have as much comfort with animation as other forms, you and I both lived through this moment in animation history and though they say you never know when you’re in the midst of a golden age, I think we kind of did? Sure, Disney’s hand-drawn animation was starting to wither, but Pixar was turning out instant classics on a regular basis. 2001 produced Shrek, whose influence would prove pernicious in a couple of different respects, but also Waking Life. Beyond Miyazaki, I usually feel as adrift when it comes to anime as you do with animation in general, that industry was thriving, too. The previous year brought Chicken Run. Two years on would bring The Triplets of Belleville. And yet, Spirited Away still kind of towers over all of them, doesn’t it? Any thoughts on why? And any final thoughts before we move onto a movie that might be just as great but surely less magical (no matter what comes next)?

Scott: You’re blowing my mind a little with that last paragraph, because I never thought about the ‘00s as the middle of a golden age for animation, but I certainly do now. I think I was so bummed about computer animation rendering hand-drawn a niche (at least in American studios) that I threw out the baby with the lazily-rendered-sassy-talking-animal bathwater. But between Miyazaki, Nick Park, peak Pixar, and the other titles you mention (and much, much more), we didn’t know how good we had it. (And maybe we still don’t, given the utterly charming and evocative Oscar nominee Robot Dreams, from Spanish director Pablo Berger, slipped into theaters without much fanfare last week.) And as much as we think of animation, even more than live-action films, as a collaborative art form, maybe these bigger names, like Miyazaki, should be celebrated as singular contributors, creating little renaissances on their own.

I also love your idea of the spirit world changing for having had Chihiro in it, because I hadn’t given it any thought before. When Alice goes down the rabbit hole, the story becomes all about the weird and wonderful things that she (and we) discover in her adventures. It takes time for Chihiro to find her bearings in the world that Miyazaki creates here, so the beginning is about her survival, which relies on assistance from Haku, who keeps her protected until she can find her tenuous role in the coal-fired furnace of this immense and scary place. She never does get fully acclimated—and neither do we, since Miyazaki’s dream logic keeps inventing new rules on the fly—but she does make decisions that set her apart from everyone else. Maybe she is responsible for allowing No Face to enter the bathhouse and wreak havoc, but her integrity is what puts that crisis to an end.

That said, is Spirited Away a coming-of-age story? When Chihiro crosses that bridge to the other side, is that the metaphorical transition from childhood to adulthood? I’m not so sure. She’s definitely called upon to show reserves of courage and maturity that a 10-year-old is generally not expected to bring to the table, but I’d argue that her innocence is weaponized against the darker impulses of her adult foes, like Yubaba and Zeniba. But I think you’re right in Miyazaki offering Chihiro as a hopeful glimpse into a future generation: She will do better than her gluttonous parents perhaps—I say “perhaps” because she’ll be an adult with a credit card and an appetite some day—and the entire sequence with the Stink Spirit ties into Miyazaki’s longstanding concerns with the pollution of the planet, which here Chihiro is able to confront in her own determined way.

One last thing I will say about Spirited Away is that I’m scanning the notes I took from this viewing and they look like a crazy person wrote them. This is a compliment. While my notes will include observations and lines I will consider highlighting, they’re also just a reminder of the basic action of the film, such as “soot sprites give her shoes back,” which of course is what soot sprites do when they’re not hauling hunks of coal. Accepting the world Miyazaki has created for us is one of the chief pleasures of Spirited Away, and while the famed train sequence is as good a standalone piece of animation as I can recall, I think it benefits from the headspace the film puts you in before you get there. All the abstraction in this spirit world, combined with Chihiro’s struggles to find her footing there, eventually leads to acclimation, which then allows for sequence to work its magic, as we accept it on the terms Miyazaki has dictated. It’s a great feeling and one that makes the film endlessly rewatchable.

Next up, we return to Japan again, nearly half a century earlier, for a film I once considered my favorite of all time (it’s still close), Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. For those who haven’t seen it (and maybe for those who have), bring a handkerchief or two.

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

This is my favorite film. My parents also introduced Miyazaki to me at a young age and I became a bit obsessed with his work and Ghibli as a whole.

I’ve always seen Spirited Away as a coming of age film but it’s interesting to think about it as more of a revealing rather than a maturing. You certainly spend a lot of the movie in the moment with Chihiro and she doesn’t have a lot of time for self reflection, she’s gotta keep moving forward. Spirited Away is far from the kind of non-stop thrill ride that say, Fury Road is, but I think what makes the train scene stand out is that it’s a moment of calm, where the viewer and the character can reflect on everything that’s happened.

All I know is that at some point the girl complaining about not getting a goodbye bouquet in the beginning is gone and the one who can confidently stand up to witches and No Faces has taken her place. The dub even makes a point of highlighting how comparatively trivial her concerns at the beginning seem when at the end the dad asks her if she’s still worried about going to a new school. Was shocked when I finally watched the sub and realized that line was added to the English version. Maybe the coming of age angle wasn’t Miyazaki’s explicit intention then and the English language writers felt there needed to be some kind of button that could put the film into a more recognizable arc.

Thanks to it streaming on HBO, this is probably the animated film I've seen the most. Not only is it beautiful, but it's pretty funny as well. It also has way more vomiting than you would expect from the genre. I think Miyazaki must have owned a dog at some point, because the scene of Chihiro giving dragon Haku the emetic dumpling is a decent representation of trying to pill a dog.