In Review: 'Fly Me to the Moon,' 'Longlegs,' and 'Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger'

This week brings a rom-com set against the backdrop of the Apollo 11 mission, an unnerving horror procedural, and a documentary about a remarkable filmmaking team.

Fly Me to the Moon

Dir. Greg Berlanti

132 min.

It’s the winter of 1968 and, in the world of Fly Me to the Moon at least, NASA is in the grips of an identity crisis. Though it’s arrived at the last leg in the race to put a man on the moon, budget cuts, waning public enthusiasm, and the still-fresh memory of the Apollo 1 accident that took the lives of three astronauts threaten its continued viability. It makes sense, then, that Kelly Jones (Scarlett Johansson), an advertising ace experiencing lifelong identity issues of her own, would be the one to burnish its image. Kelly is plucked from Madison Ave. by Moe (Woody Harrelson), a shady Nixon White House operative—is there any other kind?—in part because a checkered past and a string of assumed identities makes her an easy target. (And, perhaps, because the similarly compromised Don Draper’s plate was already full.) She’s great at her job but quickly realizes, upon arriving in Florida, that this will be a more challenging assignment than repackaging Mustangs as family cars. That Cole Davis (Channing Tatum), NASA’s rigid flight director, has little interest in her project doesn’t help (however undeniable the spark of attraction is between them).

It’s apt, too, that Fly Me to the Moon also seems in the midst of an ongoing identity crisis. Its premise and look suggest a frothy ’60s comedy with Johannson and Tatum, respectively, dropped into the Doris Day and Rock Hudson slots.* Its tone, however, often belongs to a far weightier movie. Apollo 1 has turned Cole into a haunted man prone to fits of anger and melancholy. Kelly sparks on the idea of putting cameras on the moonbound Apollo 11 after realizing she has to compete for space on the nightly news with the Vietnam War. The result often plays like a comedy that’s too short on laughs or a drama that’s too lightweight to make much of an impact.

Yet while the Rose Gilroy-scripted, Greg Berlanti-directed film doesn’t really work, it somehow doesn’t really get in the way of it being thoroughly watchable. The dearth of anything resembling a comedy or romance in theaters might make it feel fresher than it would under other circumstances, but Tatum and (especially) Johansson’s willingness to commit to whatever kind of movie Fly Me to the Moon wants to be from scene to scene goes a long way. Even they struggle, however, to sell the film’s final transformation into wackadoodle farce after Kelly reluctantly commits to shooting a fake moon landing as a kind of backup should the real thing not work out as planned. Not only does this not make much sense—logically or logistically—it lies flat on the screen apart from Jim Rash’s contributions as the project’s demanding, and perfectly named, director, Lance Vespertine. The film’s high-concept selling point emerges as the weakest element, turning the final stretch of an already long movie into a frenetic drag. And yet, in spite of it all, Fly Me to the Moon remains both easy to watch and easy to like—a little, if never a lot. In the absence of greatness, sometimes you have to settle for good enough. —Keith Phipps

* This seems like a good place to provide a reminder that Down with Love a) exists and b) is a lot of fun.

Longlegs

Dir. Osgood Perkins

101 min.

Few first big assignments go as memorably, or as poorly, as that of FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe). When she and her partner Horatio (Dakota Daulby) receive the task of going door-to-door in a dull suburb in search of a serial killer, it seems like the definition of grunt work. Until, that is, Lee suspects— no, knows — the killer can be found behind the doors of one house. Horatio objects to calling in reinforcements on a hunch, but what follows proves Lee right—in almost the worst way possible. It also gets her noticed by her superiors, who keep an eye out for agents with psychic gifts, and earns her a new assignment: the hunt for an elusive figure tied to, but seemingly not responsible for, a string of horrific murder-suicides that have taken out whole families for years. They know him only because he leaves notes written in a bizarre code except for the signature: “Longlegs.”

Written and directed by Osgood Perkins (The Blackcoat’s Daughter), Longlegs only sounds like a film that can be boiled down to its influences. Set in the 1990s, it immediately suggests The Silence of the Lambs with a touch of The X-Files. The cryptic messages and twisted psychology bring Zodiac to mind. The possibility of a supernatural connection and its depiction of desolate, Clinton-era American landscapes and creeping nihilism layer in a dusting of True Detective’s first season. But for every familiar element, the film offers its own, original spin. Monroe’s performance as a terse, brilliant agent trying to navigate a male-dominated world, for instance, only superficially resembles an archetype defined by Dana Scully and Clarice Starling. The way she combines a resolute stare and all-business demeanor with a tremulous, almost childlike voice and sense of muted-but-mounting terror makes the character wholly her own.

That’s true of Longlegs at almost every level, thanks to Perkins’ unnerving, disciplined style. If the film’s world feels familiar, Perkins’ approach does not. In place of jolts, he favors long takes and an occasionally unbearable sense of dread. It’s the sort of film sure to trigger many viewers’ flight instincts. Then there’s Longlegs himself, effectively made absent or kept obscured in the film’s early scenes and played by an almost-unrecognizable Nicolas Cage when he does appear. Cage has depicted villains before and more than a few unhinged types (it’s kind of a trademark) but never a character as consistently, upsettingly scary as the one he plays here, a fringe dweller whose enthusiasm for T. Rex songs is outmatched only by a (possibly reciprocated) love of Satan.

The film’s story, too, takes it to some unexpected places, and brings in twists and elements that never quite cohere. As a narrative, Longlegs’ logic doesn’t really survive the ride home from the theater—if, that is, you can put yourself together long enough to scrutinize its plot. As an abyss-black mood piece filled with disturbing moments, memorable characters, and borderline apocalyptic atmosphere, Longlegs is an unmitigated success. Nightmares don’t always stand up to scrutiny, either, but that doesn’t make them any less haunting. —Keith Phipps

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger

Dir. David Hinton

131 min.

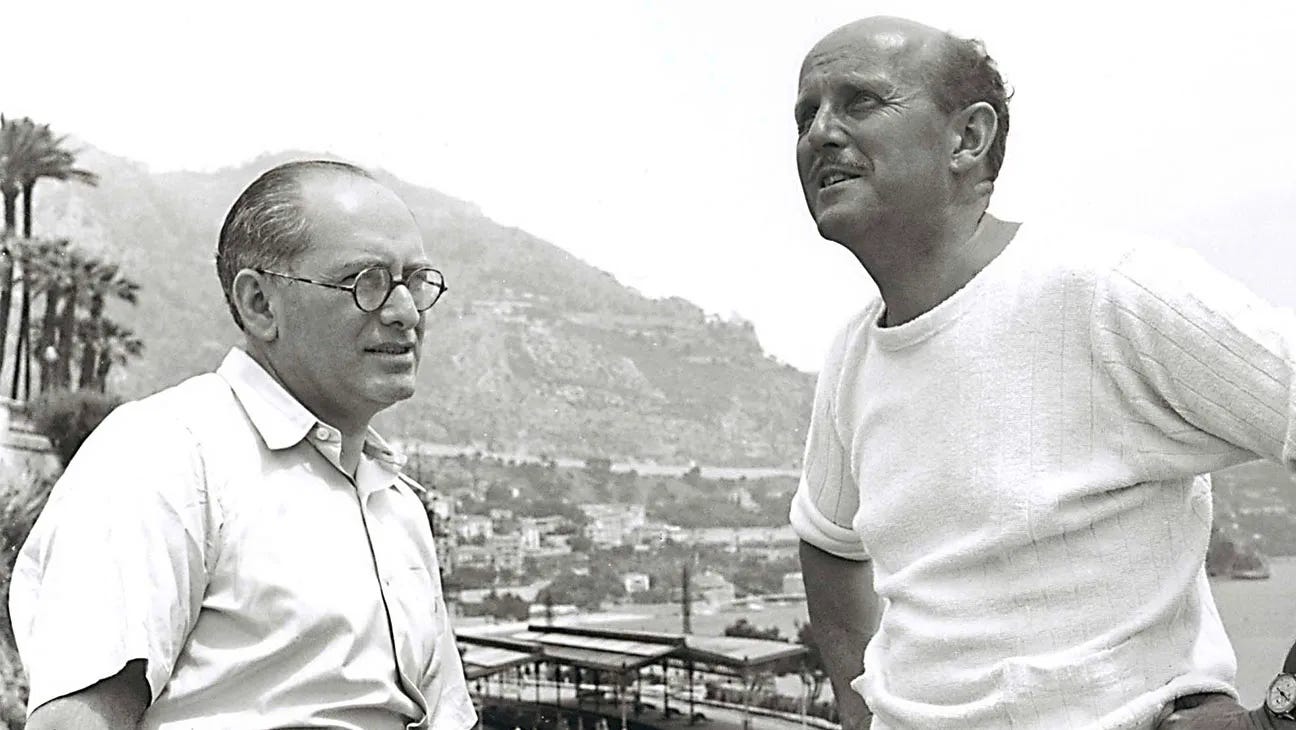

Falling in love with movies can feel like opening a series of doors: You respond to one filmmaker and you want to see everything they’ve done. Then you want to know who influenced them and more doors open. With Martin Scorsese, you’re unlocking a palace of endless corridors and ceaseless wonders, because the question of who influenced him has more answers than one person could reasonably consume in a lifetime. Yet there are some specific obsessions of Scorsese’s that have been outlined in documentaries before, specifically two in the mid-to-late 1990s: A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through a American Movies, a three-part, 225-minute that organizes directors as storytellers, smugglers, illusionists, and iconoclasts; and My Voyage to Italy, a 246-minute accounting of Italian cinema, bookended by Robert Rossellini’s neorealist classic Rome, Open City and Michelangelo Antonioni’s modernist L’Eclisse. They’re like the best film studies classes you’ve ever audited.

Though it took Scorsese longer than expected to get around to a disquisition on Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the British filmmaking team that has informed his relationship with movies since childhood, it seems inevitable that he would finally get around to it. And while Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger is not directed by Scorsese—David Hinton, a doc profiler of many British artists, gets that honor—it’s built around him in the same way. He is the sole narrator and he has the audacity (and cred) to talk about other directors through the prism of his own work without minimizing their importance or making it all about him. There’s a warmth and approachability to Scorsese’s narration, on top of the implicit acknowledgement that artists like him are inspired by other filmmakers’ work and build upon it.

It might seem strange to imagine a time when Powell and Pressburger, also known as “The Archers,” were not obviously canonical favorites, but when Scorsese and other New Hollywood types like Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma were coming into prominence in the early ‘70s, their reputation had hit the skids. Scorsese found Powell in a kind of cinematic exile in Britain, living modestly in the countryside while a younger generation of directors like Tony Richardson and Lindsay Anderson were taking their cues from the French New Wave. In Scorsese’s telling, Powell was surprised and flattered by his enthusiasm and by the way The Archers’ dynamic, sensually arousing style had seeded the American scene. The two became friends and Powell would marry Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese’s longtime editor.

Though Made in England sets up The Archers’ films through a flurry of arresting images and Scorsese childhood mythos—he recalls his rapture seeing The Thief of Bagdad repeatedly on TV (in black-and-white!)—it ultimately settles into a straightforward, chronological accounting of their collaboration. More time is devoted to certain films than others, like Scorsese favorites The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and The Red Shoes, as well as Powell’s solo film from 1960, Peeping Tom, which studied the relationship between the camera and sexual violence with a lurid punch that scandalized British critics.

Scorsese gets enough distance from the material to recognize the shortcomings of The Archers’ lesser work, when they had trouble with meddling Hollywood producers and a fraying creative partnership. But there’s enough real estate given to each film to make Made in England a substantive critical companion for fans and an enticement for newcomers. And when Scorsese gets cooking on a less-known but still thrilling production, like Gone to Earth… well, that’s another door opening. — Scott Tobias

Keith, I'm curious about your take on the wisdom and/or morality of a big-budget movie that more or less endorses a persistent conspiracy theory in our current age of such rampant, dangerous misinformation. I have to say, whatever the charms of FLY ME TO THE MOON, I've been put off by the premise ever since first seeing the trailer. Like, violently put off.

I saw Longlegs last night and enjoyed itbquite a bit. I agree with Keith on both counts that it's a creepy, atmospheric film with a plot that doesn't quite hold up to scrutiny. The film definitely has some intentional humor, but my theater had a smattering of awkward laughter during scenes that didn't seem to warrant it. Nic Cage is so gonzo throughout (like Heath Ledger's Joker crossed with Tiny Tim) that it's hard not to admire the audacity of his performance and the film as a whole.