Caught Looking: The Unsavory Allure of ‘Peeping Tom’

Lost, rediscovered, and newly restored, Michael Powell’s lurid tale of murder and filmmaking has lost none of its power to disturb.

“I’m told by a friend that you have some views for sale,” a conservatively dressed customer (Miles Malleson) quietly asks Mr. Peters (Bartlett Mullins), the proprietor of a corner news shop early in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. After a short interaction in which they discuss what, precisely, the customer is looking for and the price of his selection, Peters brings what he already knows his customer wants from behind the counter, cuts him a deal, and sends him on his way, his purchase wrapped in a package labeled “Educational Books.” It’s a breather, a comic moment with none of the violence and dread of the film’s ostentatious opening—the murder of a sex worker as seen through the lens of a camera—but it also speaks directly to the film’s central theme: What’s the price of looking? And what’s the cost of being seen?

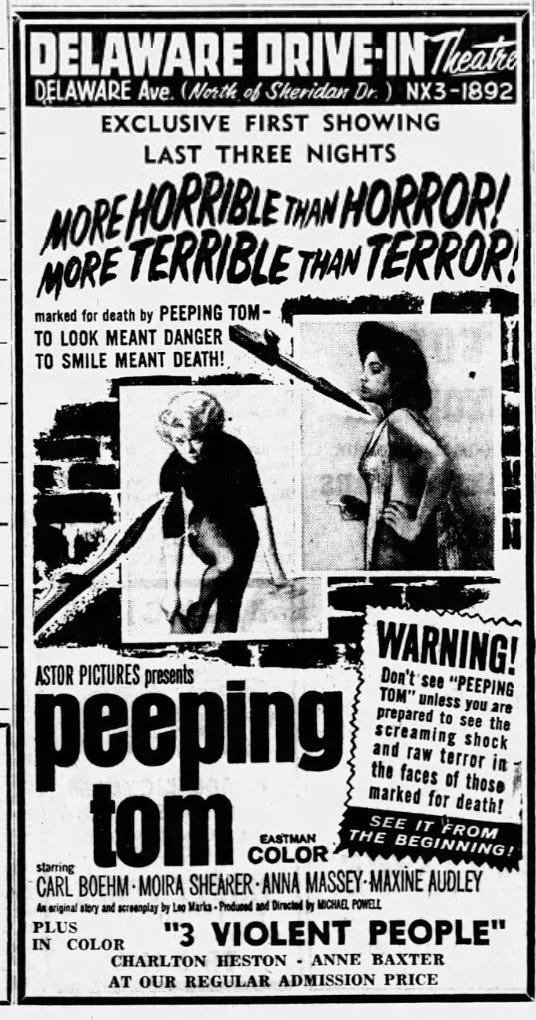

These aren’t questions many in 1960 felt comfortable considering, or at least not in the form posited by Peeping Tom, which has become almost as famous as the film that killed, or at least severely injured, the director’s filmmaking career. As the story goes, Peeping Tom opened to such hostile reviews in Britain, it essentially disappeared. In interviews, Powell recalled it being pulled from theaters before completing even a week in release. The full story is a bit more complicated. Peeping Tom picked up a few sympathetic reviews alongside the shocked pans and even inspired protests when it was banned in Warwickshire the following year alongside Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and a handful of other titles. It made its way around the United States, where it was marketed as an exploitation film, and much of the rest of the English-speaking world in the years that followed. But it was a commercial failure by any definition, and became a film more read about than seen until its rediscovery decades later, thanks in part to the vocal championing of fans like Martin Scorsese.

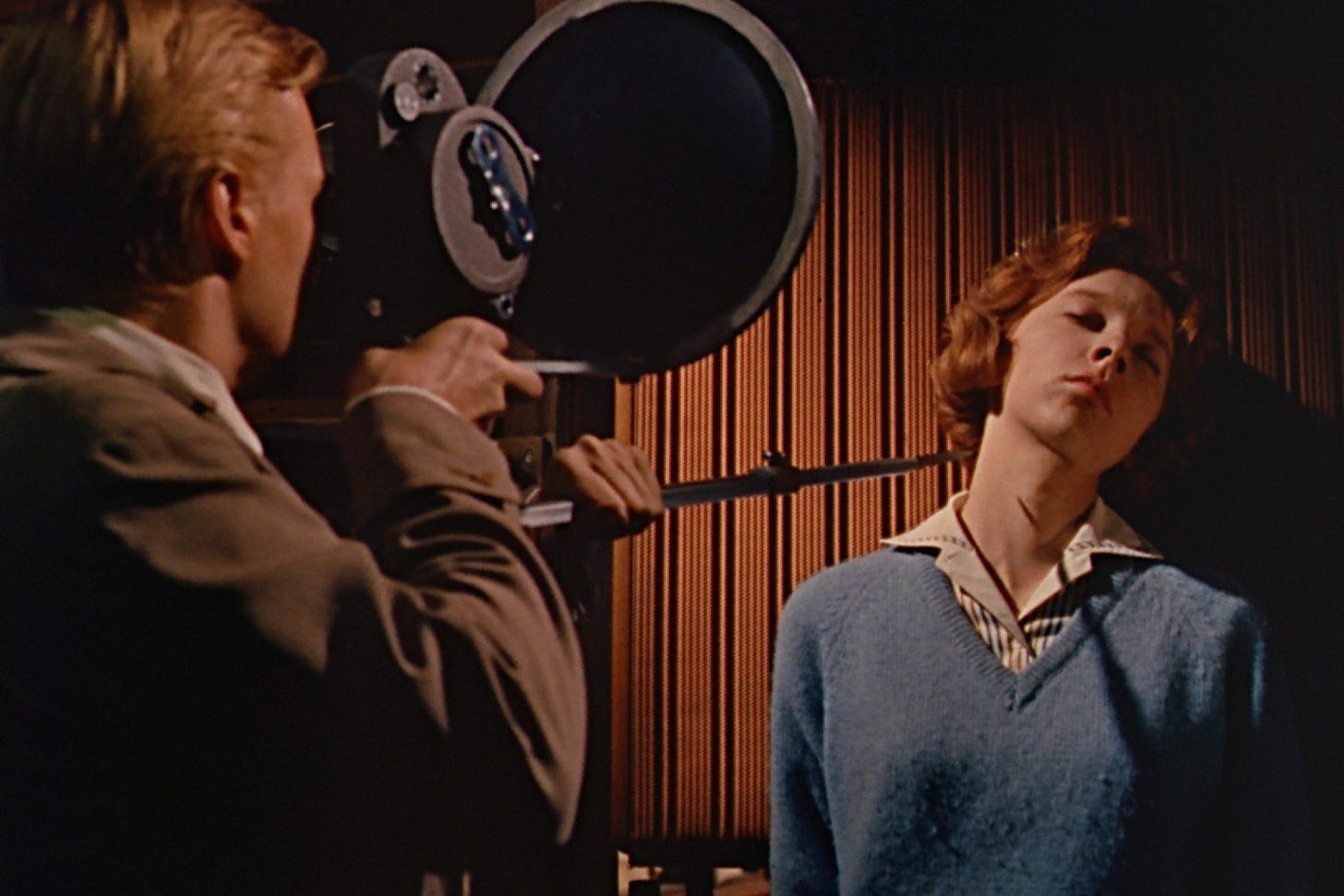

That reclamation has continued with the film’s recent 4K restoration which, as seen on Criterion’s newUHD and Blu-ray edition, looks remarkable, capturing the full lurid beauty of cinematographer Otto Heller’s work. Peeping Tom is neglected no more, yet there was something kind of apt about its semi-underground status in the long stretches between its home video releases in various formats. It remains a deeply unsettling film about a voyeuristic psychopath that makes co-conspirators of all who watch it. It plays like a movie that should be kept behind the counter and asked for in hushed tones. The typically beautiful cover of the Criterion set is the cinephile equivalent of dropping it in an “Educational Books” sack.

Killing Powell’s career was no small feat and at least part of the responsibility belongs to Peeping Tom screenwriter Leo Marks. Powell remained a director in high esteem in the 1950s, though his most acclaimed films, made in collaboration with Emeric Pressburger, belonged to earlier decades. Their partnership wound down amicably in the mid-1950s, as each pursued his own projects. For Powell, that meant finding new collaborators. Enter Marks. The heir apparent to Marks & Co., the London bookstore that plays a central role in Helene Hanff’s 84, Charing Cross Road and its adaptations, Marks served as a cryptographer in World War II and had a reputation for eccentricity and wit (qualities very much in evidence in Chris Rodney’s 1997 documentary A Very British Psycho, which is included in the Criterion set and streaming on the Criterion Channel). In the story of an aspiring filmmaker—or at least that’s his cover story—with a murderous streak, the writer and director found material that suited them both.

Marks (sort of) lends his name to Peeping Tom protagonist Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), a shy young man who lives in the top-floor apartment of his family home, which has been converted into a boarding house (though even his tenants don’t know that he’s their landlord). Mark spends his days working on a focus puller for feature film productions and his spare time taking nude photos in a studio above the shop where Mr. Peters sells the photos to his customers. (He’s a vertical integration pioneer.) And though we know he’s a murderer, Mark still seems like a misunderstood misfit, particularly after he catches the attention of Helen (Anna Massey), a kind first-floor tenant who’s drawn to him despite his reclusiveness. It’s one of the film’s neatest, and nastiest, tricks that Mark never becomes fully monstrous to our eyes, no matter how awful his deeds. It’s the dark side of Roger Ebert’s “empathy machine.”

Powell bakes that discomfort into the design of the film. We watch Mark as Mark watches and see what he sees as he seeks out victims and films their deaths, murdering them with the pointed end of his camera’s tripod. (Freud’s shadow hangs over the film.) Alone at night, he watches what he’s filmed. Mark doesn’t lack self-awareness, describing himself as suffering from scopophilia in conversation when talking with a psychiatrist brought to the set of the film after one of Mark’s murders. In fact, he was shaped to become one by his late father, also a psychiatrist, who treated his son’s childhood as a long experiment. And it’s one he captured on film, letting the camera roll as he placed a lizard on his sleeping son’s chest and reacted to the sight of his mother’s corpse. This echoes (fervently denied) rumors that behaviorist B.F. Skinner would use his own children as guinea pigs. (For what it’s worth, Powell himself plays the father. His son plays Mark as a boy and his wife served as a stand-in for the corpse.)

Decades later, it’s easy to conclude that Peeping Tom was a film ahead of its time in its violence. Yet its death scenes were no gorier than what Hammer’s horror films offered. They were, however, grislier, more prolonged, and, perhaps most damningly, more intimate than audiences were used to seeing. Released the same year, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho would enjoy tremendous success with a story built around a similarly sympathetic voyeuristic serial killer unable to escape the shadow of an oppressive parent. But Hitchcock rarely leaves us alone with Norman Bates and the director’s remarkable style provides another buffer. Hitchcock never allows us to forget that we’re watching a show staged by him for our entertainment. Psycho only flirts with implicating the audience’s desire to watch the salacious, unsavory, violent with the actions of the killer on screen.

Peeping Tom offers no such comforts. Powell’s style is different. Though a departure in many ways from beloved films like A Matter of Life and Death and The Red Shoes, Peeping Tom keeps their deep investment in its character’s humanity, however twisted that humanity has become. By the very act of choosing to sit in the dark and watch a film about a killer we’ve slipped halfway into Mark’s shoes already. Peeping Tom is the shoehorn that completes the act.

Let’s circle back to those negative reviews. It’s easy to lump Peeping Tom’s critics together and file them all in a folder labeled “Didn’t Get It,” but maybe there’s more to it. In The Birmingham Post, Keith Brace dubbed the film the “‘shocker’ of the year,” praised the filmmaking then concluded it was a film that simply should not exist. “[T]he subject, psychopathology, is, I am sure, not film material,” Brace writes. “Acceptable in literature, where the mind can stand back, reflect, and link it to broader contexts, it is reduced by the swift, unreflective techniques of the cinema to sensationalism.” Remove the value judgments around the words “reduced” and “sensationalism” and it reads like a rave. Brace concludes the review by stating that, “[t]he film is ultimately not free from suspicion as a symptom of the aberration it describes: the morbid desire to gaze on human distress. Brilliant. Perverse. Unforgettable. Unnecessary.” Only the “unnecessary” that feels wrong.

There's a new documentary about Powell and Pressburger out called "Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger" that talks about this film (and many others). Saw it at the Hot Docs festival in Toronto, and it was quite good.

I've always thought Powell used color better than any other filmmaker, and this could serve as Exhibit A--every single frame here is so queasily lurid, it could be used to define the word.