#67 (tie): ‘Andrei Rublev’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Andrei Tarkovsky's second feature offers an episodic, largely invented look at the life of a 15th century icon creator amidst an unsparing depiction of the oft brutal world in which he lived.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

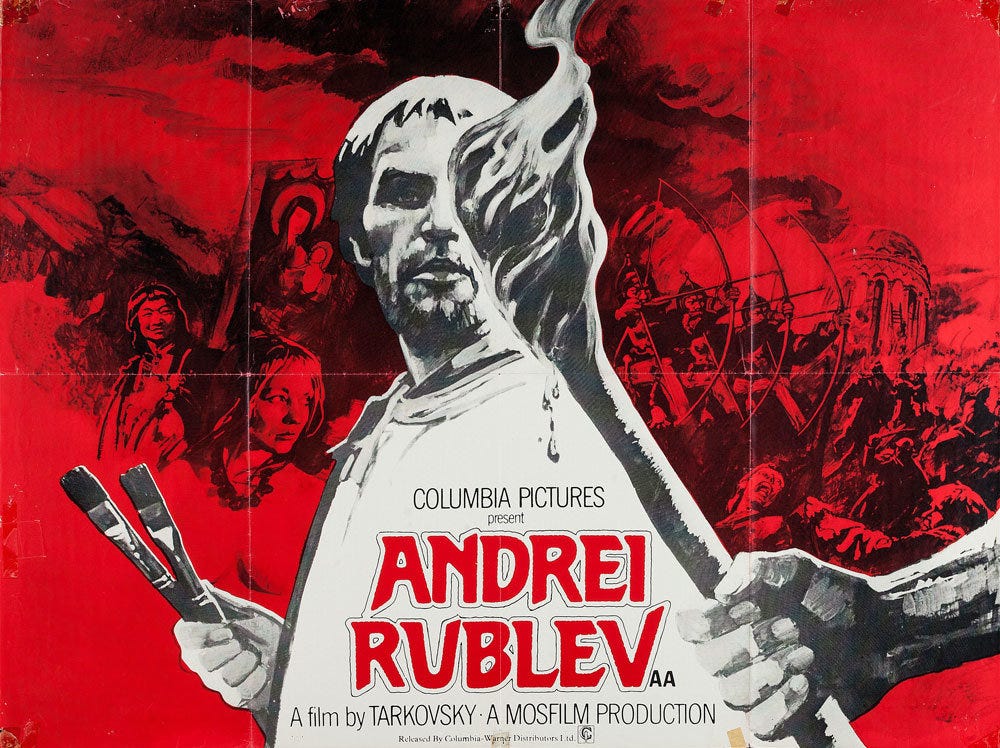

Andrei Rublev (1966)

Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky

Ranking: #67 (tie)

Previous rankings: #27 (2012),#27 (2002), #18 (1992), #12 (1982)

Premise: The place: Russia. The time: the first decades of the 15th century. It’s a muddy, brutal land where duplicitous princes and boyars rule over serfs with the help of Tatar warlords. It’s not, in other words, the sort of place where art naturally thrives, to say nothing of faith, compassion, or charity. For Andrei Rublev (Anatoly Solonitsyn), a monk and painter of icons, the act of creation is bound to those virtues, despite an environment seemingly designed to snuff them out. Andrei Tarkovsky’s story of the revered Russian artist — mostly the invention of the director and his co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky, as little is known of Rublev’s life — takes the form of eight episodes sandwiched by a prologue and epilogue. In the first episode, Rublev sets out for Moscow with two fellow artists. In the final episode, he finds the inspiration to resume his work as an artist after previously taking a vow of silence. In between, Andrei experiences everything from a festival of pagan hedonism to the staging of a Passion Play to a brutal raid, experiences that shape his artistic developmentand inform his view of the world.

Keith: A thought occurred to me while watching the epilogue of Andrei Rublev: The film runs over three hours (in Tarkovsky’s preferred cut) and includes nine sections, but it’s ultimately a long prologue. The film’s only color sequence, the epilogue offers some close looks at Rublev’s art on the heels of the final narrative scene, in which Rublev breaks his silence and rededicates himself to art, inspired by the efforts of Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev), a young bellmaker who’s collapsed and begun weeping after successfully orchestrating the creation of his first bell. Though we see scenes of Rublev as a professional artist, the work featured in the epilogue all lies ahead of him as the narrative portion of the end closes. These, Tarkovsky seems to suggest, are the masterpieces created after hours of depicting the unlikeliness that an artist of extraordinary talent could accomplish anything in medieval Russia.

Andrei Rublev has been called one of the most historically accurate depictions of medieval life, though I couldn’t help think of the film one of my college professors held up as her pick for the most accurate medieval movie: Monty Python and the Holy Grail (ignoring the coconuts that fill in for horses hooves, of course). Specifically, I kept remembering the moment when one peasant points King Arthur out to another, secure in the knowledge that he’s spotted the king because, “He hasn’t got shit all over him.” I don’t know that Tarkovsky specifically set out to counterprogram movies that treated the Middle Ages romantically, but, beyond being historically accurate, Tarkovsky’s depiction of 15th century Russians as mostly being wet, undernourished, and, yes, covered in shit, has that effect anyway.

This was my first time watching Andrei Rublev and I’ll confess here to using a couple of bathroom breaks to consult the Wikipedia page to make sure I had all the characters and actions straight. (I was swimming a bit in the “Last Judgment” sequence, particularly the scene in which some of Andrei’s co-workers are blinded by the thugs of a pissed off duke.) Tarkovsky isn’t all that concerned with easing viewers into the world of the film, particularly given that he starts Andre Rublev with a scene of a hot-air balloon flight that’s connected to the rest of the film only symbolically. That said, it’s an amazing scene, the first of many moments in which Tarkovsky’s skill as a technician, composer of images, and choreographer of seeming chaos.

I’m not entirely sure where to start with this film. Maybe it’s best to start with the sequence where it gelled for me that Tarkovsky wanted to tell the story of both Rublev’s artistic development and the evolution of his soul. In “The Holiday,” Rublev leaves the others in his party behind and stumbles on a group of pagans celebrating the summer solstice. They’re nude, exuberant, and, when they discover their Christian interloper, quite hostile, binding him and promising to kill him in the morning. But one pagan, a woman named Marfa (Nelly Snegina), first mocks then takes pity on him, eventually letting him go. But before she does, an erotic charge passes between them that Rublev does not act on.

It’s a pivotal moment for the monk, who could act on his impulses and abandon his principles for a more pleasurable life, but doesn’t. Then, the following day, he watches as soldiers round up the pagans. Marfa, after again stripping nude, attempts to escape by swimming away, passing a boat containing Andrei and his companions in the process. Does she get away? We never learn. The moment passes and is gone, but for Rublev it’s another incident that shapes his identity, just as his refusal to depict The Last Judgment out of a desire not to frighten people into belief will in the next chapter and the destruction of his art and decision to kill will in the chapter after that. Andrei Rublev is both a sweeping depiction of a tumultuous period in Russian history (if there’s any other kind) and a bildungsroman focusing on one man’s spiritual and artistic development. The film tells an extremely big story and an extremely small one at once, but makes them seem inextricable from one another.

Scott, this was not your first trip through Andrei Rublev’s Russia, how was your return visit to the film? And while I’ve talked about this as a film about the 15th century, it’s not unconnected to Tarkovsky’s time, is it?

Scott: I’ve been fortunate enough to see a few Tarkovsky films projected and Andrei Rublev was one of them, though I hadn’t seen it since it screened at the campus theater in the early ‘90s. But I never forgot the hot air balloon sequence that opens the film and I remembered the creation of the bell so vividly you’d think I’d just seen it last week. It’s hard to believe that Andrei Rublev was only Tarkovsky’s second feature—or, at least, it would be if you hadn’t seen his first, 1962’s Ivan’s Childhood (also titled My Name is Ivan), which remains his most accessible work and an electrifying piece of filmmaking, with an active camera and a more fleet narrative than you’d expect from man whose later work bent toward the deliberate and philosophical. In a way, that makes Andrei Rublev a transitional work between Ivan’s Childhood and his next film, 1972’s Solaris, which is made more in the mode people might expect from Tarkovsky.

In any case, what a picture! Andrei Rublev is the first of three Tarkovsky films we’ll encounter on the Sight and Sound list—Stalker and Mirror are ahead of it—which makes him second only to Alfred Hitchcock, who has four in the Top 100. It’s been interesting to see Rublev tumble a little in the 21st century in critical appreciation relative to, say, Stalker, which has gotten more attention as a foundational work in screen science fiction (and nuclear-era politics). But it’s in that sweet spot for me as being arresting as pure cinema and being such a rich study of a righteous man who struggles to reconcile his divine gifts as an artist with the injustice and suffering that he sees all around him.

Let’s look at where this journey starts, with a chapter called “The Jester,” where Rublev, along with two other monks, Daniil (Nikolai Grinko) and Kirill (Ivan Lapikov), duck into a barn to seek shelter from a driving rainstorm. (Even the weather seemed inspired by the cruelty of the era.) Once there, they’re among a large group of people guffawing at the antics of a jester, or skomorokh, who is drunkenly savaging the political and religious powers-that-be. The monks take offense at the routine, including Kirill, who steps outside, and at the end of the chapter, soldiers arrive on horseback to arrest the skomorokh, knocking him unconscious and dragging him away to some unenviable fate. When the jester reappears later in the film, still upset about the turn his life took that day, we’ll learn from a remorseful Kirill that he was responsible for siccing the authorities on the man. But for the much quieter Andrei, it’s the first of many lessons he learns about the real-world injustices that are common outside the monastery. He never succumbs to the low behavior of the jester or the pagan that you reference above, but he’s aligned with their plight from that moment forward.

The chapter-based approach of Andrei Rublev allows for such a wonderful variety of episodes in Rublev’s odyssey, all leading to the emotional point where this monk, disillusioned into silence and inactivity, is inspired to speak and paint icons again. The type of art he wants to create—hopeful, generous, inspirational, connected to the plight of ordinary people—keeps bumping up against the corruption and violence that grips medieval Russia, from cold-blooded aristocrats to lusty Tatar invaders to the countless Men On Horses who terrorize the populace. Rublev holds himself to an extremely high standard, refusing as you say to follow through on his lust a pagan tempress and later taking a vow of silence for killing a Russian soldier who plainly intends to rape Durochka (Irma Raush), the “holy fool” who comes into his orbit during the “Last Judgment” job. The gulf between his values and grotesque sins around him are hard for him to reconcile and it takes a kind of artistic miracle to set his mind straight.

I’ll save my thoughts on the film’s biggest chapters—the pillaging of Vladimir and “The Bell”—for later, because they’re worth unpacking at greater length, but I do appreciate the way Tarkovsky sequences the film to where these setpieces come toward the end, like a snowball effect in Rublev’s conscience. As for the contemporary political context, our old friend and colleague Matthew Dessem, in his Criterion Contraption entry on the film, feels it’s “impossible to watch this movie without thinking of Stalin,” who ruled the country with cruel severity for the first 20 years of Tarkovsky’s life. Those are formative years for Tarkovsky as a young person with an artistic sensibility and he surely put himself in the mind of an icon painter coming into his own in an environment where humane art must have seemed impossible.

What else do you make of Tarkovsky’s take on Rublev, which he took a pretty free hand in imagining? And were you as blown away as I was by the sheer spectacle of this film? The scale of the raid on Vladimir and the presentation of the bell, in particular, took my breath away.

Keith: I wish I could have seen this screened. (Maybe someday I’ll get the chance.) But even at home, the widescreen black-and-white cinematography and the skill with which Tarkovsky stages grand scale action without losing the individuality of the characters on screen is pretty stunning. The raid chapter is particularly strong on this last point. It brought Seven Samurai to mind for me. But one of the most striking moments is something I’d never seen before: the way Tarkovsky cuts from the action outside to the Vladimir residents huddled inside the church, who’d been off screen to that point in the chapter. We’ve been watching the raiders for so long that the switch in POV is kind of shocking, an effect enhanced by the contrast between the settings. Outside it’s noise, action, high spirits, and sunshine. Inside it’s quiet, stillness, fear, and shadows.

As for Tarkovsky’s take on Rublev, it took a while for me to get a handle on the character, but I think that’s by design. The film’s about Rublev’s emergence as an artist and, as the film opens, he’s a bit unformed. It’s the moment when he explains why he doesn’t want to paint the Last Judgment that he fully emerged as a character I understood. He’s not just a skilled artist, he has a vision of the world he wants to convey through his art. Then, in retrospect, you can see the pieces coming together: the affinity with outcasts that begins with the encounter with the jester, the argument with Theophanes the Greek in which his mentor reveals a cynicism Rublev cannot understand an artist possessing, his temptation by the pagan, and so on.

As you mentioned, Tarkovsky essentially invented Rublev’s biography for the film. Given how much art from the pre-modern era is anonymous or of murky origin, it’s lucky we have a name at all. (And even so, there’s really only one work, the Trinity seen in the epilogue, that can be definitively attributed to Rublev.) In some ways, Andre Rublev is an act of extrapolation, as if Tarkovsky looked at the art and attempted to imagine what kind of artist would produce it. I don’t know enough about Rublev’s art to suggest he got it right or wrong, but Rublev undoubtedly emerges as a complex, soulful character.

He’s not the only one, however. In fact, some chapters of the film sideline him for long stretches, particularly “The Bell,” which largely belongs to Boriska, the young bell-maker who fakes his way into receiving an important commission by falsely claiming he alone possesses the secrets of his late father, a master bellmaker. Played by Nikolai Burlyayev, the star of Ivan’s Childhood, Boriska undergoes his own emergence as an artist, in fast forward. How do you see his story playing into Rublev’s?

And, to get meta for a moment, Burlyayev has gone onto become a repressive, Putin-supporting member of the Russian State Duma who’s proposed chastity lessons to steer girls toward adhering to Orthodox beliefs and called for the prosecution of artists expressing dissenting views on Ukraine. In some ways that’s irrelevant to this discussion, but in other ways it’s not. Though Tarkovsky received state support for Andrei Rublev, he had trouble with the censors. That led to multiple cuts and difficulty in getting any cut seen at all. Andrei Rublev was allowed to screen out of competition at Cannes, but only in a middle-of-the-night screening. Beyond the violence Tarkovsky, who was Orthodox, made a film depicting the centrality of faith to Russian identity, which didn’t exactly square with the party line. Obviously that had to be frustrating and Burlyayev seems like a total dick, but it also seems kind of apt: a film about the difficulty of making art in 15th century Russia became a 20th century work of Russian art that had trouble getting released. And itfeatured in its cast an actor who would go on to be part of a repressive regime in the 21st century.

Scott, in addition to your thoughts on Boriska I’m interested in your take on Rublev’s character. And, hey, let’s talk about those big sequences we were saving for later. This is probably true of most chapters, but “The Raid” could be a film onto itself, couldn’t it?

Scott: My god, all that background about Burlyayev is so depressing to hear! There are poisonous snakes at the bottom of these internet rabbit holes sometimes. But credit where it’s due: He’s extraordinarily compelling in both of Tarkovsky’s films and so crucial to Andrei Rublev achieving the emotional impact it builds toward in the chapters leading up to “The Bell.” When we first come across Boriska, he’s in a desperate state, having lost his father, the real expert bell-maker, to the plague, along with his mother and sister. It’s a high-stakes bluff for him to claim that he learned his father’s secrets before he died—we learn later, in a tearful confession to Rublev, that the old bastard did not mentor him at all—and even when the bell has been successfully cast, Boriska and his men will be killed if it doesn’t ring. (The Grand Duke could not suffer such embarrassment in front of a foreign visitor.)

So what are we to make of what transpires? Is Boriska a true artist, touched by the divine hand? Is this a miracle, signaling a God who may be more merciful than this time and place had led us to expect? Certainly he’s as demanding as you’d expect an artist to be: I can’t be alone in making the connection between Boriska marshaling dozens of men to pull this enormous bell up through a crude pulley system and Werner Herzog, decades later, enlisting indigenous people, to drag a steamboat up a hill for Fitzcarraldo. There’s madness in this kind of ambition and an uncompromising vision, too, particularly in the type of clay that he insists they use for the mold. What makes him so certain? And how can a total novice make such brutal demands of his workers? He has a man whipped for defying him! He even gets irked that the miserly Grand Duke isn’t giving him enough silver to melt down for the task.

And yet, even though the bell is eventually raised and he has his moment of triumph—this after a long, suspenseful stretch where the clapper swings back and forth, not quite striking—Rublev is initially drawn by the young man’s self-doubt. Maybe he doesn’t realize that Boriska doesn’t really know what he’s doing, but he can recognize the torment of an artist who struggles to make art. Rublev comforts Boriska again after the bell rings and he finally brings himself to speak again: “You cast bells,” he says. “I paint icons. What a feast day for the people.” That last line calls back to “The Last Judgment,” when Rublev realizes what he wants to paint isn’t what he’s been commissioned to paint. He wants his art to connect to common folk, not aristocrats, and the bell belongs to everyone, despite starting as a vanity project for the Grand Duke. It can be heard across the land, after all, and will still ring long after the Grand Duke is dead.

There are so many beautiful shots in Andrei Rublev. I’m particularly fond of the misty forest in “The Feast,” which gives cover to the wild, liberated pagans who bewitch Rublev before the soldiers come along. But Tarkovsky saves his most majestic work for the pillaging of Vladimir and the creation of “The Bell,” both of which include several long shots that take in full villages or landscapes with tons of extras scurrying around in the frame. When the Grand Duke’s brother agrees to join the Tatars in their vicious raid on Vladimir, you get the sense that he doesn’t realize the scope of what he’s abetting until later, when Tarkovsky shows him looking down on the destruction and savagery and seeming remorseful about his role in it. (We learn later that his brother had him killed for taking part.) Throughout the sequence, the Tatars and their Russian cohorts look all-too-pleased to be terrorizing people, and Tarkovsky renders it with such force that we can understand why Rublev vows silence after taking part, even if his violence was in a woman’s defense. The world seems beyond salvation to him and certainly not suited to the types of paintings he wants to do.

And how about that epilogue, Keith? It’s not exactly The Wizard of Oz to go from nearly three hours of black-and-white to the color of Rublev’s actual work (or possible work), but it does serve an interesting purpose. Here we have a biopic about a famous medieval icon painter that never once shows him at work. I’ve been trying to think of other films about famous people not to feature some piece of what they’re known for, but the only title that comes to mind is Young Mr. Lincoln, which still gives us a vivid child-is-the-father-of-the-man portrait that leads into what we already know about his history as President. Here, Tarkovsky suggests that the era itself might have been so wicked and unjust that Rublev might never have realized his potential. As it stands, we see Rublev’s work in bits and pieces, rather than a more conventional slideshow-style compilation. I’m not sure how I feel about that or about the final shot of horses in the rain, but there’s a tactility to both that feels right. That Tarkovsky ends with “Christ the Redeemer” is a statement in itself, I think.

Keith: It’s not a movie afraid of boldness, that’s for sure. And, in a different way, the same could be said of our next film, the second of five films tied in the #67 spot: Agnes Varda’s The Gleaners and I. And, in case you missed it and want some Varda talk before we get to it, check out our interview with Varda biographer Carrie Rickey.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

I was lucky to see this projected a year before COVID. The Bell had me absolutely spellbound and the color epilogue elicited an audible gasp from me. I didn't know much of anything about the film going into it which I think made the ending quite potent for me.

It’s been almost exactly one decade since I caught a repertory screening of this. As I wrote at the time, it’s the kind of film that humbles and ennobles the viewer in equal measure.