Interview: Carrie Rickey on 'A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda'

The critic and scholar discusses her new biography of the pioneering filmmaker and what she discovered while writing it.

Agnès Varda was born in Brussels in 1928 and died in Paris nearly 91 years later. In the years between, her career took her around the world, first as a photographer, then as a filmmaker and later an installation artist. It was, in many ways, an unlikely and uphill journey. When Varda made her first feature, the 1955 film La Pointe Court, she had not only not studied filmmaking, she'd only seen a few films. Though it predated the work of François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and other French New Wave figures—the “Cahiers boys,” in Varda’s term—she at first had to settle for being called “the grandmother of the New Wave,” rather than a member in her own right.

In some ways, however, its apt that any attempt to label Varda would be inaccurate. Varda was tough to define or pin down. Financing didn’t always come easy, but Varda found ways to keep working anyway, alternating narrative features with documentaries, shorts, television projects, and advertisements while working from a home base on Rue Daguerre in Paris’s Montparnasse neighborhood. Her output in the ’60, ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s included Cléo from 5 to 7 (probably still her best-known film); the scathing portrait of a marriage in Le Bonheur; One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, in which the French women’s movement and struggle for reproductive rights serves as the backdrop for a story of two women’s friendship; and Vagabond, starring Sandrine Bonnaire as a doomed, unknowable wanderer.

When film changed, so did Varda. With her 2000 film The Gleaners and I, Varda embraced digital technology and began making the documentaries and essay films that would define the last phase of her filmmaking career. Putting herself—and her colorful wardrobe and multi-colored hair— front and center, Varda helped win over a new generation of admirers with films like Faces Places and The Beaches of Agnès.

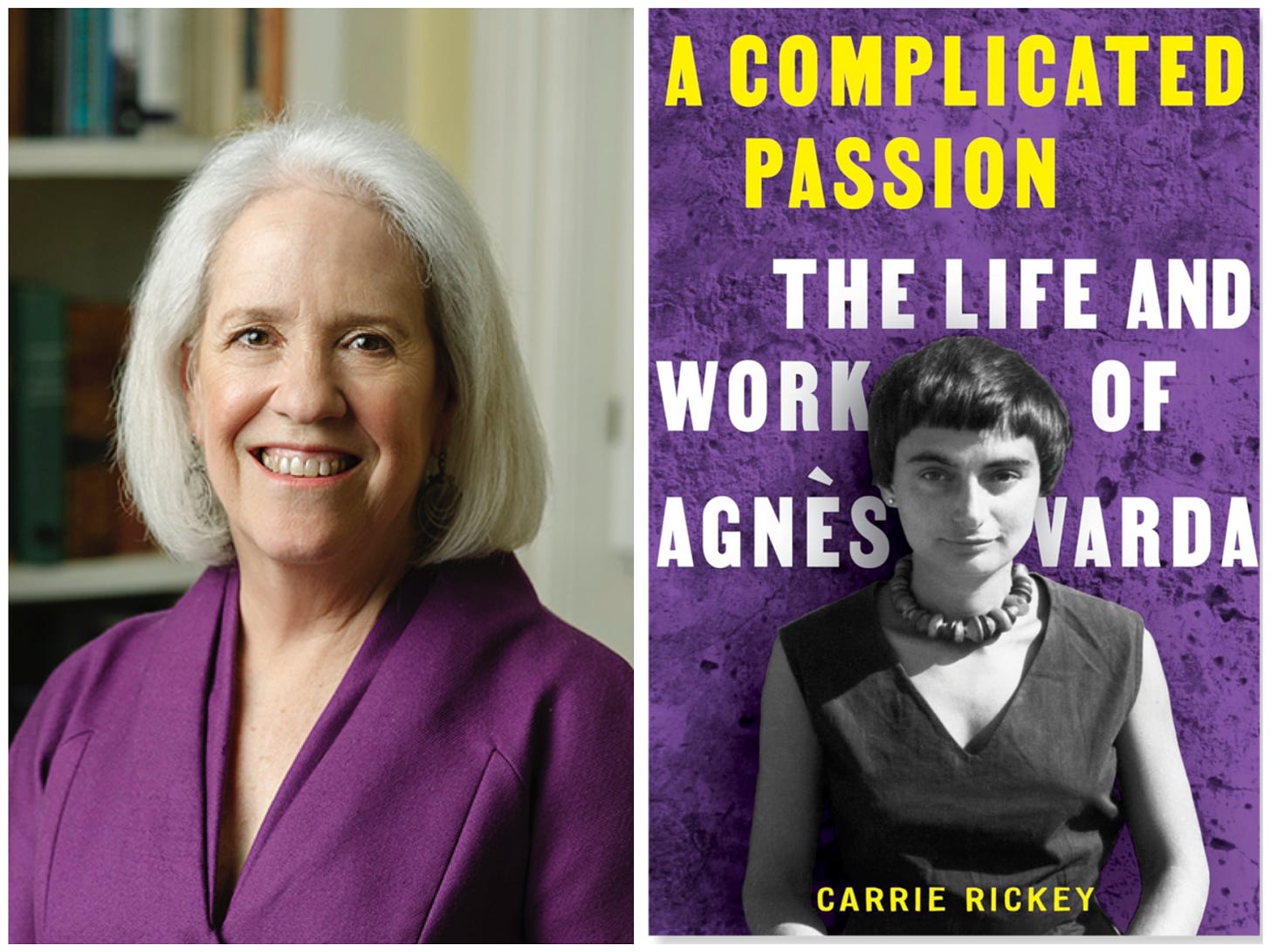

In her sharp and informative new Varda biography A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda, Carrie Rickey recalls her first encounter with Varda’s work as a student as the first time she realized a woman could direct a movie. As a film critic for The Village Voice and The Philadelphia Inquirer, Rickey witnessed the evolution of Varda’s career and the not-entirely-coincidental changes in the film world that have helped open up—if not yet open wide enough—opportunities for female filmmakers in the decades since Varda first stepped behind the camera. That story plays out in the background of Rickey’s revealing book, which follows Varda from a childhood disrupted by World War II to her later years as a global icon. In between, Rickey follows her through trips to China, Cuba, and Hollywood and chronicles her relationship with fellow filmmaker Jacques Demy, which spanned 1958 until his death in 1990 (they married in 1962). Demy’s AIDS-related death, and their periods of separation, did not become public knowledge until years after his passing. For as much as Varda made herself the subject, she didn’t always tell the whole story. We spoke to Rickey about the book, women in filmmaking, the films Varda never made, and more.

Varda wrote a memoir and she covered her life pretty extensively in her later films especially. Were you at all worried that the story had already been told?

Varda was very selective in what she shared. She was, I think, congenitally non-chronological. It was hard to understand if there was any cause and effect to her life. Her memoir is charming and funny and sometimes confessional, but I think it deliberately wanted to skate over certain parts of her life. There’s really nothing about her family, for instance, except for her mother, as though she gave birth to herself. Which she did.

But I didn’t know that when I started. I wanted to use her as an example of the difficulty of establishing herself as a female filmmaker in, as we used to call it, a male-dominated industry. She had the longest career, 65 years, and was certainly one of the more experimental filmmakers among women and men.

I grew up in the 1970s reading about feminism, but seeing movies largely with and about men. And I love those movies. I love The Godfather, I love The Conversation, I love Mean Streets, I love Star Wars. But basically, except for Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia and Diane Keaton as the wife and The Godfather who gets the door slammed on her at the end, there weren't a lot of important female characters in movies. The women I knew all had cognitive dissonance because we were fighting for equality and just not seeing ourselves—a little more in French and European cinema, but not a lot more.

Then the more I learned about film history, the more I learned how many women there had been in the silent era and they’d, for the most part, been erased. And I had never even heard of Alice Guy-Blaché until the 1990s. I was a film scholar! I’ll give you this, just this stat: in 1917, Universal Studios, which was the first studio that consolidated, had seven women, seven important female directors working for them. And in 2017, a hundred years later, they released exactly one movie, totally directed by a woman and one movie directed by a male/female team. So in those hundred years, things seem to have gone backwards.

One of the most striking details in your intro is when you talk about watching Cléo from 5 to 7 in college in the ‘70s and it was the first time you’d seen a film directed by a woman.

Well, I didn't know. I was 18. I think in the book, I say I was 19, but I realized I had just turned 18 in November before that January class. I had no idea. And I just cried. I guess I knew that women could be journalists. I followed Brenda Starr in the comics. But it was a time when I was thinking about what I was going to be and I just didn't know, and that was very surprising. Later, I guess in the 2000s, when women continued to be basically shut out of the top tiers of filmmaking, I called the Bureau of Labor Statistics in Philadelphia and I talked to one of the researchers there and I asked, “So what are your stats on female filmmakers?” And she said, “Let me get back to you.” She called back about two hours later and she said, “Wow, I had no idea that now we have two professions, coal mining and directing, where women are below 5%.” I started laughing and she said, “Do you know any reasons why this is so?” And I kind of explained, but how do you explain to a statistician that combination of sexism, history, niche marketing and all these things that led to women largely being shut out? So all those feelings informed the book. And I was hoping that, through Varda, I could tell the story of why that happened.

I’ve always thought of Varda as quintessentially Parisian. But she really was quite the outsider to Paris and lived a very peripatetic existence early on. Do you feel like that informed her view of the world or her work in any way?

Well, she was very short. She was not, we'd say, conventionally beautiful, although she did presage a kind of a 1950s Bohemian look, the gamine. And she didn't like Paris when she got there. Although she was born in Brussels, she really loved it when her family moved to Sète in southern France because she could be outside the whole year. It was very temperate and she loved the old fishermen there who told her stories and taught her how to mend nets. And she met her spiritual family the Schlegels in Sète, these daughters of artisans who lived nearby the boat she lived on.

Living on a boat was kind of weird. Most of Varda’s family didn't swim and her mother lived in horror that one of them would drown. I found out later, after the book was done, Varda always had to wear pants and stuff underneath her dresses to keep warm while getting on the boat. She was very outdoorsy, and Paris wasn't. When they moved there, they basically had to move because they were chased out by the Germans who were coming to the free zone and wanting to take over and wanting to take their boat away so they could use it. She really didn't like disruption. I mean, when she found her house, she lived in it for almost 70 years and she really liked having a home base.

I didn't realize that at first. But the house you see in Daguerreotypes turns up elsewhere, too.

It's the same house. It was a cheese store and a framing store next door to each other. She bought these two properties next to each other situated around a courtyard and there was no plumbing. She really did a lot of the work herself. She knew how to build things. Her father was an engineer, and although she hated him, she must've learned a lot of things from him. He made inventions for transporting foodstuffs and fruits and vegetables, which were on tracks and involved cranes. I don't know if Varda learned about that equipment while she was growing up or whether she just understood it, but she had a lot of tracking shots and she did a lot of crane shots. When I was reading her father's patents. I went, “Holy shit.”

She had a really interesting life. I don't really stress this in the book, but she married a bisexual man and I think her first sexual experiences were with a woman, Valentine Schlegel, a daughter of this spiritual family, she met in Sète. I think for some reason she really felt a need to hide all that and suppress all that. And I thought, “God, in this day, who cares anymore?” I don't make a lot of it in the book. I think her gender had something to do with her movies, but I don't think her sexuality had much to do with it. I don't basically see a male gaze in her movies.

But interestingly, Cléo was initially supposed to be about a man who had cancer, and Vagabond was initially supposed to be about a male drifter, but she changed the genders as she went along. And I thought, “What does this mean?”

Circling back just a little, La Pointe Courte was made years before what used to be considered the first French new wave film. Yet she was referred to as the “Grandmother of New Wave” and similar titles.

And she's the same age as almost all the other guys and about eight years younger than Alain Resnais.

I feel like obviously her reputation is better now than it's ever been, but do you think her role within the French new wave is now more fully appreciated?

I think now, certainly. By 1965, historians basically said she was the start of the new wave. And I think the problem she had with the “Cahiers boys” was she made a movie before they did. Her father had died and she had $14,000 that he left her, and she could make a movie with that. And she got there first because she had money. And she was experimental. Although the only schooling she finished was her certificate in photography. She dropped out of the École du Louvre. She only wants to audit classes at the Sorbonne because she doesn't like taking tests. But when she decided to be a photographer, she did it. She mastered it, and I guess she felt that if she could master photography, how hard could cinematography be?

This was very much her attitude toward a lot of things, right?

She was a can-do kind of woman. And when Truffaut reviews La Pointe Courte, he makes a little cruel joke about how the director cast a lead actor who looks like her. Which is really mean. They were always taking swipes at her, so she's got to be a little bit defensive. Truffaut later recanted all of that, became a friend of hers, and did very much want to produce a movie of hers. If you read in Truffaut’s correspondence, he talks about this movie called La Mélangite, which means “mixitis.” It's supposed to describe a malady of someone who mixes up places and memory. I can't remember who he's writing to, but he’s saying how positively frightening and creepy the script is, but there's nothing like it. It's a hilarious letter about her concepts, which he really is impressed by.

Varda’s sister-in-law, Jacques’ kid sister, who loved Tuffaut and whom Truffaut really liked a lot said, when Truffaut used to visit, Agnès and Truffaut would talk producing all the time, and Jacques would walk out of the room. Jacques didn't care about producing, he just cared about making. But Truffaut and Agnès were really interested in the financing and more, they were both more pragmatic than Demy, and they wanted to know about the financing too and the distribution.

She understood branding. The Ciné-Tamaris logo is very memorable.

She branded herself like Hitchcock. She commissioned caricatures of herself like Hitchcock did, and she had the hair, the two-tone hair. One of her friends that I interviewed said she just loved being recognized. My favorite thing that I found out was that she was the only independent filmmaker who could read a royalty report and find the mistakes and get more money.

You note in the book that when a lot of filmmakers of her generation were lamenting the death of film, the switch to video, she just ran with it. What was it about her that made her have that impulse in her?

She was very practical. Making movies is expensive with film. When her son suggested she pick up this digital camera, she thought, “God, this is lighter than the view camera I used to use as a photographer.” She also knew that she wanted to make more of the essay films, and the problem with being behind a 16mm camera is that, when you're making it, when you're shooting it yourself, you can't see the person, really see the person, you're talking to. For some of her essay movies, she did her own camerawork and she realized if she had the digital camera, she could see her subjects and get more intimate with them.

That's why The Gleaners and I is such a revelation. She's getting so up close and personal, as they say, with these marginal people, and she has such empathy and they're able to really communicate. Gleaners might be her ugliest movie. She was just learning how to deal with digital, but the humanist component of it is very, very powerful, and its subject is very powerful. I mean, sure in America, Michael Moore was making these essay films too, but they were about him. The Varda movies are about other people or about other people as well as her. I think it was totally a practical decision. She produces the movie herself. It's not an expensive movie to make. It's like a travelog. She has a friend who can handle a camera, shoot her in her scenes, and she makes it for not very much money. And I think it's one of her most commercially successful movies.

The book references a lot of unrealized projects. Which would you most like to have been able to see?

Oh, La Mélangite. But I don't think it was actually doable. I would've liked to see Peace and Love, which is the one that she was going to make for Columbia. I think that at a certain point in the early ’80s, after making all these very small documentaries that really didn’t get distribution… And they're good. Mur Murs and Documenteur. I grew up in L.A., so those movies are really important to me. The L.A. mural programs, which were wonderful, and no one in the city was writing about them. It was so exciting to just be able to walk around Venice or downtown and see these fantastic murals. It was really the museum without walls that André Malraux was writing about.

What happens to her before Vagabond is she realizes, I don't really want to write scripts. I really feel that, as Michelangelo said, you can find the sculpture in the block of stone. She felt she had to have a lot of footage in order to find what the film was about. I mean, Vagabond was originally about plane, tree disease! Yeah. Then when she went out to do the research, she said, “Now this other thing is happening.”

What do you think her remake of Cléo from 5 to 7 with Madonna would have looked like?

Madonna's mother died very young of breast cancer. I'm guessing it would've been more of a mother/daughter story. Madonna wanted it scripted. Varda said, “No, let’s just do it.” Varda wanted to do it more freely like one of her essay films and then put it together. I don't think they could agree on that. So I think that's why it didn't happen. But Madonna later said, and maybe this was just to make Varda feel better, “I should have done it Agnès's way.”

Everyone knows Cléo from 5 to 7, Vagabond, The Gleaners… maybe Le Bonheur. What’s a lesser known Varda film you’d recommend?

I love her shorts. I think her shorts are fantastic, and I'm very fond of “The So-Called Caryatids." It’s 12 minutes long, but it's about so many things. She got a commission from French television to make an episode in a series they were doing about the nude in art and architecture. So she goes out and she makes a movie about all these caryatids, the female human columns, like at the Acropolis. And she kind of was wondering why all the caryatids are, kind of naked and exposed and their male counterparts, the Atlases, all show signs of strain and they're draped. We don't see their manhood, but they're powerful. But the women are kind of basically like women in Hollywood movies, therefore their nudity is for titillation, and it makes female work look casual and unimportant, unlike male work. It doesn’t ask it, but suggests questions. Why are men portrayed as having this power? They work hard, and females are decorative, and when they carry weight, it's on their head and they're pretty when they do it. It's just, it's fun. She found a way to make movies that were edifying but entertaining.

A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda is now in stores.

Great interview! I look forward to reading the book and being inspired to revisit all of Varda’s films. THE BEACHES OF AGNÈS was a key film for me when I got to see a screening of it on campus.

I didn’t know about Varda’s relationship with Demy. Does anyone have recommendations on books that cover French cinema history? A survey from Renoir to current would be great, but I’d be open to something like an Easy Riders, Raging Bulls that covers the French New Wave.