#72 (tie): ‘My Neighbor Totoro’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Hayao Miyazaki's second film on the list after 'Spirited Away' is the ideal gateway into his work for the younger set. Or anyone else, for that matter.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

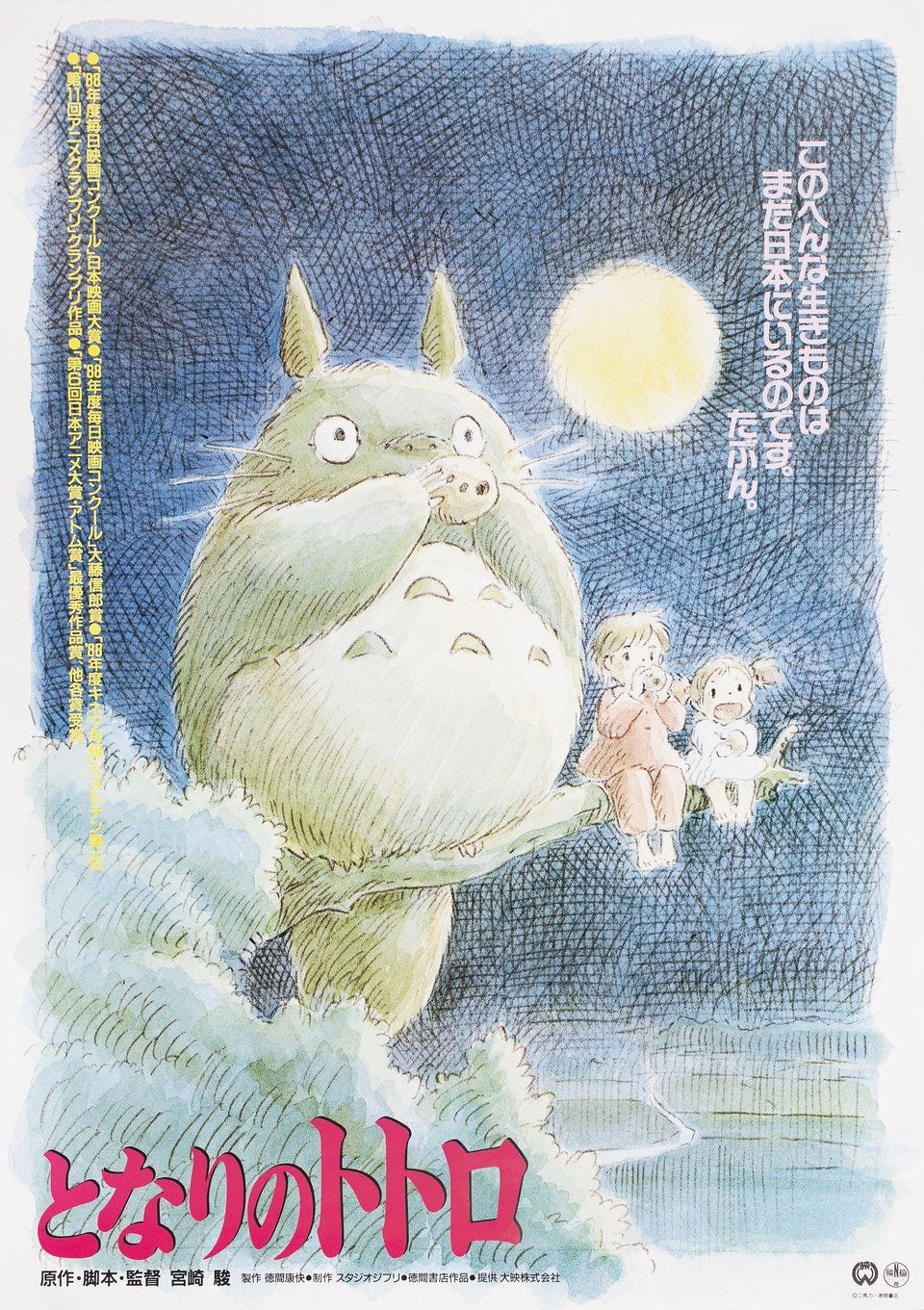

My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

Dir. Hayao Miyazaki

Ranking: #72 (tie)

Previous rankings: #164 (2012)

Premise: Accompanied by his two daughters Satsuki (voiced by Noriko Hidaka in the original Japanese language version and Dakota Fanning in the 2005 English dub and Mei (Chika Sakamoto / Elle Fanning), Tatsuo, a professor, moves to the Japanese (Shigesato Itoi / Tim Daly) countryside. Though Tatsuo remains unfailingly cheerful around his daughters, the family has made the move to be near the hospital where the girls’ mother Yasuko (Sumi Shimamoto / Lea Salongo) is recuperating from an unnamed illness. While settling into their semi-dilapidated new home, the girls encounter tiny, dust-like spirits. Soon they’ll encounter other, bigger spirits that reside nearby, including a trio of furry creatures, the largest of which Mei dubs “Totoro” after a troll in her picture book. As they adjust to their new life, they wait for news of their mother’s recovery.

Keith: Scott, I know that, as with Spirited Away, we’ve both seen this movie many times. That’s because it’s great and we have excellent taste but also because we are parents and Miyazaki has made some of the greatest kids movies ever. (Just don’t make the mistake of forgetting how violent Princess Mononoke is and trying to show it to your kid before she’s ready. That does not go well.) When you’re repeatedly exposed to the same film, you tend to notice things you missed before, or at least appreciate moments that might not have stood out on previous viewings. This time, I found myself taken with the moment after the girls encounter Totoro while waiting for their father’s bus in the rain. They show him how to use an umbrella after which he boards a bus that’s shaped like a giant cat. Or a cat shaped like a bus. Either way, it has to be one of the strangest sights either girl has seen but, Then, after the Catbus pulls away, Satsuki says only (in the subtitled Japanese-language version), “He took Daddy’s umbrella…” After all they’d just experience, this is the detail on which she fixates.

It’s funny, but it’s also perfectly in keeping with the rest of the film and its depiction of how kids see the world differently from adults. Near the beginning they’re told by Granny (Tanie Kitabayashi / Pat Carroll) that she used to be able to see the dust spirits, the implication being that the ability to see such creatures fades in adulthood. Granny’s nonchalant about this, and though the rest of the film depicts this divide — only the girls see Totoro and his companions — there are no scenes in which disbelieving adults dismiss them. (Also, do the other creatures have names? Little Totoros?)

My Neighbor Totoro is a film of many porous borders: the divide between nature and humanity, between childhood and adulthood, between dreams and reality, between the supernatural and the natural. In one of my favorite sequences, Totoro and his two pals visit the girls’ newly planted garden. When the girls join them, the garden starts to grow and grow and grow, joined by a giant tree. When they wake up the next morning, their garden has sprouted but everything else has vanished. It was all a dream. But, that’s no big deal! That doesn’t make what happened unreal, just an extension of what actually happened.

There’s a telling scene in which Mei tries, and fails, to bring her father and older sister to Totoro’s home within a tree. As part of the search, Tatsuo has to hunch to follow Mei and Satsuki through a tunnel of vines and branches he would never have noticed if they hadn’t brought him there. He may not see exactly what Mei wants him to see, but he makes the effort and he’s rewarded with a glimpse of the world from a different perspective. I think, in some ways My Neighbor Totoro makes adult viewers into Tatsuo. But I know it plays differently for children because I’ve witnessed that. So why does it work for both audiences, Scott? And, pulling back a little further, why does this sedate, virtually plotless movie work at all? The default move for a lot of kids' movies is to make sure the viewers never get bored by throwing a lot at them at all times. This moves at a different pace than, say, a Minions movie, doesn’t it?

Scott: Quite so. And you know what? It doesn’t matter.

As I wrote in our discussion of Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro was a truly revelatory moment for me as a father, because it defied conventional wisdom in terms of what my child might like—or even tolerate—at an early age, based on the assumptions that American animated films had ingrained in me about how films should operate. Yet we rolled the dice on My Neighbor Totoro early and it immediately became my eldest daughter’s favorite movie, and kicked off a passion for Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli that endures to this day. Things that might have seemed estranging about it—the pacing, the animation style, the internal logic, the dialogue that hasn’t gone through multiple punch-up sessions, etc.—are sometimes less perplexing to kids than they are to adults, who can struggle more with abstraction. (I recall a favorite line from Duck Soup where Groucho’s Rufus T. Firefly, when asked if he understands a document, says, “Clear? Why a four-year-old child could understand it!” and then whispers to an aide, “Run out and find me a four-year-old child. I can’t make head or tail of it.”)

That said, My Neighbor Totoro is certainly starter-level Miyazaki, appealing to the very young in ways that, say, Princess Mononoke and The Wind Rises may not. (See also: Kiki’s Delivery Service and Ponyo, also good for the tykes.) The key is how closely Miyazaki gets his audience to identify with Satsuki and Mei, and allow them to be our curious and enthusiastic guides through a world of wonder. Just like Spirited Away, the film opens with children moving to a new place, only these girls do not seem as bummed about it as Chihiro in Spirited Away, though they have reason to be worried. Their mother is in the hospital for an unspecified illness—that we’re never told exactly what is a small masterstroke, given how kids are often shielded from difficult news—and they’re moving to an awfully rustic country home with their father, who’s probably doing his best to cover up his own anxiety about it. Yet the girls love their “wreck” of a house, which they’re excited to believe is haunted, and they’re unphased by the black “dust bunnies” (or “soot spreaders”) that scurry along as they enter the place.

You mentioned this already, but I do love how the adults in My Neighbor Totoro accept the outlandish occurrences in the film just as much as the children do. You mention the scene where Mei excitedly shows her sister and her father the forest path that led her to meet Totoro, but is disappointed that the same path leads back to where they came. Mei assumes that her father won’t believe her and immediately starts protesting that she wasn’t lying about it, but he waves her away. “You probably met the king of the forest,” he says. “You were very lucky. He doesn’t come out often.” The Granny, too, remembers seeing those adorable dust bunnies when she was a kid, and correctly predicts that they’ll go away once they see a happy family occupying the space. It’s serenely understood by everyone that the natural and supernatural co-exist in this place. Miyazaki almost casually erases a border that’s firmly established, even in other animated works.

One sequence that really stood out for me this time happens before the great Catbus appearance, which occurs at the end of a fraught day when the father has left town for work, Satsuki is in school, and Mei is under Granny's care for the day. Satsuki is sitting down for an assignment–and getting stares from the neighbor boy Kanta (Toshiyuki Amagasa/ Paul Butcher)—when she sees Granny and Mei outside the window. Mei’s cheeks are streaked with tears. Granny explains that the girl insisted on being with her sister and Satsuki brings Mei into class for the rest of the day, and the little girl doodles contentedly. Nothing is said about why Mei is crying because nothing needs to be said: She misses her mother and she can’t handle those emotions without her father or sister by her side. Later, Mei will go to incredible lengths to bring an ear of corn to her mom at the hospital. But it’s such a lovely, underplayed dramatic moment that suggests the depth of uncertainty and despair this family is feeling, despite their optimistic spirit.

What do you make of the way the mother’s illness is treated, Keith? This would be another recurring theme in Miyazaki’s work, connected to his memories of his mother’s years-long struggle with spinal tuberculosis, which frequently kept her in a sanatorium. As I say above, I like the vagueness of the diagnosis where the children (and us) are concerned, and I also like how the weight of her absence is felt, not just through the letters that Satsuki writes her or Mei’s journey to see her, but in the fabric of the movie itself. My Neighbor Totoro is not a melancholy film—quite the opposite; it’s magical and delightful–but the sisters’ experiences do have this fraught context.

And what about the visual and musical texture of this film, too, Keith? I’m not going to say this is Joe Hisaishi’s best score, but I’m not not going to say it, either.

Keith: Hisaishi has over 130 score credits listed on IMDb dating back to the 1970s (and it’s only now that I put together that he also scored films from the prime of Takeshi Kitano’s directing career) so I won’t make that claim. But that doesn’t mean you’re wrong. It’s almost easy to overlook the role it plays in setting the mood of the film. Hisaishi never nudges Totoro to a more intense pitch. Even when Mei disappears and is (briefly) feared dead, the music doesn’t oversell the moment. It’s the most dramatic event in the film—apart from, you know, all the spirits and magic and such—but pushing it too hard risks cheapening the film. The world of Totoro is one in which peril isn’t unknown but the worst never happens.

Or at least that’s how I’ve always read it. That the girls’ mother doesn’t die plays a bit like the pistol introduced in the first act that isn’t fired in the third, doesn’t it? That’s not a complaint. It’s just another way Totoro is unlike other movies. It’s true to life in the sense that Miyazaki’s mother received treatment for eight years but lived until the age of 72, years after her medical condition stopped being an issue. But it’s also true to life in that this is sometimes how health crises play out. They’re scary and especially tough for children to understand, but they don’t all have tragic endings. That’s part of why I like the scene of Mei in the classroom you mention above. Her sadness and confusion go hand-in-hand. She can be the happy, enthusiastic kid of earlier scenes, then get overwhelmed by events and emotions that are beyond her experience and understanding.

Scott, we’ve talked a lot about the kids in this movie and that’s fair, because it’s their story. But what about the creatures? In typical Miyazaki fashion, everything in My Neighbor Totoro is rendered in exacting detail, from the countryside to the period-accurate bicycles to the semi-dilapidated interior of the family’s new home. That extends to the film’s magical creatures. I almost called them “visitors from the spirit world” but that’s not exactly accurate. Closely related to beings from animistic folklore, they're tied to the rural region to which the girls move. They look like they belong there, none more than Totoro, who truly fits the part of a king of the forest, albeit a gentle one. He has claws and teeth but he’s soft and welcoming.

The character design here is almost magical, for want of a better word. Totoro and his companions are fantastic but also grounded, as if Miyazaki started with the idea of a big, friendly fur monster, then worked backwards to give it believable anatomy. But he’s not so strict about staying plausible that he doesn’t let Totoro’s face erupt in a big, toothy grin that defies anatomy. It’s animation, after all. You can do that sort of thing. That said, I don’t think the Catbus’ anatomy makes any sense at all but who cares? The headlight eyes, the way it bounds on its many feet, its “door,” the rat tail lights: What an amazing creation! I know we don’t want this discussion to devolve into a Chris Farley Show-like list of cool stuff we think is cool about the film, but remember the first time you saw the Catbus coming out of the forest and you couldn’t believe what you were seeing? That was awesome.

Out of curiosity, I went back to have a look at how this film was received in America upon release in 1993. That version—released by Troma, of all outlets—features a different dubbed soundtrack that’s been lost to time, but I don’t think it’s different in any substantial way. (It’s the first version I saw, on VHS.) It’s funny how some reviewers can be perceptive about what the film’s doing but also very wrong about whether or not it works. The New York Daily News review written by “Phantom of the Movies,” suspects:

“It’s unlikely that Totoro will score as heavily here. For starters, the cryptic flying-cat critter who lends young sisters Satsuki and Mei a helping paw takes a backseat to the narrative’s more mundane detailing of the girls’ adjustment to a new neighborhood.”

So close to getting it! (Though the Phantom’s conclusion that it’s “an expanded version of the kiddie programming found on Saturday morning TV” could not be more wrong.)

Others were more tuned in. In the L.A. Weekly, Gloria Ohland wrote of its “reverence for nature and the spirits who reside there.” Yet even its champions could be a bit thrown off by the differences between the film and more familiar animated styles. In the Los Angeles Times, Charles Solomon’s positive review wrote that the “animation never rises above the level of Saturday morning kidvid.” I think a lack of familiarity with anime — or an association of it with “kidvid” — can explain that complaint, but it’s curious to remember just how different this film was to American eyes thirty years ago and how beloved it is now. So let me hand it over to you with a related question. Does that surprise you? Films from other countries have an uphill battle in the U.S. even when they’re not subtitled. Animation has often had a tough time with critics. Yet in 2024 Totoro is both a beloved kids movie staple and a canonical classic (hence its presence on this list). And one more question: Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro are the only Miyazaki films to crack the top 250 on Sight & Sound’s list. Any thoughts on why these two?

Scott: I had never seen or even heard of a Miyazaki film until Siskel & Ebert reviewed My Neighbor Totoro on their show. Roger liked it, Gene didn’t. (Gene saw the light later with Kiki’s Delivery Service.) And obviously the clips they showed made such a huge impression on me that I remember the segment, which isn’t currently available online. I believe the Catbus made an appearance and Totoro almost certainly did, and how can you not immediately recognize those creatures as special? I think Ebert was also hip to the particular rhythms of the film, though again, my memory isn’t perfect. And hey, if you want more prominent cluelessness from American critics, you also have this lede from The New York Times’ Stephen Holden:

What will American children make of "My Neighbor Totoro," a Japanese animated film whose tone is so relentlessly goody-goody that it crosses the line from sweet into saccharine?

It reinforces the point that I made earlier in this discussion: Adults don’t always know what American children will like and often guess incorrectly. That’s why we have animated forest creatures making crude references or talking like aggrieved fortysomethings. A phrase like “relentlessly goody-goody” mocks what would have made Miyazaki and My Neighbor Totoro unique: A gentler approach to the conflict that’s usually the engine of American narratives, which here results in a family united in addressing the hardships and wonders that come their way. Mei going missing at the end of the film is really the only urgent crisis here; the others, like the mother’s illness or the challenges of settling into a new and strange place without her, are kept at a low simmer. That the adults believe Satsuki and Mei’s stories about the creatures they encounter is refreshing, not goody-goody, because it’s one of the many expectations Miyazaki defies in his own version of family entertainment. And to hear the film described as “saccharine” makes me cringe a little: Mei leaving an ear of corn marked “For Mother” on the hospital windowsill is such a small, lovely gesture. Who could roll their eyes at that?

As for the “kidvid” look of the film, we can safely scoff at that, then and now, but My Neighbor Totoro came along just as Disney animated features were coming back from a long fallow period—it was released in the U.S. after The Little Mermaid, but produced before—and I don’t know if critics could really know what “good” animation looked like at the time. Even in that Kiki’s Delivery Service review, Ebert uses the word “cartoon” to describe the film, which is not the sort of language we use today. There’s also a ramp-up in sophistication between this and Miyazaki’s later work, which would have been beyond insulting to talk about as a “kidvid.”

As to your question about why Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro are represented on the Top 100 while his others fall outside the Top 250, my glib response is that movies have been around for over 125 years and a lot of quality work has been made in that time. But honestly, I think those two films both underline Miyazaki’s importance as a master of the animated form and speak to his ability to work at different registers. The audience for Totoro is not precisely the same as that for Spirited Away—as I wrote about earlier, the former (along with Kiki and Ponyo) seem aimed at a younger crowd—and the “creatures” in Spirited Away have a sophisticated mythology that the more simplified Totoro disposes. (Totoro is the “king” of the forest. The Catbus is a Catbus. Pretty easy to understand.) This is a discussion for another time, but the way consensus builds around specific titles for a poll like Sight & Sound depends so much on whether one or two films by a director really stand out. (You’d probably call Paul Thomas Anderson, for example, one of the most important American filmmakers of his time, yet nothing of his even sniffs the Top 100. I think it’s because there’s no obvious consensus choice.)

To loop back to Hisaishi, his prolificacy and stature reminds me so much of Ennio Morricone, whose work was strongly associated with Sergio Leone, but who composed scores for many, many other filmmakers—some well-known, some quite obscure. (He’s well-known enough that I was intending to pick up tickets for his recent concert appearance in Chicago but bailed after discovering they were wildly expensive. Go get that bag, Joe!) It’s funny how much Hisaishi’s scores for Miyazaki and Takeshi Kitano work to similar ends, at least insofar as Kitano’s brutal gangster movies are leavened by moments of whimsy and even sweetness. Here, Hisaishi offers bright, bouncy notes to cover the light comedy and the more sweeping, emotional passages as well, which you can hear in this orchestral version of “Path of the Wind.” Maybe he’slike Morricone in that he created a lot of excellent work, but seemed to deliver to a higher standard with Leone types like Miyazaki and Kitano.

And that does it for animated films on the Sight & Sound Top 100. Two from Miyazaki and that’s it. How do you feel about that, Keith? And what are we going to do next?

Keith: It had never occurred to me that Miyazaki’s movies would be the only representations of animation on this list. I don’t know if there’s any film on the list solely because of historical importance, but there are several you can point to as form-changing breakthroughs without which the list would feel incomplete. Does it seem weird to you that even Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs isn’t on the list, to say nothing of Fantasia or Toy Story? Is it just another example of animation not getting its full due?

I’ll let that question hang in the air for now as we plunge ahead. And where, you ask, are we plunging? We’re going back to Italy for, appropriately enough, Roberto Rosellini’s Voyage to Italy. Grab your passports and join us.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#75 (tie): L’Avventura

Apropos of this, Alan Booth was an English expat living in Japan in the 80s (whose Roads to Sata is a minor travelogue classic) and also the film critic for the English language Asahi Evening News in the 80s . For completeness, his comments on Totoro (made in passing for a slightly disappointed review of Kiki’s Delivery Service) from 1989 - which is probably the earliest English language review of it :

“Not all readers will agree, but I feel the most serious mistake I have made in the eleven years since beginning this column (apart from beginning it at all) is not to have reviewed last year’s animated blockbuster, Tonari no Totoro. The mistake was doubly serious since the film’s director, Hayao Miyazaki, had established a very respectable track record with his two previous full-length animated features, Kaze no Tani no Naushika and Tenkū no Shiro Laputa, the first of which in particular had been both a runaway success at the box office and a cult item akin to the Ginga Tetsudō films of Reiji Matsumoto. My four-year-old daughter and I have since watched Tonari no Totoro so many times on video that I have completely lost count of them and I still think, as I did when I first sat enchanted by it, that it is one of the finest animated children’s films ever made. It has a magic not easily conveyed in words, and I fully expect to be watching my copy until every inch of image has been rubbed off the tape.”

I’ve seen Hisaishi live in concert performing his Studio Ghibli music twice, and it is a fantastic experience. He doesn’t have a weak soundtrack among the bunch, although maybe PORCO ROSSO and PONYO are borderline. The rest are sublime. I don’t know why SPIRITED AWAY made the Sight & Sound list, but I know why TOTORO did. It’s Miyazaki’s best movie. That Totoro’s profile became Studio Ghibli’s logo shows just how much this movie means to Miyazaki. Great observations here, Keith and Scott. I also started showing TOTORO to my daughter when she was very young and she also loved it and has subsequently watched every Miyazaki movie. She actually watched PRINCESS MONONOKE when she was pretty young and it’s now her favorite Miyazaki. I went to a screening of TOTORO at the Museum of Modern Art in 1999, and I was disappointed to see in the program that it was the English-dub version. Then suddenly, Miyazaki himself appeared in the room, walking up the aisle to the front, and stated that he had brought the film reels in the original Japanese to New York because that’s how it should be seen. People went nuts.