#72 (tie): ‘Journey to Italy’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

A married couple's trip to Naples leads to some unexpected realizations in a Roberto Rossellini film starring George Sanders and Ingrid Bergman.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Journey to Italy (1954)

Dir. Roberto Rossellini

Ranking: #72 (tie)

Previous rankings: #41 (2012), #86 (2002), #32 (1992).

Premise: Alex (George Sanders) and Katherine Joyce (Ingrid Bergman), a married couple living in England, travel to a villa outside Naples after inheriting it from Alex’s uncle. As the film opens, Katherine remarks that they haven’t really been alone together since their wedding. It soon becomes clear that they’re uncomfortable with this situation and that the marriage, though outwardly companionable, has some cracks. Those cracks start to turn into fissures after Katherine reveals that a man named Charles, a childhood friend who died two years before, shared poetry inspired by his time in Italy with her and even came to her window the night before their wedding despite his illness. In the days that follow, each explores the region alone. Alex strikes up a flirtation with a woman after traveling to the nearby island of Capri. Katherine finds herself profoundly moved by visits to the Naples Museum, a nearby volcanic field, and an ossuary with stacks of unidentified, centuries-old dead. As the film draws to a close, the couple visits the ruins of Pompeii together and reach a decision about their future.

Keith: I can thank Martin Scorsese for a lot, including introducing me to this film via his 1999 documentary My Voyage to Italy. Like its predecessor, A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies, the film has fallen out of circulation, which is a shame because I can think of few better ways to discover a bunch of great movies than through Scorsese’s enthusiastic analysis. I can’t say I’ve gotten around to every film Scorsese recommends over the course of the four-hour film, but his love for My Voyage to Italy made it seem like a movie I had to see immediately. Having seen other Rossellini films, specifically the trilogy he made after World War II that helped define Italian neorealism, I thought I knew what to expect, but this was really nothing like those, in either subject or style.

The most immediately striking element was Sanders’ performance. He’s arch, witty, and dismissive, delivering sarcastic comments and talking about “disposing” of the estate quickly. He’s also the furthest from the non-professional actors I associated with Rossellini’s work. So, too, is Bergman of course, but she delivers a much different sort of professional performance, the kind defined as much by the emotions that flash across her face as the dialogue she delivers. They’re not acting styles that naturally fit together, but I think that’s part of why the movie works so well. These are characters with strikingly different ideas about what the world is and how it works.

Voyage to Italy began as an adaptation of the Colette novel Duo, which I’ve never read. But I have read James Joyce’s “The Dead” many times and the couple’s surname is no accident. In that story, the protagonist, Gabriel, has his notion of who his wife is—what life is, really—when she tells him the story of a boy who loved her and died young after insisting on meeting her in the rain. But “The Dead” is really just a jumping off point for the movie. That revelation occurs at the end and the story is locked into Gabriel’s perspective. Voyage to Italy is effectively two stories that intertwine. I found myself thinking of another literary connection, too: A Room with a View, another tale of characters from northern climes who see in Italy everything their lives lack: expressiveness, passion, spirituality. (On the movie front, I’m not sure Eyes Wide Shut would be quite the same without this predecessor either.)

Scott, I know this is your first time watching this movie. (No shame in that. I have even more embarrassing blind spots we’ll hit a little later in the list.) Did it match your expectations of a Rossellini film? Were you as struck as I was by the differences between Alex and Katherine’s respective voyages to Italy? Each is remarkable in its own way. Alex takes a baby step into a world of romantic and sexual freedom and discovers it’s not what he expected. Katherine finds herself overwhelmed by a landscape filled with sharply contrasting images from the past, from vibrant statues to stacks of bones. What about the way they come together? I almost want to hold off on talking about the ending because, phew, what an ending!

Scott: Like you, my experience with Rossellini had previously been limited to his neorealist films, specifically the trilogy of Rome,Open City; Paisan; and Germany, Year Zero, the last of which I found particularly bleak and affecting. (And shares a connection to Voyage to Italy in focusing on the ruins of civilization, albeit a much more contemporary one in the earlier film’s case.) I have not seen either Stromboli or Europa ‘51, the two other major films Rossellini made with Ingrid Bergman that appear to be precursors to Voyage to Italy, so I can’t say how much they signal a transition from one phase of his career to the next. From what I gather from other sources, Voyage to Italy is the biggest leap forward into a different kind of filmmaking for Rossellini and for global cinema at large, but I’ll leave that to the experts to discern.

All that said, I’m not so sure there’s as much of a distance in Voyage to Italy between the neorealist Rossellini and the modernist who paved the way for directors like Michelangelo Antonioni and the French New Wave. (Sidenote: How convenient that Voyage to Italy and Antonioni’s L’Avventura are tied at #72 in the poll. They pair so perfectly.) But I disagree with your assertion that Voyage to Italy is nothing like those earlier films, because it strikes me so much as a link between movements, inching Italian cinema forward from the street-level, documentary-like backdrops of the country just after the war to a style that reflected the uncertain and turbulent interiors of characters like the Joyces. One of my favorite things about the film is how much Rossellini opens up the frame to ordinary Italian life, particularly the hustle-and-bustle of Naples, which affects the couple in different ways. (“What noisy people,” complains George as the film opens. “I’ve never seen noise and boredom go so well together.”) It’s not for nothing that the film’s emotional ending is situated within an Italian street procession, which is so much more chaotic and stormy than the buttoned-down lives of these monied Brits.

The old Rossellini touch is also evident, I think, in how much the film draws from its beautiful setting without being anything like a travelog. Shooting in the stark black-and-white that carries over from his neorealist films, Rossellini is visiting an area that would be self-evidently gorgeous in color, with the terrace views of Mount Vesuvius, the Tyrrhenian Sea, and the countryside outside Naples, not to mention what George sees of Capri when he goes off on his own. But Rossellini is careful not to overwhelm these characters with this sensual ambience, and the sights that Katherine visits, for example, are much more keyed into her mental state. As with L’Avventura, the exterior landscapes and sites become reflective of the soul.

But this is a talkier film than Antonioni’s and I was struck by how harshly the Joyces speak to each other, with only Alex flashing a little acerbic wit. It doesn’t surprise me to learn that Voyage to Italy was not successful commercially, and it’s interesting to think about how the rancor between these characters must have figured into public perception of Bergman, which had dimmed after she left Hollywood (and her husband) for Rossellini and Italy. That strain textures the film from the very beginning, when the Joyces are alone together for the first time in their eight-year marriage and they’re not getting along. They talk about feeling like strangers to each other, which seems remarkable to me because they do not have any children. Couples sometimes grow apart when their energies are focused on a child, but why in the world should the Joyces not have spent time alone? Is Alex really that committed to work?

What do you make of the child issue, too, Keith? That becomes a looming thought for Katherine as the film goes on and she gets a glimpse of all these Neapolitan couples and mothers outside her car window. “How beautiful the children are,” she remarks before responding bitterly to the question of what Alex thinks of kids. (“One never knows what he’s thinking.”) It’s an old-fashioned mode of thinking perhaps, but the Joyces’ childlessness points to the barrenness of their romance, which barely has even basic niceties, let alone any shows of affection. What passion does seem to exist between them, however, is jealousy and temptation, at least on Alex’s part. He’s rattled by his wife’s account of Charles, who’s like this unseen third character who threatens their relationship.

A lot of the most significant action in Journey to Italy are the scenes the couple have separate from each other, from Katherine’s sightseeing tours to Alex’s trip to Capri. What did you think of those scenes, Keith, and what they say about these characters? Rossellini crosscuts so meaningfully between them, no?

Keith: The childlessness is another point of contrast between the world the Joyces know—business oriented, cold, repressed—and the world into which they’re voyaging. I don’t necessarily think the film is judging the Joyces for not having kids (though it’s easy to read it that way) so much as using children to provide another point of contrast. They come from barren, sexless England! This is fertile, hotblooded Italy! These are, of course, stereotypes, but Rossellini knows this and, as an Italian, he’s allowed to indulge them, right? (Just as a side note: Bergman’s Swedishness complicates this a little, but Sweden, too, is a cooler sort of place than Italy.)

There’s another literary connection, too. In Victorian novels, childlessness was always code for a marriage being sexless and often the husband being impotent. I don’t think the latter is the case with Alex, who seems much too interested in other women, and too disappointed when his flirtation in Capri fizzles out. But something has clearly squelched whatever passion existed between our central couple. It seems like a marriage that can’t be saved, that passed its expiration date well before the events of the film.

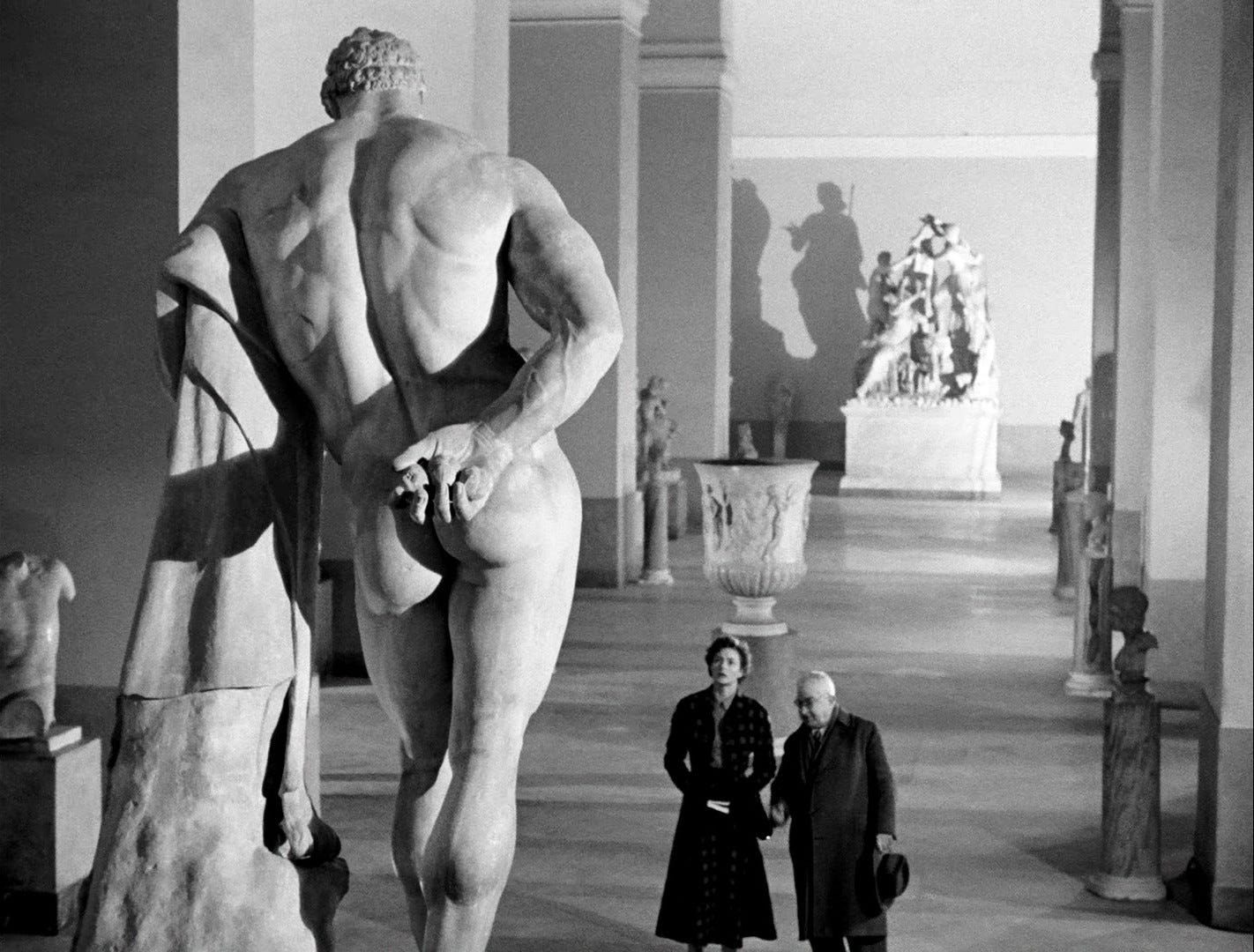

Yet the ending hinges on us believing in its miraculous rekindling. And, maybe you disagree, but I found that scene, and the Pompeii scenes leading up to it, overwhelmingly effective. Rossellini’s choice to place his characters on separate journeys that converge has a lot to do with why this moment works. Each has to take the decision to divorce up the brink before leaping back from it. It’s here that I think the film is a little uneven. I like Sanders’ performance and his scenes with other women, including the saddest sex worker in Naples. But Bergman’s scenes are on another level entirely. The combination of the score, the fluid camerawork, and Bergman’s performance capture the ways each stop on her tour serves as a revelation, and does so in ways only possible in movies, whatever Voyage to Italy’s debts to literary works. That starts with the visit to the Naples Museum, in which Katherine is surrounded by sensual sculptures that remind her of everything missing from her life and feelings that she fears she might be buried alongside Charles, and continues as she’s overwhelmed by a catacombs visit in which she’s surrounded by reminders of the inevitability of death.

You’re right to suggest that neither would work nearly as well without one another, however. So, let me ask you, assuming you agree with my reading of what’s going on with Katherine, what would you say is going on with Alex? And did the ending work for you? The reunion during the street festival is beautifully played, but it’s the visit to Pompeii that makes this movie unforgettable. Alex and Joyce are able to live in a moment frozen in time, where they watch as the outlines of another couple, one who lived centuries before them, form before their eyes. It plays a bit like they’re being made to confront both the howling loneliness of existence and what love means in the face of the void. Did you find that scene as powerful as I did?

Scott: The turnaround at the end is so startling, I’m still wrapping my head around it, though I’m inclined to appreciate this torrent of emotion between the Joyces after a film where they’re almost cool to each other, if not separated entirely. It actually reminded me quite a bit of the ending to another Sight & Sound entry we talked about recently, Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life, when we (and the film’s white characters) learn the full extent of a Black woman’s life after she’s gone. The Sirk film goes quite a bit further, though, in setting us up for that surprise, given its thematic focus on the racial imbalances of the central friendship between women of different races, despite the mutual affection they both share. That’s not to say that Rossellini doesn’t spend Journey to Italy setting the table for this miraculous final sequence, but I’d be lying if I said that the bond between the Joyces is strongly suggested in the lead-up to the finale.

That said, I have a couple of thoughts on it. One, the context of Katherine getting swept away in the crowd reminded me a little of the inciting incident in Force Majeure, when an avalanche triggered at a ski resort goes out of control and a father instinctually opts to save himself rather than protect his family. That’s a telling response in the moment, and the marriage unravels from there. The inverse happens here, in that Katherine is carried away in the crowd and Alex rushes to save her, which may not be the impulse we’d expect from a guy who’s stiff in all the ways you’d guess from an upper-class British workaholic. The film is asking you to take a leap of faith that, to me, is transversable mostly because Rossellini stages it with such urgency, as if circumstances have provided the defibrillator paddles necessary to jolt this relationship back to life. You want to surrender to the moment.

I’m glad you brought up Eyes Wide Shut earlier in the discussion, because that feels like such a similar dynamic, with a partnership that’s breaking apart at the beginning and (tentatively) rekindles at the end following a dream-like odyssey that the couple does not experience together. Here, both the Joyces have a “journey” in Italy, and it’s the time they spend apart that clarifies their thinking and eventually leads to a reunion, though not without jealousy and temptation first. For Katherine, her various museum and site visits are prompted by another man, Charles, and the feelings for him that she still carries with him. Alex is clearly stung by that—a sign that he actually does care, really—and it’s remarkable to see Katherine’s ecstatic response to the things she sees, especially the burbling heat and smoke of volcanic activity. As for Alex, his trip to Capri leads him to a couple of different women who draw his interest but nothing comes of either of those encounters. If you’re looking for a common denominator here, perhaps it’s the fact that Italy ignites some dormant passion within the Joyces and the climax is the point where they come alive together at the same time and in the same place. No more missed connections, like that scene where Alex comes home from Capri and Katherine is torn between greeting him and pretending to be asleep. (She chooses the latter.)

I laughed at your lines about the Joyces from “barren, sexless England” staying in “fertile, hotblooded Italy,” but Journey to Italy may be just as simple as that, right? Alex may kick off the film complaining about the noise on the road, but this is a place that would excite the senses for a couple like the Joyces, however much someone like Alex wants to see a gorgeous villa with a terrace view as a piece of real estate that he needs to unload as soon as possible. The hotbloodedness of Italy quite literally seeps through the surface at one point and it’s doing it figuratively all the time when the two are out and about. That’s a pretty stark difference between this and a film like L’Avventura, which is full of landscapes and structures that feel spiritually vacant. In Journey to Italy, the country is alive with so much activity that it shakes the Joyces out of their complacency. It seems, in the end, that they have the same chance of getting divorced as they do to reaffirm their love for one another. The film calls them into action.

Any final thoughts on this one, Keith? And what do we have coming up?

Keith: Final thoughts: Not really beyond wanting to go to Naples. As for what’s next, we’ve got another logjam in the #67 spot, which is home to everything from a towering silent classic to the shortest film on this list. Since this one was new to you, how about we do one I haven’t seen before: Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev.

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

If this discussion piqued your curiosity you should know that a) This movie is on the Criterion Channel and b) it's quite short. Take 90 minutes to check it off your list.

I just caught up with this one a couple nights ago so I could read this. The turnaround at the end was a bit jarring for me but that comment from Scott about how their marriage now has about equal chances of success or failure and this is a call to action really helped sort it in my mind.

I also appreciated both Keith's note about its length (I've been sorting the S&S movies I haven't seen by length so I know when I can fit one in) and the comparisons to Eyes Wide Shut, which I haven't seen but am planning on watching as part of my personal "Hey 1999 was 25 years ago!" project I've been conducting.

See you at the next one!