#67 (tie): ‘Metropolis’’: The Reveal discusses all 100 of Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time

Fritz Lang's towering sci-fi landmark depicts a future filled with towering spires, robots, and political unrest.

On December 1st, 2022, Sight & Sound magazine published “The Greatest Films of All Time,” a poll that’s been updated every 10 years since Bicycle Thieves topped the list in 1952. It is the closest thing movies have to a canon, with each edition reflecting the evolving taste of critics and changes in the culture at large. It’s also a nice checklist of essential cinema. Over the course of many weeks, months, and (likely) years, we’re running through the ranked list in reverse order and digging into the films as deep as we can. We hope you will take this journey with us.

Metropolis (1927)

Dir. Fritz Lang

Ranking: #67 (tie)

Previous rankings: #37 (2012), #32 (2002).

Premise: In a magnificent city of the future, a stark class divide persists between the wealthy city planners who live atop grand skyscrapers and the penniless workers who toil in the catacombs below, maintaining the machines that keep this industrialized Utopia humming along. But a generational divide opens up between the city’s cold-hearted mastermind Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel) and his son Freder (Gustav Frölich), who is so moved by the bewitching Maria (Brigitte Helm), an advocate and prophet for the less fortunate, that he visits the underworld and is shocked by what he witnesses. The tension between father and son—to say nothing of the mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), who has his own agenda—threatens to explode in a rebellion that could raze Metropolis to the ground. That is, unless the hand of the workers and the head of the founders can be reconciled by the heart of a mediator.

Scott: Can I confess something right off the top here, Keith? I think several of the criticisms that greeted Fritz Lang’s Metropolis when it was released in 1927 are reasonable. The film is too long. The plotting is confusing and as politically naive as the young, slow-witted Freder at the beginning of the story. And I’m unconvinced by the central idea of the Hand (the workers, represented by a burly foreman named Grot) and the Head (the rich and brainy executive class, represented by Joh Fredersen) needing a mediator, the Heart (represented by Freder), to bring them together. That doesn’t seem to me how revolutions of this kind work, or even agreements between workers and management like union contracts, which result from negotiation rather than kinship. When you have a situation where workers are reduced to automatons in underground steam pits, no different than the machines they operate, and unrest starts to spread into mob rebellion, I just don’t see that ending in a handshake. And I don’t see how a man like Joh Fredersen, who’s shown coldly banishing his long-time assistant as if sending back lunch, can get to a place where he’s willing to compromise and presumably move toward a more equitable society.

So for anyone looking for us to blow holes in a canonical classic, there you have it. And yet Metropolis is obviously the gold standard of screen science-fiction, a film so vastly influential in its production design, special effects, and eye-popping imagery that you can watch it now and see the century of cinema that Lang’s magnificent heart-machine would forge. You can perhaps also see how Metropolis would get slashed up and manipulated over the years, whether edited down from its then-immense 153-minute running time for its original American release or cherry-picked into a slim 83-minute cult experience for Giorgio Moroder’s 1984 adaptation, featuring songs that Moroder composed and recorded with pop stars like Freddie Mercury, Pat Benetar, and Adam Ant. It honestly feels strange to sit down and watch Metropolis in full, not just because that hasn’t always been possible, but also because so many of its most memorable images and sequences have been sampled or copied for popular consumption.

Let me press pause on the heresies for now, though, and praise the first section of Metropolis, which just bowls you over with the scope and artistry of its world-building. In silent cinema, only D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance has anything like its power just to knock you out with its sheer size, and you might have this image in your head of Fritz Lang as Joh Fredersen, pitilessly overseeing the laborers responsible for such a production. (The stories of Lang’s perfectionism, which extended to brazen endangerment of the cast, including hundreds of poor children wading in freezing water, are pretty startling.) Yet the succession of immediately arresting sequences that open the film is virtually unrivaled: A new Industrial Age defined by gears and wheels and clocks that Lang pieces together in superimposed collages; a shift change where one faceless group of worker drones, all in the same uniform, shuffle out of one side of a caged tunnel as another shuffles in; a “Son’s Club” high in the clouds where wealthy, athletic young men compete on the track and painted women are gathered in the “Eternal Gardens”as leisure companions.

In the year 2024, when we’re having to grapple with so many franchises and write a lot about world-building—I’m recapping Dune: Prophecy for Vulture, and woof do you feel the heavy-lifting on that one—I feel particularly appreciative of how boldly and efficiently Lang establishes this Utopia powered by an underworld underclass that’s far from utopic. Is it simple? Sure. Can you miss the Biblical significance of Fredersen’s tower being called the Tower of Babel? You cannot. But cinema often thrives on strong, clear visions like those early foundational minutes of Metropolis, so long as the filmmaking itself has a certain graphic force. You might criticize Lang and his then-wife Thea von Harbou—who wrote the script based on her novel (which was itself reportedly written with the screen in mind)—for a near-propagandistic depiction of the class divide, but their future Industrial Age would not have been so out of line with the recent past, when unchecked labor abuse led to danger and vast inequality. The science-fiction genre gives you all the more license to put that in stark terms.

Maybe the film’s most famous sequence—one that Mike D’Angelo analyzed for us at Tthe A.V. Club for his “Scenic Routes” column—involves young Freder, inspired by his encounter with the mysterious Maria, to venture down to the catacombs to see how the other half lives and works. Among the horrors he witnesses is a massive machine where workmen are engaged in a repetitive labor that turns them into mere cogs. Except they’re not cogs, in that keeping up these movements on this stream-spewing platform is exhausting and overwhelming, and failing to keep up means the machine itself will overheat and explode. As Freder watches this industrial accident as it happens, he hallucinates a nightmare where the machine is the mouth of Moloch opening up as men in bondage are thrown into its maw. Surely Charlie Chaplin, who’d do a more comic version of this assembly-line drudgery in Modern Times a decade later, was watching.

So I’m curious, Keith: How does the film play for you overall? We can talk about how vastly influential Metropolis has been on science fiction and its status as a masterpiece of German expressionism, but I wonder if you have any reservations. Am I sweating the wrong stuff here? Do you find the entirety of the film as persuasive as, say, the first third?

Keith: I think the slick move here would be to say, “Scott, what are you talking about? How dare you find flaw with an obvious masterpiece?” I do think Metropolis is a masterpiece, but “mastperience” doesn’t mean “perfect,” and here’s it’s a case of what makes the film great overshadowing its problems, and then some. But your reservations are my reservations, particularly when it comes to the film’s simplistic politics. I think the class divide is set up brilliantly, but I kind of roll my eyes at the head / hands / heart metaphor. On top of everything else, it takes the divide between the underclass and the overclass as a given that’s not going away, maybe even the natural order. The final scene essentially feels like the future will look a lot like the past, just nicer. It’s probably worth noting that whatever Von Harbou’s politics were at the time and however much Metropolis owes to Marx, she’d soon be a Nazi loyalist. (Lang, whose mother was a Jewish convert, fled the country after being offered a chance to head UFA by Joseph Goebbels.)

That said, the scale and ambition of the movie, and Lang’s success at fulfilling that ambition, makes my jaw drop every time I watch Metropolis. The same simplicity that makes Metropolis clunky as a political statement is an asset in other ways. The factory where the workers labor looks truly hellish even before Moloch makes his appearance. The world atop its skyscrapers feels genuinely Olympian. It’s set in a future that reflects the present while evoking the mythic and the eternal.

As for its influence, it’s hard to understate, isn’t it? It’s the city of the future that informs every city of the future, but I think it’s just as notable that the film depicts not just the gleaming skyscrapers and gargantuan industrial institutions, but also the places where the citizens of Metropolis live. It’s not spectacular explosions that threaten the city in the climax but floods and riots. It feels like a fully functional (if in many ways dispiriting) urban environment. Then there’s the projection of Art Deco design into the years to come. All visions of the future are rooted in the present and Metropolis takes all of Art Deco’s chrome and curves and decorative touches to their extreme, but maybe not their limit. The Chrysler Building, for instance, wouldn’t look out of place in its skyline.

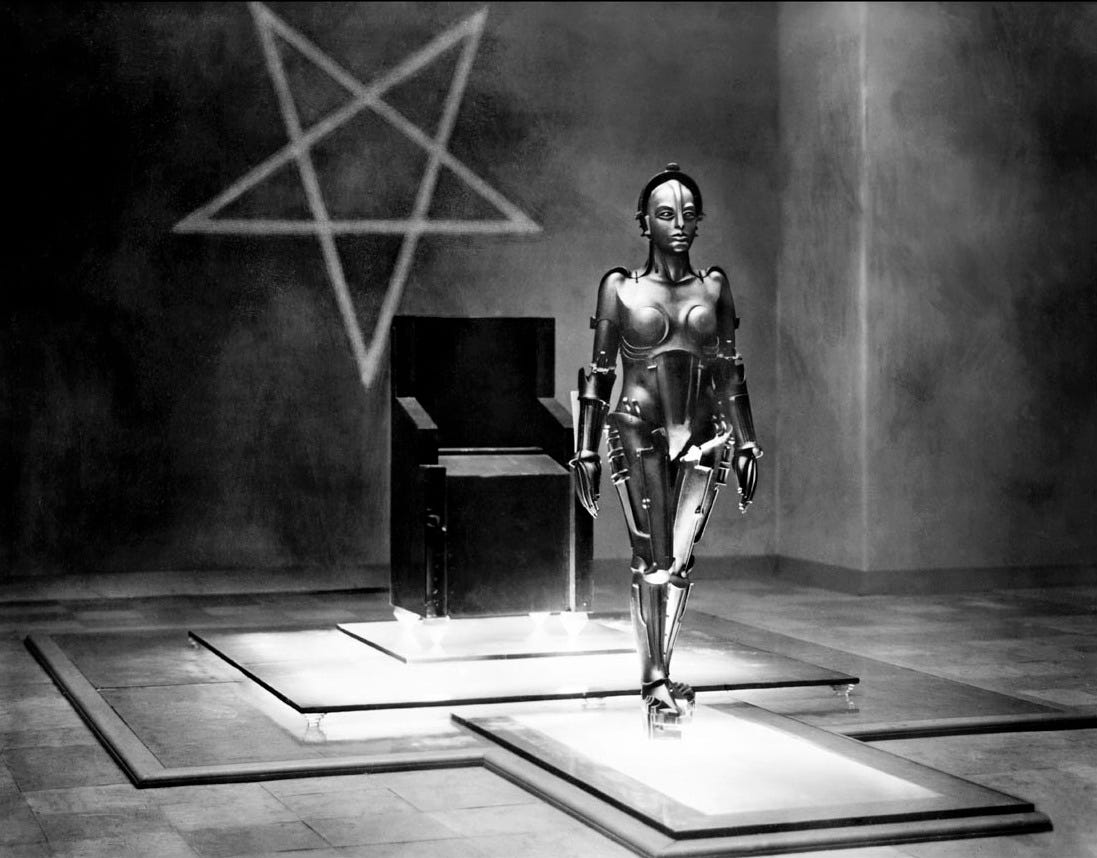

To focus on one detail, the influence of the film’s maschinenmensch is everywhere. It’s a precursor of every robot that followed that aspired to be more than a boxy machine (or a gorilla costume with a diving helmet placed atop it). George Lucas famously asked Ralph McQuarrie to draw from it when designing C-3PO (which is even more evident in McQuarrie’s original concept art). But you can see it everywhere from Westworld (original or HBO) to Ex Machina to Austin Powers’ fembots (and all the past robots they draw from). Just as influential, however, are the questions raised by the maschinenmensch’s ability to pass for human. Metropolis might not have been the origin of the philosophical issues raised by a machine perfectly emulating humanity—and the maschinenmensch never feels particularly machine-like once it takes on Maria’s form and turns evil—but it certainly made a major contribution.

Scott, where do you most distinctly see the film’s influence? And we should maybe look beyond sci-fi. The model used for the final act of the movie—in which world-threatening catastrophes erupt on several fronts at once—seems like the model for the action blockbusters that followed. And what do you think of the performances? I agree that Joh Fredersen’s arc isn’t really convincing, but Alfred Abel’s performance almost sells it. And Brigitte Helm is pretty magnetic both as Maria and her doppelganger, characters who fully commit to improving the world and tearing it down, respectively.

Scott: Metropolis joins several movies on the Sight & Sound list where it’s influence is so obviously pervasive that you almost feel a sense of déjà vu while watching it. Keith, have you heard of a little movie called Blade Runner? That’s the one that gets cited the most and you can really see it whenever Lang offers matte-painting-enhanced exteriors where trains and flying machines are moving high up off the ground, unbound by the gravity that continues to bind most of us (and our transportation) to the filthy old ground. In fact, it’s kind of funny to me that no one seems to occupy the actual surface of the planet: The ultra-wealthy live atop high rises and the workers toil in the catacombs like ants. The middle class has been wiped out, metaphorically speaking. You can also see a lot of Metropolis in the byzantine, bureaucratic purgatory of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, which may have much more interest in how ordinary apartment-dwellers live, but shares with Lang’s film an imposing urban coldness. These are movies where the city’s visionary designers had an aesthetic utopia in mind, but wound up building a place where actual humans would struggle to live. (And I’m not sure if Metropolis had anything to do with Miami’s Art Deco boom in the ‘20s and ‘30—it was a style that was apparently sweeping Europe at the time—but if you’ve ever been to South Beach, it’s Metropolis in pastels.)

As for the performances, they’re not easy for me to judge, since the acting in silent movies is much different than sound and the acting in German silent movies is much different than other silent movies. (If you’ve ever seen Emil Jannings in a movie, you’ll know exactly how he’s feeling at any given moment.) That said, I’m glad you singled out Alfred Abel as Joh Fredersen. His arc may not be convincing because I don’t think enough time to spent tracking it, but Abel is notably low-key in how his Fredersen is able to coldly dismiss his long-time assistant Josaphat, whose severance is basically a one-way trip to the catacombs, and feel truly stung by his son’s apostasy. In order for the hand/head/heart alliance to come together in the end, it’s Fredersen who must be the most capable of change, in part because he loves his son and in part because he can see that this magnificent city he’s designed isn’t operating justly. Helm’s dual roles as Maria and robot-Maria is a more celebrated performance, though you’re right that she isn’t as suggestive of artificial intelligence, which may be necessary for the shock/relief of her robot doppelganger revealing itself when she’s burned at the stake. But the human Maria is the truest catalyst of the film, and Helm can convincingly ignite Freder’s conscience with a look.

One of the things I like about watching silent movies by great directors like Lang, too, is that you can see cinematic techniques we take for granted being deployed and advanced in a film like Metropolis. The precision of Lang’s superimpositions of factory gears and levers toward the beginning is one example, along with various in-camera effects that operate like a magician’s trick. Then you get the sophisticated cross-cutting between the two Marias in peril at the same time, as the angry mob chases down the maschinenmensch in one extended sequence while the mad Rotwang chases the real Maria to the top of a cathedral, where she dangles precariously on the rope of an enormous bell. We would know from a later film like Lang’s M how he feels about mob violence, even against perpetrators we might fairly consider “evil,” and so here the two Marias are unified in their terror. The shot of the maschinenmensch laughing maniacally on the stake recalls another Metropolis-influence movie: The very end of Inglourious Basterds, where Mélanie Laurent’s Shoshanna cackles in projection as she successfully torches the Nazis.

Speaking of Nazis—please, we mustn’t pause here to admire that segue—the history behind Lang and Thea von Harbou’s collaboration, marriage, divorce, and contrasting political destinies is fascinatingly thorny. While she did indeed make films for the Nazis during the war, von Harbou also strongly rejected the criminalization of abortion in 1931 and secretly took up with an Indian journalist after her divorce from Lang, which was forbidden by the regime. She would later claim that she joined the Nazis to protect Indian immigrants in the country, though that strains credulity a bit. Still, the attraction that the Nazis felt toward Metropolis—Goebbels saw it as a model of what he wanted German cinema to be—is a little hard for me to grasp, since the film is so wrapped up in class inequalities. I suppose the ending might suggest a starting point for fascist ideals: A glorious city that’s not torn apart by revolution, but brought together in a unification of the social classes. You could see the city becoming more powerful and living up to its utopian ideals, rather than being a fractured place that needed to be razed.

What about you, Keith? Any theories about the film’s politics? I’m also curious to know if you’ve seen the Giorgio Morodor version of Metropolis, which was lambasted at the time but sounds like an intriguing pop experiment at the very least. There are so many different cuts of Metropolis out there and so many scores, too, but you can have a lot of different experiences with this particular work and the right (or wrong) music could greatly affect how you respond to it.

Keith: I do think we see one person who lives at ground level: Rotwang. Is that symbolically significant? I don’t know, honestly. As for the film’s politics, to me I think they boil down to “Let’s all get along.” The laborers should continue to labor, just under better conditions. The ruling class will continue to rule, but be nicer about it. The film begins with this magnificent depiction of the divide between Metropolis’s heights and depths, then winds its way to a noble but wishy-washy final statement that will likely go down better with conservatives who don’t want any fundamental changes. Revolutionary it’s not.

I have seen the Moroder cut, which is obviously not for purists, though it’s worth noting that Moroder’s version, despite being much shorter than 153 minute running time of the original release, was for a time the most complete version in circulation and the first attempt to restore the film. It’s fundamentally silly. Let’s make Metropolis friendly to MTV kids! You know what would improve Lang’s vision of a futuristic dystopia? The music of Bonnie Tyler, Billy Squier, and Loverboy! But it also plays like an earnest act of admiration, and if you like Moroder’s music, the score is pretty cool. I’m glad it exists, honestly. It’s kind of fun and it’s not like it erases the full, proper version of Metropolis.

The best experience is almost certainly the restored version put out by Kino, which I was lucky enough to see projected a few years back. (Kino also brought the Moroder version back into circulation.) The many different cuts vary wildly in quality. But there are certainly options. For scheduling reasons, I had to watch part of this movie in a coffee shop and found a version streaming on a free service that looked good but had a score I didn’t like. So I muted it and played it to Philip Glass’s Symphony No. 4, the one where he incorporates themes from David Bowie’s Heroes. It worked really well! Maybe it’s the connection between two works made in Berlin at two different points in German history. (If it works just as well with Dark Side of the Moon, I don’t know and will leave it to others to determine.)

Scott, any albums you’d play as an alternative score? And any last thoughts before we press on?

Scott: I should have consulted you about score recommendations first, Keith, because I didn’t have any alternatives in mind. I haven’t seen the Moroder version, but the type of music he made certainly sounds like an appealing match with Metropolis, though tracks by Bonnie Tyler and Loverboy do not. Given the film’s prominence and importance, as well as its eternal cult appeal, you’d think we might have some artists step up and tailor a score to it, though maybe the running time and the public-domain factors are discouraging. Philip Glass does sound like a fine solution, because you do need the right ambient wallpaper behind a movie like this. If I’m wishcasting, I’d like to see Mica Levi, the composer of Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin and The Zone of Interest, as well as Pablo Larraín’s Jackie, give it a shot. Or maybe Stereolab.

Not too many final thoughts from me, other than a mild regret that my misgivings about the film’s plotting and politics may have suggested that I don’t feel like Metropolis deserves a place on the Sight & Sound list. While I’m excited to talk about a Fritz Lang film I like even more up at #36 (M)—see ya in a year-and-a-half or so on that one, Keith—the world-building and image-making in Metropolis makes it one of the great achievements of the silent era, and a true touchstone of screen science-fiction. My heart is telling my head to make my hand type these things. So rare for my broken body to operate this harmoniously.

Any last thoughts from you, Keith? And what’s next?

Keith: Just beware of metal women no matter how alluring they might look, I guess. They tend to have agendas. As for what’s next, we’ve got one more film tied for the #67 slot: Chris Marker’s short, singular, La Jetée

Previously:

#95 (tie): Get Out

#95 (tie): The General

#95 (tie): Black Girl

#95 (tie): Tropical Malady

#95 (tie): Once Upon a Time in the West

#95 (tie): A Man Escaped

#90 (tie): Yi Yi

#90 (tie): Ugetsu

#90 (tie): The Earrings of Madame De…

#90 (tie): Parasite

#90 (tie): The Leopard

#88 (tie): The Shining

#88 (tie): Chungking Express

#85 (tie): Pierrot le Fou

#85 (tie): Blue Velvet

#85 (tie): The Spirit of the Beehive

#78 (tie): Histoire(s) du Cinéma

#78 (tie): A Matter of Life and Death

#78 (tie): Celine and Julie Go Boating

#78 (tie): Modern Times

#78 (tie): A Brighter Summer Day

#78 (tie): Sunset Boulevard

#78 (tie): Sátántangó

#75 (tie): Imitation of Life

#75 (tie): Spirited Away

#75 (tie): Sansho the Bailiff

#72 (tie): L’Avventura

#72 (tie): My Neighbor Totoro

#72 (tie): Journey to Italy

#67 (tie): Andrei Rublev

#67 (tie): The Gleaners and I

#67 (tie): The Red Shoes

Metropolis is one of those films that I heard about all my life and had it built up in my head and then when I finally got to watch the Kino restoration.... completely lived up to expectations.

I know I'm simply speaking from ignorance here, but it seems crazy that we were able to put images like 'Metropolis' on screen while still being completely unable to create even rudimentary synced audio.

That seems like a more tractable problem than what Lang had to do visually!