The ‘80s in 40: ‘Fast Times at Ridgemont High’ (August 13, 1982)

Amy Heckerling's ensemble coming-of-age comedy offered a slice of teen life without trimming the rough edges.

The ‘80s in 40 revisits the decade of the 1980s choosing four movies a year, one from each quarter. This entry covers the third quarter of 1982.

It’s August 1982. Do your parents know where you are? If they searched the dugout of an abandoned baseball field, would they find you there, with an older man, putting on airs of experience you soon would not need to fake? If they drove the streets, would they see you contemplating the emptiness of a future that once looked so promising while wearing a cheap pirate costume? Or somewhere at the mall? Or falling out of a van trailed by smoke? Maybe you’d be listening to the Go-Gos or Jackson Browne or “Kashmir.” Maybe you’d be alone. Maybe you’d be with someone you wanted to love you. If they saw you, out in the world living a life in which they now play only a small part, would they recognize you? Would you recognize yourself?

Fast Times at Ridgemont High appeared at the tail end of a summer defined by landmark genre films like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Blade Runner, and The Road Warrior (the list goes on and on). It’s tempting to suggest Fast Times stretched that trend into the season’s waning months. On the surface, at least, the film looks like part of the wave of raunchy teen comedies that followed in the wake of Porky’s success, but that wave wouldn’t really arrive until 1983.* Just as M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable now plays like a commentary on superhero movies accidentally made a decade or two too soon, Fast Times feels at times like a smarter, more empathetic response to the dumber movies to come.

Directed by Amy Heckerling and scripted by Cameron Crowe, the film adapts Crowe’s 1981 book of the same name, a nonfiction account of time Crowe spent undercover as a San Diego high schooler in 1979 as a still-babyfaced 22-year-old. (Though long out of print—and now quite expensive on the second-hand market—the book can be found at the Internet Archive and elsewhere.) That so much of the Crowe’s script is taken directly from its pages, if in more streamlined, movie-friendly form, might be the most surprising thing about reading the book after seeing the movie. But despite its basis in fact, there’s no mistaking Heckerling’s film for a docudrama. That it works as a teen comedy first is part of what makes it so successful, easing viewers into deeper waters than they might have expected.

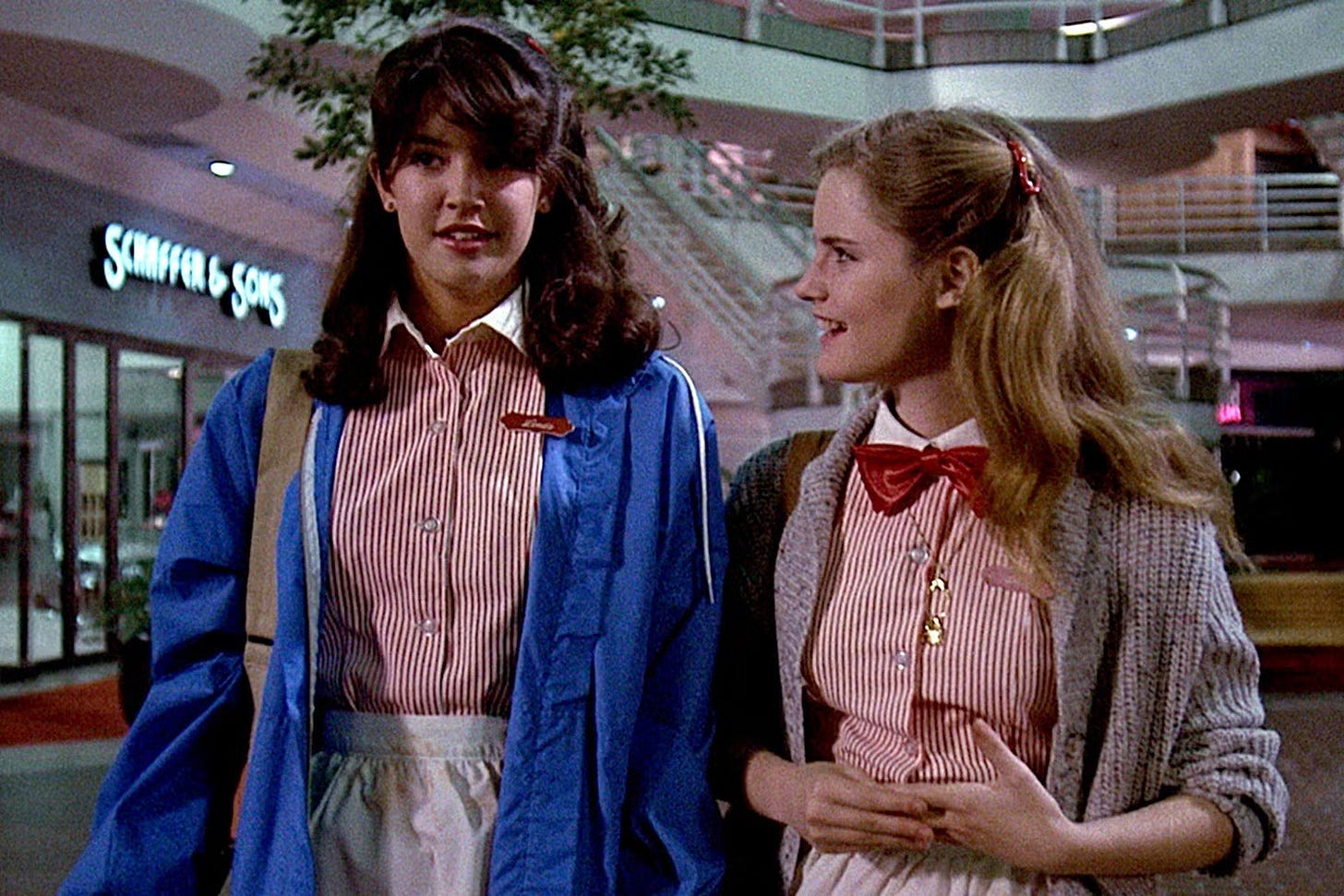

That starts with the opening credits, which introduces the film’s main characters between slice-of-life-early-‘80s life shots and sight gags at the Sherman Oaks Galleria, all set to “We Got the Beat” by the Go-Go’s. It’s joyous in the moment but a little eerie in retrospect, setting up a world in which grown-ups have receded deep into the background and teenagers have already started to define themselves not by who they are but by what they do for a living: scalper, movie usher, waitress, fast-food manager, etc. Only Jeff Spicoli (Sean Penn), a stoner, frequent surfer, and occasional student, and his coterie (played by Anthony Edwards and Eric Stoltz) seem removed from that social order, a kind of yang to the yin of Brad Hamilton (Judge Reinhold). Having defined himself by his professional success at All-American Burger, Brad spends the year watching his identity unravel after losing his job. Though the “fast times” of the title most obviously refers to some of the other rites of passage the film depicts, Brad proves there are other ways to grow up too fast. (That Reinhold was 24 when he made Fast Times, and looks like it, ends up working in the film’s favor.)

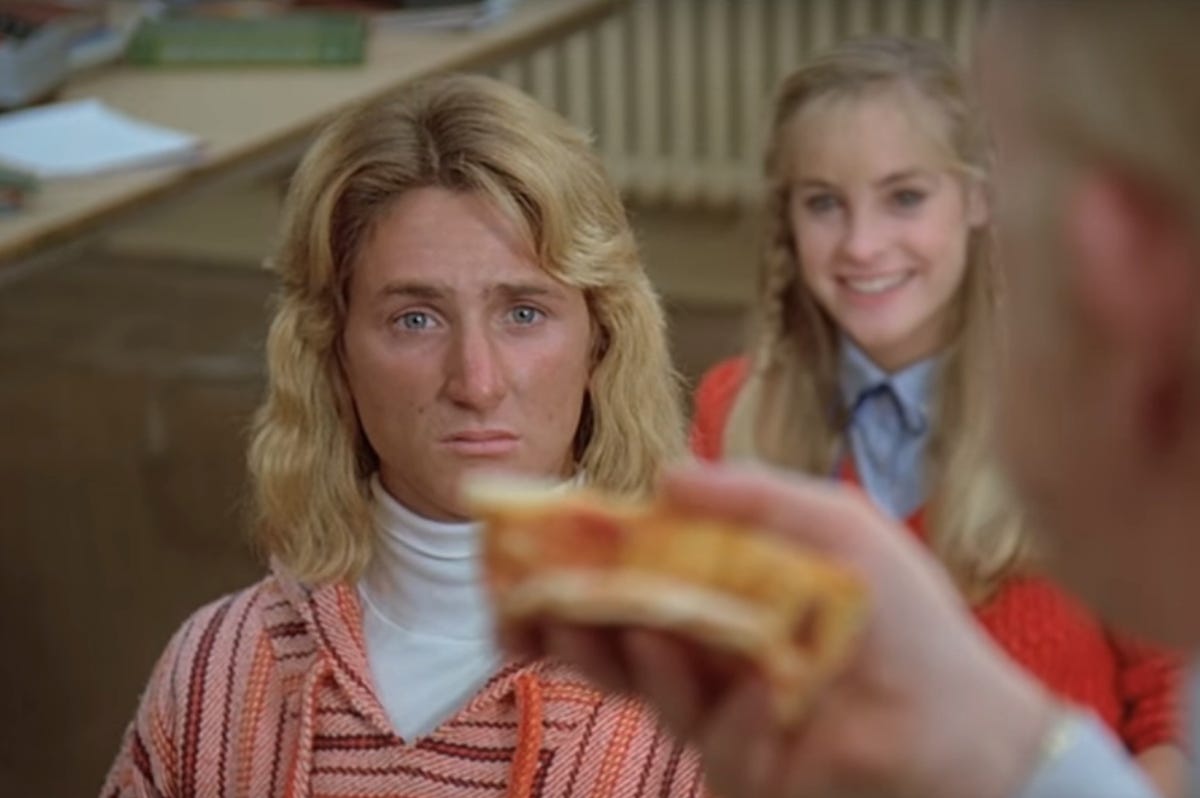

Spicoli’s clashes with Mr. Hand (Ray Walston), a history teacher whose demand that his students arrive in class on time (and not order pizza mid-lesson) proves too high a bar to clear, provide the film’s comic highlights. Phoebe Cates’ Linda plays a similar role, in some respects, on the girls’ side of the unusually balanced ensemble. Her lust-inspiring pool bikini scene gives the film one of its signature moments but, as good as Cates is, Linda never emerges as a three-dimensional character. She’s mostly there to be a nonchalant font of sexual wisdom for Stacy. That her experience seems to be with a never-seen fiancé in another city could be one of the slyest gags. Is she just making it up? But it’s the film’s depictions of the more down-to-earth characters, the ones that offered big-screen reflections of the actual experience of ’80 teendom, that define it. Brad’s unraveling, his sister Stacy’s (Jennifer Jason Leigh) entry into the world of sex, and shy Mark “Rat” Ratner’s (Brian Backer) attempt to find love give the film its shape.

Writing of Stacy’s storyline—which includes posing as an adult to date a twentysomething stereo salesman and an accidental pregnancy and abortion after pairing off with Mike’s ticket-hustling best friend Mike Damone (Robert Romanus)—Slate’s Dana Stevens praised the film’s ability to depict it “without judgment or preconception or the least hint of sentimentalization.” That description could easily be extended to the rest of the film. Like the films Crowe would go on to direct, Fast Times buzzes with empathy for its characters, even when they make stupid mistakes. Maybe especially when they make stupid mistakes.

Fast Times at Ridgemont has become such a cultural institution, it’s almost easy to take for granted its cleareyed evenhandedness, a combination of Crowe’s script, Heckerling’s sharp direction, and performances from soon-to-be stars in parts both large and small. It’s not that the film told it like it is. It’s that it gets at the awkward truths of growing up by way of a comedy that could draw in the teens of 1982 and live on in perpetuity via cable** and home video. A few years later, John Hughes would earn praise for making films that spoke to teens in a language they recognized as their own, but even in Hughes’ best films, it’s easy to feel the effort and the urge to impart adult wisdom. Fast Times offers a vision of kids trying to navigate a world into which they’ve seemingly been dropped with little guidance, one they have to figure out one mistake at a time.

Not that everyone, particularly the adult everyones, saw it at the time. Roger Ebert famously panned the film, asking “How could they do this to Jennifer Jason Leigh?” But Ebert wasn’t alone in not embracing Fast Times. In the Baltimore Evening Sun, Stephen Hunter puzzlingly wrote, “It isn’t even anthropology (because it has no insights).” Yet Hunter came this close to getting it by calling it “true to life in another respect —or at least true to memory (or at least true to a memory, my own)—in that it depicts everybody as being generally miserable.”

In Crowe’s book, Stacy’s mother wakes her by telling her “These are the best years of your life!,” echoing a message conveyed not just by parents but by, well, just about every other aspect of a culture that can’t imagine anything more fun and valuable than being young, and suggests that if these don’t feel like the best of your lives, you’re doing something wrong. Nestled between the stoner jokes and masturbation gags, Fast Times at Ridgemont High offered welcome reassurance that, no, you weren’t, that you weren’t doing anything that others weren't doing, that this was how it was for everybody and maybe always would be and that was okay.

Also:

It’s one of those quirks of history that in August 1982 Fast Times looked like part of a triptych of films offering visions of the State of the Teen Nation. Those in search of a whiplash-inducing triple feature could (and still can) watch the film back-to-back with Class of 1984 and The Last American Virgin. The former is, at heart, a nastier-than-most Death Wish-inspired revenge movie in which an idealistic high school music teacher (Perry King) is pushed too far, dammit. Directed by Mark Lester (Commando, Firestarter) from a script co-written by Fright Night and Child’s Play’s Tom Holland, it’s well done of its type, which is to say it’s mostly repellent but undeniably effective. It also offers great examples of the generic “violent punk” type that existed only in ‘80s movies and some memorable turns from Roddy McDowell (as a terrified teacher) and Michael J. Fox.

More interesting (and more bizarre) is The Last American Virgin, a Golan-Globus-produced remake of the Israeli hit coming-of-age film Lemon Popsicle (which also inspired a series of sequels). But where the original was set in early ‘60s Tel Aviv, Virgin takes place in then-contemporary Los Angeles and plays at times like a darker mirror of Fast Times told from the much narrower perspective of its horny teen boy protagonists. It’s not nearly as good as Fast Times, but it’s similarly frank about abortion (if far more exploitative in depicting it) and builds to the single most depressing sequence in any ‘80s teen movie, one so stunningly bleak it’s best left unspoiled.*** Both films are now footnotes, but sometimes it’s the footnotes where you’ll find fascinating details that shouldn't be skipped.

Speaking of footnotes, Fast Times at Ridgemont inspired a couple of direct companion pieces. In 1986, CBS aired seven episodes of Fast Times, which adapted the film into a half-hour sitcom. The characters remain the same and the style is far more cinematic than most network comedies. (Heckerling directed three episodes, joined by Neal Israel and Claudia Weill, among others.) Walston and Vincent Schiavelli even reprise their roles as teachers with some familiar faces like Courtney Thorne-Smith and Patrick Demspey as, respectively, Stacy and Damone. (Fear’s Lee Ving even shows up in the pilot as one of those violent ‘80s punks Class of 1984 warned us about.) But it plays like, well, the watered-down TV version of Fast Times at Ridgemont High, particularly whenever Dean Cameron is on screen as a much tamer Spicoli.

Finally, Fast Times debuted two years after another attempt to draft off Fast Times at Ridgemont High’s success. “From the creators of Fast Times at Ridgemont High comes something even faster,” the trailers and TV spots for The Wild Life boasted. The Cameron Crowe script provides the main connection in this ensemble comedy set in the Los Angeles suburbs, but only one character, a Vietnam-obsessed teen named Jim (Ilan Mitchell-Smith) who idolizes a troubled vet named Charlie (Randy Quaid), has any of the original’s authenticity. Otherwise, it’s mostly notable for an Eddie Van Halen score (recycled in part for later VH albums) another memorable cast (Lea Thompson; Eric Stoltz, given more to do here than in Fast Times at Ridgemont High; Chris Penn, subbing in for his brother as the comic relief; Robert Ridgeley as a sleazy landlord; Russ Meyer veteran Kitten Natividad as, unsurprisingly, an exotic dancer) and a much-repeated catchphrase that never took root: “It’s casual.” But it’s never too late. Try it out on your friends and family tonight!

Previously:

Poltergeist (June 1982)

Porky’s (March 1982)

Body Heat (August 1981)

Stripes (June 1981)

Heaven's Gate (April 1981)

Cutter’s Way (March 1981)

9 to 5 (December 1980)

Ordinary People (September 1980)

Urban Cowboy (June 1980)

Little Darlings (March 1980)

* The year of Joysticks, My Tutor, Spring Break, Screwballs, Losin’ It, Porky’s II: The Next Day, Private School, and more, undoubtedly.

** The basic cable cut of the film, available on the Criterion Collection edition, makes for fascinating viewing, substituting deleted scenes and alternate shots to take the place of material that could not be broadcast.

*** I’d also argue that it does feature a better (or at least hipper) soundtrack than Fast Times at Ridgemont High, which, true to life, contains a lot of stars from the previous era still hanging around next to emerging new wave stars. But it’s the new that dominates Virgin, which includes songs from Devo, The Police, Phil Seymour, U2, Blondie, The Human League, The Plimsouls, and, overlapping with Fast Times, The Cars and Oingo Boingo and makes heartbreaking use of James Ingram’s “Just Once.”

So I saw Last American Virgin whenever it hit HBO (we didn’t have cable, but my grandparents did, so I binged HBO whenever I was there), was probably 10. I still remember the gut punch. To this day, the song Just Once makes me want to tear up; I remember watching the credits begin and feeling as lost and blindsided as the main character. Thinking about it as an adult, that was a really bold move for the filmmakers and studio.

It's a very episodic movie, which I held against it upon first viewing. I did the same for Dazed and Confused. Both are movies that benefit from repeated viewings, where you get to hang out with the characters rather than look for a plot.