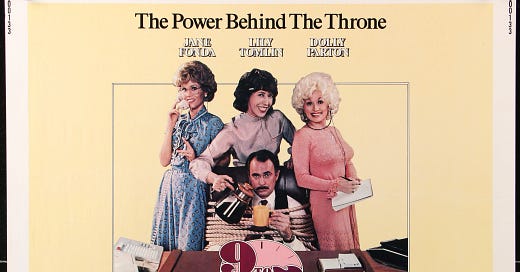

The ’80s in 40: '9 to 5' (December 19, 1980)

At the end of 1980 Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton starred in an unabashedly feminist, pro-labor comedy so fun even Ronald Reagan liked it, mostly

The ‘80s in 40 revisits the decade of the 1980s choosing four movies a year, one from each quarter. The entry brings us to the end of 1980.

When did the 1980s begin? When does any decade really begin? The turnover doesn’t always sync up with the calendar. None of the three 1980-released movies previously covered in this column — Little Darlings, Urban Cowboy, and Ordinary People — feel deeply invested in the concerns of the decade as we’ve come to think of it. They’re about wayward post-hippie kids, sensitive men, and a cultural identity and lifestyle that peaked alongside the film exploring it. It’s convenient to think of films as being revealing of their time, but when it comes to release dates it’s best to take some lag into consideration.

For the purposes of this column, let’s say that the 1980s began on February 14, 1981. That’s when, while taking a break at Camp David, recently inaugurated President Ronald Reagan and his wife watched 9 to 5, a comedy first released in December of the previous year. “Ran a movie,” Reagan wrote in his Presidential Diary. “It was a comedy (Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton & Lilli [sic.] Tomlin) ‘Nine To Five.’ Funny—but one scene made me mad. A truly funny scene if the 3 gals had played getting drunk but no they had to get stoned on pot. It was an endorsement of Pot smoking for any young person who sees the picture.”

It’s tempting, and not entirely wrong, to read this as a fogeyish response to the three heroines getting high and fantasizing about killing their boss Franklin Hart Jr. (Dabney Coleman). But it’s not entirely right to dismiss it, either, because Reagan was kind of onto something. The film’s marijuana use is almost shockingly casual, even in the post-legalization 2020s. Tomlin’s character — Violet, a widow raising four kids on her own — supplies a joint given to her by her teenage son (she puts up token resistance but ultimately takes it and doesn’t do anything to punish him). Her kid gets high. She gets high. So, with only the slightest push, do Judy (Fonda), a timid recent divorcée, and Doralee (Parton), a country gal secretary determined not to be consumed by big city life and predators like Hart.

No one classifies 9 to 5 as a stoner comedy, and with good reason. Only one scene, however central, involves getting stoned. But the movie also just treats pot as part of the fabric of everyday life, circa 1980, a practice not the least bit out of place in a PG-rated movie. It was a vision of America Reagan didn’t like, both, it’s easy to surmise, because he objected to drug use in any form, and because of the broader implications of such moments being depicted without judgement in a hit comedy with beloved actresses. The country he knew was slipping away. The counterculture had seeped into the culture at large. It was his job to drain it out again.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

Is it telling that this was Reagan’s only objection to an unabashedly pro-labor (he was mere months away from firing over 11,000 striking air traffic controllers), feminist film depicting the life of working women as a constant stream of unequal treatment, sexual harassment, professional stagnation, and aggressions too unmistakable to be called micro? Reagan ran for president in 1980 while expressing an opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment, which had stalled out after being ratified by 30 states, a position that put the party at odds with the expressed support of Richard Nixon, Dwight Eisenhower, Gerald and Betty Ford, Sandra Day O’Connor, Strom Thurmond and others. Reagan himself had flip-flopped on the issue, a move that looks motivated by political expediency. In attacking the ERA, Reagan used the absurd but by-then-common, Phyllis Schlafly-favored argument that the law could be bad for women because they might then be drafted to serve in combat roles in the military. If the other problems the amendment was meant to correct persisted, well, was that really the greater evil?

9 to 5 was explicitly conceived to showcase the urgent need for equal treatment for women, even if the ERA itself goes unmentioned in the film. Formed in 1972, the production company IPC was in the business of turning political positions into mainstream entertainment. . In 1972 Fonda and politically like minded producer Bruce Gilbert, a Berkeley dropout Fonda met when he was working at her daughter’s nursery school, created IPC—it stands for “Indochina Peace Project”—to make socially relevant movies that could play to mainstream audiences.

And they were (mostly) successful. All starring Fonda, IPC’s productions leading up to 9 to 5 were Coming Home, The China Syndrome, and Rollover. The lattermost is a largely forgotten flop, but that’s still a pretty great run, particularly for what was at heart a two-person operation. IPC had good instincts, too. 9 to 5 began as a drama scripted by Patricia Resnick (then best known as a Robert Altman collaborator, now a television producer and director), but Gilbert, influenced by Preston Sturges, suggested that it would work better as a comedy. That led to the hiring of Colin Higgins, who’d most recently served as writer and director of the hit comedy Foul Play (and who got his start scripting Harold and Maude).

The result is a shaggy comedy held together by its three charismatic stars. The film veers from farce to slapstick and back again, first as Violet and Judy figure out that Doralee isn’t Hart’s mistress (after a lot of misunderstandings) then as they chase down what they believe to be Hart’s corpse and finally as they hold Hart hostage and, in his absence, run the vaguely defined Consolidated Companies together better than he ever could. That pot-smoking scene stops the film cold for one extended fantasy sequence after another, but Fonda, Tomlin, and Parton make them charming enough that it’s hard to complain. And Coleman’s so detestable as the villain that watching the women’s stoned visions of him dying over and over again—prior to a third act that makes the character suffer humiliation and considerable bodily harm—feels not only cathartic but kind of necessary.

The message is clear, even if 9 to 5 never plays like a message movie—and, if IPC had a trademark, it was that shrewd blending of issues and entertainment. But that trademark wouldn’t last much longer. 1982 brought the company another big hit with the decidedly unpolitical On Golden Pond. That same year saw the publication of a New York Times profile in which Fonda and Gilbert discussed their future plans for topical movies and an ambitious project to work with journalists in developing pieces IPC could acquire the rights to before publication, like a Rolling Stone article on computer hackers and a project about, in Fonda’s words, the "transition in Africa from white supremacy to black supremacy.” They never came to be. Though Gilbert and Fonda would work together again, IPC’s future would be limited to a 9 to 5 spin-off sitcom and the acclaimed, Fonda-starring 1984 TV movie, The Dollmaker.

By then, Fonda was everywhere, not as an actor or producer but as the entrepreneur behind The Jane Fonda Workout, a hugely successful multimedia venture that turned her into the face of ’80s fitness culture. Is it too neat to see the success of 9 to 5 less as a breakthrough than as one of the last of a school of politically minded films that would struggle to find a place in the cinematic ecosystem of the Reagan Era? Probably, and Fonda’s past would have made it impossible to reinvent herself as a purely apolitical workout guru even if she’d tried. She didn’t, but she also moved away from her to meld politics and entertainment. That practice belonged to another time, a looser, more casual kind of time when pot smoke wafted freely, and a movie could be open about trying to raise awareness and affect change and star the world’s most popular country singer and land on the cover of People magazine in the process. And that time was over.

Next: Cutter’s Way

Great piece. Looks like *someone* poured himself a cup of ambition this morning.

I think I saw this about 40 times when I was a kid. This was in the early days of HBO, when you could see this movie, followed by Friday the 13th, at 3:00pm.