The ‘80s in 40: ‘Urban Cowboy’ (June 18, 1980)

A chronological journey through '80s movies (and '80s culture) continues with a film about changing gender roles, identity crises, and a mechanical bull.

Playing a fools game, hopin' to win

And tellin' those sweet lies and losin' again

— Johnny Lee, “Lookin’ For Love”

In 1975 Waylon Jennings topped the country charts with “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way,” a swaggering single that suggested country music, now overrun with “rhinestone suits and new shiny cars,” had lost its way. Jennings doesn’t let himself off the hook, lumping himself in with the rest of the industry, but he still took steps to set himself and his music apart. By the mid-’70s, he’d earned a hard-fought degree of independence and the freedom to record rough-edged country out of step with the polished Nashville sound. In 1976, he’d join Willie Nelson, Jessie Colter, and Tompall Glasser on the compilation Wanted! The Outlaws, a surprise best-seller that became a kind of statement of purpose for what would be known as a movement, outlaw country, and an inspiration for others wanting to follow in their paths or, better yet, blaze their own.

By the end of the decade, Jennings could be heard singing the theme and serving as narrator on CBS’s The Dukes of Hazzard, a cornpone but incredibly popular action comedy show that traded in the hoariest cliches about rural America this side of Hee-Haw and set it all to a twanging soundtrack.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

One fact doesn’t invalidate the other. Jennings stayed the course artistically, and if any country artist could thread the needle between popular taste and traditional country songcraft, it was Jennings and his like-minded contemporaries. But as the ‘70s turned into the ’80s, the cultural tides at least partly responsible for everything from the popularity of the song “Convoy” to the election of Georgia’s Jimmy Carter kept pushing even the most determinedly traditional country artists toward the mainstream. Wanted! The Outlaws was country’s first platinum album, but it wouldn’t be the last. And if ragged cusses like Jennings, Nelson, and the boys (and girls) could find that kind of widespread success, just imagine what kind of success an artist who wanted to cross over could enjoy.

Even then, it didn’t take that much imagination. Country music had been crossing over in one form or another for as long as it existed. The 1970s just seemed to accelerate the process with the rise of easy California country rock and the pop success of songs like Glenn Campbell’s “Rhinestone Cowboy,” a hit the same year as Jennings’ dismayed tribute to all that Hank Williams represented (and ‘70s Nashville wasn’t.) Campbell, who’d done double duty as both a musician and variety show host years before cutting what would become one of his signature songs, was far from alone. Dolly Parton, after securing her own independence from musical partner Porter Wagoner, became a national icon in the 1970s, charting with songs that had one foot in country and the other in pop without alienating either audience. A once regional music had gone global, and inevitably suffered something of an identity crisis in the process. In 1973, Olivia Newton-John, an Australian, won the Best Female Country Vocal Grammy. The next year, the Country Music Association named her Female Vocalist of the year. What was country music if not the sounds of rural and western America? What was country music without, well, the country that spawned it?

Set largely in the Houston nightclub Gilley’s, a kind of honky tonk on steroids that served as the go-to spot for city folk with country hearts and a yen for booze, romance, and fistfights, Urban Cowboy didn’t resolve this identity crisis so much as confirm it. The film makes good on its poster’s “Hard hat days and honky-tonk nights,” following the young Buford “Bud” Davis (John Travolta) as he leaves the farm to find work at a Houston oil refinery and love and music at Gilley’s. He also finds many of his kind: rural transplants trying to bring a bit of the life they left behind into new surroundings, and into an era that often felt at odds with that life’s traditions.

Adapted from Aaron Latham’s 1978 Esquire article “The Ballad of the Urban Cowboy: America’s Search for True Grit” by Lathan and director James Bridges, Urban Cowboy attempts to dramatize that tension via the story of Bud’s romance with Sissy (Debra Winger), a Gilley’s habitué who captures his eye and, in short order, becomes his wife. But tensions mount as they carve out a life together in a nearby trailer park, tensions brought to a head by Gilley’s’ acquisition of a mechanical bull. Sissy wants to ride it. Bud sees that as his domain. That might strike us now as a too-cute symbol of changing gender norms, but, per Lathan's original piece, it has roots in real honky-tonk life. Gilley’s really did popularize the mechanical bull by letting customers ride a machine previously reserved for rodeo competitors in training. Not all the cowboys who drank there approved of cowgirls getting in on the action.

Bridges captures the allure of Gilley’s and the other contemporary honky-tonks it represented (and the many the film would inspire into existence). At work, Bud’s just another interchangeable worker in an almost dystopian industrial landscape doing a job that makes him feel less like himself. (He has to shave off his beard before he can even get hired at the refinery’s lowest position.) At Gilley’s, he can be who he wants to–and, like everyone else there, he wants to be a cowboy. Or as long as the music plays, he can pretend he is, and others can pretend along. There’s not a lot of glamour in Bud and Sissy’s life, but the film shoots their first dance as a sweaty, sensuous coupling that’s as intimate as a love scene. The rest of the world, the parts that don’t allow them to be a cowboy and cowgirl clinging to each other, falls away, at least as long as the song keeps playing.

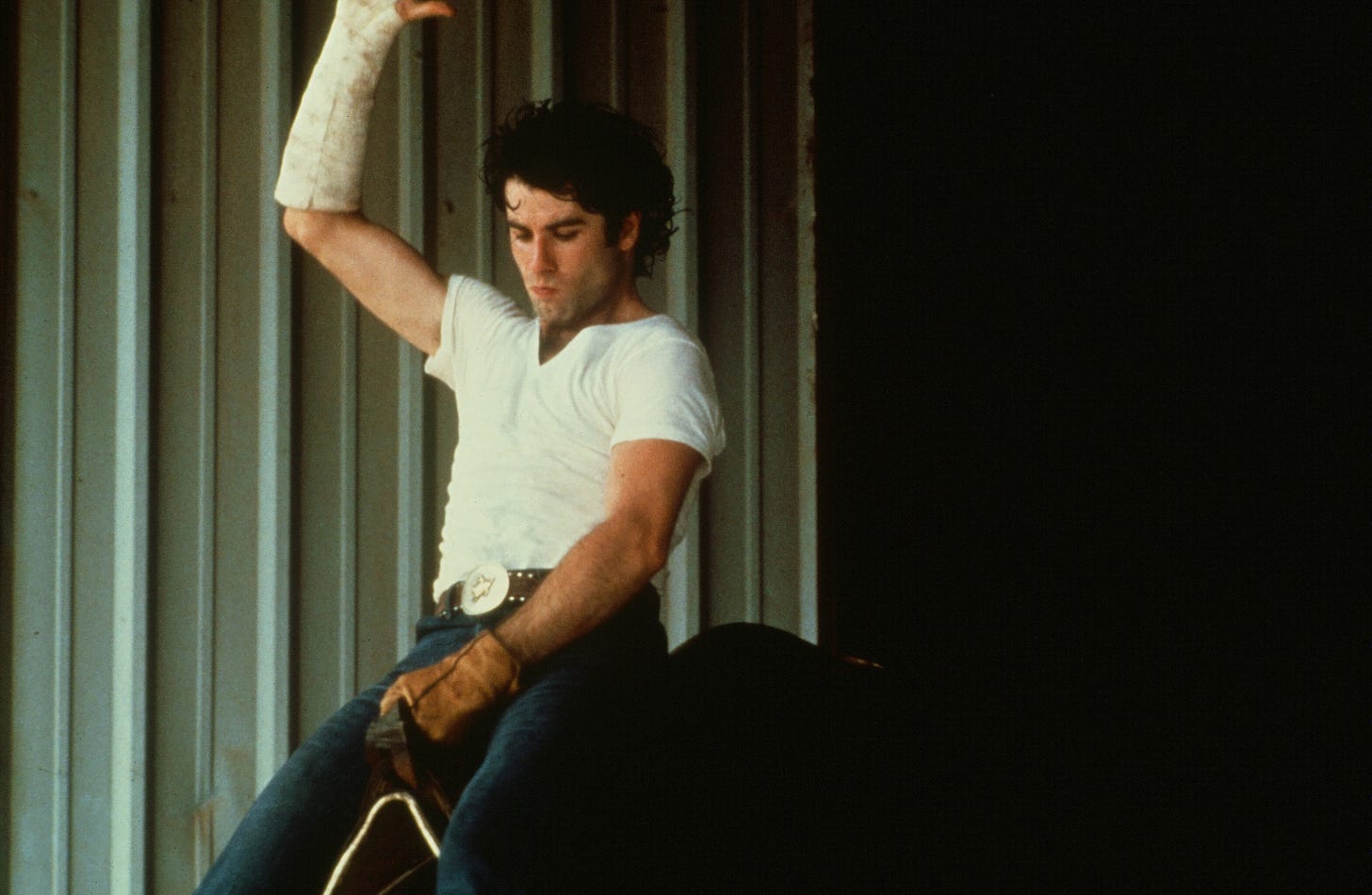

In some respects, this was familiar turf for Travolta, who found breakthrough success with Saturday Night Fever, another narrative film inspired by a (nominally) non-fiction piece about a music-based subculture in which aspiring tough guys grooved beautifully to the latest beats but, once off the dance floor, were disastrous to the women around them. (That film’s inspiration, unlike Urban Cowboy’s, was later exposed as largely invented.) Urban Cowboy doesn’t just trade pop chart-friendly disco for commercial country, but it similarly casts Travolta as a young man who can never quite dance his frustrations away. And Bud, like Tony Manero, isn’t all that likable. He slaps Sissy in the lead-up to proposing, and he slaps her again later, because he thinks that’s what men do. Urban Cowboy doesn’t ask us to approve of this behavior, but it does seem to expect us to feel for him.

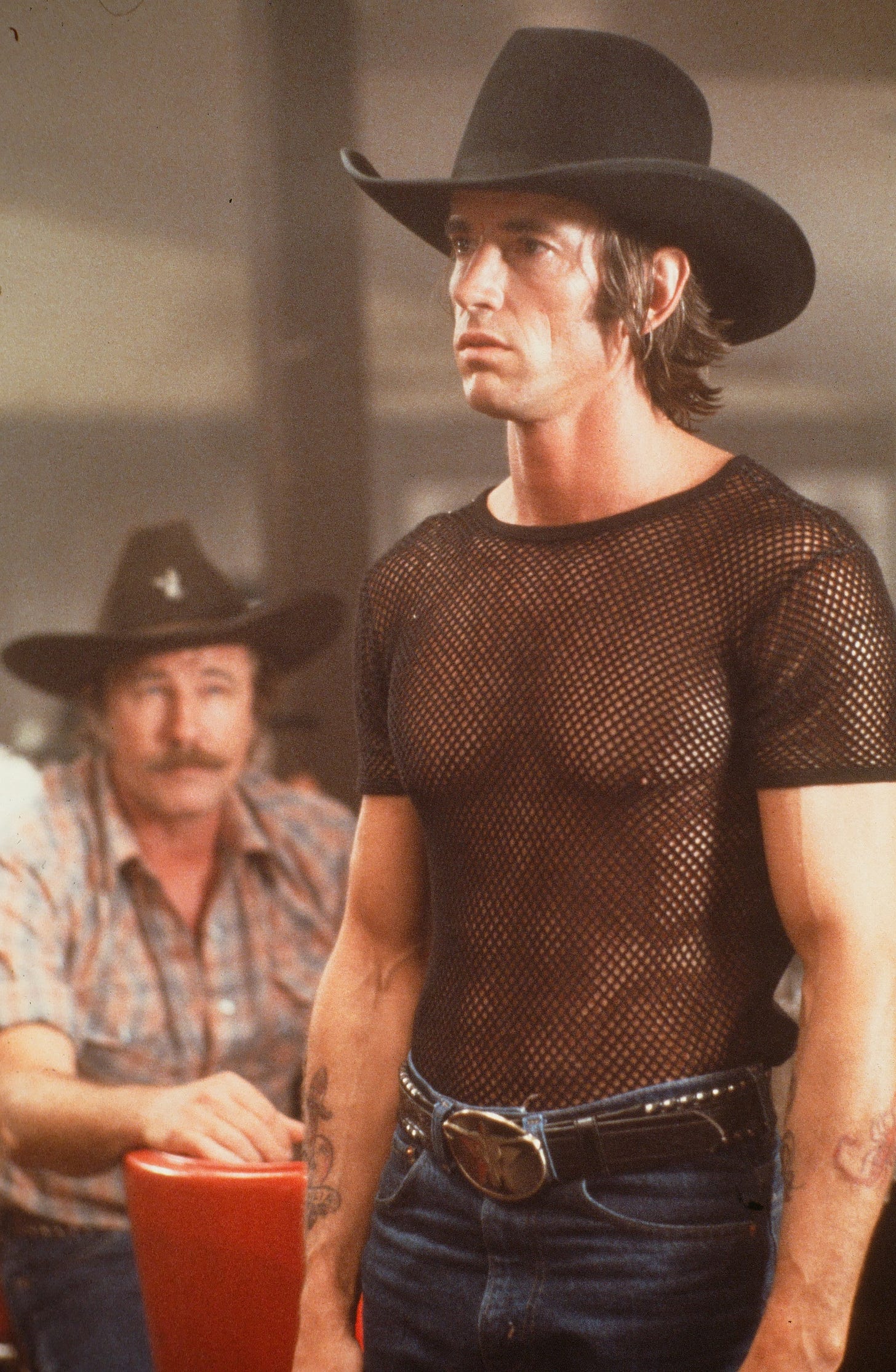

That’s at least partly because Bud looks like John Travolta, whose early career is filled with characters who behave shittily but are just too beautiful for other characters (and audience members) not to forgive. (See also Tony Manero, Danny Zuko, and Vinnie Barbarino.) And it’s at least partly because after Bud and Sissy split up when Sissy’s insistence on riding the mechanical bull widens preexisting fissures in their marriage. Sissy falls in with the even more abusive Wes Hightower (Scott Glenn), an ex-con hired to work the mechanical bull, a man so confident he shows up wearing a see-through black mesh shirt while surrounded by Western finery. He’s unfaithful and physically abusive but encouraging of her mechanical bull-riding enthusiasm, memorably demonstrated in a sensual, acrobatic routine Winger performs without a double. (This would prove to be her breakthrough role.) It’s Bud who strays first, drawn away by Pam (Madolyn Smith), an oil executive’s daughter with a taste for cowboys. Her father goes to an analyst three times a week but Pam, as she tells Bud, likes “men with simple values. I like ‘em independent, self-reliant, brave, strong, direct, and open.”

Pam’s essentially summarizing the thesis statement of Latham’s original article, in which he writes:

the beer joint bull rider, is as uncertain about where his life is going as America is confused about where it wants to go. And when America is confused, it turns to its most durable myth: the cowboy. As the country grows more and more complex, it seems to need simpler and simpler values: something like the Cowboy Code. According to this code, a cowboy is independent, self-reliant, brave, strong, direct, and open. All of which he can demonstrate by dancing the cotton-eyed Joe with the cowgirls, punching the punching bag, and riding the bull at Gilley’s. In these anxious days, some Americans have turned for salvation to God, others have turned to fad prophets, but more and more people are turning to the cowboy hat.

But is Bud a “real cowboy?” That’s the question Sissy asks when they first meet, and it’s one the film never really answers, unless the couple’s climactic reconciliation counts. Maybe there is no answer, not in 1978, when Latham first covered Gilley’s life, and not in 1980, when moviegoers made Urban Cowboy a hit. Soon a cowboy actor would be in the White House on promises to return America to a simpler time no more rooted in reality than the cowboy fantasy’s of Gilley’s patrons. Maybe, when it came to cowboys, make believe was as good as pretend. Maybe just acting the part could be enough.

Perhaps even more importantly, the film’s four-sided soundtrack, like Wanted: The Outlaws and Saturday Night Fever, became a platinum sensation, filling the airwaves with Johnny Lee’s “Lookin’ For Love,” Kenny Rogers’ “Love the World Away,” a cover of “Stand By Me” performed by Mickey Gilley (the country star and Jerry Lee Lewis cousin who lent his name to the club), and more. In the years that followed, Nashville’s Music Row would perform pendulum swings between pop and tradition, but it would never be niche again. That development undoubtedly predates Urban Cowboy, but the film marks a convenient point of no return.

Hank surely wouldn’t have done it that way. But Hank wasn’t around, and country was coming to the mainstream just as unavoidably as the mainstream was coming to country. Were places like Gilley’s faddish oddities or, as Lathan and the film suggested, symptomatic of an America trying to figure out where it was going and struggling to retrofit old icons for a new age? Of the Urban Cowboy Latham writes, “in a world where machines have replaced every animal but himself, and he is threatened. In his boots and jeans, the urban cowboy tries to get a grip on and ride an America that, like his bull, is mechanized. He can never tame it, but he has the illusion of doing so.” Maybe both the rhinestone-clad urban cowboys and Jennings and his outlaw pals were chasing ghosts, old ways of living they couldn't hold to in a world that was moving on.

If I were the sort of writer inclined to including a lot of footnotes I would have included one about this Stella (sister of Dolly) Parton song defending Olivia Newton John's right to sing country music. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEyR2Uu4Unc

Side note that while Charlie Daniels was kinda nuts (and nuttily rightwing), boy does the Charlie Daniels band cook.