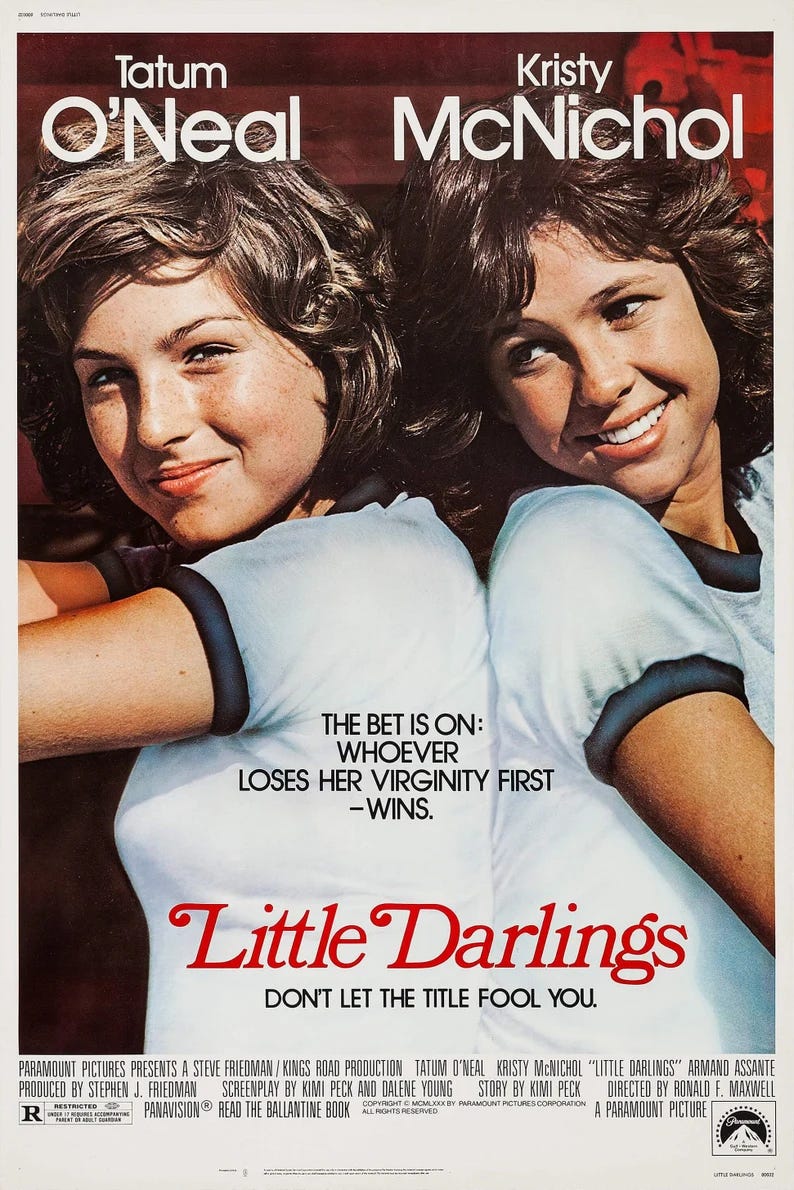

The ’80s in 40: ‘Little Darlings’ (March 21, 1980)

A chronological history of the 1980s via 40 films — one from each quarter of each year — kicks off with a camp comedy about youth gone (mildly) wild.

We were too young to be hippies

Missed out on the love

— Victoria Williams, “Summer of Drugs”

As the 1970s turned into the 1980s one film after another addressed the same question: Are the kids all right? The answers weren’t always comforting. Released (if just barely) in the spring of 1979, Jonathan Kaplan’s Over the Edge depicts restless, denim jacket-clad youth wandering the suburbs of a planned community near Denver, looking for cheap thrills from drugs, vandalism, and guns — a search that culminates in a tense, violent stand-off at a high school. “They were old enough to know better… but too young to care,” the trailer warned, summarizing an attitude that powered films that otherwise didn’t much resemble one another.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

The family comedy The Bad News Bears (1976), for instance, makes a joke of kids’ free use of profanity, racial slurs, cigarettes, and liquor. Other films didn’t find such anti-social behavior nearly as funny, tapping into the era’s anxiety about changing mores. In the gangland fantasia of Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979), Over the Edge-types of every race, creed, and sexual orientation have all but taken over New York. In Adrian Lyne’s Foxes (1980) tragedy finds a quartet of under-supervised teens in the San Fernando Valley. A decade on from the end of the 1960s, the movies kept suggesting there might be consequences for all that loosening up and letting go.

Surely, nothing could shock a moviegoing public used to such material, right?

Wrong. On April 3, 1980, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch carved nearly a third of a page for an item about “Pete,” a divorced father who recently took his daughter to the new comedy Little Darlings because he saw, in the words of Post-Dispatch staffer Jeff Meyers, “an ad for a movie starring sweet, adorable Tatum O’Neal and wholesome Kristy McNichol, perhaps the only starlets in Hollywood who have yet to take off their clothes for Playboy magazine.” So what was the problem? With no warning — apart from the film’s R-rating, but who looks at those? — Pete and his daughter found themselves watching a comedy in which the rich, snooty Ferris Whitney (O’Neal) and the chain-smoking, wrong-side-of-the-tracks Angel Bright (McNichol) compete to see who can first lose her virginity.

“I was fooled into taking my daughter to that picture,” Pete laments, “and I’m sure a lot of parents are going to be, too. It isn’t a cutesy picture; the subject should be treated seriously, but they made it seem that any girl who doesn’t lose her virginity by 15 is some kind of nerd.” Though Pete’s right about the plot, his reading of Little Darlings doesn’t quite square with the film itself, which treats the subject with as much nuance as can be expected of a summer camp comedy whose centerpiece is a protracted (and disgusting) food fight.

That it was girls, not boys, doing the leering and food fighting seems to have been at the heart of the objections. Longtime Baltimore Sun critic R.H. Gardner found irony in “the fact that the film, which portrays the sexual preoccupations of pubescent female on a raunchy locker-room level, should have been written by two women,” Kimi Peck and Daelene Young, the latter a veteran of TV movies like Dawn: Portrait of a Teenage Runaway who’d go on to a long career alternating between TV and features. The review concludes with the declaration that this depiction of “angel-faced ‘little darlings’ carrying on like a bunch of sailors in desperate need of shore leave constitutes perhaps the ultimate comment on the peculiar values of the period in which we live.”

But what, exactly, were those values? Subtitled “Erotic ’80s,” the current season of Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember This podcast is exploring the peculiar sexual landscape of that decade’s movies. The season’s second episode focuses on 1979, Bo Derek, and Blake Edwards’ 10, finding it to be, to borrow a title from later in the decade, a land of confusion. 10 became a surprise hit with audiences who, like Moore’s hero, were intrigued by the possibilities opened up by the sexual revolution–though perhaps not quite driven to his extremity of libidinal madness–but ultimately wanted to be reassured that the old, traditional ways remained the best.

Early 1980 was a moment filled with mixed messages. Little Darlings played theaters alongside Foxes and shortly after Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo. The former kills off a wild child character played by Cherrie Currie of the Runaways, a recently disbanded all-female rock band Currie had joined at 15 and whose sexually aggressive image was crafted in large part by a male Svengali figure. The latter presents a neon-drenched Los Angeles pulsing with sexual possibilities and an understanding that sex could be treated as just another-high end consumer item, all before steering Richard Gere’s protagonist toward righteousness and redemption in the arms of the woman who loves him. In the lobby, moviegoers might have heard The Knack’s lingering 1979 hit “Good Girls Don’t,” with the chorus punchline “but I do.”

What’s a girl like poor Pete’s daughter to think of all this mixed messaging? Though filled with juvenile gags, Little Darlings takes its characters’ confusion seriously. At Camp Little Wolf, the most poorly supervised summer camp outside the greater Crystal Lake region, Ferris and Angel join a spectrum of broadly drawn teen types, from a mature-beyond-her-years kid who claims to be engaged, to a pre-pubescent scamp eager to run with the big girls, to a second-generation flower child ready to dispense vitamins and other herbal remedies (Cynthia Nixon, who here resembles a lost Brady sister), to a heavyset girl whose personality is defined entirely her weight. (OK, it’s a limited sort of spectrum. They’re all white.) They’re united in one respect, however: after Ferris and Angel trade blows and insults, everyone eagerly cheers on their virginity-losing contest.

Ferris sets her sights on Gary (Armand Assante), a handsome counselor who ultimately draws a line he doesn’t allow her to cross, but only after letting her hang out alone with him in his booze-filled cabin and admitting he finds her attractive. Meanwhile, Angel eyes Randy (Matt Dillon, less than a year after his Over the Edge appearance), a beer-swilling bad boy from a nearby camp. They meet at an abandoned shelter by the lake where, after a false start and some arguing, they have sex. In the aftermath, both fudge the truth about their experiences. And both seem unsure how to feel about what’s transpired.

For all the crassness of the set-up and the gags that come withit, the film exhibits a surprising tenderness. A sequence in which the girls steal a vehicle — again, it’s an extremely poorly supervised camp — and break into a gas station bathroom to make off with its condom machine captures both the its crudeness and its heart. These girls are “bad” enough to steal a bunch of rubbers but (mostly) don’t have any use for them. They’re all stuck in a kind of limbo, educated in the facts of life but too immature to sort through the meaning. (“They were old enough to know better… but too young to care.”) Little Darlings doesn’t judge Ferris and Angel for their actions. It mostly just mirrors their melancholy pensiveness at summer’s end.

The film didn’t win many raves — a typical headline “Little Darlings is a four-letter film: J-U-N-K” — but it found some admirers. In the Atlanta Constitution, Eleanor Ringel called it a “delightful and refreshingly real look at life among today’s teenage girls'' and noted that it “never becomes smirky or condescending.” Though he couldn’t go higher than two stars, accurately pointing out that Little Darlings wants to be at once “a fairly serious film about teenagers and sex, but also a box-office winner like National Lampoon’s Animal House or Meatballs,” Roger Ebert echoed some of those sentiments in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times and noted its success “in treating the awesome and scary subject of sexual initiation with some of the dignity it deserves.”

That can't make Little Darlings great, but it does make it unusual. It would also make it an outlier — though not the only outlier — among the era’s teen comedies, which were rarely interested sexual ambivalence, girls’ thoughts, or female desires.

So what happened to those kids, the wandering, shaggy, destructive youth of the turn of the decade and their contemporaries? Mostly, they grew up, and turned into ’80s adults, with the decade laid out in front of them waiting to be claimed as their own. As we’ll explore in future entries, many of the films that followed Little Darlings and its companions tell their stories and take them places unimagined back in the troubled Colorado suburbs, parent-less Valley homes, shores of Camp Little Wolf, and wherever else restless ’70s kids looked to a future that soon assumed shapes they’d never imagined.

I was 12 when this came out. I well remember -- because of indoctrination at home and in church -- how scary movies like this were to me. They were created by Hollywood/Communists/Satan in a deliberate bid to defile and destroy young souls like mine. Any theater where they played was the antechamber of hell, and what awaited behind that blue velvet curtain was scarier than any haunted house could ever be. That went for everything from "Little Darlings" and "10" to "Prophecy" and "The Amityville Horror." I specifically remember how bitterly disappointed I was, like divorced dad "Pete," that sweet Tatum O'Neal had been corrupted into making a movie like this. (Kristy McNichol was already a lost cause since she was on "Family," a TV series my parents forbade me to watch.)

Now, having been reminded of all this, I'm eager to finally see "Little Darlings" and shake my head at everything I was taught to be afraid of as a kid. And I'm also reminded, depressingly, of how little has changed in the realm of fearmongering over the past four decades.

I feel like this post got lost in a bunch of other releases, and the news cycle that week. Are we getting back to this feature? (“80s in 40”). Seems like a great idea and was looking forward to it.