The '80s in 40: ‘Heaven’s Gate’ (April 29, 1981)

A notorious flop in its day, Michael Cimino's third film has been reclaimed as a classic. But its failure had lingering effects on both its creator's career and the movie business as a whole.

The ’80s in 40 revisits the decade of the 1980s choosing four movies a year, one from each quarter. This entry covers the first three months of 1981.

Director Michael Cimino filled the years after the high-profile commercial collapse and critical drubbing of Heaven’s Gate with false starts, failures, and finally a long retreat during which he wrote screenplays that would never be filmed and novels that would only be released in France, if they were released at all. During those first years, when he could still find work, if not always the work he wanted, Cimino took on a few collaborators, including writers Raymond Carver and Tess Gallagher. With the pair, Cimino reworked a Russian screenplay about the life of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, then collaborated on a second screenplay about juvenile delinquents journeying through America. Both efforts ended up on a shelf, but the partnership did yield one completed work, Carver’s poem “The Juggler at Heaven’s Gate.”

The poem was inspired by Carver and Gallagher’s admiration for Heaven’s Gate and specifically by a moment in which Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson), a Harvard graduate living in the frontier town of Sweetwater, where he serves as marshal in Wyoming’s Johnson County, has a series of intense conversations over coffee in an establishment owned by the local businessman John H. Bridges (Jeff Bridges). These conclude with a conversation with Nate Champion (Christopher Walken), a friend, of sorts, who makes up the third point of a love triangle with Ella (Isabelle Huppert), the proprietor of the local bordello. But Champion’s now working as an assassin for the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, a powerful organization with a government-sanctioned kill list of Johnson County residents they deem undesirable, mostly Eastern European immigrants whose existence the stock growers see as a threat to their thriving business.

It’s a pivotal scene, one that sets the terms of the conflict that will play out over the rest of the film, but Carver’s poem focuses instead on a background player framed by the window over Averill’s shoulder, a man performing juggling tricks, unaware that a drama tied to the fate of Sweetwater itself is unfolding mere steps away.

Here’s how Carver’s poem ends:

That tiny spectacle. At this minute, Ella's plight

or the fate of the emigrants

is not nearly so important as this juggler's exploits.

How'd he get into the act, anyway? What's his story?

That's the story I want to know. Anybody

can wear a gun and swagger around. Or fall in love

with somebody who loves somebody else. But to juggle

for God's sake! To give your life to that.

To go with that. Juggling.

Carver’s right: just the image of the juggler juggling away makes it easy to want to know his story. The juggler’s presence is an unnecessary detail, in the sense that he adds nothing to advance the story. But it’s also the sort of detail that’s crucial to Heaven’s Gate, an element that suggests we’re watching a rich and fully inhabited world, one in which gunslingers and land barons and other familiar figures might drive the plot but whose boundaries extend beyond them and their concerns.

Heaven’s Gate is filled with such touches and brims with life in other ways. From the citizens milling about Sweetwater to an early sequence of Averill graduating from college — another practically unnecessary but artistically essential component of the film — Cimino fills the film with extras that give the film a kind of time machine quality. Seemingly no detail of 1890 Wyoming has been left out. Even bathed in the light of Vilmos Zsigmond’s extraordinary cinematography, it may be hard to read the fine print on the playbills that line the walls of the Heavens Gate roller rink that gives the film its title or the newspapers Champion uses as wallpaper, but there’s no reason to doubt they’re as scrupulously detailed as every other element of the movie.

None of this, famously, came cheap. Heaven’s Gate’s budget overruns made it a story before it was even completed. They’re chronicled at length in Final Cut, an entertaining and crisply written account of the film’s production written by United Artists exec Steven Bach, whose frequent self-deprecation almost but doesn’t quite mask the book’s self-serving elements.* Bach worked closely with Cimino but still discusses him as a cryptic figure, a difficult perfectionist who did his best to put up barriers between himself and his employers. That unknowability isn’t entirely an accident. Charles Elton’s 2022 biography Cimino depicts the director as a deeply private person with a habit of compartmentalizing elements of his private life and obscuring and fabricating his past.

One of those fabrications, a claim to have been a medic attached to a Green Beret unit, had contributed to a backlash against Cimino that developed after his 1978 Vietnam drama, The Deer Hunter, dominated the Oscars. But mostly, it was the money. The press treated the cost as an obscenity and, 40 years later in a Hollywood dominated by budgets unthinkable during Heaven’s Gate’s production (even adjusted for inflation), it becomes hard to see why. Writing about the film for The A.V. Club in 2019, Ignaty Vishnevetsky summed it up nearly: “This may be theoretically offensive to accountants; it is not clear why it should offend anyone else.”

The poor reviews that accompanied the premiere of Heaven’s Gate in New York in November 1980, after which it was pulled from theaters and recut, were just more thunderclaps in a perfect storm, all but guaranteeing its failure. Its arrival in theaters, shortened by Cimino by 70 minutes the following April where it was met with indifference, became that storm’s last rumbles.

It’s been fascinating to watch the pendulum of appreciation swing so far in the other direction over the past few decades, particularly since the 2012 release of a restored version of Cimino’s original cut of the film. These days, it’s far easier to find those who regard the film as a masterpiece than a boondoggle. I can’t quite get there myself. The film’s central love triangle never works for me and while I fully believe that Heaven’s Gate needs to be long to work, I find its pacing hampers it at times. But I’m far more sympathetic to the masterpiece camp than the other side. To my eyes it’s masterpiece-ish. Heaven’s Gate shares, and expands, on the best qualities of The Deer Hunter by depicting a fractious but functional community facing an apocalyptic threat. (Say what you will about excesses of The Deer Hunter’s Vietnam scenes, the homeland scenes that bookend the film are devastating.)

But even if I didn’t admire the film as an artistic achievement, I’d still be sympathetic to it, if only for the consequences both for Cimino and for Hollywood filmmaking. Cimino let his artistic ambitions take the film where they would. Using house money to do so caught up with him before anyone even laid eyes on the movie, but the talent and daring are impossible to miss, even if plenty of critics didn’t see it at the time and audiences largely didn’t see it at all. (A moving shot of a violinist, played by score composer David Mansfield, performing on roller skates, must have required a Jackie Chan-like combination of ability and luck to pull off. It was also cut from the shorter version released to theaters.) For his perceived sins, Cimino ended up on the sidelines. He made four more films, none of them passion projects, between 1981 and 1996**, followed only a single short before his death in 2016. His reputation rests on his first three films — Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, The Deer Hunter, and Heaven’s Gate — but these now look like chapters in a story cut short too soon.

Heaven’s Gate is a closing chapter of another kind, too. It’s hard to pinpoint the end of the New Hollywood of the 1970s (though you could do worse than One From the Heart’s Radio City Music Hall premiere in January 1982). Heaven’s Gate may not have brought that era to a close, but it certainly hastened it. Bach overstates the film’s role in ending the already troubled United Artists in Final Cut (which, in its current edition, bears the subtitle “Art, Money, And Ego in the Making of Heaven’s Gate, the Film that Sank United Artists”) but Heaven’s Gate’s failure contributed to a prevailing sense that directors had too much power and that studios, as they increasingly became part of global conglomerates, had better ways of serving the bottom line than indulging art for art’s sake— the motto of MGM, the studio that bought United Artists less than a month after Heaven’s Gate wide release. MGM was owned at the time by Kirk Kerkorian, who would essentially sell and repurchase various parts of the company several times over the next few decades.

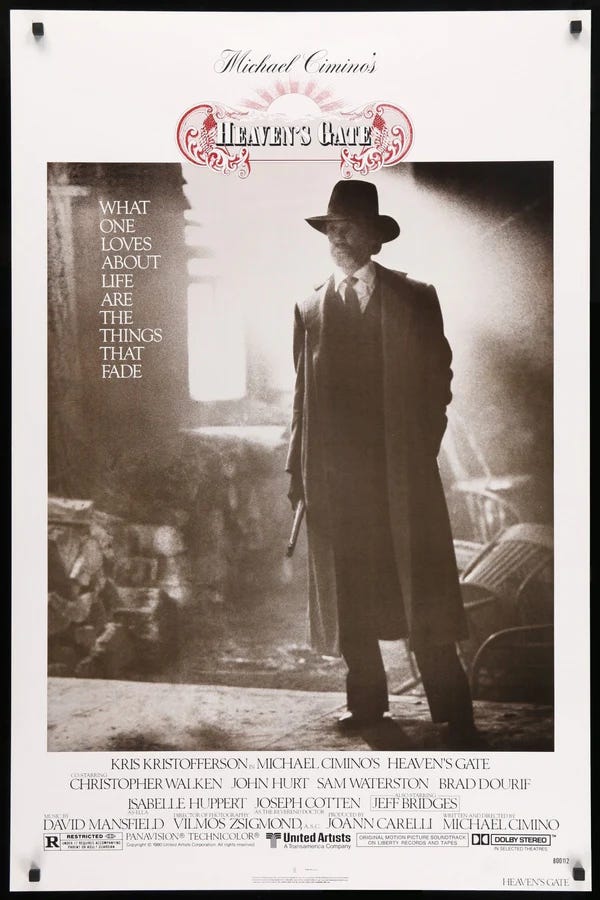

Still, Heaven’s Gate has endured in ways no one could have predicted in 1981. That it’s a film about the inevitable encroachment of a capitalist plutocracy on what was once open terrain lends another layer of resonance. That there could never be another Heaven’s Gate — so long, so expensive, so difficult — might have felt like a relief to many at the time. Now it seems like a sign that the longest period of artistic freedom American filmmakers would ever enjoy was nearing its end. When Heaven’s Gate played nationwide, it was accompanied by a poster with the gauzy image of Huppert and Kristofferson locked in an embrace that bore the tagline “The only thing greater than their passion for America… was their passion for each other.” This took the place of the original poster, a stark, black and white image of Kristofferson bathed in sunlight. It bore a different tagline: “What one loves about life are the things that fade.”

Next: Stripes

Previous Entries in this Series:

Cutter’s Way (March 1981)

9 to 5 (December 1980)

Urban Cowboy (June 1980)

Ordinary People (September 1980)

Little Darlings (March 1980)

* And sometimes Bach just shoots himself in the foot, as in a long sequence questioning Huppert’s suitability for the film, complaints that begin with her English but extend to detailed thoughts about her face and body.

** I have to confess that all but the last, The Sunchaser, remains unknown territory to me. Nothing about the other Heaven’s Gate follow-ups has seemed enticing, but I should probably correct that someday.

it's not a Masterpiece, but it has so much going for it that I would still almost call it essential viewing. it's really hard to imagine how people reacted so negatively to the original cut upon release. (I never saw the shorter version, but it's easy to imagine cutting 70 min would remove a lot of it's appeal, which is to bathe you in this world)

This is a great series.