The ‘80s in 40: ‘Poltergeist’ (June 4, 1982)

There's something amiss in the carefully planned suburbs of this horror classic.

The ‘80s in 40 revisits the decade of the 1980s choosing four movies a year, one from each quarter. This entry covers the second quarter of 1982.

Those of a certain age might have encountered Poltergeist as a rumor before they knew it as a film. I know my elementary school’s playground buzzed with whispers of the “movie where the guy rips his face off.” And, indeed, Poltergeist does have such a scene and it is remarkably grisly, so grisly that it raises the question of how, in this pre-PG-13 era, Poltergeist arrived in theaters rated PG. Other PG-rated movies released in 1982: Annie, Gandhi, and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. That Poltergeist’s credits list E.T. director Steven Spielberg as writer and producer undoubtedly goes a long way in explaining how the film got away with such a scene that, even though it’s soon revealed to be a supernatural hallucination, still seems designed to induce nightmares.

Of course, that’s not the only such moment in Poltergeist, as those who dared to check out the source of all those playground rumors found out. There’s the gnarly, malevolent tree, the grinning clown toy, the swimming pool filled with corpses, and more. If a sadistic filmmaker were to design a horror movie for the sole purpose of freaking out young viewers by slipping it into theaters with a misleading rating, it would probably look a lot like Poltergeist.

That said, not a lot of horror movies looked like Poltergeist in 1982, or look like it now. Its core novelty comes from transplanting an old story—this house is haunted!—to a fresh setting, the American suburbs that were still finding new places to sprawl as the 1970s turned into the 1980s. The film’s California planned community, Cuesta Verde, is designed to be a safe place for nice people, one that offers a fresh start away from the past, and, though this remains unspoken, the city from which Cuesta Verde’s overwhelmingly white residents have fled. But the past has ways of reasserting itself and safe places aren’t always as safe as they appear—not even lived-in split-levels filled with trappings specific to the era. Poltergeist’s central family, the Freelings, make their home in rooms filled with catalog-bought furniture, Atari cartridges, and Star Wars toys. Its modern conveniences include two TVs and a gleaming kitchen. None of this will keep them safe.

Poltergeist treats the suburbs with braided suspicion. An early scene, one that opens with a dissolve from the Freelings’ kitchen to an identical room in a model home, finds Steve Freeling (Craig T. Nelson), the star agent for Cuesta Verde’s development company, mid-routine as he attempts to move to another home. He has the patter down, but it’s clear his heart isn’t in it when tries to address his clients’ concern that one house looks just like all the others. Steve’s lived in Cuesta Verde from its founding in 1976 and, per his boss Lewis Teague (James Karen), has done more than anyone to make it a success. But at this moment, even before his life has taken a turn for the seriously weird with the abduction of his daughter Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke), he doesn’t seem to believe his own pitch (though this doesn’t mean he won’t make the sale). And even before it’s revealed that the Freelings and their neighbors have built their homes on a former cemetery whose relocation plan didn’t include moving the dead, Poltergeist depicts Cuesta Verde’s mere existence as an act of hubris. It’s been sold as a place of escape—from grime and unpredictability and the prejudiced fears they won’t say out loud—but it’s only brought them headlong into other, more real if less tangible, threats.

It’s impossible to talk about Poltergeist without discussing its origins and production, if only briefly. The film’s roots date back to Dark Skies, an alien invasion film Spielberg never made. Spielberg received a story credit for the film and a screenplay credit alongside Michael Grais and Mark Victor, though it was director Tobe Hooper who steered it away from aliens and toward ghosts. For reasons covered thoroughly elsewhere and too complicated to get into here, Spielberg has overshadowed Hooper to the point where some have credited him as the film’s real director, though both Hooper and Spielberg have pushed back at this.

Beyond offering some deeply researched context into the making of the film and the paths that brought Spielberg and Hooper to Poltergeist, Jacob Russell’s recent book on the film, called simply Poltergeist and released as part of DieDieDie Books’ series of horror movie monographs, makes an excellent argument that at the very least the talk of Spielberg being the film’s true director is inaccurate, however heavy a role he played. That jibes with my own impression of the film, too. Some shots, especially the “Spielberg face” images, bear the director’s unmistakable stamp, and Hooper worked from Spielberg storyboards. But Hooper was far from technically unskilled, as the masterful The Texas Chain Saw Massacre attests. He certainly wouldn’t be the first director to feel the influence of a powerful producer, but that shouldn’t sideline his contributions.

That said, you can’t easily take Spielberg out of the picture either. Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., Poltergeist, and other Spielberg productions of the era all treat the American suburbs with varying degrees of affection and disdain. A similar suburb becomes a site of wonder in E.T. (which opened just a week later in the remarkable summer of 1982), but also a place where latchkey kids lead an unguided, parentless existence. It’s a home not unlike the Freelings (but smaller) in which Richard Dreyfuss finds himself alienated from his family in Close Encounters. Back to the Future’s ‘80s suburbia exists around an abandoned downtown that, we’ll soon see, once served as the vibrant center of Hill Valley. Did we know what we were doing when we built so many of these places in the years after World War II? Are they really where we want to spend our lives?

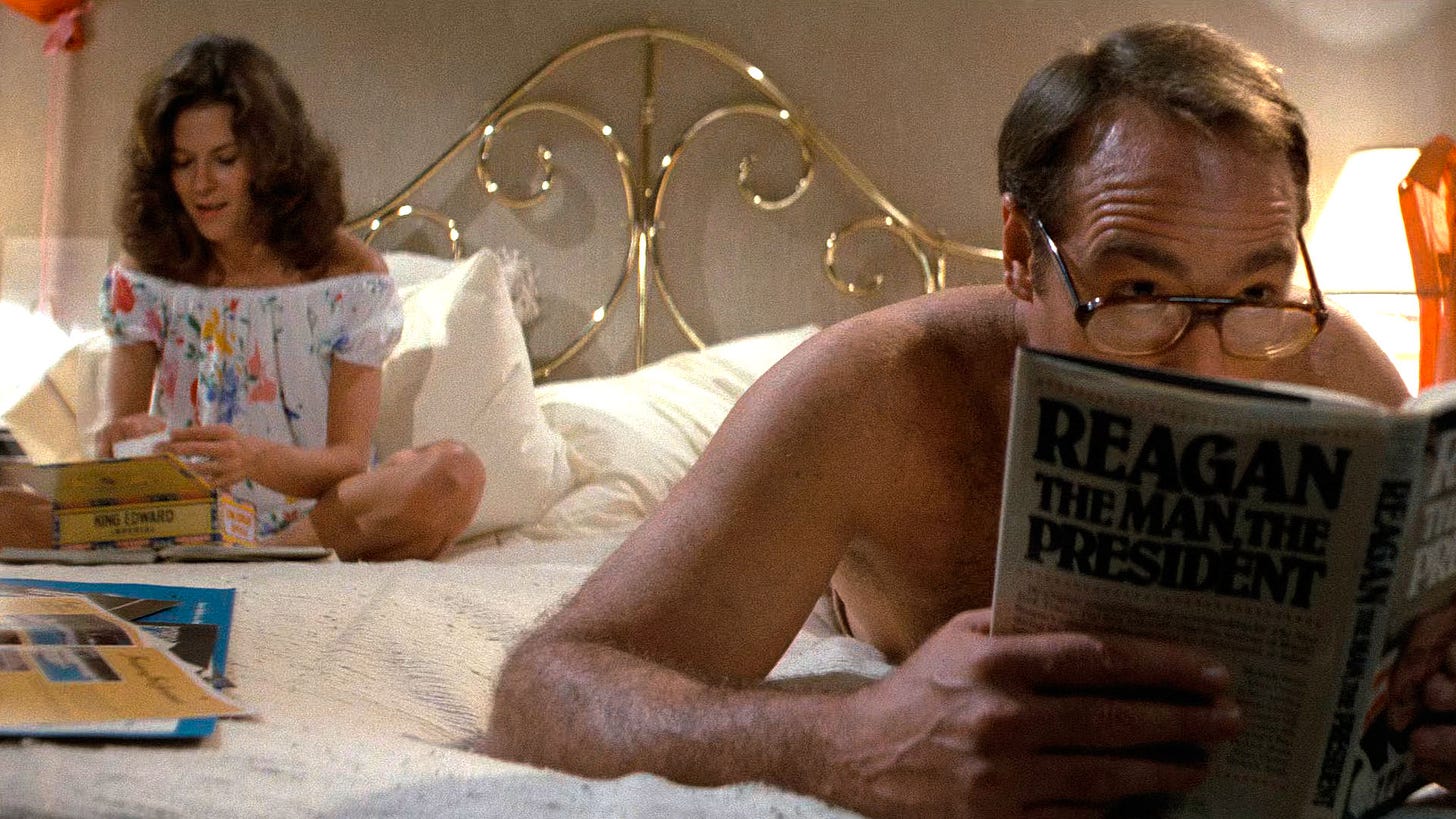

The Freelings may not have had that much of a choice. As the film opens, they seem happy enough and Steve’s marriage to Diane (JoBeth Williams) appears to be rock solid. But that doesn’t mean they’re not without regrets. A scene in which Diane and Steve smoke pot after (they think) the kids have gone to bed appears to be headed in an intimate direction before they’re interrupted, but it’s also built around the couple mockingly acknowledging their faded youth. Later, when strange phenomena start to occur, Diane asks Steve to “reach back into our past when you used to have an open mind, remember that?” Like many Baby Boomers, the ’80s has brought the undeniable approach of middle age and washed them up in a much less wondrous world than they might have dreamed of in the 1960s. Though Diane studies up on Carl Jung as she tokes, Steve’s bedtime reading is a book on Reagan written by a collection of New York Times writers in the early days of his presidency.

Here’s a detail you might have missed, however. (I know I did the first few times I watched the film.) When Steve reaches out to Dr. Lesh (Beatrice Straight), an academic who dabbles in parapsychology, he tells her his wife is 31… no, 32 and his oldest daughter Dana (Dominique Duane) is sixteen. The math makes Diane a teenage mom. Assuming Steve’s around the same age, their time exploring the carefree, experimental 1960s ended sometime between 1965 and 1967. Whatever path brought them to Cuesta Verde, it’s probably not the road they imagined themselves taking when they watched the Beatles play Ed Sullivan. That they were the first to arrive makes sense in that context. Life hurried them to a destination it would take their contemporaries a few more years to reach.

This is also more or less Mrs. Robinson’s story in The Graduate, only transposed up a generation and down a tax bracket or two. But where Mrs. Robinson knows she’s trapped and drinks and fools around in an attempt to escape. Diane and Steve need a supernatural tap on the shoulder to reframe their home as a place of fear rather than shelter, one they need to escape even more urgently than Mrs. Robinson.

A fuzzy kind of metaphysics guides Poltergeist. The malevolent spirit that gives the film its title seems to kidnap Carol Anne out of spite. In whatever between-worlds realm she finds herself she becomes a magnet for restless spirits reluctant to move onto the afterlife. Her return seems to end this, but then the spirit world takes another pass at wiping out the Freelings. Are the bodies beneath the house the root cause of all this or is this a separate problem? Unclear. And it doesn’t really matter. The film’s power comes not from a coherent vision of the spirit world but from the way it turns the Freeling home and material possessions against them and those who would aid them. Toys fly through the air then, later, attempt murder. A steak crawls across the counter. A bathroom heat lamp turns face-meltingly hot (the cause of the film’s most infamous scene).

Then there’s the television, which serves as a kind of gateway between the Freeling house and the other side. A technological wonder when Steve and Diane were growing up it’s become a household fixture for their children, a mechanical device that ought to be free of the superstitions of previous ages. But, like the rest of the Freelings’ home, it’s not, its static filling the room with a flickering glow as creepy as any ghost. (Is it fair to consider the Freeling’s TV set as the inspiration for the haunted technology that would plague Japanese horror films in the decade that followed?)

After Carol Anne’s disappearance, Steve’s attitude toward the suburbs darkens. Unaware of the ghostly crisis, and fearing his star salesman’s recent absence suggests he’s looking for another job, Teague takes him to the top of a nearby hill and asks him what he thinks of the view. “It’s pretty nice if you’re living up here,” Steve says, “but not so great down there in the valley having to look at a bunch of homes cutting into the hillside.”

“Well, you don’t have to live in the valley anymore,” Teague replies. “All of this can be your master bedroom suite. That can be your view.” Teague’s not exactly the devil and this isn’t exactly a high mountain looking over all the kingdoms of the world, but Steve recognizes it as a temptation he should resist, even before Teague tells him they’ve made arrangements to relocate the nearby cemetery. He knows there’s something wrong with his house in the valley, and maybe all the houses in the valley and, if so, this proposed “Phase V” of Teague’s development plan will only spread it further.

In the end, Steve and Diane get their daughter back and escape their home moments before it implodes, leaving behind only an empty lot, as if the universe was attempting to undo a mistake. The Freelings spend the night at a nearby Holiday Inn, but what about the next day? Phase V might not go according to Teague’s plan, but that just means it will find another spot, followed inevitably by Phases VI, VII, and VIII until the sprawl eats up every acre, unconcerned with what lies beneath the foundation. Where else is there left to go?

Next: Fast Times at Ridgemont High (and a couple of other movies about the state of teenage existence release the same month)

Previously:

Porky’s (March 1982)

Body Heat (August 1981)

Stripes (June 1981)

Heaven's Gate (April 1981)

Cutter’s Way (March 1981)

9 to 5 (December 1980)

Ordinary People (September 1980)

Urban Cowboy (June 1980)

Little Darlings (March 1980)

I saw Poltergeist when it first aired on network TV. For those who weren’t around in the early 80s, there weren’t a lot of ways to see a movie if you missed its run in the theater. Poltergeist didn’t predate VCRs, but it DID predate Blockbuster and even the small rental stores. But the biggest movies often had a showing on television. Edited for content and with regular commercials, but still.

Anyway, the premiere of Poltergeist on TV was a big deal. I begged my mom to let me go see it at my friend Mark’s house down the block. His whole family was going to watch it. Against her deep misgivings - she thought I’d be terrified of it - she let me.

When I got back - it was early, the movie aired in the afternoon - my mother was prepping dinner. I remember her tight lips when she asked me what I thought of the movie. I said it was fine. She said good and told me to go upstairs and shower before dinner.

I completely fell apart. I couldn’t go upstairs alone. I was terrified, all of a sudden and all at once. The movie was horrifying and it’s scariest scene took place in the room I had, until then, felt safest in - the room where I sat on the floor and played with my Legos while my mom chatted on the phone or made me a snack.

I was a nightmare to my parents. I wouldn’t go upstairs alone, I wouldn’t go downstairs alone, I wouldn’t play in my playroom without someone next to me because I was worried a tree was going to attack me through the window. I cried. I couldn’t sleep. Weeks went by. I honestly didn’t get any better until the summer ended and I went back to college. BAM!

This writeup captures a lot of what I like about Poltergeist: the fleshed out details. A lot of movies, especially horror movies, skimp on this because it's more fun to jump right to the walls bleeding. I always liked how Williams's mom character finds it all fun and interesting at first. I'd never caught the teen mom implication, which maybe helps explain why she's so excited by something strange and new and different.

Also, I'm not gonna say that the sequels are up to this level or even, frankly, good, but I AM gonna say that I like Poltergeist 2 a whole lot and that Cane is an excellent horror movie villain.