The Prime of Roger Corman

In the busy years of 1962 and 1963, the late B-movie king made a statement that failed and a transcendent science fiction film. Both captured a filmmaker working at top form.

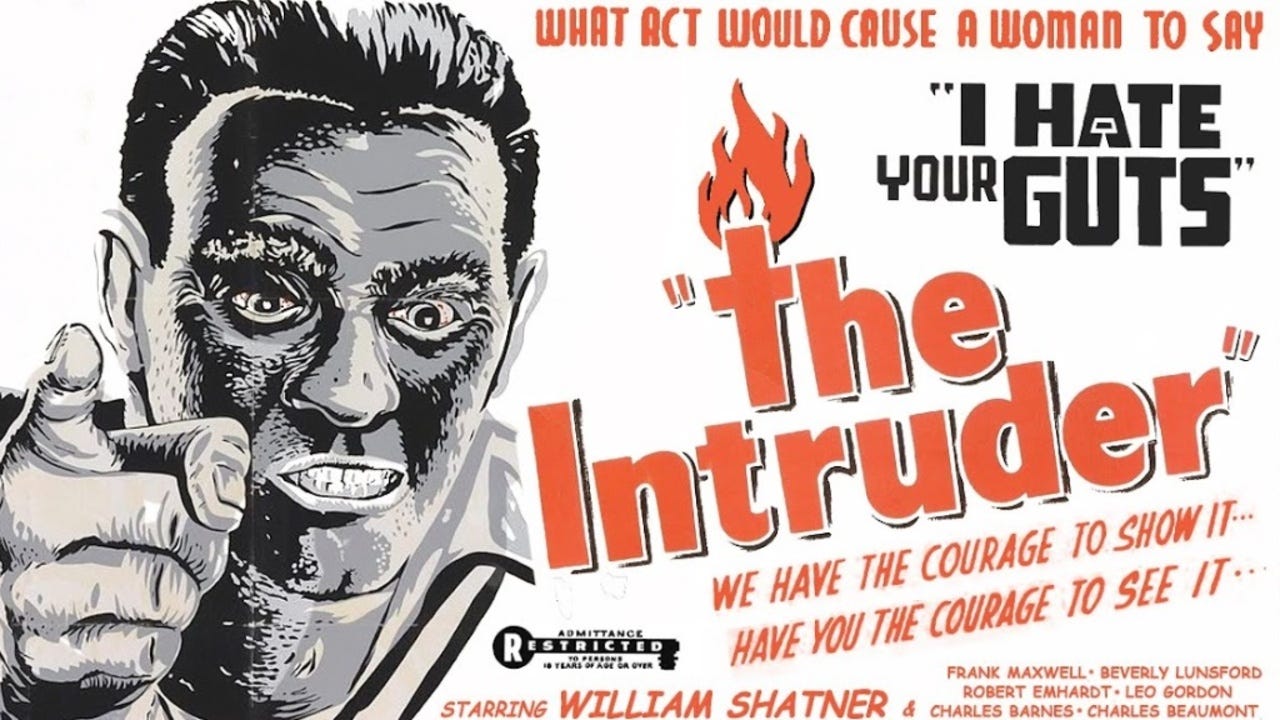

Read enough interviews with Roger Corman and you’ll find a few details come up again and again. He had success because he worked cheap. He liked to scout for up-and-coming but unproven talent. (These two details are not unrelated.) He truly did shoot a movie in two-and-a-half days. His enthusiasm for his Edgar Allan Poe adaptations and trailblazing ’60s counterculture films remained undimmed. Genial and reflective, Corman would always happily talk about whatever the interviewer, quite often a lifelong fan, would want to discuss and even in his later years seemed to have total recall of each production. Yet he rarely missed a chance to talk about the 1962 film The Intruder (variously retitled Shame, The Stranger, and I Hate Your Guts), which he would describe as the only film that lost him money. But that didn’t make it a failure.

In 1962, Corman was working at a breathtaking pace, and with considerable success. In addition to The Intruder, that year saw the release of The Premature Burial, Tales of Terror (both part of his Poe cycle), and Tower of London. Corman, working with hisworking his producer/brother Gene Corman, was able to pull this off via ten-, sometimes fifteen-day shooting schedules, a budget-consciousschedules a budget-conscious approach that extended to every aspect of the production. But it was Corman’s skill as a director that made them work. The budget came first but substance hardly came last.

Nor did politics. Part of Corman’s success as a director and producer (apart from one film, he segued purely into the latter role in 1970) came from understanding changing tastes, be it appealing to an underserved teen audience in the ‘50s and ‘60s or the desire for graphic violence and nudity in the ‘1970s. But he also realized that genre films, whatever their requirements, left a lot of room for other stuff. Jonathan Demme once defined Corman’s formula (in an interview with Corman himself) as "a good degree of sex, some violence, a bit of nudity, and perhaps a subtle social statement.” Check off the boxes you need to check and you’re left with a lot of blanks to fill in yourself.

But once, and only once, Corman threw away his own rules. The Intruder adapts a novel by Charles Beaumont, a frequent Twilight Zone writer who scripted the film himself. “I read the book […] and thought this is an excellent idea for a picture, and it fit my political beliefs” Corman told Chris Nashawaty in the laetter’s career-spanning 2013 oral history Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses: Roger Corman: King of the B Movies. Specifically, Beaumont’s novel dealt with school integration in Caxton, a small town in the American south, and the forces trying to stop it.

As the film opens, the white citizens of Caxton have largely resigned themselves to the inevitability of court-ordered school integration. They might not like it, but that’s the law. But that attitude changes with the arrival of Adam Cramer (William Shatner), a Washington D.C. outsider from the Patrick Henry Society (a thinly veiled John Birch Society stand-in). Disembarking from a bus with a smirk on his face, Cramer immediately begins trying to find the weak points of the town’s resolve to remain law-abiding. He doesn’t have to look very far, almost immediately hearing a music-to-his-ears racial epithet when checking into his hotel. But it’s when Cramer hooks up with the wealthy landowner Verne Shipman (Robert Emhardt), he finds a patron for his agitation, which threatens to take a violent turn.

Though The Intruder finds the director playing it straight, it’s also unmistakably a Corman film. Shooting on location in small-town Missouri provides budget-conscious production value, but Corman also fills the film with B-movie flourishes, like a restless camera dolly that turns into a match cut on Shatner’s eyes that takes the film from one location to another. The Intruder also brings B-movie bluntness to its central topic. Made at a moment when few films directly addressed the American racism and inequality, The Intruder gives the subject a gloves-off treatment, loadingfilling the script with racist invective and giving Cramer a speech in which he justifies his audience’s prejudice by tying integration to a plot conceived by Jews and communists. (This is undoubtedly one of Shatner’s greatest performances, directing the same smarmy charisma that defined Star Trek’s Captain Kirk to sinister ends.)

The Intruder is raw but effective, never shying away from its daring premise. It suggests an alternate future thatin which it would have marked the moment Corman became a proper and serious filmmaker, one willing to take on issues of the day that others would not touch. A few years later, The Trip and The Wild Angels would deal frankly (in exploitation movie-friendly terms) with psychedelic drugs and bike culture, respectively. But a successful run of The Intruder could have found the director tackling even more politically charged issues. Corman believed in The Intruder project so much that he mortgaged his house to make it, which might explain why he was reluctant to make another such attempt. It’s also why it’s little wonder the film’s failure would still be on his mind years later, though he quickly bounced back professionally. And creatively.

The next year would be even more productive. Five Corman-directed films would arrive in theaters: The Young Racers, The Raven, The Terror (a notoriously cheap quickie made with Jack Nicholson and Boris Karloff on sets left over from The Raven),, The Haunted Palace, and X: The Man with X-Ray Eyes. Corman was particularly proud of this last one. In 2017, I had the pleasure of attending the first Overlook Film Festival, where Corman served as a guest of honor and participated in a post-screening Q&A of the film of his choice. He chose X: The Man with X-Ray Eyes.

It’s not hard to see why. Scripted by Ray Russell and Robert Dillon, X works brilliantly as a fast-paced B-movie exploring a hooky premise within a brisk 80-minuted running time. Ray Milland stars as Dr. James Xavier, an ambitious medical researcher convinced that, with the right formula, the human eye can be altered to see beyond the spectrum usually available to it.

He’s so convinced, in fact, he tests the formula on himself. Success! Soon he can diagnose patients by peering beneath their skin. And, as a bonus, he can see through clothing, as he discovers at a swinging cocktail party that makes great use of exotica giant Les Baxter’s score and some careful framing so the nudity remains out of frame. (This is a 1962 Corman production, not one from 1972.) But there'sthere’e a problem: Xavier can’t turn it off. And after accidentally killing a colleague, he flees for a life as a fugitive.

X delivers all the goods expected of a sci-fi horror film designed to play drive-ins, then it goes further. (Check the boxes then fill in the blanks.) The film’s horror is both physical and cosmic. Milland plays Xavier as a man in tremendous pain—in some respects, the role isit’s not far removed from his Oscar-winning turn as a bottoming-out alcoholoic in The Lost Weekend—but his self-inflicted curse also radically alters his personality. Adrift, Xavier finds work first as a sideshow attraction (royally pissing off a skeptical customer played by Corman regular Dick Miller) then a healer in the employ of a sleazy character played by Don Rickles. Working in both capacities, he seems like a hollowed-out man doomed to live on the fringes of a life he once enjoyed, as he desperately tries to reverse his altered state.

Instead it just gets worse, and in the film’s extraordinary final stretch, Xavier stumbles into a tent revival meeting and seems to see into the dark heart of the universe itself. The seemingly Lovecraftian realization revelation pushes him into madness and leads him to pluck out his own eyes. Roll credits. It’s an ending made semi-famous by Stephen King’s 1981 non-fiction horror reflection Danse Macabre, in which King suggests an even better ending would be to have Xavier exclaim “I can still see!” after blinding himself (or at least attempting to). I don’t know that I agree (it feels like a hat on a hat), but Corman seemed to when he brought it up to the Overlook crowd, even saying he wished he’d thought of it.

Yet X:The Man With X-Ray Eyes doesn’t need that extra nudge to be unforgettable. What begins as an irresistible “What if?” evolves into a tour of America’s sleazy underside, complete with a stop in Las Vegas that goes awry. But they’re all just pit stops as the film makes its way toward an existential abyss. Like the best B-movies, it understands how much can be smuggled into a movie provided it supplies the requisite thrills and chills. The Intruder could have established Roger Corman as an artist. Instead, films like X: The Man with X-Ray Eyes proved he’d been one all along.

I'm a graduate of the Roger Corman Film School. I wrote a movie Roger pitched to me as "I have this house set, and we can turn it into an underground lab. We'll call it The Terror Within. I want it post-apocalypse and I'm tired of nuclear war. Do you have any ideas?" And that little "programmer," written between drafts of the script Roger and I and everyone else who read it just knew would be a "hit", became Roger's biggest hit of the late period - even getting solid reviews for the "underlying pro-choice message of the film" - and still stands up 36 years later (while the "hit" became the biggest flop of that period, proving that William Goldman definitely knew what he was talking about when he described the three rules of Hollywood). I am glad to see people finally recognizing Roger for the genius he was. Knowing him and working for him was the best part of my time in Hollywood.

My notes when I watched The Intruder a couple of years ago: "Corman just going for it without any couching or metaphor or subtext, and some serious wildcat filmmaking. Shatner is much more like an evil Kirk here than in either of the "evil Kirk" episodes of Star Trek. Ending seems quaintly pat now."