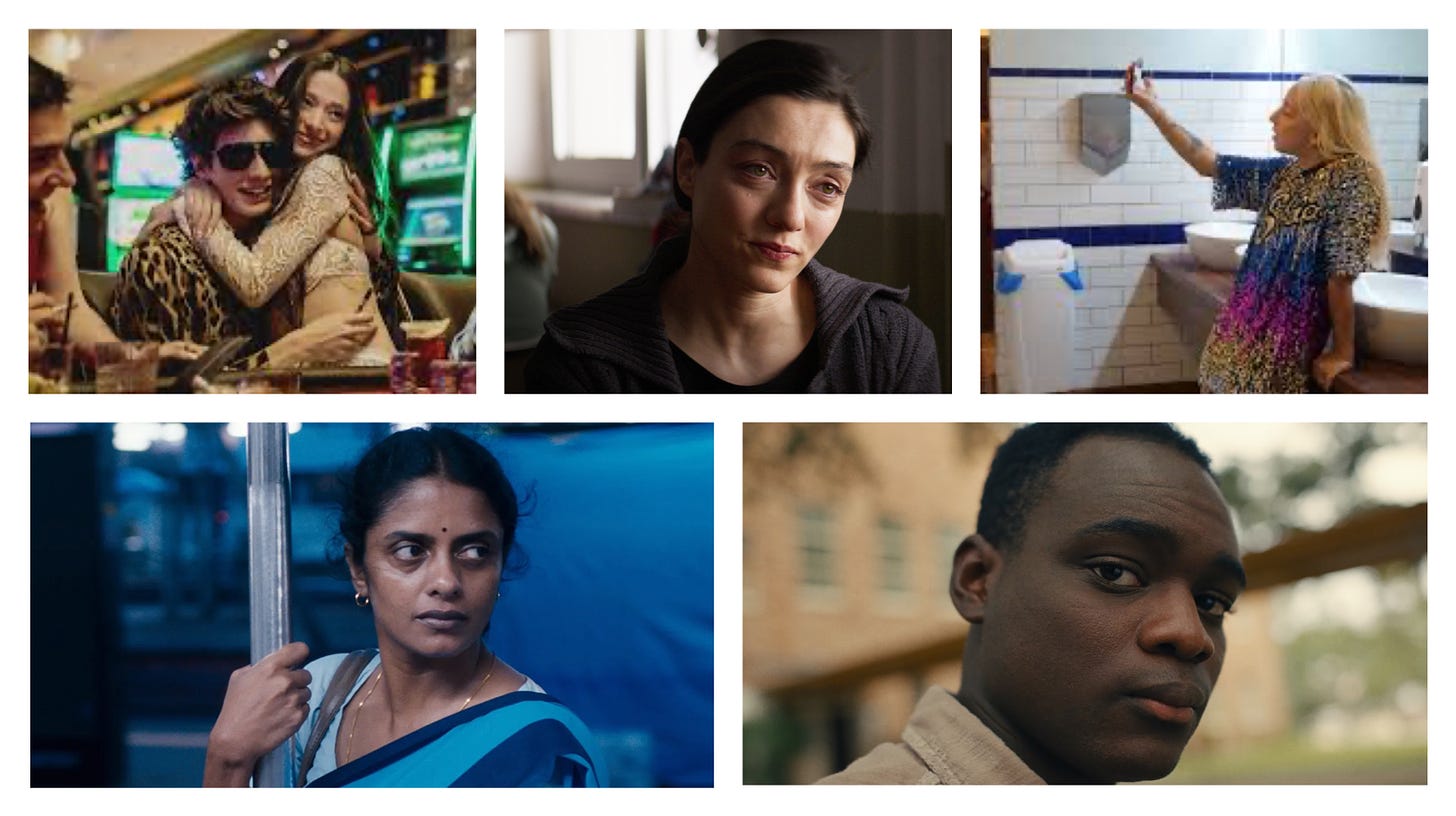

The Best Films of 2024 (Scott's List)

There were many, many, many great films in 2024. Just don't look to Hollywood for any of them.

When Keith and I were discussing our best-of lists toward the end of 2024—his closed our calendar year two days ago, mine kicks off 2025—the sheer volume of great movies I’d seen had me very excited, but I was at a loss about what belonged at the top. That’s not to say that my #1 isn’t the instant classic I believe it to be, but the sheer parity of excellent films in 2024 seemed notable, almost to the point where I could reorder my Top 15 (and some of the Honorable Mentions) and feel satisfied about how the list looked overall. And I’m choosing to be enthusiastic about the fact that virtually none of the films were coming from Hollywood studios, which are less and less interested in producing serious, original work, even for the sake of statuettes—or at least a little institutional dignity. It was confirmation that the rest of the world, including American independent filmmakers, didn’t need that big gravitational force to stay in orbit.

Before getting to the list, I wanted to give a special mention to two entries, Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig and Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World, for incorporating real-world events into their narratives. We’re about to enter a dark chapter in American life—or let’s say “uncertain,” if you want to be euphemistic about it—and it’s my fervent wish that filmmakers and other artists keep the lens open to history as it unfolds, rather than waiting for someone else to reflect on it decades from now. We shouldn’t have to rely on a Romanian to give us the most vivid picture of what it’s like to live in contemporary America. Let’s hope for a 21st century Medium Cool.

The Top 15

15. Between the Temples (dir. Nathan Silver)

Words like “rumpled” and “untidy” define Ben Gottlieb (Jason Schwartzman), a middle-aged widower trying fecklessly to stabilize his life, which currently involves living with his two mothers and serving as a cantor who’s literally and figuratively lost his voice. Those words also define Between the Temples, a deliberated jagged comedy that lives for uncomfortable moments, many of them involving Ben’s relationship with a former voice teacher (a perfect Carol Kane) who wants him to coach her for a belated bat mitzvah. Their relationship lurches into typically messy seriocomic territory but it always feels authentic and earned, right alongside the contributions of a supporting cast that’s lively around the margins.

14. Hit Man (dir. Richard Linklater)

I’m not going to use this space to complain about a sexy, hilarious crowd-pleaser with an A-list star and a big-time director getting chucked into the Netflix content mill. (Oh dammit, too late!) But Richard Linklater’s delightful embellishment of a true story serves as a companion piece of sorts to his 2011 dark comedy Bernie, both films based on stranger-than-fiction Skip Hollandsworth features for Texas Monthly and serving as vehicles tailored to the abundant talents of their leading men. In this case, Glen Powell’s boundless charisma springs from the humble roots of a taciturn college professor who comes alive when he steps into the role of an undercover officer who snares people trying to hire him as a contract killer. Adria Arjona is pure flames emoji as a woman he talks out of trouble, only to land himself in a heap of it.

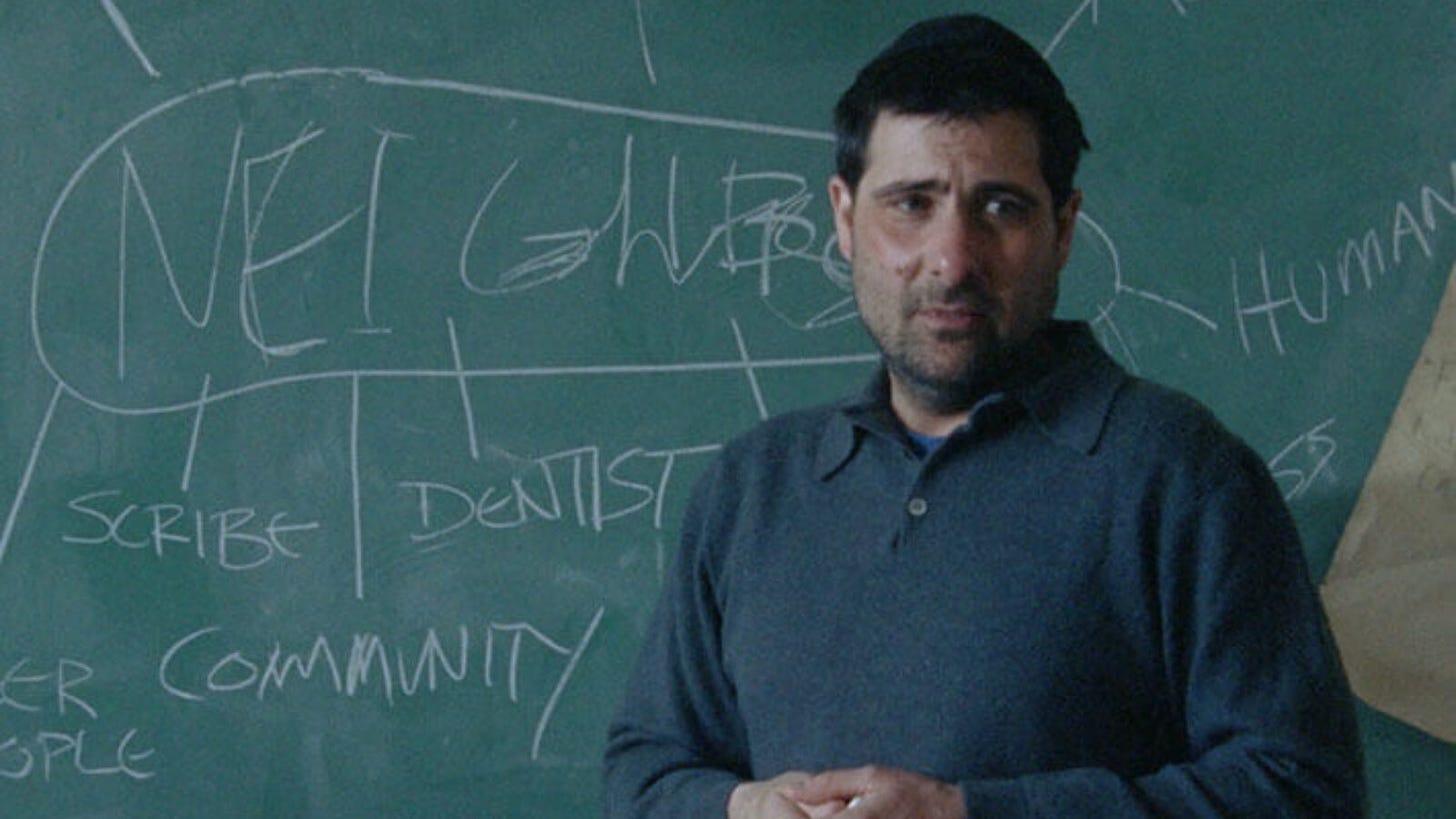

13. The Brutalist (dir. Brady Corbet)

Brady Corbet’s heroically ambitious swing for the fences—a 215-minute epic shot in VistaVision, a format that hadn’t been used since One-Eyed Jacks in 1961—would have landed much higher on my list had it not stumbled in the closing stretch, when the tense collaboration between a Jewish architect (Adrien Brody) and his wealthy, impulsive client (Guy Pearce) takes Corbet’s statement on art and commerce to a too-literal extreme. But The Brutalist is riveting most of the way, with the architect’s construction of a massive community project taking on significance akin to the bell in Andrei Rublev. Only in Corbet’s America, the will of an uncompromising artist is always subject to the fickle impulses of the man holding the purse.

12. Good One (dir. India Donaldson)

India Donaldson’s debut feature would do well on a double-bill with Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, both small-scale and keenly observed dramas about a hiking trip that reveals the hairline cracks in a relationship. The “good one” here is Sam (Lily Collias), a teenager who agrees to come along on a camping adventure with her father (James Le Gros) and his recently divorced friend (Danny McCarthy) but is now at an age where she can see their flaws more clearly. The film boils down to a single, subtle moment where the friend says something half-jokingly (or not) to Sam that unsettles her and subsequently shows the limits of her father’s understanding and support. If you’re looking for hope in American indies, Good One is as audaciously minor as The Brutalist is audaciously outsized.

11. The Seed of the Sacred Fig (dir. Mohammad Rasoulof)

For as long as Iran has been among the great gardens of international cinema, directors have had to work around government censors who not only limit their expression, but often threaten their freedom. Before The Seed of the Sacred Fig premiered at Cannes, director Mohammad Rasoulof fled the country for Germany to escape an eight-year prison sentence for making the film, and it’s abundantly clear why when you see this extraordinary shot to the bow. There may not be a great deal of subtlety to the story of a principled lawyer (Missagh Zareh) who’s compromised by his promotion to an investigating judge for the Revolutionary Guard in a period of cultural tumult. But as he continues to rubber-stamp death sentences for protesters and his own daughters start to revolt, the film gets caught up in nerve-wracking tension and paranoia—all with the Iranian government as the clear foe.

10. All We Imagine as Light (dir. Payal Kapadia)

Through a quiet accumulation of beautiful moments—starting with the introduction of its heroine as a face-in-the-crowd in Mumbai, a city of many faces and backgrounds—Payal Kapadia’s drama details the lives of three nurses who bump up against the limitations of a place that demands a can-do “spirit,” but tests women and immigrants with onerous restrictions. Yet All We Imagine as Light is only incidentally a polemic, because it’s so focused on small gestures or social mores that have a big impact on its characters’ lives. When the action moves in the second half from the hustle-bustle of the big city to a village near the water, the tonal shift is so exhilaratingly vivid that you can almost taste the salt in the air.

9. Evil Does Not Exist (dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Who could have guessed that one of the most enthralling scenes of the year would be a community meeting over the location of septic tanks in a proposed “glamping” site in an idyllic Japanese mountain village? And yet, here we are. In Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s wildly eclectic follow-up to Drive My Car, the meeting results in two PR reps from Tokyo getting introduced to a local “odd job” man (Hitoshi Omika) who may be able to help them with the project, but their effect on each other’s lives plays out in ways that cannot be anticipated. Though the story suggests something like Local Hero, with the would-be urban conquerors swayed by their rural hosts, Hamaguchi steers the material in a much more experimental direction, including a brilliant conversation-starter of an ending. Eiko Ishibashi’s score is one of the year’s best, too.

8. The Substance (dir. Coralie Fargeat)

With her follow-up to Revenge, a bracing, nasty feminist twist on the rape-revenge horror film, French director Coralie Fargeat once again leaves nothing in the tank, uncorking a black comedy on celebrity and vanity that evokes Carrie, David Cronenberg, and the aerobics fanaticism of the 1980s. The absence of vanity from Demi Moore, one of the most glamorous stars of that decade, is remarkable in itself, as she plays a popular TV fitness show host who turns to a synthetic fountain of youth after she hits 50 and her grotesque boss (Dennis Quaid) turns her in for a better model. That the model turns out to be a clone of sorts, played by a perky Margaret Qualley, takes The Substance to another level entirely, as internalized misogyny puts her at war with herself. None of this is subtle, all of it is dazzling.

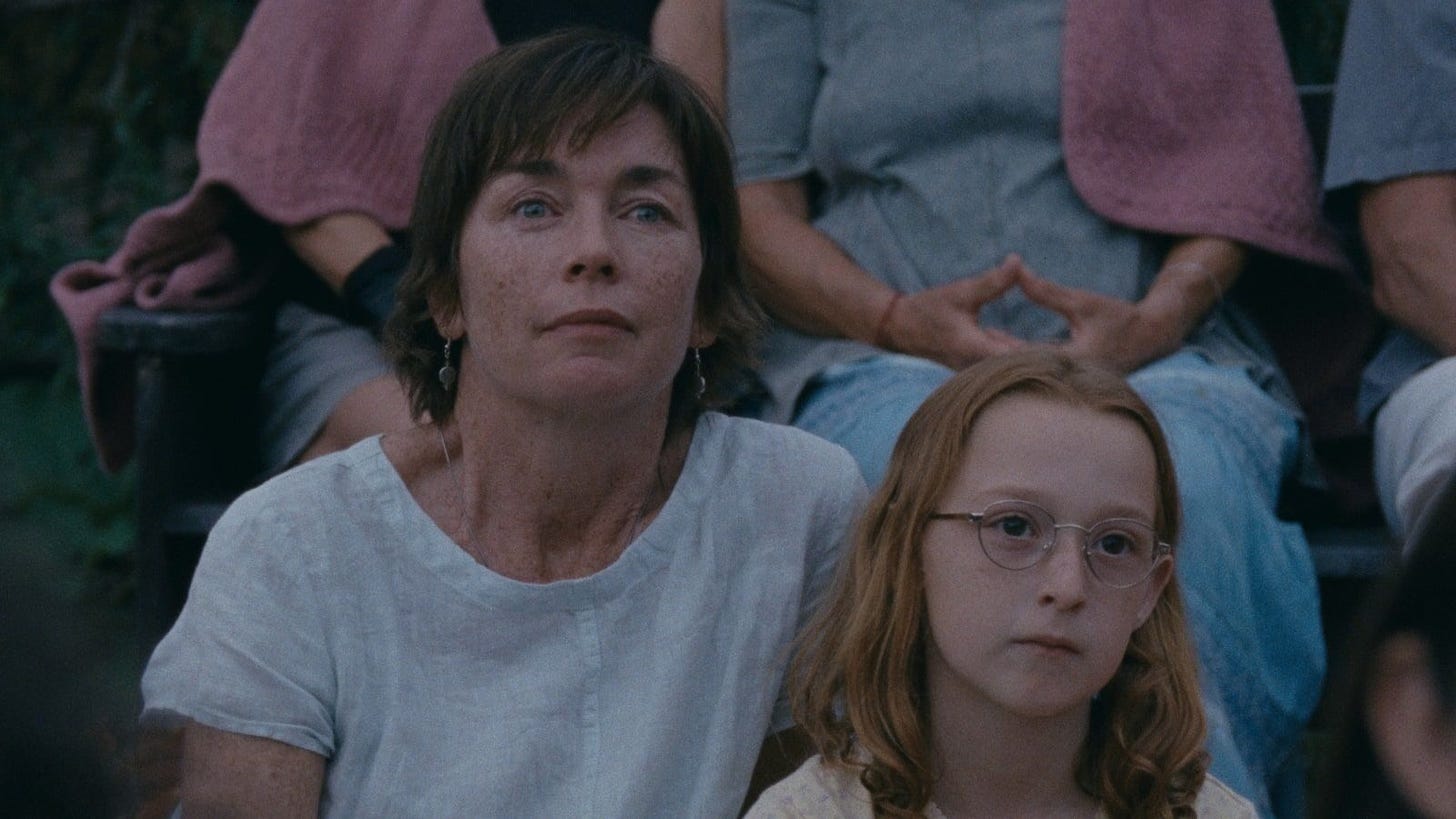

7. Janet Planet (dir. Annie Baker)

Playwright Annie Baker’s debut as writer-director chronicles the relationship between Janet (Julianne Nicholson), a single hippie-ish acupuncturist, and Lacy (Zoe Ziegler), her shy, awkward 11-year-old daughter (Zoe Ziegler) with humor and great attention to detail, particularly in its evocation of the duo’s home in rural Massachusetts in the early ‘90s. Divided into three sections, each named for a lover or roommate that Janet impulsively brings into their lives, Janet Planet jabs amusingly at their touchy-feely progressive environment, but it’s also incisive in grappling with the co-dependence of mother and daughter, who need to negotiate a healthier relationship. Small indie films don’t often get described as “immersive,” but Baker’s meticulous control over every aspect of the production makes it feel like a film you enter into as much as watch.

6. Nickel Boys (dir. RaMell Ross)

One of the most exciting aspects of Nickel Boys is that if you’ve seen Hale County This Morning, This Evening—a non-linear, impressionistic 2018 documentary about the lives of Black inhabitants of the title county in Alabama—then you’ll quickly recognize this Colson Whitehead adaptation as the work of the same director, despite being set in a different time and place and shot in a radical first-person style. Director RaMell Ross has just that strong an eye. It takes a little while to get used to the camera technique, but the artful framing achieves a disturbing intimacy, locking us (at least at first) into the perspective of a promising Black student in the Jim Crow era whose dreams are cruelly waylaid by a stint in an abusive Tallahassee “reform school.”

5. About Dry Grasses (dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

Splitting the difference between the psychological acuity of early films like Distant and Climates with the sprawl and regional allure of later work like Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Ceylan’s latest concerns Samet (Deniz Celiloğlu), a middle-school art teacher who’s desperate to wind down his requisite stint in a snowy Anatolian backwater so he can make way back to the city. But his plans are complicated first by an inappropriate gift to his favorite student and then later by his infatuation with Nuray (Merve Dizdar), a teacher from another village who’s as idealistic as he is cynical. The two separate subplots eventually add up to a richer whole, one that exposes the limits of Samet’s worldview and the hidden consequences of his actions. And the film creates a winter landscape of harsh, Fargo-esque beauty. But it’s Dizdar’s Cannes-winning performance—more on that below—that makes About Dry Grasses truly special.

4. Red Rooms (dir. Pascal Plante)

It seems fitting that a movie with “rooms” in the title has taken up more space in my head than any other film in 2024, because I don’t know that I’ve seen anything that so powerfully conveys the way the darkest corners of cyberspace can stoke paranoia and obsession, or trigger behaviors that we commonly describe as “Extremely Online.” In this Fincherian French-Canadian drama, Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy) is an inscrutable model who wakes up early every morning to get public seating for a high-profile trial involving a man accused of torturing and killing women for the edification of dark-web bidders. Her unlikely friendship with an out-of-towner (Laurie Babin) convinced of the man’s innocence provides a fascinating study in contrasts and a hard lesson in how different people process information. In other words, this is “I did my own research” in shocking extremis.

3. Close Your Eyes (dir. Victor Erice)

Premium “old man cinema” from Erice, who miraculously returns from a three-decade absence to remind us that the same man who directed The Spirit of the Beehive a half-century earlier hadn’t lost his touch. Close Your Eyes is a movie about the movies, starting with a long sequence from the unfinished production in which the lead actor simply walked off, leaving the film’s director, Miguel (Manolo Solo), without his collaborator and short-circuiting his career. When a Spanish TV show in the vein of Unsolved Mysteries attempts to revisit the incident, it unlocks something within Miguel that’s plainly analogous to Erice, whose own absence from filmmaking has been conspicuous. Yet Close Your Eyes moves like a dream, with sentimental nods to cinema itself that never get too sticky, because a sense of grief and loss are ever-present.

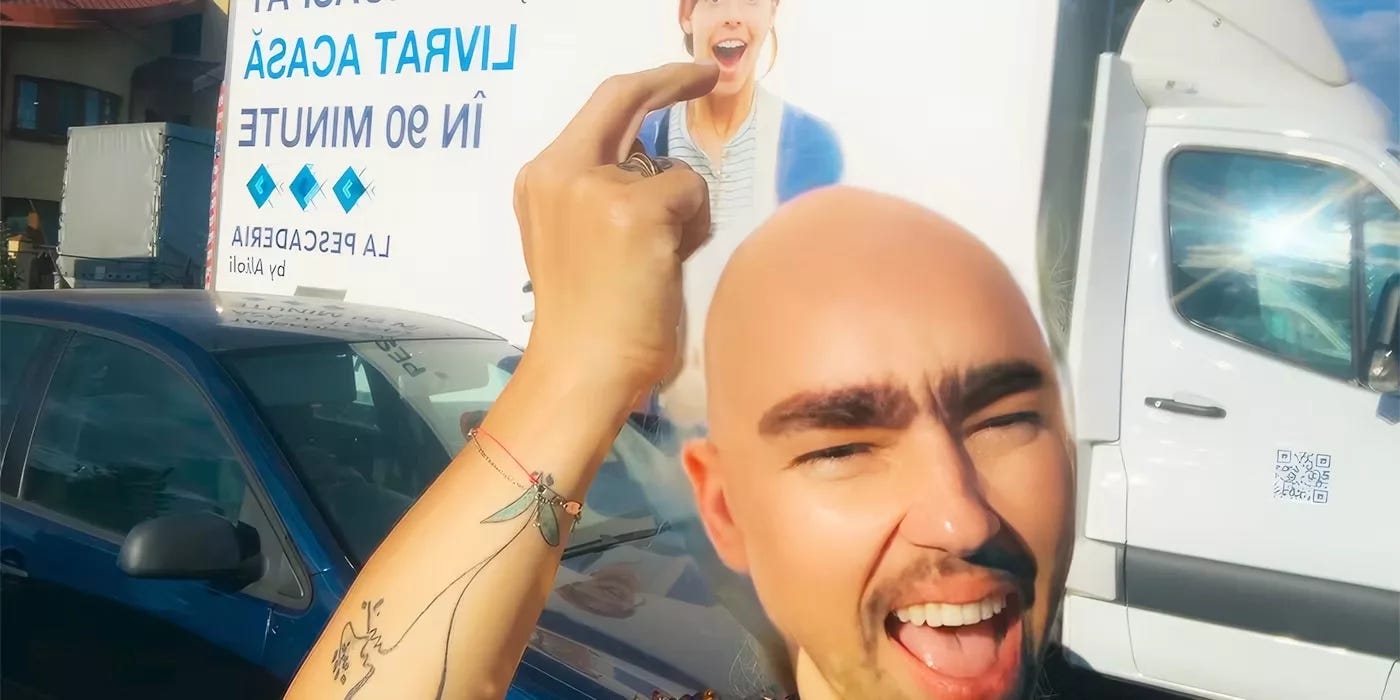

2. Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (dir. Radu Jude)

Nearly three years ago, I wrote about how Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, a COVID-era provocation from Romanian director Radu Jude, was the best film about life in America at the time, even though it was set in contemporary Bucharest. And now Jude’s follow-up has accomplished exactly the same thing, confirming his genius for turning the up-to-the-minute horror and absurdities of modern life into dark and often bawdy political comedies. Where his heroine in Bad Luck Banging was a teacher on the defensive after a homemade porn tape with her husband inadvertently leaked online, Angela (Ilinca Manolache) in Do Not Expect is irreverent by nature, taking time from her thankless job as a production gofer to record videos as “Bobita,” an alpha-male type persona of the Andrew Tate variety. It’s somehow unsurprising (if hilarious) for Uwe Boll to make an appearance here as himself, but Jude’s essayistic style allows him to shift gears to more sober material, too.

1. Anora (dir. Sean Baker)

In a year without an obvious number-one-with-a-bullet, I picked the one that had me floating out of the theater like a cartoon character drifting toward a pie on a windowsill. Baker’s longstanding interest in sex workers—and in treating sex work as work, however much such intimacies might complicate people’s lives—leads to this inspired upending of the Pretty Woman fantasy of a humble stripper (Mikey Madison) courted by a rich client, in this case the hard-partying son of a Russian oligarch. Naturally, the client’s parents want their quickie Vegas marriage annulled, but our heroine defends herself righteously, viciously, and hilariously, if perhaps quixotically. There are stretches of Anora that feel like Billy Wilder or Ernst Lubitsch by way of John Cassavetes, but then Baker hits you with moments of real tenderness and a keen delineation of social class.

Honorable Mention (no particular order): Nosferatu, Blitz, Juror #2, A Real Pain, Girls Will Be Girls, Last Summer, Green Border, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, The Beast, Love Lies Bleeding, How to Have Sex, Daughters.

Performance of the Year: Merve Dizdar, About Dry Grasses.

It takes a while for Dizdar to turn up in About Dry Grasses, which spends a significant early chunk of its 197 minutes detailing the miserable life of Samet (Deniz Celiloğlu), a middle-school art teacher desperate to run out the clock in snowy Anatolia and return to a more cosmopolitan lifestyle in the city. But when she does appear as Nuray, a more idealistic teacher from a nearby village who draws romantic interest from Samet and his roommate, Dizdar’s presence elevates the film significantly. As an activist who lost her leg in a terrorist explosion, Nuray naturally casts Samet’s cynicism in an uncharitable light, but the depth of her intelligence and emotion, on fullest display in a long dinner conversation at her place, is awe-inspiring to witness.

Scene of the Year: Staged interrogation, Hit Man

In Richard Linklater’s wonderful fact-embellished comedy, Glen Powell stars as Gary Johnson, a college professor who moonlights as a fake contract killer to ensnare those who request their services. But he falls hard for Madison (Adria Arjona), who he talks out of killing her abusive husband and talks into a relationship that’s sexy and more than a little dangerous, given her murderous intentions. Late in the film, when the husband is shot and suspicion turns to Madison over a million-dollar insurance policy, Gary is tasked with wearing a wire to interrogate her, but he again tries to spare her by giving her written cues on his cell phone. The result is like a movie within a movie, with Gary directing Madison through a scene and the two actors vibing off each other with the irresistible chemistry that makes Hit Man such a blast.

Reason for Hope: Movies outside of Hollywood.

If the quality of the films coming out of major studios is your bellwether for the quality of a movie year overall, then you’re going to make yourself increasingly miserable. The best studio movies this year were by elderly directors like George Miller (Furiosa) and Clint Eastwood (Juror #2) who’d been grandfathered into a system that looks to be putting them out to pasture. Yet the sheer abundance of great films in 2024 made it clear that the medium can do just fine without them, so long as global hot spots keep producing and American independent circles can turn out work as diverse as Anora, The Brutalist, Nickel Boys, Good One, Janet Planet, and Between the Temples. Art finds a way.

Reason for Despair: Streaming austerity.

The trick of Big Tech disruptors is to spend (and lose) massive amounts of money up front to attract a client base while undercutting an existing model, then turn much less generous (and yet more expensive) when the old model has been replaced. And so the glory days of cord-cutting while Netflix, HBO Max, Apple TV+, and other platforms scoop up talent and bankroll expensive dream projects have dried up and now the pickings are so conspicuously thin that Juror #2, a rock-solid courtroom drama by an aging master, has been quietly shuttled to streaming and labeled a “Max Original.” These platforms may still have to compete with each other for subscription dollars, but the days of profligate spending are over—that is, unless you’re talking about your monthly bills.

Special Effect: The phone filter in Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World.

As Angela (Ilinca Manolache) drearily zips around Bucharest in her car, filming casting videos for a piece of workplace propaganda, she blows off steam by recording TikTok videos as “Bobita,” a profane misogynist that parodies Andrew Tate and other influencers in the manosphere. A perfectly lovely young woman, Angela disguises her identity by activating a filter that turns her into a bald-headed man with a thick unibrow and a deep voice—a persona Manolache had honed before shooting. Sometimes great special effects bust the budget and sometimes they’re just sitting there on your new phone.

Most Anticipated: The Battle of Baktan Cross.

A new Paul Thomas Anderson project is always something to circle on the calendar and this one is starting to take shape as an expensive Warner Brothers production—so much for that Reason to Despair!—starring Leonardo DiCaprio and currently slated to be released in IMAX this summer. It may or may not be loosely inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, and the rest of the cast includes Sean Penn, Regina Hall, Benecio del Toro and Alana Haim, who’d been so terrific in Anderson’s last film, Licorice Pizza. Bottom line: The man is nine for nine. For such a risk-taker, he’s proven to be a sure bet.

I haven’t seen any of Victor Erice’s work, but am now very curious about CLOSE YOUR EYES. Would it benefit to watch his other films before diving into this?

I wish Red Rooms had gotten more attention. What made it my favorite of the year was all the subtle clues to why Kelly-Anne behaves the way she does: her darkweb handle is Lady of Shalott, a reference to a poem about the dangers of isolation. Don't think it's a coincidence that her best friend is a robot.