The Best Films of the Year So Far (* According to Metacritic, According to Me): Part 1

Catching up with the most acclaimed films of the past eight months.

This time last year, when we launched this newsletter, I made a confession: I’d been a bad cinephile, at least through the first half of 2021, having missed many of the films that critics had considered the best of the year to date. To catch up with the broad consensus, I turned to Metacritic and its list of the year's highest-rated films, calculated from aggregated reviews.. (Standard disclaimer: Many of the actual best films of the year tend to be polarizing, and thus don’t have Metacritic or Rotten Tomatoes scores that would make them eligible for a project like this.) This year, working on The Reveal has made me a slightly better cinephile, but I know there are still huge gaps in my viewing, particularly with off-the-radar independent and foreign films from unestablished directors.

So, once again, I looked at Metacritic’s list of the best films of the year so far. And, once again, I discovered I’d seen very few of them—and got to work rectifying that. Just like last summer, I’m counting them down from 10 to 1 (10-6 today, 5-1 next week), based on their Metacritic scores, to determine whether I find them truly “list-worthy”—or the uninspired beneficiary of critical consensus, ho-hum movies everyone seems to agree is pretty good. There are some titles on here that I’ve opted to skip, either because they’re filed as 2021 films (The Worst Person in the World), have yet to be released (Decision to Leave, Moonage Daydream), or were not available for me to watch (A Night of Knowing Nothing).

One more note: We are currently in the dog days of summer, before many of the Cannes favorites have debuted in theaters and before the start of the festival season that will bring us quality work from Venice, Toronto, New York, and other year-end launch pads. The Metacritic “best of” list will shift dramatically in the coming months, and my own sense of 2022 will surely shift in kind, so I tend to be conservative in predicting which of these films (if any) will wind up in my final Top 10. But there will be plenty worth seeing in this feature, so let’s get to them:

10. The Territory (dir. Alex Pritz)

Current ranking/score: #14, 84.

How to watch: In theaters.

List-worthy?: No.

Premise: The indigenous peoples of the Brazil have long been threatened by deforestation, and Alex Pritz’s documentary, produced by Darren Aronofsky, follows just such a conflict between Brazilian farmers and the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, who are trying to keep their protected lands (and culture) from seizure.

Sample praise: “To see the villagers take matters into their own hands, capturing proof of the encroachment on their land that the government chooses to ignore, is a special kind of thrill.” — Claire Shaffer, The New York Times

Thoughts: The encroachment of “civilization” on the untouched indigenous cultures of this last frontier has inspired movies many times before, most recently the risible Eli Roth exploitation film The Green Inferno, which imagined a tribe having their way with college environmentalists. The Territory is a much more responsible treatment of a real-life conflict, but it does have the conspicuous slickness of a National Geographic production. Pritz gives a lot of latitude to two subjects who represent different generations: Neidinha Bandeira, a veteran activist who has received death threats for her work on behalf of indigenous people, and Bitaté, a young Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau leader who uses modern tools, like drone cameras, to present evidence of farmers illegally seizing protected land. It’s a unique collaboration between filmmaker and subject, because the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau need outside advocacy, but are naturally wary of any outsiders, even sympathetic ones like Pritz, setting foot on their terrain. Pritz entertains the other side of the issue, too, which isn’t the simple case of greed and villainy you might assume, though when Bitaté talks about farmers wanting his people simply to “disappear,” he’s not far off. When people consider land as something to be used, not lived in, human tragedy often follows.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

9. Happening (dir. Audrey Diwan)

Current ranking/score: #12, 86.

How to watch: AMC+, rental.

List-worthy?: On the fence, leaning yes.

Premise: In 1963 France, a promising young literature student named Anne (Anamaria Vartolomei) gets pregnant, a development that threatens to short-circuit her ambitions as a writer and scholar. At a time when abortion is illegal, Anne goes to desperate and dangerous lengths to terminate the pregnancy and reclaim her life.

Sample praise: “When I first saw the movie, it felt like a warning shot from a still-distant land. Now it feels urgently of the moment.” — Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

Thoughts: As that Dargis quote suggests, Happening has a special resonance after the Dobbs decision wiped out a federally protected freedom that has been guaranteed for American women for half a century. Of particular resonance are the criminal penalties not just for abortion seekers and providers, but anyone who aids a woman for trying to procure one. Much like the great Romanian film 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, Happening does a brilliant job of immersing us in the air of paranoia that naturally rises when someone like Anne has to decide who to trust with her secret and what options she has—even some that might cost her life. The commonalities shared by abortion narratives like Happening and 4 Months and Never Rarely Sometimes Always despite differences in milieu speaks to the dreadful universality of the issue. What gives Diwan’s film its distinction is candor, a willingness to show in sometimes graphic (though never distasteful) detail what it’s like for Anne to try to end her pregnancy on her own or risk the interventions of others. The France of 1963 has now come to America 60 years later.

8. Playground (dir. Laura Wandel)

Current ranking/score: #11, 86

How to watch: Mubi, rental.

List-worthy?: Honorable mention.

Premise: On her first day of elementary school, seven-year-old Nora (Maya Vanderbeque) is terrified about fitting in and turns to her older brother Abel (Günter Duret) for comfort. But when Nora discovers that Abel is a target for playground bullying, she acts to protect him in kind, with unforeseen consequences.

Sample praise: “This is the first feature from the writer-director Laura Wandel, and it’s a knockout, as flawlessly constructed as it is harrowing.” — Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

Thoughts: To say this Belgian drama owes a little something to two other Belgians, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, is an understatement. Wandel’s over-the-shoulder realism and intimacy with her camera at times gives Playground the feel of a lost Dardennes film, at least in its handheld style and its concern with the vulnerable. But it also had me thinking about the extraordinary 2006 French film Ponette, about a four-year-old girl coping with the loss of her mother in a car accident. For one, Maya Vanderbeque’s performance as Nora, like Victoire Thivisol’s work in Ponette, stands as one of the great feats of child acting. But more importantly, both films tap into the sensitivity and innocence of a little girl who is suddenly forced to cope with the cruelty of the world. In 72 perfectly proportioned minutes, Wandel presents recess as an allegory for how society works, giving Nora an early glimpse of how humans assert power over each other, thwart imperfect (or downright neglectful) authority figures, and act on tribalistic instincts. At the same time, Playground is a heartbreaking and beautiful portrait of a sibling bond that’s powerful but also fragile, subject to forces that can threaten it and change it and possibly defeat it. Through Wandel’s telephoto lens, which stays close to Nora’s face while rendering the space around her blurry and uncertain, school is a battleground.

7. Three Minutes: A Lengthening (dir. Bianca Stigter)

Current ranking/score: #10, 87.

How to watch: In theaters.

List-worthy?: Honorable mention.

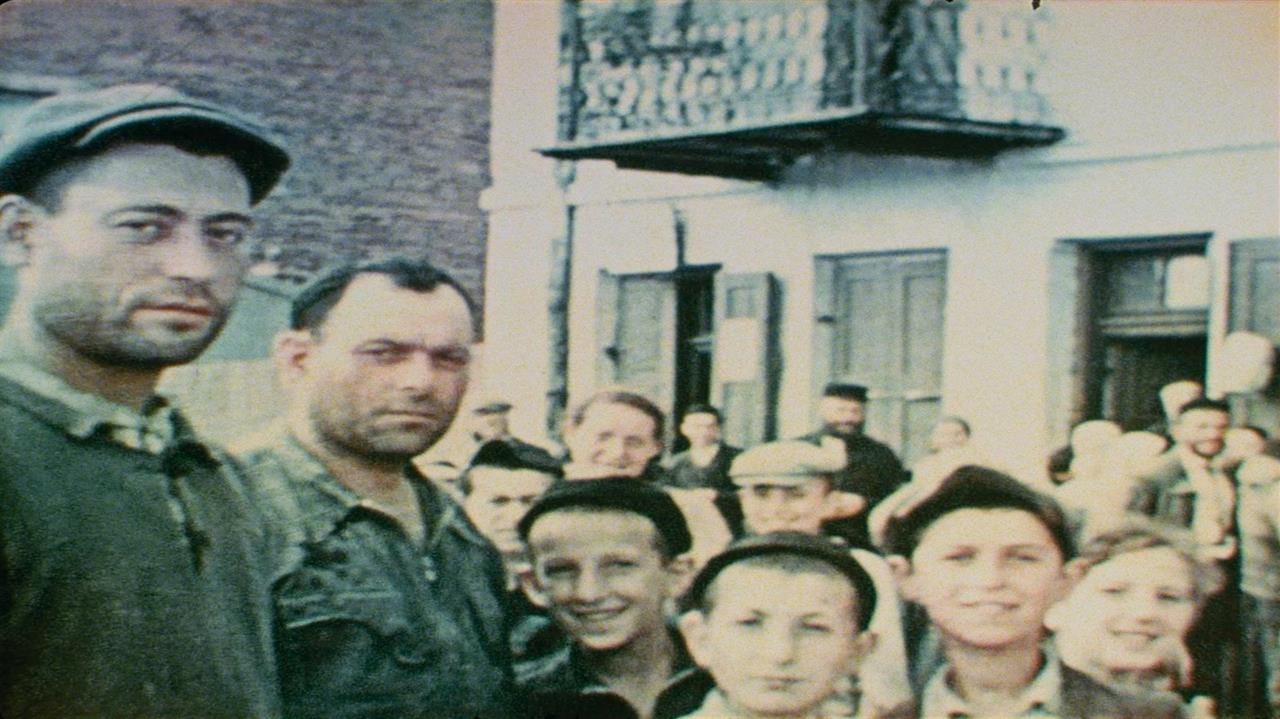

Premise: The discovery of three minutes of 16mm footage from the Polish city of Nasielsk in 1938 prompts an investigation of its origins and a memorial to Jewish residents whose lives would be wiped out by the Holocaust.

Sample praise: “A great film about filmmaking and a quietly devastating memorial for lives long gone.” — Matt Zoller Seitz, RogerEbert.com

Thoughts: As a reclamation project, Three Minutes: A Lengthening calls to mind Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old, which unearthed and technically finessed vintage photographs, footage, and audio to give an impression of what it was like to serve in World War I. Stigter’s documentary only has three minutes of a seemingly unremarkable home movie to work with—though it has been restored and treated to make the images more vivid—but it feels similarly like an effort to use film as memorials to forgotten people. With no talking heads, only Helena Bonham Carter doing narration, Three Minutes carefully situates the footage in a specific time and place: a Jewish enclave in Poland that was about to be ravaged by the Nazis, with very few survivors. And so that footage becomes the only evidence we have of its subjects’ existence, and their mostly carefree faces—before cameras were ubiquitous, everyone loved to smile and clown around when in front of one—are set against the implied fate we know awaits them. It’s a gift to have even this small recognition of their humanity, and a testament to cinema’s power in simply documenting worlds that will change—or simply disappear.

6. In Front of Your Face (dir. Hong Sang-soo)

Current ranking/score: #9/87.

How to watch: Not currently available. Cinema Guild released it to theaters earlier in the year, but a video/streaming date has not been set.

List-worthy?: Juuuust a bit outside.

Premise: After spending many years in America, former actress Sangok (Lee Hye-young) returns to South Korea for reasons unknown, reuniting with her younger sister Jeongok (Cho Yunhee) and taking a meeting with a film director (Kwon Hae-hyo) who wants to collaborate with her.

Sample praise: “One of the South Korean director’s most open films of late, poignant in its use of a simple structure to touch on the eminently difficult question of how to live happily between past, present, and future.” — Elena Lazic, The Playlist

Thoughts: For festival-goers and arthouse mavens, it used to be relatively easy to track Hong Sang-soo’s work. I first encountered his insightful, structurally ambitious relationship dramas back at my first Toronto International Film Festival in 2000, which featured A Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors. But then around 2010, helped along by the ease of modest digital film productions, Hong hit the gas pedal, embracing a new way of making movies that were more intimate, improvised, and autobiographical. As Hong has grown more prolific—he released three films in 2017 alone—I’ve been less consistent about keeping up with his work and frankly less inspired to do so. The last Hong film I loved was 2015’s Right Now, Wrong Then, in part because it reflected the most rigorous approach of his earlier period. So I’m pleased to discover that In Front of Your Face is top-shelf Hong: At the beginning, it seems like the typically loose-limbed, conversational effort you’d expect from his later work, but all its (entertaining) prelude is mere set-up for a revelation that puts everything that came before in a new light. A few long-take conversations between Sangok and the Hong-like director are at the beating heart of a film centered on what it takes to gain control—and a measure of grace—in a life that’s disorderly by nature.

Coming in Part II: Two documentaries about racial injustice, a film by Jafar Panahi’s son, and a #1 that runs a generous 217 minutes.

"... and a #1 that runs a generous 217 minutes."

I'm pretty sure BULLET TRAIN was only 127 mins? Probably a typo.

This is great -- thanks! If you do get a chance to watch A Night of Knowing Nothing, I cannot recommend it strongly enough. It's self-aware, politically engaged, blends documentary footage and fiction in super interesting ways. It particularly resonates with me because of my background, but even without that I think it's an exceptional film.