On Cats on Film

Cats tend to get a bad rap in movies. Do they have anyone but themselves to blame?

In Jack Arnold’s 1957 classic The Incredible Shrinking Man, diminishing protagonist Scott Carey (Grant Williams) discovers that a change in size comes with a clarifying change in perspective. Adapted from Richard Matheson’s novel The Shrinking Man by the author himself (with some rewrites by Richard Alan Simmons), the film takes a page from Gulliver’s Travels, particularly Gulliver’s time among the Brobdingnagians, whose giant size allows him to see just how disgusting the human body and its functions are upon close inspection. Similarly, Scott comes to see his own nicely appointed home as a deathtrap filled with perils like spiders, mountainous staircases, and a cute house cat named Butch who, abandoning all affection when offered easy prey, attempts to treat Scott as his next meal.

This may be the truest depiction of cats ever committed to film. Even those of us who love cats (and there’s a cat in my lap as I write this) understand they’re not really pets so much as companions of convenience. We only pretend to have tamed them. At heart they’re savage beasts who’d probably eat us if they thought they could get away with it. That’s part of their appeal.

It’s also why, as I was reminded by the Criterion Channel’s recent “Cat Movies” selection, depictions of cats (at least in live action films) have always been more complicated than depictions of dogs. The rare exception aside, dogs get treated as loyal, lovable companions. On the whole, movies tend to be a little more wary about cats. Criterion’s “Cat Movies” programming is far from comprehensive (no Harry and Tonto or Bell, Book and Candle, for starters). But if we take the selection as a representative sample, it’s telling that it contains many horror movies: Cat People, Inferno, House and others all play on the suspicion that there’s something about cats not to be trusted. Even one of the fondest entries, That Darn Cat, has a title with frustration baked into it.

In some respects, cats have no one but themselves to blame. Turn a camera on a well-trained dog and you’re likely to get the result you want. Turn a camera on a cat and most of the time you get whatever the cat wants to give you. Dogs crave attention and want to please. Cats don’t care. That’s why it’s easy to rattle off the names of famous dog actors (Benji! Lassie! Rin Tin Tin! Uggie! Hot newcomer Snoop!) but name a single movie cat. Go on. Just one. Though you’ve definitely seen Orangey, the most famous movie cat of all time—cuddling up to Audrey Hepburn on an iconic poster, if nowhere else—his image has outlasted his name.

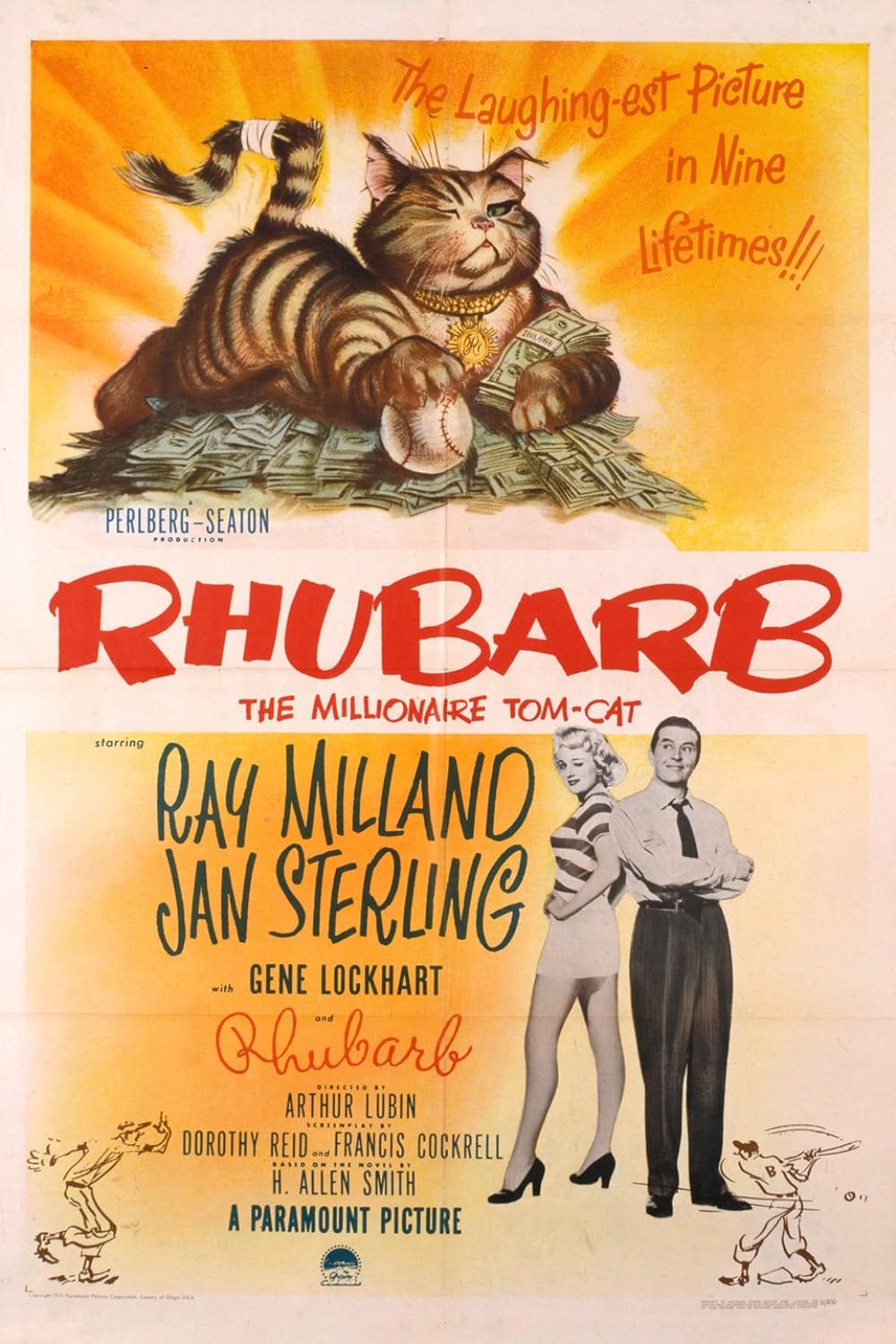

Orangey’s career also partly illustrates why so few cats have had any lasting time in the spotlight. Per the official story, Orangey made his debut at the age of one in the 1951 film Rhubarb, in which he portrays a stray cat who inherits a baseball team from an eccentric millionaire. (It is, as that plot description suggests, an extremely silly movie.) Orangey then worked until the age of 17, picking up countless, sometimes uncredited, assignments, including a bunch of high-profile roles. That’s Orangey who gives up the location of the Frank family in The Diary of Anne Frank. And that’s also Orangey as the unnamed cat who serves as Holly Golightly’s companion in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. And the terrifying cat in The Incredible Shrinking Man?: That's Orangey, too. The tabby stayed busy for years before retiring after guesting on Batman alongside Eartha Kitt.

Except the Orangey story isn’t quite that simple, as critic and filmmaker Dan Sallitt discovered when, stirred by the performance of a cat who may or may not have been Orangey in Jacques Tourneur’s Stranger on Horseback, he went down an Orangey rabbit hole and emerged with the essay “The Hardest Working Cat in Show Biz.” Orangey, it turns out, was part of a stable of animals trained by Frank Inn, whose long career working with Hollywood animals included time with Benji and Green Acres’ Arnold Ziffel. By way of the blog Teh Kitteh Antidote/Anecdote, Sallitt arrived at the book Amazing Animal Actors, which reveals that Inn used 36 cats, each specializing in one skill, to make Rhubarb because training a cat to do more than one trick proved too daunting. The practice of bringing in multiple Orangeys didn’t stop there. Look closely at Breakfast at Tiffany’s and it becomes clear that at least two cats play the role, as another blogger pointed out.

It’s an easy enough trick to pull. A key stretch of Rhubarb even hinges on cats being hard to tell apart from a distance, which predicts a twist in Inside Llewyn Davis years later. (Once, when my daughter and I discovered our cat had somehow slipped out of the house and wandered up to greet us when we pulled in our car, I wasn’t entirely sure she was our cat and not one of our neighborhood’s lookalike strays until after she let me pick her up.) But it’s hard to make a cat a household name when they’re secretly multitudinous. Not that Inn didn’t try. A widely reprinted 1951 profile by Erskine Johnson noted that Orangey, or at least the Orangey introduced to Johnson, had “slant eyes like Myrna Loy, cheeks like [Hungarian character actor] S.Z. Sakall, claws like a leopard, and a disposition like Fu Manchu.” In the piece that follows, it’s those last two descriptors that get the most ink, to the point where Inn seems to be playing up Orangey’s heel-like qualities. “This cat’s meaner than an ordinary cat but he’s no ways as deadly as a mountain lion or any big cat. [But] you can get hurt just as quick. This guy bites deep.” With human friends like Inn, who needs human enemies?

Ten years later, Inn seemed to have given up the game. Orangey was sometimes known as Rhubarb (blurring the line between the real cat and the fictional one), Orangey Minerva (after his character on Our Miss Brooks), and 0ther names. (In contemporary terms, the “Orangey” brand was not strong.) Speaking to an anonymous wire reporter in 1961, Inn freely reveals that there are many Orangeys/Rhubarbs, including Oscar, Little Boy, Golden Boy, and Little Britches. But there also seems to have been an Orangey/Rhubarb Prime, “Old Rube” as Inn calls him. By this point Old Rube, now 19 (a detail that throws the accepted Orangey timeline out the window), primarily played parts that called for sleepy cats that didn’t need to move around a lot.

Inn, by all reports, was a true animal lover with a menagerie that included not just performing creatures but strays who needed homes (a stark contrast to some of the nightmarish stories that have emerged about the treatment of other movie animals in the pre-, and even post-AHA era). But even he seems to have understood that selling his prize cat as a sweet and lovable cuddlebug would never work, or at least not on anyone who’s spent time with a real-life cat.

Cats aren’t natural performers but they can be fascinating subjects when allowed to be themselves. That’s why some of the most successful scenes with cats in movies have been unscripted. The cat Don Corleone pets in the opening scene of The Godfather was a stray Francis Ford Coppola found wandering around the Paramount lot and handed to Marlon Brando shortly before shooting began. Its loud, satisfied purring made it necessary to re-record some of Brando’s dialogue. But it also made the scene, complicating our first image of the powerful mobster by displaying his softer side. Ever generous with his actors, Robert Altman let Elliott Gould’s feline co-star in The Long Goodbye improv his loud demands for cat food—Courry brand cat food, specifically—until Gould’s Philip Marlowe gives up and goes to the grocery at 3am after attempting to placate the cat with whatever’s laying around the kitchen. Rarely has the truth of living with a cat been presented in such an unvarnished fashion.

Maybe that’s why cat videos have enjoyed such success and Oscilloscope's Cat Video Fest makes the rounds year after year stuffed with new entries and classic clips. The subtext to most cat videos is humiliation. Look at those cats, prancing around, thinking they’re so smart! Watch as they fall off various objects / get frightened by the Roomba / gets their heads stuck in boxes / etc.! The unspoken sense underlying cat videos, and cat movies on the whole, is sure, we love cats, but they definitely need to be taken down a peg or two, right?

Perhaps cats just need a film told from their point of view. Apart from documentaries, the best example I’ve seen can also be found in Criterion’s Cat Movies selection, a 1969 short called “The Perils of Priscilla.” Directed by Carroll Ballard a decade before The Black Stallion made him the premier director of artful and thematically complex animal movies, it sticks close to the perspective of a siamese cat named Priscilla, sometimes even using frenetic point-of-view shots. The story is simple: left alone while her family vacations, Priscilla leaves the safety of her house after a dog eats her food. She then wanders aimlessly around the streets of Los Angeles, dodging speeding cars and other threats, before ultimately becoming one of many strays in the pound. (The Pasadena Humane Society sponsored the film.)

It’s a dizzying 17 minutes that immerses viewers in Priscilla’s mind as she first makes the familiar rounds of her home (where she only has a handsy toddler to worry about) then plunges into the chaos of the unfamiliar wider world. Ballard makes no attempt to anthropomorphize Priscilla. She’s affectionate enough with her family but, above all, she’s a cat committed to doing what cats do: skulking about, looking for food, napping, and fleeing all possible threats that can’t be scared off with hisses and flashing claws. Ballard doesn’t doesn’t try to make her endearing or sympathetic, but she is anyway, simply by being herself—even if she clearly wouldn’t hesitate to devour her careless human companions if they shrank to mouse size.

Offended on behalf of the entire French New Wave that there's no mention here of DAY FOR NIGHT, where a whole sequence of the movie is devoted to how hard it is to make the stupid cat do what it needs to do for one scene -- which is just to walk over and drink some milk -- to the point where they throw the damn cat at the milk. Great scene, great movie

Just taught "Rear Window" last week and have been thinking a lot about the animals in that film. There's the well-known little dog (sad), gulls on the rooftop, a few pigeons, and, prominently in the first bit of movement in the film, a cat. Then there are other cats, if you can spot them. What's interesting here (at least to me) is the placement of animals in a built environment. There are no accidental animals in this constructed courtyard. Hitchcock following that opening cat can start to seem meaningful: curiosity, stealth, and so on. Sometimes birds are just birds. Until they aren't.