'Fly Away Home': How to talk to children about death (and life)

Carroll Ballard's gorgeous 1996 adventure is a rare and precious example of family entertaining willing to engage in the toughest conversation.

If you’ve been a parent in the 21st century, you’re likely familiar with the work of Mo Willems, the enormously gifted author of children’s storybooks like Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! and the Knuffle Bunny and Elephant & Piggie series. Willems’ books are often infectiously silly—my girls would both scream “NO PIGEON!” at the top of their lungs to keep that pesky pigeon from getting behind the wheel—and sometimes impart simple life lessons, as when Elephant pauses to consider sharing his ice cream with Piggie because he imagines his best friend might need some cheering up. (That one has a sweet twist ending.) Willems writes with whimsy, soulfulness, and a beautiful economy of languages that’s reflected in the clarity and simplicity of his illustrations.

When Willems’ published City Dog, Country Frog in 2010, we added it to our collection sight unseen, and as I first read it to my four-year-old daughter at bedtime, a lump caught in my throat unexpectedly. The story unfolds in seasons, starting in spring, when a city dog goes off leash in the country, bounding around in the tall grass and streams, until he meets and befriends a frog. The frog teaches the dog some “country games.” In the summer, the dog shows the frog some “city games.” But the life cycle of a frog is short, and when fall rolls around, the frog doesn’t have the energy to keep up with the dog. And so they play “remembering games,” reflecting on all the fun times they had together. When winter comes, the dog looks for his friend again. His friend is gone.

That’s not the end of the story, of course. The next spring, the dog meets a new animal friend in the country, but he carries the memory of the frog with him, because that’s what we do when those we care about die. That’s how they continue to live.

Of all the conversations you need to have with your children, the one about death is the hardest—and, as a consequence, the one most family fiction avoids, even when a missing parent is a key part of a premise. I was grateful for the stark simplicity of Willems’ book, which doesn’t deny the grief and finality of death, rendered in an empty winter landscape, followed by the words that country frog was gone. And I was also grateful that the answer to the toughest question, “What happens after death?”, didn’t drift off to froggie heaven, but to the next season here on Earth, where a page is turned and the dog can feel grateful for the time he had with his friend.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

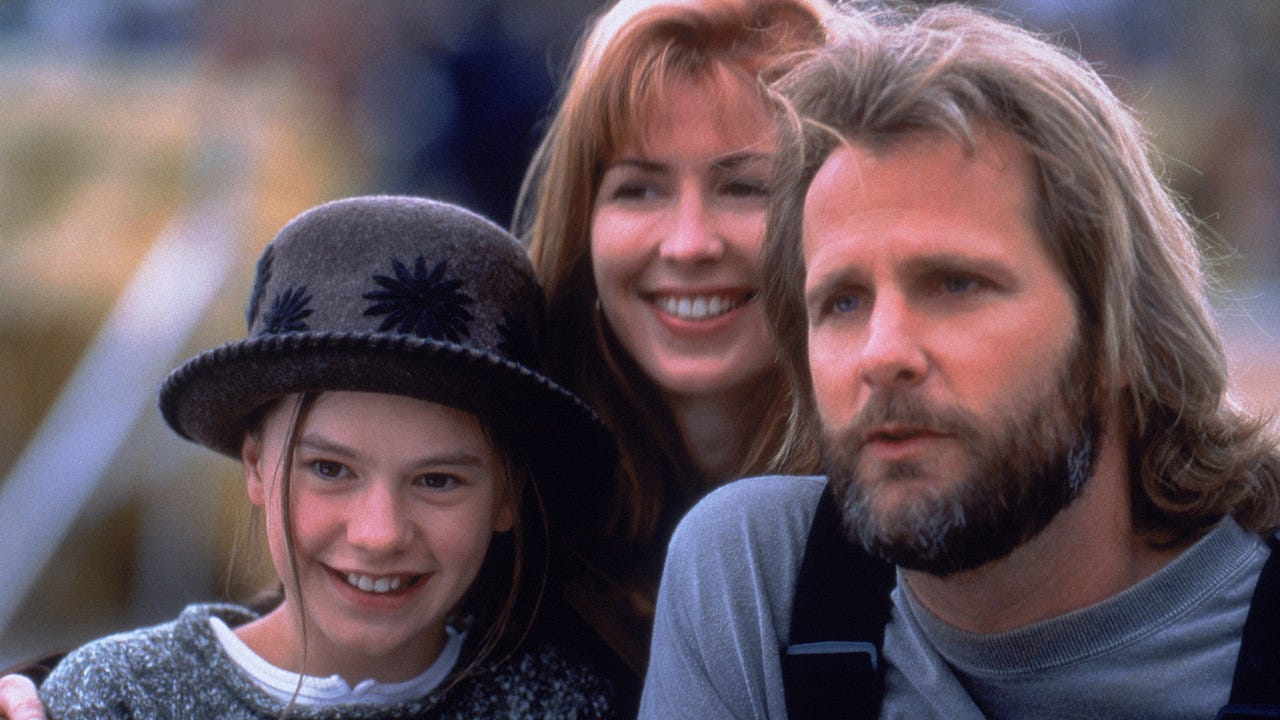

Carroll Ballard’s beautiful 1996 children’s adventure Fly Away Home has the same rare integrity, which is why it’s among my most cherished live-action children’s films. It has the audacity to open with the last moments a child spends with her mother before a car accident separates them forever. The sequence is wordless, set to Mary Chapin Carpenter’s lovely song “10,000 Miles,”and the accident itself is elegantly staged, seen through a rain-spattered windshield that cracks as the car—and our perspective—wheels out of control. Though not graphic in the least, it’s as firm in its finality as Willems’ winter landscapes. The next shot is of Jeff Daniels’ Thomas as he waits for his daughter to regain consciousness in the hospital. Her question “What are you doing here?” is answered by his eyes. Nothing else needs to be said. Her mother is gone.

As a director, Ballard has a rare interest in reminding young audiences of their connection with the natural world. In this, along with the ecstatic beauty of his exterior photography, he could be compared to Terrence Malick. His most famous work, The Black Stallion, has an extraordinary stretch where a boy, marooned on an island after a boat accident that claims his father, forges a bond with a horse that will take them both to unimaginable places. So long as mankind doesn’t make devastating encroachments on our ecosystem—a concern that’s a big part of Fly Away Home—nature always holds the opportunity for renewal, and death often acts to seed new life.

For Amy, the grieving process is confusing and difficult, especially around a father she doesn’t know well, much less trust as a caregiver. He’s an artist, inventor, and environmental gadfly who’s been living on a farm in Ontario while she’s been half a world away with her mother in New Zealand. Her room has become a storage space for his metalworks and assorted clutter, and he’s a disaster on the day-to-day work of making meals, getting her ready for school, and the other domestic details that he perhaps left to his ex-wife when they were together. His parenting skills are rusty, but he proves to be an excellent father where it counts.

Fly Away Home turns on an act of unmissable symbolism, with Amy, a motherless child, instinctually becoming a mother herself. When a nearby construction project plows through a goose’s nest, Amy picks up the abandoned eggs and sets up an incubator in a dresser. Thomas doesn’t discover what’s happening until the eggs hatch and the baby geese recognize Amy as their mother, which is a more complicated proposition than the usual “Can we keep it? Can we keep it?” plea when a kid finds a stray cat or dog. As wild geese, they need to fly south for the winter, and without a mother to guide them on that journey, they’re likely to go dangerously astray. When a local ranger finds out about Amy’s birds, he whips out a pair of nail clippers to render them flightless, insisting it’s the humane thing to do. Thomas shows him the door.

Based loosely on a true story, Fly Away Home follows Thomas and Amy as they attempt a crazy solution to the problem, which is to use Thomas’s aviation know-how to create a glider for Amy and train the geese to follow her on a flight path to a nature preserve in South Carolina. Ballard embraces Thomas as an eccentric, environmental radical, much like he did his biologist hero in Never Cry Wolf, his first-rate Disney survival drama about a man living among Arctic wolves on the Canadian tundra. There’s a shot of Thomas running out of the house in his underwear one morning, trying to chase off the bulldozers chipping away at the borders of his property. He’s a righteous lunatic. He’s also a father who’s going to absurd lengths to fulfill a seemingly impossible promise to his daughter.

The showdown between Thomas, Amy, and the assorted rangers and developers who stand in their way is the weakest element of Fly Away Home, because the villainy of their adversaries is either cartoonish or unfair. But the heart of the film is the startling beauty of Amy honoring the memory of her own mother by taking on the role herself at such a young age. And for all the madness inherent in his migration plan, Thomas does what a good father is supposed to do—support and encourage a child as they grow into the person they’re destined to be and then stand in awe as they assert their independence.

The aerial photography, by the great cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, supplies endlessly gorgeous images of migrating formations drifting through the countryside, passing over reflective ponds and pockets of civilization. The care Ballard and Deschanel put into the visual splendor helps to emphasize the way Mother Nature can assert herself during difficult times, forcing a perspective that we might have trouble arriving at on our own: A car accident may itself be an unnatural way to die, but death itself is natural, even when a loved one is gone much sooner than expected. In that sense, Fly Away Home feels like a successor to Bambi, which features one of most infamous unnatural deaths in film history, but folds it into a story about the circle of life.

Disney doesn’t make movies like Bambi anymore, and studios don’t make movies like Fly Away Home, either. While it’s still common for a young protagonist to not have a parent, it’s uncommon for films to square up to the grieving process, rather than treat death merely as an obstacle to overcome. Amy does find her way through this terrible loss, but Fly Away Home is about how doing so brings her closer to her mother. At the tail end of her journey, as she flies that last leg solo, Ballard brings back the title song, making the touching suggestion that Amy’s mom is her eternal companion.

Fly Away Home is currently streaming on HBO Max.

Oh, holy crap! I actually saw the opening scene of Fly Away Home randomly on TV when I was a young child many years ago. The scene has stuck with me ever since, but I didn't catch the movie's title back then, so for maybe two decades now I've been wondering what that "car accident" movie I saw as a child was. But today, reading your description of the opening suddenly got alarm bells ringing in my head... I race to YouTube, bring up the scene, and... YES! This is the exact same movie I saw back then, that I've been looking for for all these years!

I don't remember if I actually watched the entire film back then (my memory is very hazy past the opening, so likely not), but now I'll have the opportunity to do so. Thank you Scott!

dammit, Scott. your discussion of City Dog, Country Frog made me tear up