Minding the Gaps: 'Walking Tall Part 2' (1975): "My children are motherless because of the man at the top"

A sequel to an unexpected hit doubles as a window into how legends get formed and a past decade's hunger for tales of backwoods justice.

Minding the Gaps is a recurring feature in which Keith Phipps watches and writes about a movie he’s never seen before, selected at random by the app he uses to catalog a DVD and Blu-ray collection accumulated over 20+ years. It’s an attempt to fill in the gaps in his film knowledge while removing the horrifying burden of choice. This is the second entry. You can read the first here.

He was always at war with Them. It was Them that made his hometown unrecognizable, polluting the county line with dens of vice filled with illegal booze, prostitutes, and fixed games of chance. It was Them that, after he called out their depravity, cut him up and left him to die by the side of the road. It was Them who sent poison hooch down from the hills. It was Them that did their best to make sure he never became Sheriff of McNairy County, Tennessee. It was Them that killed his wife, shooting her in the head as she rode beside him. It was Them who left him alone to raise his kids, Them who pressed charges when he welted the backside of a reprobate who beat his son, Them raised hell because he cuffed some juvenile joyriders together and made them rake the grass in front of town hall.

The moonshiners, the State Line Mob, the politicians on the take, the bleeding hearts: Them.

In the end, it was Them that killed him. Even if no one could prove it, he knew, and he told the truth to moviegoers. “I had to stand up for myself alone, and you know what they did to me,” he warned from beyond the grave. “Until all men stand up for what they believe in, the same damn thing could happen to any one of you.” The war never stopped. Not even death could end it.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

That’s the story of Buford Pusser, as told across three movies — Walking Tall, Walking Tall Part 2, and Final Chapter: Walking Tall — released between 1973 and 1977, an era of uncertainty and cultural upheaval in which the unexpected success of the first film turned the real-life Pusser, an actual sheriff, into a symbol of two-fisted, no-nonsense, old-fashioned justice. But the story of Buford Pusser had begun to spread even before the movies made him a national figure. A hulking figure — 6’6”, 250 pounds — he was born and died in Tennessee, his time in the state interrupted only by a brief stint in the Marines and a longer stint wrestling in Chicago under the name Buford the Bull. It was back home, however, where he made his name. A visit to a seedy spot called the Plantation Club left him feeling cheated. Words turned to blows, leaving Pusser on the losing end of the confrontation. The scars on his torso would serve as a reminder every time he looked in the mirror. He bided his time, returning years later to wreck the place and send the owner to the hospital.

Though he stood trial for the assault — and lied about his whereabouts to earn an acquittal — that 1959 incident doubled as an audition. His father had been the police chief of Adamsville, Tennessee. In 1962, the younger Pusser took the job himself. In 1964, he became Sheriff of McNairy County, at 26 the youngest person ever elected to the position. Pusser burnished his rep by continuing to play rough. By 1968 he’d killed two people in, he said, self-defense, though no witnesses were around to back up the claims. His enemies played rough, too, killing his wife Pauline in an ambush in 1967. That scarred Pusser, figuratively and literally. A shattered jaw left him with a shattered face to match his already damaged his body.

The date of Pauline’s death became the title of Pusser biographer W.R. Morris’s The Twelfth of August: The Story of Buford Pusser. By the time it was published in 1971, Pusser was no longer sheriff, vacating the job due to term limits, but that didn’t stop snowballing public interest in his life. In 1970, Memphis musician Eddie Bond released “The Ballad of Buford Pusser,” a song that compared Pusser to Wyatt Earp and lamented the “dirty rotten world that took his wife.” Outside rockabilly circles, Bond still remains best known for telling a young Elvis Presley not to quit his day job, but the song was successful enough to help bring Pusser to the attention of Bing Crosby Productions, which borrowed a line from its lyric for the title of its Pusser biopic: Walking Tall.

If Morris and Bond’s encomiums were both print-the-legend affairs, Walking Tall plays like a legend turned into a blurry mimeograph; any resemblance to what really happened in those roadhouses and backroads is now vanishingly faint. It’s also become quite flattering. Directed by Phil Karlson, no stranger to tough crime stories thanks to films like The Phenix City Story and Kansas City Confidential, the original Walking Tall depicts Pusser as an innocent who returns from the big city to find the rural Eden he left behind corrupted by greed and sin. To combat it, he turns a hunk of oak into a justice-administering club, equally well-suited to smashing slots and busting heads.

In the role that made him a star, Joe Don Baker plays Pusser as a man burning with righteousness. Tender with his wife Pauline (Elizabeth Hartman) and kids (played by real-life siblings Dawn Lyn and Leif Garrett) he takes on injustice whenever he sees it, even calling out his father (Noah Beery Jr.) for harboring prejudice against Buford’s Black friend Obra (Felton Perry). And, sure, Buford uses the n-word in front of Obra, too, but it’s just because he’s so mad that Obra won’t give up the name of the moonshiner who poisoned a bunch of Black picnickers, all of them civil rights workers. The movie’s assumption: When you live to administer justice, you do what you have to do to get people’s attention. And, besides, Walking Tall asks us, how bigoted can Buford be if Obra agrees to become his deputy? Look, one of his best friends is Black.

It’s tough to call Walking Tall a good film, but it’s a highly effective one, made with enough manipulative skill to draw in even those on guard against bullshit. There’s always been a dark side to Roger Ebert’s famous description of movies as “empathy machines.” They can also make viewers empathetic to despicable acts.

Karlson has no use for subtlety. How can you not be on the side of a man who loses his wife to the bad guys but also, in an equally tearful scene, his dog, whose bloody corpse he carries into his living room after a drive-by shooting? Baker, on the other hand, is subtle. He plays Pusser with wide-eyed sincerity that, when warranted, gives way reluctantly—but thoroughly—to sadistic glee. And it’s warranted a lot. Walking Tall ends with Buford — his face still covered in plaster from the ambush killing his wife — committing cold-blooded vehicular homicide. It’s a moment designed to send audiences away cheering.

And it did. A hit in the South, outgrossing The Godfather in some markets south of the Mason-Dixon line as it rolled across the country after its November 1973 premiere, Walking Tall made its way north in 1974 where it performed well and attracted the attention of critics who didn’t always encounter drive-in fare. In The New Yorker, Pauline Kael dubbed it a “street Western” and likened it to Dirty Harry, anointing Pusser the modern descendant of the Western hero now that “the Western is dead.” Kael also dubbed it “pre-political,” and though Karlson told the New York Times he just wanted to make a movie “in which people will learn respect for a decent lawman,” as opposed to the attitudes prevalent in films like The Godfather and The Getaway, this seem a little naive, perhaps intentionally so.

All of which is a long wind-up to the true subject of this column, Walking Tall Part 2, which I’d never seen before, a film that, on its own, is kind of meaningless without the context around it. So I watched Walking Tall to prep for it, and then, figuring that, like Pusser, I should finish the dirty work I’d started, I watched the final installment, Final Chapter — Walking Tall. (There’s also a TV movie starring Brian Dennehy, a short-lived ’80s TV series, a sort-of remake starring Dwayne Johnson released in 2004, and a couple of direct-to-home video sequels to that film starring Kevin Sorbo, but the original trilogy felt like enough.)

In the process, I realized I couldn’t entirely write myself out of the story. Back in the early days of The A.V. Club, I used to work under a Walking Tall poster I’d scored off eBay with a bunch of other ’70s movie posters. (The combination of earning an OK paycheck for the first time in my life and the easy availability of ephemera once confined to specialty shops, warehouses, and collectors’ basements inspired some weird purchases in the late-’90s.) I thought it was funny. Here was a half-forgotten piece of culture I could celebrate with more than a touch of irony. And it’s not like I didn’t like the film, sort of. I enjoyed, and still enjoy, vintage sleaze and exploitation and found the film’s combination of self-righteousness, violence and retrograde politics faintly hilarious.

Reviewing the film for its DVD release a few years later, I called it “an unconscionably good time.” My view hasn’t really shifted, but watching it now, the distance between 1973 and now, and the fantasy of a strongman with a clear sense of right and wrong laying down the law now feels less distant than it did 20 years ago. I justified my real pleasure in such material with something of a camp detachment, never interrogating it too deeply. We treat these fantasies of power, revenge, and the violent administration of justice as kitsch siloed safely away in the past at our peril.

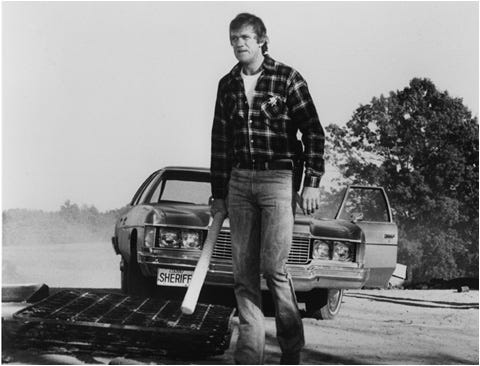

I returned to Pusser's crime-ridden McNairy County, curious what I would discover. Though I’d seen Walking Tall before, I’d never checked out the sequels, in which the towering, muscular, Swedish-born Bo Svenson takes over for Baker. It was a role he was never supposed to play. On August 21, 1974, Buford Pusser signed a contract to play himself in the first Walking Tall sequel. That night, he died in a single-car accident while driving home from the McNairy County Fair. Rather than casting a shadow over the subsequent Walking Tall films, Pusser’s real-life death fed their paranoid central narrative. Rumors arose that it had been no accident. Pusser’s mother spent years trying to prove he’d been killed, and the sequels simply treated that belief as fact, allowing Pusser to take on the aura of a martyr.

Walking Tall Part 2 picks up more or less where its predecessor leaves off, with a still-bandaged Pusser resuming his duties and seeking to root out corruption. Like the original, which also featured Sam Fuller favorite Gene Evans in a supporting role, it benefits from some smart casting. Bruce Glover, one of the few constants in the series, returns as Pusser’s loyal deputy, Luke Askew and Richard Jaeckel play a pair of colorful villains, and Robert DoQui — a familiar face thanks to films like Nashville and RoboCop — takes over as the doomed Obra. (Maybe it’s a little bit to the series’ credit that it doesn’t kill off the most prominent Black supporting character until the second movie.) Otherwise, filled with shotgun blasts and backwoods car chases, the sequel is mostly interchangeable with other ’70s movies set in a cartoonish South that the original Walking Tall helped inspire.

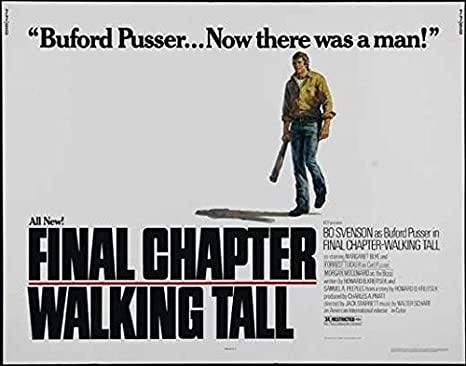

It ends, as before, in violence, with a blood-drenched Pusser emerging from a showdown in which he kills the bad guy. (He doesn’t want to, being a lawman, but of course he has no choice.) As he drives away, exhausted, the soundtrack abruptly drops as text informs audience of the real Pusser’s death, casting that death in a suspicious light. What serves as a coda to Part 2 becomes the nucleus of Final Chapter, which opens with the voice of Pusser (as played, again, by Svenson) speaking from beyond the grave and ends with a fiery crash that serves as the culmination of the usual showdowns and blows traded with local organized crime.

An attempt to bring Pusser’s life full circle, Final Chapter is the strangest of the three films. After losing an election thanks to criticism from a liberal public defender, Pusser spends much of the middle stretch in a state of humiliation and on the brink of financial ruin, until a Hollywood producer catches wind of his story and makes a movie of his life. In the third act, Pusser watches the making of the original Walking Tall, breaks down watching its bloody final scene at the premiere, then signs a contract to play himself in the sequel on the day of his death. (It’s a bit like the second half of Don Quixote, only with a beefy Tennessee lawman instead of a deluded Spanish noble.)

Time has a funny way of flattening out history. Walking Tall met with great success but also opened Pusser up to criticism. Or, more accurately, it gave criticism that already existed a national spotlight. Under the headline “How Tall Did Buford Pusser Really Walk?” People looked askance at the film’s glorification of Pusser, noting that McNairy County had opted not to reelect him when he ran again in 1972 and including choice details from Pusser’s hometown:

Bruce Hurt, publisher of Selmer’s weekly Independent-Appeal, sums up the local view of Pusser: “There is a small percentage of the county which idolizes him, another small group which thinks he should be punished as a murderer, and a lot of people who don’t really have an opinion but who think the things that happened were unfortunate.” Interestingly, while Walking Tall is the biggest grossing film in Tennessee history, in the Selmer drive-in (the town has no indoor movie house) it lasted only a few days.

Inspired by the film’s success on its own local screens, the Dayton Daily News sent journalist Cammy Wilson, who grew up in Mississippi not far from Pusser’s turf, to investigate. Wilson emerged with a dark portrait filled with stories of abuse, not just of criminals. Buford’s stepdaughter, who fled the Pusser home, recalled a conversation with Pauline in which she said things were “going bad” with Buford shortly before her death. Where allegations ended, rumors of payoffs and affairs began, along with questions about why no one could substantiate Pusser’s story of Pauline’s death.

Closer to home, the Jackson Sun’s Delores Ballard saw on the occasion of Pusser’s death a chance to reassess the sheriff’s legacy, writing “those too far from McNairy County to know that the Pusser image they worshipped was considered a Hollywood humbug back home reveled in the idolatry of the man they wanted Buford to be. […] Whether bigger-than-life ideal figure or just a man, Buford Pusser is dead.”

Fifteen years later, the same paper published an article, also penned by Ballard, whose headline read “Legend Still ‘Walking Tall’: McNairy Proudly Keeps Pusser Memory Alive.” The piece referred to Pusser as a “tough-looking, misunderstood giant” and ran next to a smiling picture of Pusser’s daughter Dwana posing next to his picture and holding the big stick central to his lore. It includes details about the Buford Pusser Home and Museum. It’s still standing, and still open to the public. Its gift shop sells hats, keychains, and a boxed set featuring all three original Walking Tall films.

Walking Tall is currently streaming on Hulu and Paramount+. Walking Tall Part 2 and Final Chapter: Walking Tall are available as part of Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray and DVD set The Walking Tall Trilogy.

Next: The Devil is a Woman (1935)

Also, I didn't find room to mention it in the piece, but Drive-By Truckers' great album THE DIRTY SOUTH, featuring two songs about Pusser, helped soundtrack my writing. https://open.spotify.com/album/6MaUJWhC6jQJL84AH1MNWy

Glad you spotlighted this one in your anniversary post. Relatively new subscriber.

This brought back a fresh whiff of memories though I've never seen any of the original films. They were out at a time when a lot of movies were unreachable due to age and restrictive parents. So I experienced a great many of them strictly through newspaper ads and the occasional TV spot. Which of course meant that every one of them delivered on the promise of the ad. They had to, didn't they? They wouldn't let them promise something the movie doesn't provide. I only wished I could see the actual movie to prove the verity of the ads.

I've seen enough of them (and BILLY JACK for some reason was one my parents took me to) to learn that there's a drop-off between promise and product more often than not.

But WALKING TALL looms large. I remember a roadtrip (at the time that was the only kind of trip the family could manage) where my mom read chapters of Pusser's book out loud during the drive. It was either that or dad's Perry Como tape. It was one of those things that made life seem it was surrounded by danger, evil sharing the road with you and taking action if provoked. Maybe that part is more accurate than the ads, but it created a certain kind of dread you just carried around with you. I'd forgotten a lot of this and reading this brought back just how much these movies pervaded back then. Thanks for this redneck Proustian moment.