Minding the Gaps: 'The End of Summer' (1961): “Until the moss grows”

A column dedicated to watching a previously unseen movie chosen at random kicks off with late work by a Japanese master

With Minding the Gaps, Keith Phipps writes about a movie he’s never seen before, selected at random by the app he uses to catalog a DVD and Blu-ray collection accumulated over 20+ years. It’s an attempt to fill in the gaps in his film knowledge while removing the horrifying burden of choice. This is the first column.

A few words of explanation before we kick off this new column: I own a lot of movies. I was an early DVD adopter, purchasing my first player in August of 1998, a bargain from the returns section of a Best Buy in Madison, WI. I purchased it alongside discs of L.A. Confidential and Boogie Nights, two of my favorite movies from the previous year, and never really looked back. In the years since, I’ve bought a bunch of movies and had even more sent to me for review consideration. While some I’ve let slip away, reckoning I’d never need to catch, say, Elektra or Scary Movie 2 again, I’ve kept almost everything that looked mildly interesting., thinking “Surely I’ll get to this someday.”

But, to paraphrase the last hit released by Creedence Clearwater Revival, someday never seems to come for a lot of these movies. When I have time to watch a movie of my choosing, it’s easiest to pick something that might be useful for work, a new release we might talk about on The Next Picture Show or something relevant to articles I might pitch. So, hello The Suicide Squad. See you later, An Unmarried Woman. I remain a fan of physical media and have no regrets except one: I don’t think I’ll get to all these movies in my lifetime. This column is an attempt to see to as many as possible, one unwatched film at the time.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

Here’s how it works: To catalog my collection I use an app called MyMovies, made by extremely meticulous Danish developers. I’ve found it reliable and useful, but for the purpose of this column its key feature is the mobile version’s ability to choose a title at random. All you have to do is shake it.

Here I’ll be writing about what shakes out, starting with a late film from a Japanese master.

Yasujirō Ozu is the rare filmmaker who can stir the heart with the image of neatly arranged empty sake barrels resting at an angle outside a brewery? The barrels serve as the focus for three shots that arrive about twelve minutes into The End of Summer (1961), each drawing viewers a little closer to the interior of the family-owned sake brewery at the story’s heart. They’re lovely examples of Ozu’s famous pillow shots, images of exteriors or rooms or inanimate objects that reveal where we are while also establishing how those settings feel.

Like much in Ozu, it’s a device that picks up power through repetition, both within the film and across his filmography. It’s possible to watch and enjoy, even love, a single Ozu film. (I suspect a lot of viewers’ Ozu experience begins and ends with Tokyo Story, a film deservedly ranked among the greatest ever made.) But there’s a cumulative power to watching Ozu films, a power that has a lot to do with the way they circle back to the same themes and cast members while employing slight variations on his style.

Ozu’s one of my favorite directors, but writing that, to be honest, makes me feel a bit like a poseur. I’ve seen at least a dozen of his films, but Ozu was prolific enough . That means many corners of his career remain unknown to me, like, until just now, The End of Summer. And while I now wonder why it took me so long to get to it, I also find it kind of heartening to know that there are films this remarkable from directors I love, still waiting for me to find them.

Nothing else feels like an Ozu. His films tend to be scrupulously limited in their scope, taking place in just the few locations frequented by their central characters. (That’s part of why Tokyo Story, with its several journeys, plays like such a big swing in the context of Ozu’s career.)

The BFI’s Leigh Singer succinctly describes the Ozu style:

Few filmmakers are as consistent in their cinematic style as Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu. From the careful, low-angle framing (as if seated on a tatami mat) and conversations often shot head-on, to his exclusive use of a 50mm lens (most equivalent to the human eye’s perspective) and minimal camera movement, any diversions from these refined parameters are rare. The sudden use of a crane shot in Late Spring (1949) almost has the shock value of the Psycho shower scene.

Ozu’s penultimate film, The End of Summer is even more haunted by death than his swan song, the following year’s An Autumn Afternoon. It takes a while for this to become apparent, however. In fact, it takes a while to understand The End of Summer’s focus since it gives almost equal time to three subplots seemingly related only because they occur within the same family, the Kohayagawas of Kyoto. (The film’s Japanese title translates as “Autumn of the Kohayagawa family,” which provides a sense of foreboding that its English equivalent lacks.) Nakamura Ganjirō II (an Ozu veteran who also appeared in films from Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Imamura, Ichikawa and my beloved Kwaidan by Masaki Kobayashi) plays Manbei, the widowed patriarch who, much to the chagrin of some family members, has resumed relations with Sasaki (Chieko Naniwa), a mistress from an extramarital affair conducted nearly two decades prior. This also includes resuming relations with Yuriko (Reiko Dan), his grown daughter (maybe) from that affair.

In a line that’s somewhat shocking in its frankness in this context, Sasaki reminiscences with Manbei about the “night you turned me into a woman.” But with Sasaki, she’s even less coy, shrugging off the question about whether or not Manbei or some other man she’d previously called her father. Among the film’s questions: does Manbei know he might be the subject of deception? And if so, does he care? Does he choose not to buy the mink stole Yuriko crassly requests (and requests and requests) because he doesn’t have the cash, or because he knows better? Is he just treating his afternoon escapes to see Sasaki as lighthearted attempts to recapture the freedom — however illicit — of an earlier moment in his life?

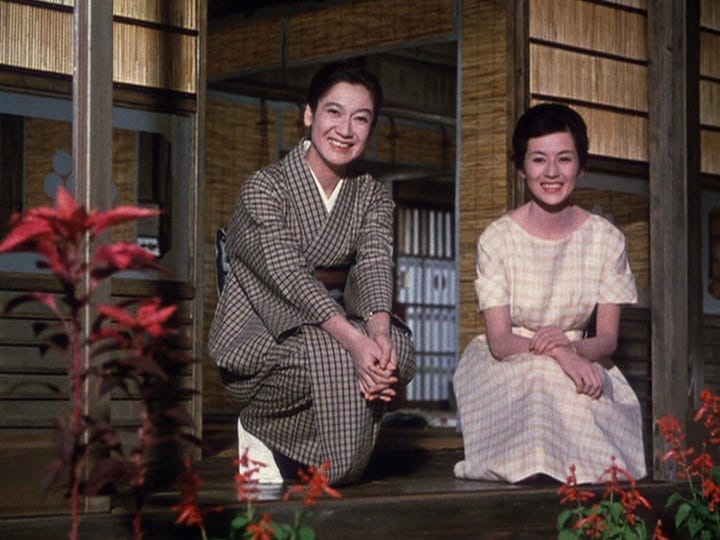

Ozu is content to leave these unanswered, maybe in part because Manbei’s behavior seems to be in denial of where he is in life, even though his conversations with Sasaki are laced with gentle laments about the passing of time. That’s also a factor in the choices faced by Manbei’s daughter Noriko (Yoko Tsukasa), whose unmarried status causes others to seek a suitable match for her, unaware that she pines for a friend from work who’s recently departed for faraway Sapporo. Noriko confides in Akiko (Setsuko Hara), her widowed sister-in-law, the subject of even more aggressive matchmaking attempts. (The film opens with a scene that anticipates Takashi Miike’s Audition, of all films, as Akiko is unknowingly paraded before a would-be suitor for approval.) As usual with Ozu, the question of what one generation owes to another, who gets to pursue happiness, and who gets left behind are central to the film, but they’re tangled together in ways that make them seem urgent and new, even when faced by characters who seem temperamentally unsuited to say, or maybe even admit to themselves, what they want, much less seek it out.

That doesn’t even take into account other characters who push the story in one direction another, various sisters-in-laws and out-of-town uncles who have their moment. It’s a lot to keep straight, so much so that even a supporting character comments on how confusing it all is, a moment that feels a bit like Ozu and writing/drinking partner Kogo Noda offering the equivalent of a shrug. Sickness and death, however, ultimately give the story focus as the sprightliness of the first half gives way to the more reflective mood of the second, before a somber, knowing finale — and another unforgettable pillow shot, this one of a crematorium’s smoke stack and featuring a cameo from Ozu regular Chishū Ryū.

A staple of Ozu films dating back to the silent era, Ryū’s reduced role likely has something to do with the fact Ozu made The End of Summer for Toho,. his only film for the studio, That shift led to him working with a number of their contract players but not a total absence of familiar faces. Hara is an actress synonymous with Ozu’s work, thanks to the impact she made in classics like Late Spring and Tokyo Story. Did any other director understand Hara’s gifts as well, her ability to convey one emotion with a smile but another altogether with her eyes?

Here, her character mentions her age so often that Noriko has taken to fining her 100 yen whenever she calls herself old. Now in her forties, the widowed Akiko has limited opportunities to marry again — if she wants to. She tells Noriko she’s happy just raising her son on her own, and that may be true. Or it may be that the suitor presented to her, a man whose defining quality is a collection of clothing and art featuring cows, is kind of a drip. Either way, Akiko knows a closing window when she sees one.

Like Akiko, The End of Summer drops references to the passing of time, both personal and cultural, in nearly every scene. Akiko wears traditional clothes. Noriko is dressed in stylish ’60s Western fashions. Yuriko is even more fashion forward when she hits the town with a succession of towering American men. A pair of scenes take place in a bar not far from a neon sign that reads, in English, “New Japan.” One character, seemingly recalling a familiar saying, refers to the period between a death and the symbolic moment when the living move on from it as lasting “until the moss grows.” The film suggests we’re all living in that moment, in one way or another.

Ozu died in 1963, two years after the release of The End of Summer and not long after the death of his mother, with whom he lived until the end, often making films about marriage and the way it separates parents from their children. Hara retired 4, from film and public life in 1964 and died in 2014 at the age of 95. She developed a Garbo-like reputation, but both star and director were, in their own way, a mystery. Ozu revealed little of himself, demurring when asked about themes and methods.

Daniel Raim’s 2016 documentary In Search of Ozu attempts to peel some of this mystery back by speaking to those who knew Ozu and by looking at the objects he left behind: the truncated “crab’s legs” tripod he used to shoot his films, some handwritten scripts and storyboards, the teacups he made to serve as props. In it, Zen master Eon Asahina reflects on the meaning of the character of “mu,” or “nothingness,” carved on Ozu’s grave by Asahina’s grandfather, and what it can reveal about Ozu’s art. “There’s nothing superfluous in his films. They have a simplicity that reveals the essence of things.”

That word, “simplicity,” gets applied to Ozu a lot, but it feels slippery. Elsewhere in the documentary, Raim features notebooks filled with color-coding and symbols that only Ozu could decipher, a system laying out exactly what he wanted in each shot. It took a lot of work to achieve that much simplicity. Ozu's films are unassuming and consciously humble but they’re elusive, too. Ozu never tells viewers what to think. He offers scenes of characters sorting through how they feel and lets those watching them draw conclusions, if there are any to be found.

The End of Summer is available on DVD as part of the Criterion Collection’s Late Ozu box set and can be streamed on The Criterion Channel and Kanopy. In Search of Ozu is available on The Criterion Channel.

Next: Walking Tall Part 2 (1976)

Now this is the kind of thing I was glad to subscribe to The Reveal for!

I’m with you Keith on the whole “feeling like a poseur” thing. I’ve seen six Ozu films (and have the five Criterion blu’s on my shelf) and consider him to be one of the great directors, but then I think about how few I’ve really seen in the grand scheme of things.

Unfortunately can’t really comment on End of Summer, but I don’t think there’s a better director at establishing the homelife and culture of his country for his audiences than Ozu. I always think of An Autumn Afternoon and how it tackles the influence of Western culture on Japan after World War II.

This is the kind of thing that Yukio Mishima obsessed over and eventually killed himself to protest, but Ozu just kind of presents it as a fact of life that and the way that different generations might view this Westernization. It’s like every movie he makes is a gentle, modern version of The Leopard.

Great piece, Keith. It also makes me think of something I've been thinking about... a lot, lately! Which is, how the hell does one decide, in this era of Everything Always, on what to watch at any given moment? I'd be curious to hear other folks' perspectives on how they navigate this dilemma. Every time I log onto the Criterion Channel, I basically have a nervous breakdown contemplating the infinite number of masterpieces (and also interesting minor films) that I have to choose from.

One thing I've been thinking about doing is basically proceeding from the start of Criterion's chronological release history and filling in the gaps that way. I've also used random number generators for certain lists (like TSPDT's, on Letterboxd), and I've proceeded chronologically through directors' ooooooo-voirs. (Ooo-vruhs?) It's hard! The tyranny of choice! Etc!