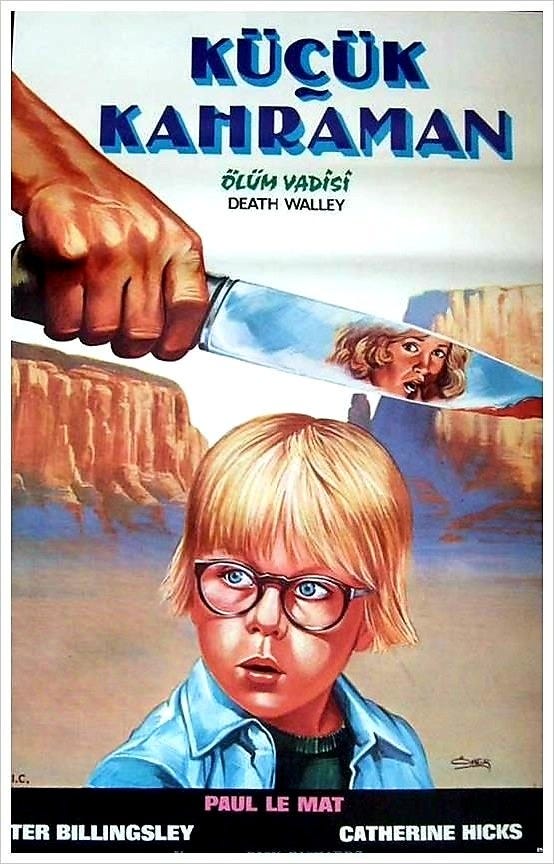

Minding the Gaps: ‘Death Valley’ (1982)

In which the quintessential late-'70s/early-'80s cute kid gets terrorized by a knife-wielding maniac.

Minding the Gaps is a recurring feature in which Keith Phipps watches and writes about a movie he’s never seen before as selected at random by the app he uses to catalog a DVD and Blu-ray collection accumulated over the course of the last 20+ years. It’s an attempt to fill in the gaps in his film knowledge while removing the horrifying burden of choice. This is the sixth entry.

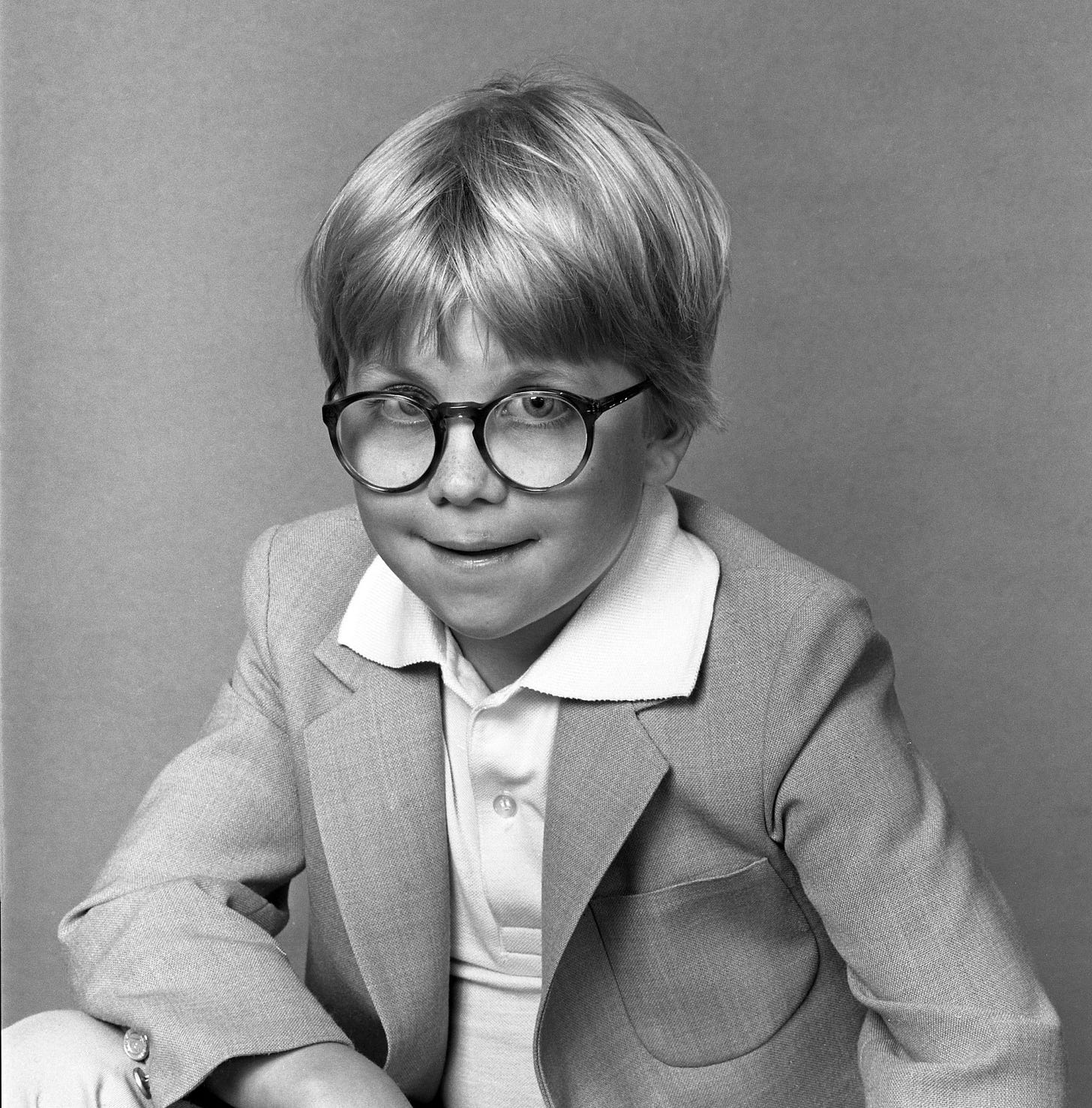

I can’t remember a time when Peter Billinglsey wasn’t in my life and neither, I suspect, can you. Billingsley is now best known as the star of A Christmas Story, Bob Clark’s adaptation of Jean Shepherd’s semi-autobiographical holiday memories of growing up in Hammond, Indiana, in the 1930s. A box office disappointment when it was released in the fall of 1983, it became a holiday fixture thanks to home video and, especially, endless airings on cable, including TNT’s habit of programming it 24/7 at Christmastime.

Shot when Billingsley was 11, A Christmas Story now looks less like a breakthrough for the young star than a culmination, a late work from a master made before moving on to other pursuits, as biology would soon necessitate leaving cute kid roles to others. It’s an end, not a beginning, but, in the years leading up to it, Billingsley was as unavoidable as Lee Horsley or Pac-Man fever. He was the commercial kid.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

Billingsley shot his first commercial as a toddler, an ad for Geritol starring Betty Buckley. Over 100 more appearances followed, including spots that cast him opposite Reggie Jackson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. If Billingsley had a signature role prior to the Red Ryder-maddened Ralphie Parker, it was Messy Marvin, the protagonist of a series of Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup spots that attempt to show that even the sloppiest child could easily make their own chocolate milk. For TV-raised kids roughly my age (which is also roughly Billingsley’s age), the elongated vowels of the Hershey narrator’s emphatic voiceover doubles as an auditory madeleine. (“His rooooom is a mess. His cloooothes are a mess…”) So, for that matter, does the image of a young Billingsley. If you turned on the television, Billingsley was there. Maybe he was selling roast beef sandwiches. Maybe he was serving as the youngest co-host of Real People alongside Fred Willard and Byron Allen. But, at any given moment, Billingsley was likely on television doing something.

It’s not hard to see why Billingsley became a big star in the ’70s and ’80s, or at least as big of a star as any child actor could making commercials (with the occasional film and TV gig on the side). He was cute without being cloying. He had a winning smile but deployed it sparingly and he never strained to be adorable. He just kind of was. His default demeanor was that of a boy carrying around as much worry as his little shoulders could bear. He was a natural, even if seeming natural was part of the act. If advertising is, at heart, about selling products to satisfy real or imagined needs, here was a kid who looked like he always needed something.

On the audio commentary to the R-rated slasher film 1982 film Death Valley, director Dick Richards describes Billingsley as “a young kid with a 40-year-old brain.” Couched in a description of how easy Billingsley was to work with and what a great and supportive family he had, Richard means that affectionately, but it also encapsulates much of what made Billingsley an appealing screen presence–and perhaps something of what allowed him to transition with rare ease from child star to a successful adult producer and director (though he still occasionally acts, he helmed Couples Retreat, shares a production company with Vince Vaughn, and produced several Jon Favreau films, including Iron Man ). Without A Christmas Story, however, all of that might have been forgotten. Commercial stardom starts expiring the moment ad campaigns end.

A perfectly solid, not particularly ambitious thriller, Death Valley would not have been Billingsley’s ticket to immortality in a Christmas Story-free universe. Still, the skills that made him a successful hawker of [insert the product of your choice here] serve him well playing Billy, a New York kid trying to adjust to leaving behind his tweedy dad (Edward Herrmann, perfectly cast) for a new life with his mom Sally (Catherine Hicks) in her hometown of Phoenix. That also means adjusting to life with Mike (Paul Le Mat), Sally’s cowboy hat-wearing childhood sweetheart-turned-post-divorce suitor. (A testament to Billingsley’s gifts: he convincingly plays a kid who looks like he’s never seen a cactus before, even though Phoenix was Billingsley’s own hometown.)

To bond, they take a vacation to Death Valley. This turns out to be a bad idea. Near a tacky ghost town tourist trap, Billy explores a seemingly empty RV — the site, unbeknownst to Billy, of a recent murder. He swipes a piece of frog-shaped jewelry from the scene; it’s the perfect crime, or might have been if Hal (the great Canadian character actor Stephen McHattie), a server at a greasy spoon they visit, didn’t notice it and realize it could tie him or someone close to him to some foul deeds.

Richards was himself no stranger to advertising. He worked as a photographer for Life magazine but rose to prominence in the Mad Men ad world of the 1960s before transitioning into feature films in the 1970s. As the director for the The Culpepper Cattle Co. and the Robert Mitchum-starring Raymond Chandler adaptation Farewell, My Lovely, he enjoyed some success. But while Richards’ contemporaries in the UK advertising scene, like Ridley Scott and Alan Parker, were defining the look of modern commercial filmmaking in the 1980s, Death Valley finds Richards working in a flat, functional, TV-movie-with-a-budget style.

It might sound odd to see Billingsley in such tough fare, but he fits in surprisingly well. That’s partly because Death Valley takes its time getting to Death Valley and the killing therein. Billy spends more time reluctantly getting to know Mike than in direct peril. But he does worry a lot, and few child actors could convey pained concern as well as Billingsley, whether he was evading serial killers or listening to his mom tell a scary story before offering her a LifeSaver.

So what, if anything, are these two advertising worlds separated by a generation selling here? Mostly a passably entertaining studio version of the down-and-dirty slasher films rolling out by the score in the early-’80s. The film doesn’t want for flashes of nudity and bloodletting — pity the poor babysitter lured away from Billy by the promise of sweets from the motel vending machine — but it's polite in the way it gets to such lurid material. Even the big twist revealing the killer’s secret isn’t particularly shocking. (I won’t spoil it, but it’s not exactly Michael [redacted] showing up wearing [redacted] at the end of [redacted].)

It ends more with a shrug than a jolt, despite the cool professionalism of everyone involved. And, if not for cultural archeologists like those who read and write film newsletters curious about the arcana of yesteryear, it would likely live on as an even fainter cultural memory than that juvenile slob Messy Marvin. Unlike Ralphie, of course, who’ll be shooting his eye out for the rest of my life, yours, and, it would seem, the lives of generations to come.

Next: Tunes of Glory (1960)

“It ends more with a shrug than a jolt, despite the cool professionalism of everyone involved. And, if not for cultural archeologists like those who read and write film newsletters curious about the arcana of yesteryear, it would likely live on as an even fainter cultural memory than that juvenile slob Messy Marvin.”

It’s not like 40 years is that long ago but the stuff like this that falls through the cracks can still, uh, reveal things of interest. If nothing else, it shows where the cracks are. Keep these excavations coming, this is an excellent piece and just really good writing. Also, I am very much interested in seeing The Dirt Bike Kid vs. Pontypool now.

Lee Horsley! There's a name that doesn't come up enough. PARADISE was required viewing in my house growing up, no matter what night of the week they switched it to.