'Light Sleeper': The ghostly souls of Paul Schrader

In his 1992 indie drama with Willem Dafoe, Schrader reworked 'Taxi Driver' into another urban tale of alienation and violence. But with a twist.

Two films, two journal entries.

“June 8th. My life has taken another turn again. The days can go on with regularity over and over, one day indistinguishable from the next. A long continuous chain. Then suddenly, there is a change.”

“I feel my life turning. All it needed was a direction. You drift from day to day. Years go by. Then a change comes. I am able to change. I can be a good person. What a strange thing to happen halfway through your life. What luck.”

The first is from Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, as he resolves to carry out an assassination plot against a political candidate—partly out of a spurned effort to woo a pretty campaign worker, partly out of a deranged and hardening sense of purpose. The second is from John LeTour in Light Sleeper as he reels from his own romantic travails and winds up setting himself on his own inexorable path to violence. Both are from the desk of screenwriter Paul Schrader, which we can only assume on the evidence is an austere wooden desk with a collection of pencil-scrawled journals. At the time, 1992’s Light Sleeper was thought of as the third in Schrader’s “God’s lonely man” trilogy, following 1976’s Taxi Driver, which he scripted for Martin Scorsese, and 1980’s American Gigolo, his third film as a director. He’s returned to the character recently in a burst of provocative dramas that could form a trilogy of its own: 2017’s First Reformed, 2021’s The Card Counter, and his new feature, The Master Gardener.

With all due deference to Schrader’s hero Robert Bresson, one of the subjects of his Transcendentalism In Film book and the direct inspiration for these films, Schrader’s obsession with quiet, disturbed, alienated men has long felt uniquely personal. He has described writing Taxi Driver in just ten days—“it sprang from my head like an animal,” he said—and the material still feels raw and emotionally on-the-surface, as if he didn’t care to process or aestheticize it. One of the most upsetting aspects of Taxi Driver is that Schrader and Scorsese don’t put much distance between themselves and a man who’s plainly a racist, violent sociopath, because his loneliness and pain are so identifiable. The “God’s lonely man” characters in subsequent films may be driven to extremes themselves, but the common thread is the feeling, expressed in Travis Bickle and John LeTour’s journal entries, of lives and souls that are dangerously adrift.

Of all of Schrader’s films, Light Sleeper feels like the one most strongly connected to Taxi Driver, though it replaces the seductive craft of Scorsese’s urban nightmare with a moodier tone that’s more existential—and, true to its title, perhaps a bit somnambulant. Though American Gigolo had been a hit, due mainly to producer Jerry Bruckheimer and star Richard Gere offering their own distinct commercial appeals, Light Sleeper is more in line with a director who has rarely been in step with modern audiences. It follows the basic arc of Taxi Driver, as an urban loner seeks redemption through love, but ultimately sets himself on a path to violence, “saving” a woman in the process. Yet Schrader’s approach to the crime drama is remarkably introspective, starting with a high-end drug dealer who moves through the scene like a ghost and a supplier who’d rather be selling cosmetics. Standard genre fare this is not.

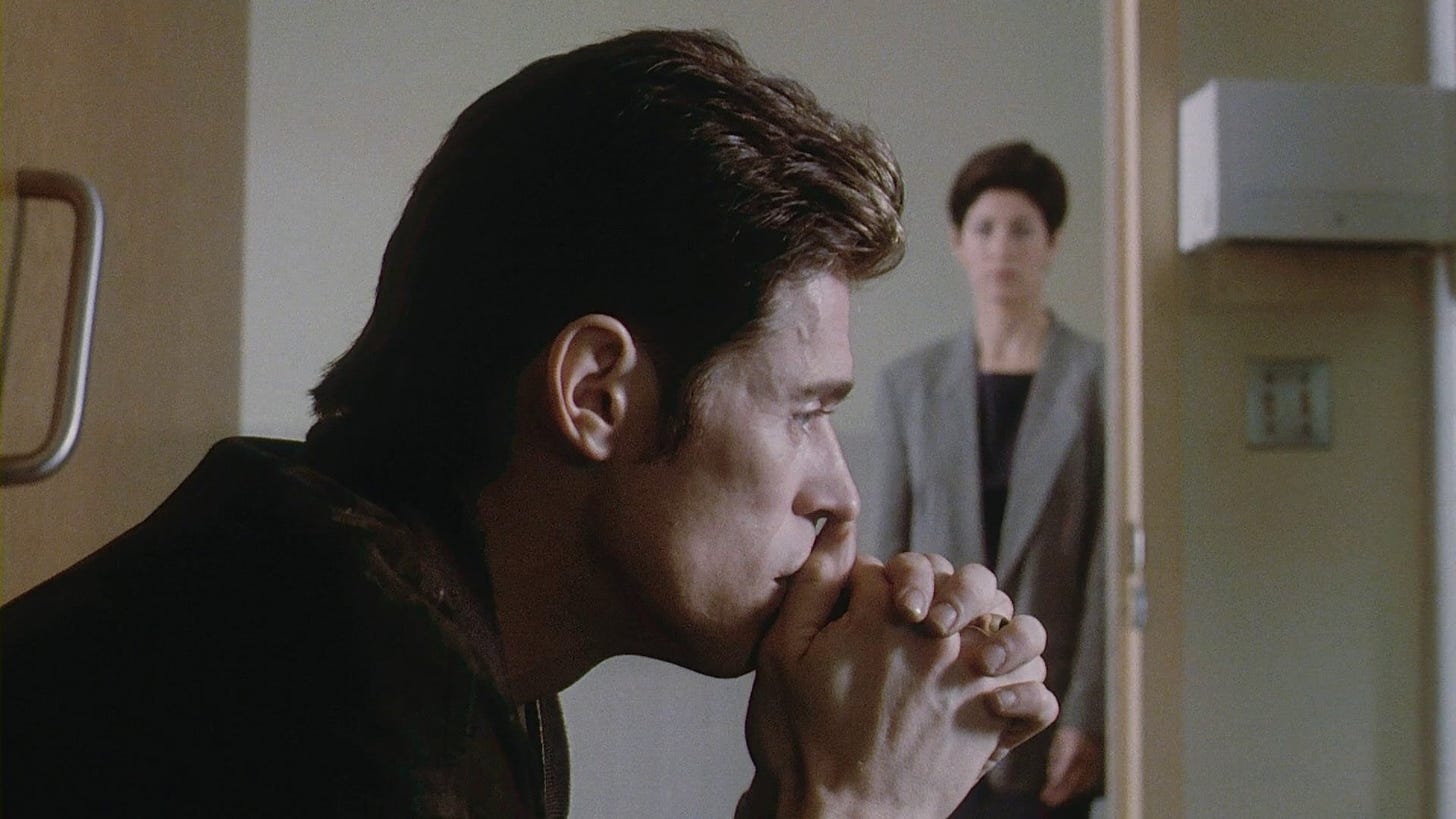

From the opening shots of steam rising up from a hell just below the cobblestone streets, Schrader and his ace cinematographer, Ed Lachman, do little to discourage the Taxi Driver connection. To extend the metaphor further, Light Sleeper takes place during a garbage strike that suggests a fetid stench in the air that grows riper as the bags continue to pile up in the background. That doesn’t stop John LeTour from walking around the city endlessly, as he tries to fill the immense time between drug deliveries and the small handful of hours he gets to sleep each night. He’s played by Willem Dafoe, who has the right hollow face for an ex-addict with a permanent redness around the eyes. Perhaps it’s a rehabber’s instinct to take things one day at a time, but John doesn’t have a plan for tomorrow, even if tomorrow has a plan for him.

In sharp contrast to Travis Bickle, whose willingness to drive anybody anywhere in New York City fed his vile impression of it like logs to the flame, John travels only in tonier circles, serving cocaine and prescription highs to clients who don’t want to deal with street dealers. His deliveries are chauffeured, discreetly palmed off in restaurants and clubs or straight to residences that are usually well-appointed—or would be, if it weren’t obvious that the buyer had a serious drug problem. His boss Ann (Susan Sarandon) has the necessary toughness for the job, but she isn’t surrounded by henchmen and refuses to allow guns of any kind to be present on either side of a deal. It’s as close to a safe operation as these things get: too small to attract much attention, from the authorities or from rival dealers, and serving customers who are always good for the money.

Yet for John, there are signs of turbulence that he’s unprepared to manage. For one, Ann seems intent on following through on her promise to step away from the business and he hasn’t been saving his money, despite living in an apartment no more glamorous than Travis Bickle’s. On top of that, the murder of a wealthy 19-year-old with cocaine in her system has the police asking questions about his shady German client, Tis Brüg (Victor Garber, in a ridiculous performance). But a deeper catastrophe presents itself when John bumps into Marianne (Dana Delany), an ex-wife and former user who’s cleaned up in the few years since their relationship ended. John catches Marianne in a vulnerable place, with her mother in the hospital with a terminal illness, but his hopes to rekindle their old flame loosens her unsteady hold on her own sobriety.

Unlike Travis, John is not a violent person by nature. He doesn't obsess about the outside world, either, but rather walks through the steam and the filth as if he were an apparition. Yet the walls close in on him in a similar way. His choices narrow until the only path is catharsis and redemption through violence. He correctly suspects that Tis wants him dead, so he prepares for it just like Travis, by picking up a gun on the black market and stepping into a situation that he doesn’t expect to survive. He wonders if he deserves to survive, after everything that’s happened to Marianne and the poison that he distributes for a living, which he can rationalize to some extent—in one scene, he refuses to sell to a strung-out client and even calls the man’s brother to intervene—but he’s not exactly adding value to society. What is his actual purpose here?

Yet the door is not always closed for a Schrader character. In Taxi Driver, Travis’ redemption is laced with irony. The fact that he killed a pimp instead of a politician makes him a hero in the public eye, even though he was a ticking time bomb that, in the end, seems to reset itself. Light Sleeper ends almost exactly as The Card Counter would years later, with John having found some measure of peace and connection despite being confined to a prison cell. It is not clear what future John might have five years later, when he’s finally free. His sterling reputation as a drug dealer will not serve him that well on a résumé. But there’s a feeling of spiritual sobriety that carries Light Sleeper to the sort of transcendent ending that Schrader so admired in Bresson. John has passed through this long, agonizing night of the soul. He’s relieved of guilt. He can finally—and perhaps literally, in his journal—turn a new page.

One of those movies that I'm going to have to cave and buy digitally one of these days. Keep waiting for a US Blu, but no luck...

Woah I was just catching up on old Next Picture Shows and just listened to the Card Counter episode.