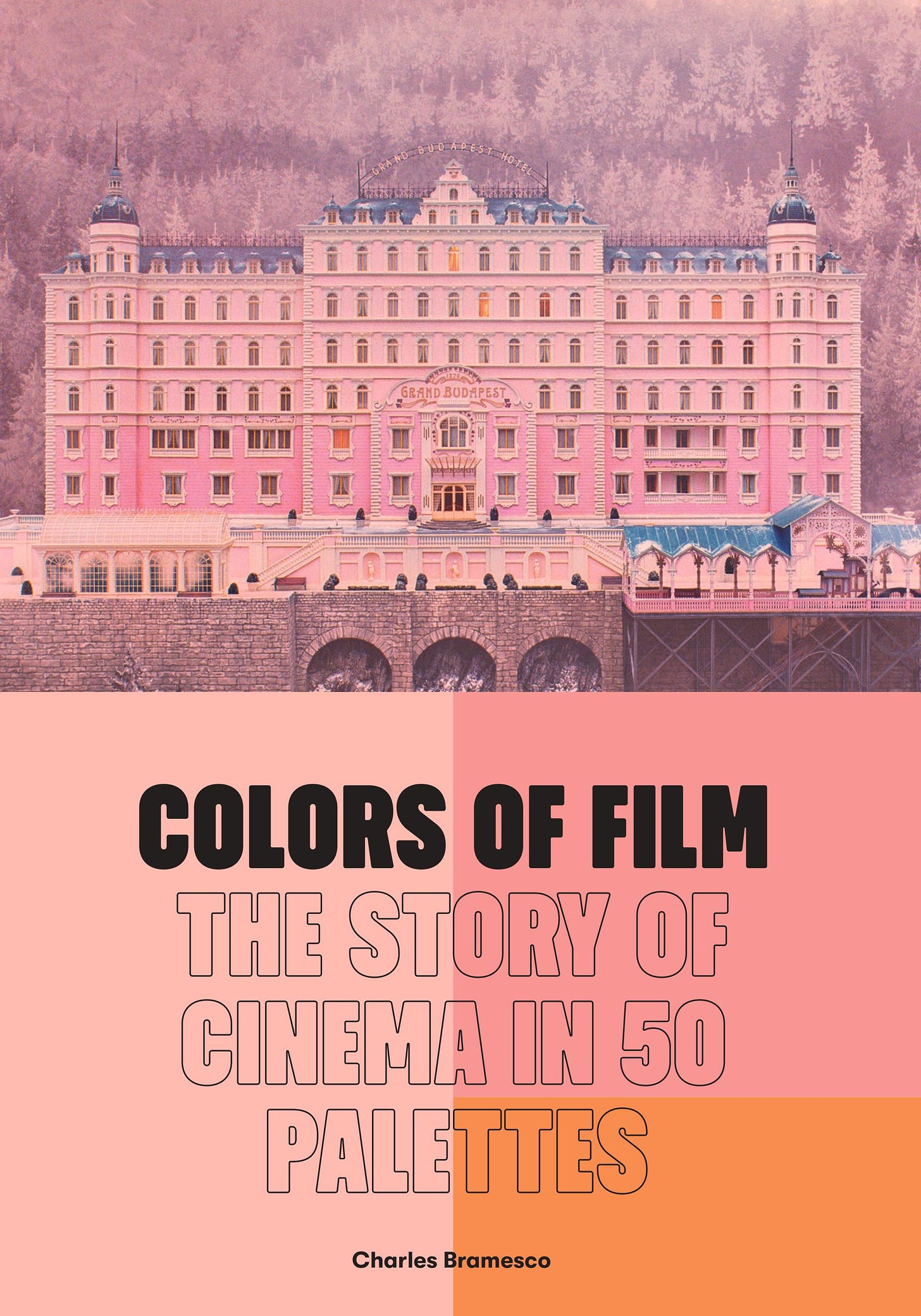

Interview: 'Colors of Film: The Story of Cinema in 50 Palettes' Author Charles Bramesco

Bramesco's new book traces the history of color movies using fifty remarkable examples that span color filmmaking's low-tech origins through the digital age.

How do you tell the story of color movies? For critic Charles Bramesco, the answer was pretty simple: tell it via movies and colors. Bramesco’s new book Colors of Film: The Story of Cinema in 50 Palettes (published by Frances Lincoln) surveys the history of color filmmaking from the hand-painted prints of Georges Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon and tinted images of Intolerance to the digitally created landscapes of Black Panther and rich hues of Lovers Rock. Collectively, the fifty selected films double as a timeline for expanding artistic possibilities, changing tastes, and evolving technology, but it shouldn’t be mistaken for a straightforward story of progress. No story that sees Technicolor fall out of use as it became economically prohibitive, for instance, ever could, and the book creates a sense that every new possibility and technical leap forward requires letting past wonders fall by the wayside. As his book began to arrive in bookstores, Bramesco (full disclosure, a longtime friend of The Reveal) spoke to us about how color film’s bright past, dim present, and possible future.

What was the most surprising thing that you learned in researching and writing Colors of Film?

What I really learned is that I have so little technical knowledge of how the moving image is created! I just spent a day Googling and trying to wrap my head around the way a movie camera captures visual information and prints it onto a filmstrip. I mean, I understood what Two-Strip Technicolor and Three-Strip Technicolor were, and the layering of colors that way. But I did not actually know about intake lenses, and I did not know about the filtering of the different colors through prisms and the way that works. I tried to get deeper into the technical nitty-gritty than I had ever gotten before. And I am not a scientific-minded person, so that was a very unfamiliar territory for me.

How did you arrive at the book’s fifty films?

The idea was always to have fifty because I think with that number you can cover a lot of breadth. That was kind of what I was going for, to be just as well-rounded as possible in terms of chronology, in terms of scale of production, geographically. I wanted to speak to as many different big corners of cinema as I possibly could. So within those fifty, it kind of starts with a lot of very canonized picks. But then as we get into the '60s and '70s and world cinema starts developing and independent cinema starts developing, I got to pick more off-the-beaten-path things.

I knew, for instance, I wanted to touch on Indian cinema. I knew I wanted to touch on African cinema. I knew I wanted to touch on horror. That was a big one for me. And the publisher, they were very cool. I sent them my list of fifty and they basically said, “Looks good.” Which I was really surprised about, because they were cool with God Told Me To, which I think has a lot to say on the matter, but is not the first movie people would think of in terms of colorful movies. But the way it uses color to kind of delineate between the genres that it hops between is really clever. And they were very open-minded about that.

I was going to say that I think one theme emerges in this book is that new opportunities for color are found as much in genre films as in the canonical films. I was surprised and delighted to see Herschel Gordon Lewis represented in this book.

One of the ways I thought about these fifty was as a large curriculum for a course. And I think within that, you can pick out groups of two, or three, or maybe four movies that would be their own lesson plans. So in terms of horror, the big arc that you see there goes from… In section two, there is Color Me Blood Red. And then in the fourth section is Saw II. And the way that the color of blood changes, I think, says a lot about how the tenor of horror films changed. That in the '60s there was a kind of antic sensibility to these Herschel Gordon Lewis movies. They're insanely violent, but they also have a light tone. They're trying to have fun. They’re knowing about their own hokiness. And then we get to something like Saw II, which also, I think, takes a lot of pleasure in its sick little games, but it tries to be more hardcore. It's much more grizzly, more just it's got dark rings around its eyes, that movie.

That seems like an instance of the color changing everything about a movie. Was that sort of the sense you got writing this book, not just about horror but about other types of films?

This totally rewired the way I watch every movie, even the movies that I would not have picked for this book. Every single thing I watch now, I see the way color is used. Even in ways where it is not so conspicuous, where it's not as easy to pluck something out and analyze it and assign its significance. Every movie has a color palette that's been thought through and is supposed to correspond to the subject matter, and then the tone that's being evoked. It’s like editing, where when you don't notice it, you know it's being done well. There’s so much work that goes into this that I'd never considered before and that I like being able to consider now.

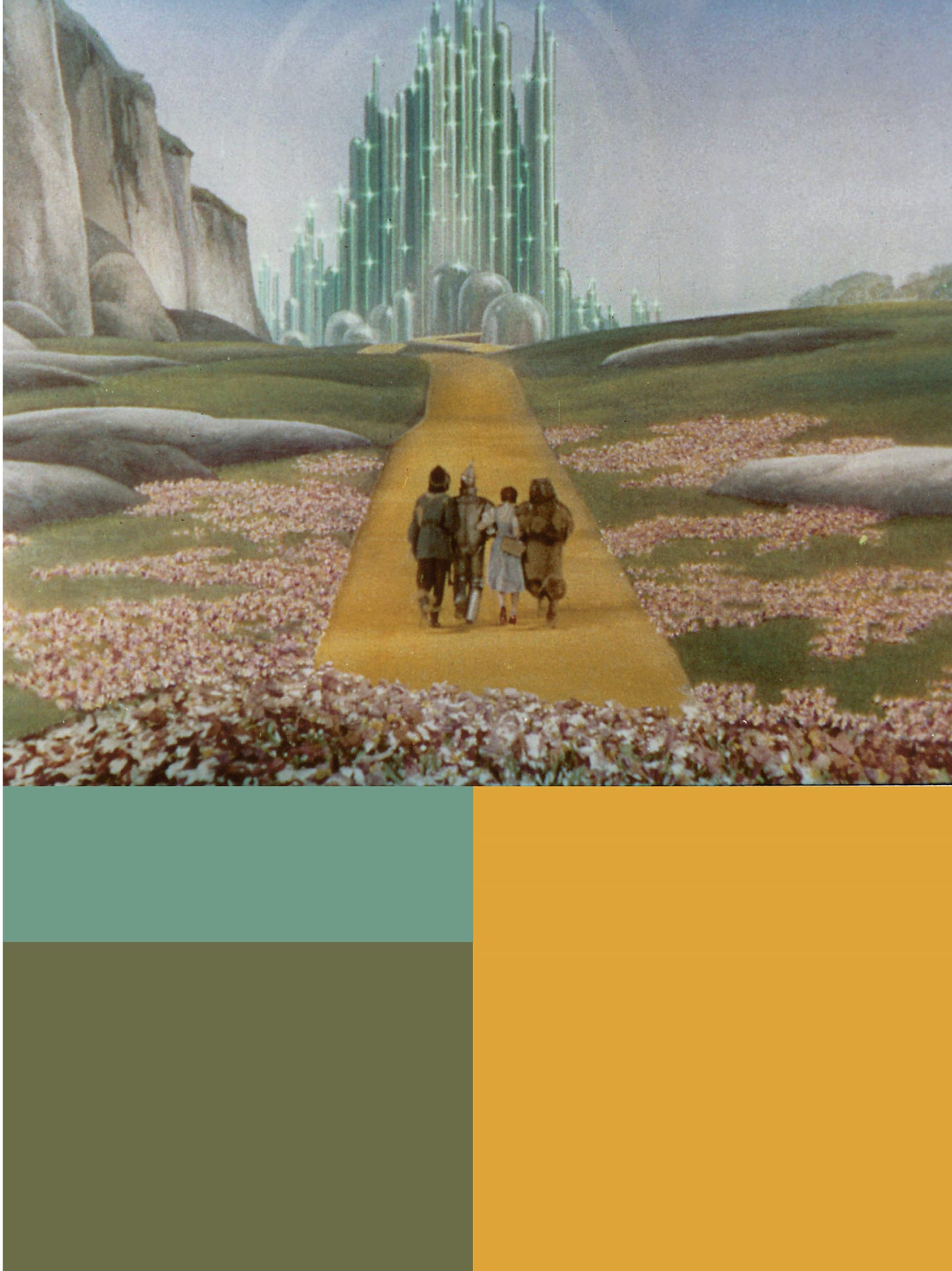

Were there some films that you just knew, going in, you had to include? I can’t imagine a book like this without, say, The Wizard of Oz.

When I was first talking with the publisher and putting together the pitch, they wanted one sample entry, and that was the first one I thought of. That seemed like such an essential piece of this. And especially for me personally, The Wizard of Oz is my favorite movie of all time. It's one of the first that I can remember watching and being just totally blown away by. That was absolutely a must for me. And I knew digital cinema would be a really big part of the end.

One of the ones that I got excited about earliest was Speed Racer, which is a movie I love a lot. And just every single time I watch it, I'm amazed at how they got it to look. I'm pretty excited this summer for Barbie, because it seems like visually they're trying to do a lot of the same hyperreality things. It's my understanding that they've got all these new innovative techniques for shooting color and for color timing. And so I think that should be fun in that same vein.

I knew I wanted to do Suspiria. That was right at the front of my mind because the way the movie uses color is so emotive. But then once I started researching, I found it also had a much more direct significance to this project. It's one of the last Technicolor movies made in Italy, if not the last. In addition to everything it's doing historically, you can sort of use that as a fence post to mark between periods of time.

It's sort of a new way of thinking about Suspiria, as kind of a farewell to this way of filmmaking.

If you look at Argento's movies after that one, they start to look very different. Even as he would maintain a lot of his style and a lot of the ways that he wanted to use color, the end product just started to look different because the materials available to him just weren't there anymore. It's pretty wild.

A narrative that emerges over the course of this book in which art and technology kind of push each other forward, but so do films’ commercial considerations. Of those three, is there one force you feel is stronger than the others in the story of color on film?

I do think that in the grand rocks, paper, scissors of this, the winning one is usually money because that’s the one where there is the least wiggle room. I think with technology, people are very innovative. You look at James Cameron: he invents the technology to make the movies look the way that he wants before he starts making a movie. There are limitations to technology, and of course there are limitations to human creativity. But I think if you look at the way things have played out, when people have stopped using a type of technology, it is almost always because it's become prohibitively expensive.

And that's the thing about movies: It's not like painting. You can't do it in your bedroom. It requires a lot of people and a lot of money, especially if you want… All of the movies in the book are pretty visually spectacular, and to achieve that you have to be able to work at a certain scale of the industry. These aren't really things that you can’t do in your town with your buddies. So people are beholden to money, but I think the good directors—and I think the book gets into a lot of this—figure out how to work within these systems. The history of art is figuring out how to make these things work for you.

You make a good case for there being really terrific use of color in every era, but do you have a favorite?

Definitely. The MGM musicals, I could have done a book that was just 50 of those. I did kind of double up, because you have both The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain. But The Wizard of Oz isn't really like a Freed Unit, full musical kind of musical. If you watch any one of those, even the ones that aren't that good, they're just eye-poppingly beautiful, and watching them makes me very emotional. At the Museum of the Moving Image last weekend we showed Singin' in the Rain. And I went to go see it, and I, much like Diego Calva at the end of the major motion picture Babylon, found myself just overcome with emotion, weeping.

And for much the same reason: that you see these things and you know that you will never be able to get these back. He watches that as his own memories and the things he's lost in his life, but I think if you're a modern viewer, and especially someone who has an emotional connection to older movies, you watch this and realize we do not have the means to make them like this anymore. It's not that they don't make them like they used to: we cannot do this. We don't have the cameras, we don't have the film. We just can't make things that look like that. It's very melancholy, but it's so beautiful.

Along those lines, you cover The Aviator, which is kind of an attempt to, for one of a better word, fake the look of older films. Can you achieve that look digitally or is there just something about the chemical process of the film itself that you're just never going to be able to recreate?

I think The Aviator is a good case study. And first off, I mean, if you're going to do something like this, it helps to literally be Martin's Scorsese.

Sure.

I think that would be in your favor, but the way he does this kind of imitation Two-Strip Technicolor, it does not actually look like it did back in the day. The blues and reds are kind of in the same color, but the finished image is so sharp and digital because it had to be because that was the way he was able to do those. I think Scorsese almost intends that more as a wink. Not so much literally trying to emulate that look, but showing to the people who are aware of it, that he's aware of it as well, that it's sort of a nod more than a literal trying to emulate that.

I don't know… I mean, I always get very annoyed when people use digital technology to insert crackles and pops into things, or to make it look like it's a beat up movie from the '70s. I did not care for Skinamarink, which does so much of this. It's a digitally thought movie. And [director Kyle Edward Bell] says that he grained it up in post, where I was like, yeah, that's one way to do that. You could have gone through the work of purchasing a camera and actually doing this, and it would've looked right.

You praise Black Panther, but kind of couch it in sort of some less than flattering commentary about the way other Marvel films look. I know I see that kind of muddy, dingy look spreading elsewhere. It's part of what bugged me about All Quiet on the Western Front so much. Are you optimistic about the future of color? Do you feel like the pendulum's going to swing back at some point?

I am not super optimistic. Black Panther's presence in the book, as much as I do think I like that movie a lot, its presence is there to point to the Goofuses to its Gallant. I do think the big main offenders are the Marvel movies, and we're starting to see that seep out. I just saw Shazam!: Fury of the Gods, which has that exact same desaturated, totally shadowless, we’ll-just-fix-it-all-in-post-and-then-never-actually-get-around-to-fixing-it kind of look.

We see that a lot in action movies, increasingly. It started, I think, with the superheroes, and now it's leaked out into other IPs, or franchises, and Netflix. My knowledge of this isn't comprehensive, but they have these dictates about house style that they give to directors that are working on their movies because they want to optimize their content to be watched on laptop screens, TVs, and phones. I would like to imagine that maybe things will change, but it doesn't seem like studios are moving toward committing to excellence over commercial prospects and maybe are going in the other direction. I don't see those two things as mutually exclusive. I think there's a lot of money to be made from having good movies and releasing them where people can see them.

Have there been any films released since you finished the book you wished you could include?

I mentioned Babylon, which would be such a good one. As you may recall, at the end, after they do the crazy montage that ends with Avatar, it dissolves back into colored dye, which is one of the big ideas of the book that when you reduce film to its absolute component parts, it turns back into color. And that is how the movie ends, which I found really clever and moving.

This sounds like a very cool book, which I will put on my birthday wishlist. I share Bramesco’s annoyance with the digital pops and crackles of Skinamarink. In fact, they were so cheaply done that you could see the static pattern repeating every few seconds, which I found incredibly annoying and distracting. Once I noticed this, I couldn’t see anything else.

This is wonderful. I am totally going to surprise my wife with this book, she'll eat it up.