Elvis: The ’69 Comedown

Elvis Presley cemented his '68 comeback with some of the best music he ever recorded. His attempt to reboot his film career during that period met a different fate.

In June 1968, Elvis Presley recorded Singer Presents… Elvis, a television special sponsored by the Singer Corporation. Now more commonly known as the “’68 Comeback,” the special would give the world its first chance to see Presley performing live in seven years, looking back to the past by reuniting him with the surviving members of his original band, and suggesting a possible way forward via well-chosen new songs and covers that allowed this complex, gifted performer to channel grown-up emotions and prove he’s more than a figure of the past. These included the special’s climactic selection, a stirring performance of “If I Can Dream,” a new protest song (if one filled with broad, vague phrases), and a number unlike any he’d recorded before. The following month Elvis flew to Arizona to appear in Charro, a western he hoped would do the same for his film career.

Only one worked out as planned.

By the time Elvis aired on December 3, 1968, it played as both revelation and confirmation. Even before TV viewers laid eyes on Elvis wearing a no-nonsense black leather jumpsuit, the “If I Can Dream” single (a hit after a string of disappointments) and the special’s soundtrack album, both released before its December air date, made clear something was going on with Elvis. He’d spent the years leading up to the special appearing in an increasingly formulaic string of musical comedies built around his persona and crafted to allow room for enough new songs to fill out a soundtrack album.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

The work was profitable and the process could be repeated at the rate of three movies a year, and Presley’s manager Tom Parker saw no reason to disrupt it. In time, his client felt otherwise and, rejuvenated by the process of recording the Elvis special, told producer Steve Binder “I’ll never sing another song that I don’t believe in. I’m never going to make another movie that I don't believe in.”

Elvis wanted something new from his music, and listeners wanted it too. In 1969, they got it in abundance. Opting to stay in his hometown of Memphis and work with producer Chips Moman at his American Sound Studios, Elvis recorded some of the best music of his career, a selection of songs that extended the social consciousness of “If I Can Dream” via “In the Ghetto” and found him grappling with rich, adult emotions unimagined in his ‘50s hits across tracks like “True Love Travels on a Gravel Road” and “Suspicious Minds.” His 1969 recordings truly sound like the work of someone committed to never singing a song he didn’t believe in again.

As those songs rolled out, however, moviegoers could be forgiven a sense of cognitive dissonance. On the radio: an Elvis successfully finding his footing in a changing world. On screen: an Elvis struggling to do the same. But he was trying. In Baz Luhrmann’s recent film Elvis, Presley (Austin Butler) expresses a sincere desire to be a respected actor, unaware that his movies would, in time, be treated as a sideline to his music, a desire the real-life Presley shared but never realized. But he was often better in movies than he would be given credit for, even if he never let viewers forget they were watching Elvis Presley. Writing of his film work a few years ago, Sheila O’Malley observed:

“Elvis was a persona actor. If you hold Presley up against Laurence Olivier or Claude Rains, then it doesn’t even seem like they are in the same profession. But it is the same profession. Presley had many natural gifts and he knew how to use them. He was dazzling to look at. He didn’t take himself too seriously. He had a gift for slapstick comedy (he does a pratfall in 1965’s Tickle Me rivaling the one Cary Grant does in the music room in The Awful Truth). Most importantly, he operated from a place of generosity. And generosity like that cannot be manufactured. Audiences feel it.”

Those gifts usually ended up serving films like Roustabout and Clambake, almost assuring they’d be overlooked, especially as “Elvis movie” became synonymous with “drive-in fluff.”

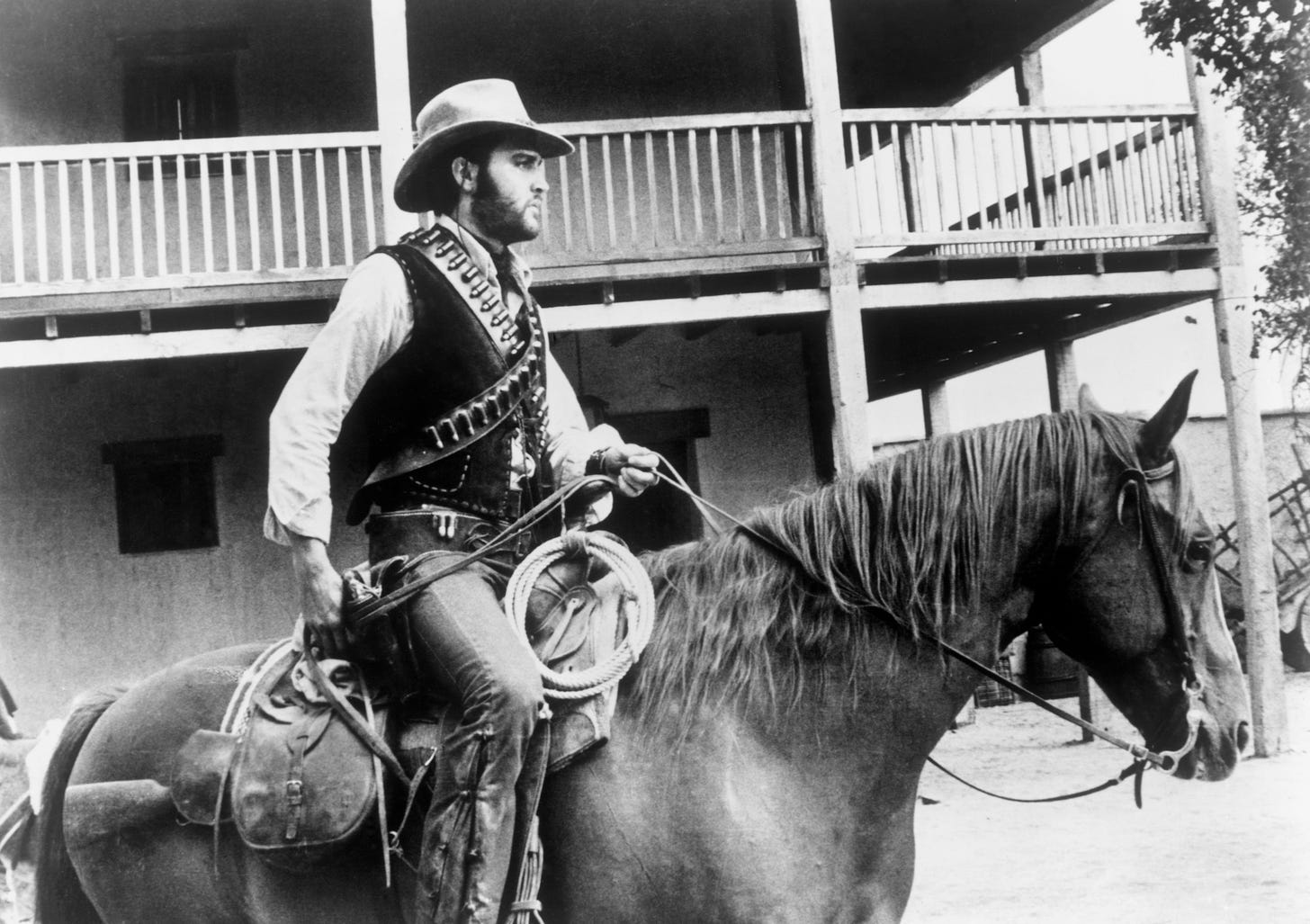

Elvis hoped the films he made after shooting the comeback special would change that and, initially at least, Charro looked like it might offer as dramatic a break from the past as the comeback special. It was conceived as a gritty, revisionist western in the spaghetti western mold, with the lead originally offered to Clint Eastwood. Unfortunately, the finished product plays like the sort of movie that, well, Eastwood would turn down.

Presley plays Jess Wade, a former outlaw trying to walk the straight-and-narrow path only to get drawn back into the criminal life by his old gang, who draw him into a scheme involving a stolen, gold-plated cannon of historical significance. The gang sets Wade up as the true villain by branding him to match the description of one of the actual perpetrators, who had suffered a bullet wound to the neck.

It’s a brutal scene, one in which Elvis, an icon with a carefully managed image, is humiliated and laid low (and one made all the more poignant knowing what we know now about his off-screen struggles and career sidetracked and squelched by those without his best personal interests in mind). But it’s also the only moment when Charro comes close to pushing its star into challenging territory. The film is more serious in tone than, say, It Happened at the World’s Fair and limits Presley’s musical contributions to the opening credits while letting him wear a scruffy beard. But it’s also one of many roles in which Presley plays a misunderstood rebel who’s really not a bad guy at all once you get to know him, almost as if any movie in which Elvis appeared must, like a plant bending toward sunlight, move in the direction of an “Elvis movie.”

It wasn’t supposed to be that way. In Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley, the second of Peter Guralnick’s indispensable two-part Presley biography, Guralnick writes that Presley arrived to find the screenplay “bowdlerized past the point of recognition. The opening scene, which had originally included three ladies of the night not only baring their breasts but pulling their dresses up […] became a standard barroom confrontation.” Still, Elvis does the best he can under the circumstances, playing Wade as a man who truly wants to do the right thing before it’s too late. He’s good, or at least as good as the movie allows him to be.

It’s hard to blame Elvis for this, however. Charro bears the flat lighting and half-hearted production design of the TV westerns where director Charles Marquis Warren frequently worked. In fact, the critics who bothered to review the movie largely didn’t blame Elvis. “Almost everything about this threadbare western is cheap-looking and phony except Elvis himself,” Kevin Thomas wrote in the Los Angeles Times, continuing to praise his “commendable, convincing performance.” In a career shaped by missed opportunities—in movies but also in music—Charro is one of the biggest misses of all. Elvis might have believed in the movies he made after his comeback (at least at first), but the movies didn’t believe in him.

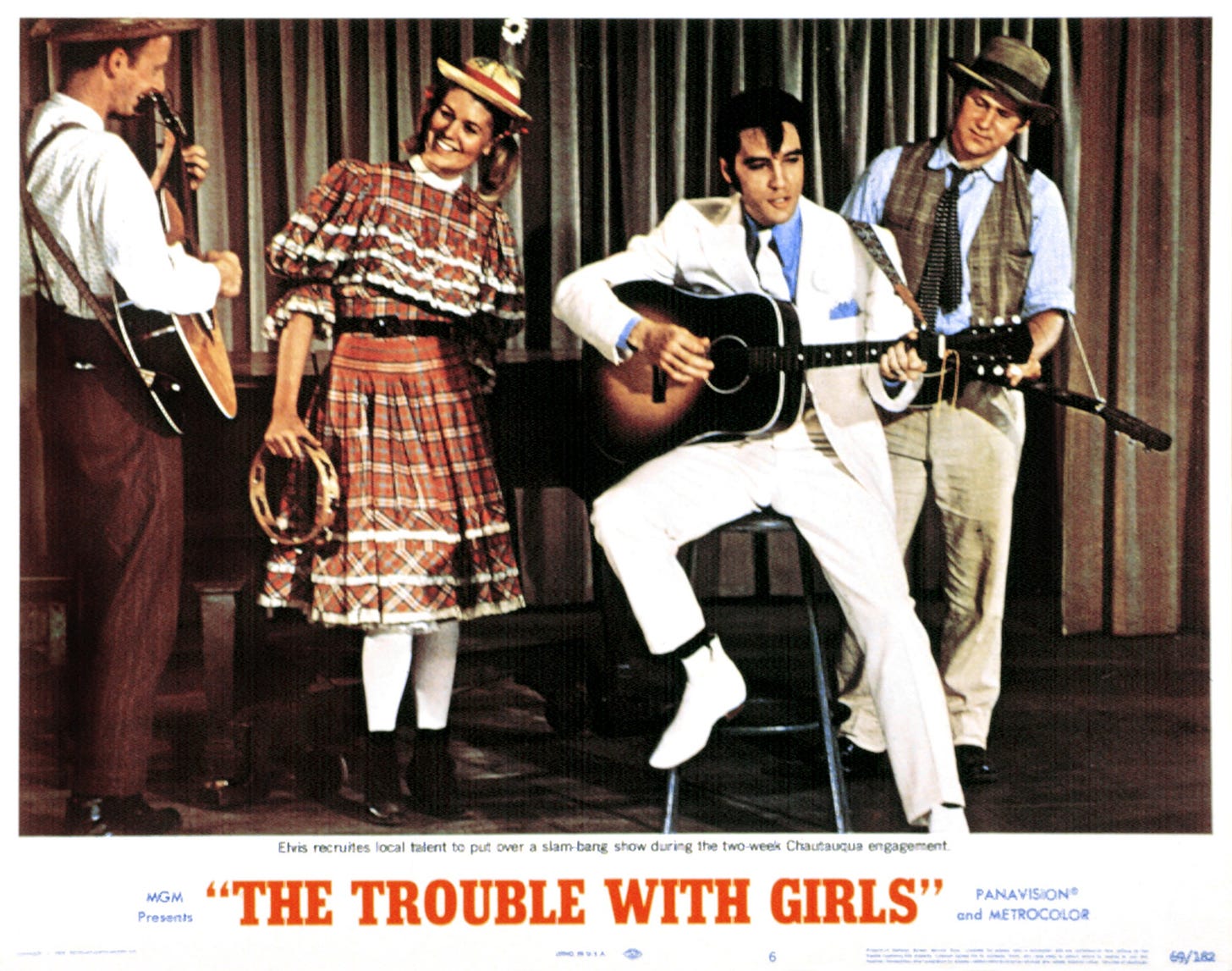

He’d finish out his acting career with two more misses, limp efforts that arrived in theaters as his music revealed a renewed sense of vitality, Both had glimmers of ambition to be more. Originally titled Chautauqua, The Trouble With Girls (full title: The Trouble with Girls (and How to Get into It) casts Elvis as the shady(ish) manager of a Chautauqua, a type of traveling, ostensibly educational fair that mixed lectures with entertainment popular at the end of the 19th and early decades of the 20th centuries. The film touches on labor issues, sexual exploitation, and even murder—but only briefly. It’s a mostly dire comedy about the quaint olden days livened up by a fun Vincent Price cameo and Presley’s performance of “Clean Up Your Own Backyard,” one his grittier soundtrack songs.

The Trouble with Girls was Presley’s 30th film as an actor. Change of Habit, his 31st would be his last. Co-starring Mary Tyler Moore (post-The Dick Van Dyke Show, pre-The Mary Tyler Moore Show), it’s—in concept at least—an attempt to extend Presley’s newfound (if controversy-averse) social consciousness to the big screen. Presley plays John Carpenter*, an inner city doctor determined to improve conditions in a troubled neighborhood. To that end, he teams up with a trio of nuns led by Moore. The twist: to better fit in, the nuns have decided to go undercover by discarding their habits (hence the title). Liberal do-gooding (complete with an unflattering depiction of some Black militants), awkward sexual tension, and the truly questionable treatment of an autistic child** follow.

Once again, an Elvis musical performance, an “impromptu” rendition of “Rubberneckin’,” a product of the Chips Moman/American Sound Studio sessions, provides the only real highlight. The trailer promised “a different Elvis Presley!” but critics weren’t fooled. “Nothing’s really changed,” Stanley Eichelbaum wrote in the San Francisco Examiner, going on to call it “straight, standard TV drivel.” Audiences seemed to agree. Released in November of 1969, its performance seemed to confirm that Elvis had no future as an actor.

But did that matter when Elvis, in the ways that really mattered, was back and better than ever? (The hype may have faded, but time has made the recordings he made post-comeback sound as towering as his breakthrough work.) Sadly, in some respects Elvis’ ’69 films serve as harbingers for what would follow. You can hear a renewed investment in Presley’s 1969 recordings and see it in footage of the early Las Vegas shows captured in the 1970 documentary Elvis: That’s the Way It Is. But the way Presley goes from pushing himself in Charro to cruising through The Trouble with Girls to mostly checking out of Change of Habit, mirrors the rest of his career, a long, slow fade to silence.

There’d be glimmers of brilliance, like the great 1971 album Elvis Country and in recordings that could still throw out sparks to the end of Presley’s life. (“Moody Blue,” the last single released in Presley’s lifetime, is, as the kids say, a banger.) But they’d be surrounded by unhinged live performances, dreadful stuff like “Raised on Rock,” and a worrying sense that he was trapped in a downward spiral of addiction and isolation seemingly confirmed by the tell-all Elvis: What Happened? published the year of his death. Maybe, like a musical number livening up an otherwise dull movie, the comeback was just a glorious, brief interruption before the credits rolled on an ending written long before.

* Coincidentally, director John Carpenter would later go on to direct the 1979 TV biopic Elvis. What’s more, Presley would occasionally use “John Carpenter” as a pseudonym when checking into hotels in the years after Change of Habit’s release.

** Soon-to-be stripped of his license child psychologist Robert Zaslow, who championed the now discredited “rage reduction” and “attachment therapy” approaches served as a consultant for one scene.

So what are the good Elvis movies? I remember loving Jailhouse rock scene as a kid. But other than that I’ve never dive into his catalog of films.