Dialogue: Sundance '92, Pt. 2 — Truth, Fiction, and the Changing Face of Documentary Films

Our revisit of the 1992 Sundance Film Festival continues with looks at 'Brother’s Keeper,' 'Incident at Oglala,' and 'A Brief History of Time.'

Over a three-week span, we’re discussing films from “Sundance Class of ‘92: The Year Indie Exploded,” a series currently featured on the Criterion Channel. Last week we covered the fest’s place in the emergence of New Queer Cinema. This week, we’re talking about the ‘92 fest’s documentaries, specifically Brother’s Keeper, Incident at Oglala, and A Brief History of Time. If you’re a Criterion Channel subscriber who wants to follow along at home, click here.

Also, this entry is partly behind a paywall for paying subscribers and next week’s will be for paying subscribers only. We still plan to offer plenty of free content, but a paid subscription offers access to everything, including our comments section, and, of course, helps keeps The Reveal going.

Keith: In 1988, Errol Morris’s documentary The Thin Blue Line earned acclaim, stirred controversy, and even led to the release of a man imprisoned for a murder he didn’t commit. It’s not like Morris was the first documentary filmmaker to cover a crime, but rarely has a doc reversed an injustice. And the film itself looked like no doc that had been made before, including Morris’s great first features Vernon, Florida and Gates of Heaven. To illustrate the conflicting accounts of the central crime, Morris staged recreations, shooting them in a style that looked like a scene from a narrative film and pairing them with an intense Phillip Glass score. In doing so, was he playing by the documentary rules? Traditionalists argued “no” and the film was conspicuously absent from its year’s Best Documentary Feature nominees.

That didn’t put a stop to its influence, however, in ways both laudable and regrettable. Though some filmmakers, including Morris, continued to explore the possibilities of recreations, TV in the 1990s was filled with recreation-filled true crime shows that looked like the bastard children of The Thin Blue Line. Brother’s Keeper doesn’t borrow much of The Thin Blue Line’s style. It’s closer to the verité approach pioneered in the ‘60s that had become something like the norm — or at least a time-tested approach — for theatrical documentaries by the early ’90s. But it similarly attempts to get at the truth of a crime.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

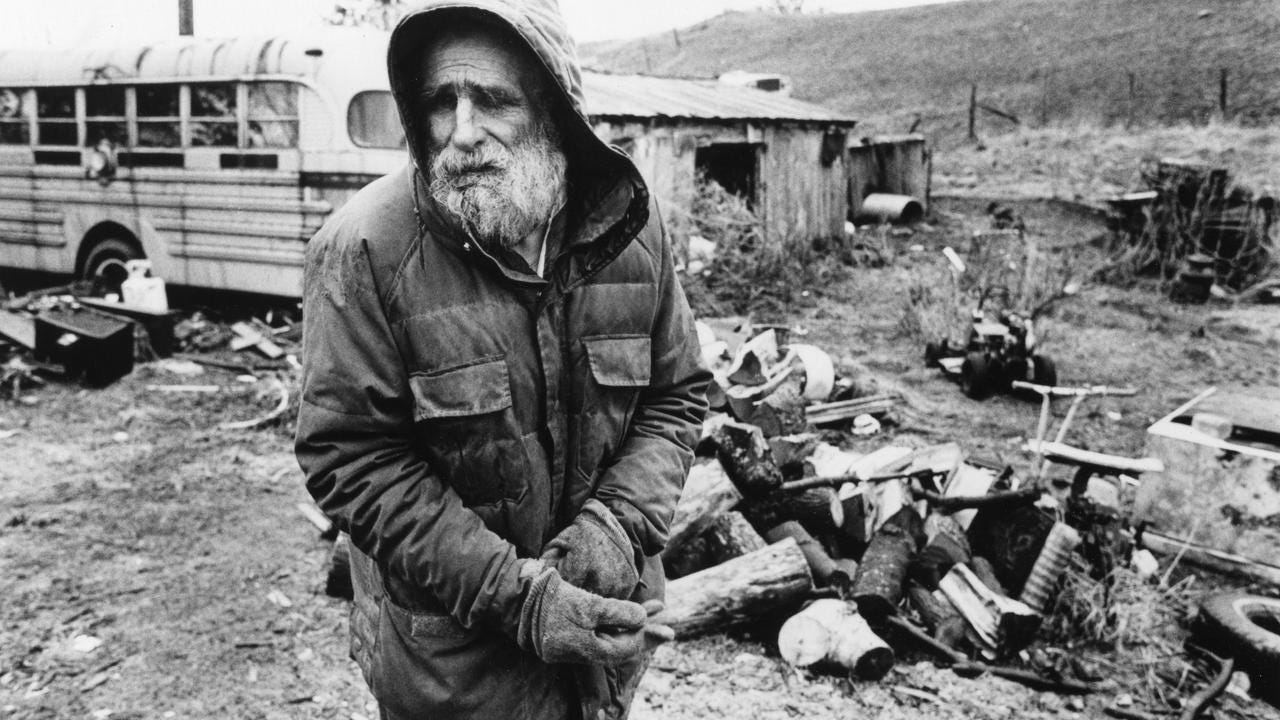

That task proves pretty elusive. The facts are these: In 1990 William Ward was found dead in the dilapidated rural New York house he shared with his three brothers. One brother, Delbert, confessed to smothering William in his sleep. William had been ill for a long time, the Wards were uneducated farm people, so a mercy killing seemed plausible. But did he actually commit murder, as he was chargd? Was the confession, as Delbert’s lawyer argues in the subsequent trial, coerced? Members of the Wards’ community, where many simply called them “the boys,” vacillate between disbelief and a lack of interest — not to Delbert but whether what he might have done should even be considered a crime. The Wards might have been simple (and pungent) eccentrics who didn’t make a distinction between euthanizing a loved one and putting an animal out of its misery, but they were their possibly murderous eccentrics, and they loved them.

Co-directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky don’t push one view or the other, though they seem to come to love Delbert and the surviving Wards, too. They might have set out to untangle a mystery, but their film ends up ensnared in the same tangles but, to the filmmakers’ credit, they seem to recognize this. Brother’s Keeper becomes less an investigation than a character study and a look at the folkways of a little-visited place. IFC packaged it with the tagline “A Heartwarming Tale of Murder.” That’s cheeky but also kind of apt. It’s a weird movie, when you step back and consider what’s expected of a documentary. It almost asks viewers to shrug at the question “Was justice done?” But it’s beguiling, too (though I’ll confess to looking away at the pig slaughter scene, even though I’m pretty sure I watched it the first time I saw this film).

Scott, what about you? Are you squeamish about on-screen pig slaughter? And did anything stand out about Brother’s Keeper 30 years later that you might not have noticed back then, or might have played differently at the time? I was fascinated by the media coverage in the film and the local reactions, and kept imagining how all this would have played in the social media era.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Reveal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.