Dialogue: Sundance '92, Pt. 1 — Anger, Yearning, Death and The New Queer Cinema

A series revisiting the landmark 1992 Sundance Film Festival kicks off with looks at 'Swoon,' 'The Hours and Times,' and 'The Living End.'

Over the next three weeks, we’re discussing films from “Sundance Class of ‘92: The Year Indie Exploded,” a series currently featured on the Criterion Channel. This week, we’re talking about the New Queer Cinema of Swoon, The Hours and Times, and The Living End. Next week, we’ll bring in documentaries like Brother’s Keeper and Incident at Oglala. And we’ll wrap it up the following week with two films by women directors, Gas Food Lodging and Poison Ivy. If you’re a Criterion Channel subscriber who wants to follow along at home, click here.

Scott: Keith, what excites me about the new Criterion Channel series on Sundance ‘92 is that the list of films on offer understands the Sundance Film Festival not as the giant commercial marketplace it would become, but as a wellspring for genuine independent work. When we think about watershed moments for Sundance, our minds naturally lead to other years that “indie exploded”: Like 1989, when Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies and videotape picked up the Audience Award before swiping the Palme D’Or at Cannes, launching not only his career, but those of the Weinsteins, Harvey and Bob, whose Miramax distribution company demonstrated the crossover potential of low-budget cinema. Or you could jump ahead to 1994, the year of Clerks and Hoop Dreams and Spanking the Monkey. Or 1995, when Ed Burns’ The Brothers McMullen won the Grand Jury Prize and a new studio boutique label, Fox Searchlight, helped usher in a boom of mini-majors that muddied the waters on what even qualified as “independent.” But that’s a discussion for another time.

To frame Sundance ‘92 as “the year indie exploded” is heartwarming, as at the time these reverberations were not really felt in the mainstream. But they were certainly felt by young cinephiles like me. As a 20-year-old in Athens, Georgia, I’d frequently pile into a car with friends and drive to Atlanta to see indie and foreign films at arthouse theaters like Loew’s Tara (now the Regal Tara) or Garden Hills, which no longer exists. One experience I can vividly recall was seeing Todd Haynes’ Poison in a sold-out screening in Atlanta, and what struck me then, beyond the particulars of Haynes’ conceptually daring and provocative work, is the level of interest that filmgoers had in a film that was so defiantly uncommercial. Poison had won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 1991, and would go on to cross the $1 million box office threshold, which may sound like a pittance now, but was an exceptional marker of success. It proved that American indies broadly, and gay cinema in particular, had an audience. If a sustainable business model could be built around an experimental and occasionally alienating triptych of stories inspired by Jean Genet stories, anything was possible.

The very next year, the New Queer Cinema of Sundance ‘92 surged on that potential. Indie legend Christine Vachon, who’d produced Poison, came to Sundance with Tom Kalin’s Swoon, a black-and-white treatment of the Leopold and Loeb story that, like Poison, did not care to ingratiate itself to the mainstream. In fact, it seeks to challenge its intended audience by revisiting a case that had so often been held up as evidence of the supposed psychotic aberrance of homosexuality. There’s a distinct note of anger and defiance that runs through the trial in the last part of Swoon—and we’ll see again, amplified, in The Living End—but getting there necessitates a low-budget rendering of Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb’s horrific crimes, which were spun out of arrogance and amorality.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

In plotting the kidnapping and murder of a 14-year-old boy, Leopold and Loeb had reputed endeavored to stage “the perfect crime” and get away with it. Kalin doesn’t have the resources (or perhaps the interest) to invest much detail in the scheme’s planning or execution. Instead, he emphasizes the heady rush of their relationship, the mingling of sex and mischief that escalated from petty vandalism to cold-blooded murder, almost on a dare. Kalin doesn’t shy away from this vile, arbitrary, utterly pointless act of destruction, and he takes a major risk in associating it with the “deviant” behavior that’s long been attached to gay characters. But the heart of the film, to my mind, is the trial itself, which is bracing in its treatment of the vicious homophobic rhetoric that prevailed at the time. The courtroom is cleared of women (and journalists) whenever the graphic details of Leopold and Loeb’s relationship are discussed, and Kalin makes the prosecutors sound as detached from reality as the men they’re hoping to execute. The crime is shocking and so is the official answer to it.

What did you think of Swoon, Keith? And what are your impressions of the New Queer Cinema at the time?

Keith: To answer your second question first, I was late to it. I caught Poison later in the ’90s and all the other films we’re covering this week are new to me, and I’m not sure why. I certainly should have caught up with these films at the time, and I’m glad to get the chance to catch up with them now. But even from the remove of, wow, thirty years, it’s not hard to see how radical these movies were. No doubt some part of Poison’s success can be attributed to it being a bit of a scandal at the time, thanks in large part to the vocal protests of the American Family Association. (Thank you, American Family Association.) There’s nothing shy or polite in it, nor any interest in courting the mainstream. The same can be said of Swoon, which is stylized in ways that can be off-putting at first and isn’t viewer friendly at all for those unfamiliar with the case of Leopold and Loeb. It also doesn’t shy away from the sexual desire that fuels their crimes (or from a fairly explicit depiction of their sexual lives). Their murder is unspeakably vile, but to them it’s part of the hazy eroticism they’ve created to surround themselves in. Swoon is a film daringly made from the inside of that haze looking out. (Or, as Richard Brody put it in a recent New Yorker capsule, it captures and lives within “ the killers’ recklessly aestheticizing mind-set.”)

It’s far from a modest, polite plea for acceptance, in other words. (Growing up in the ’80s I think the first gay character I encountered in media of any kind growing up was the fussy, kind, “confirmed bachelor” Sidney Shorr, played by Tony Randall on the sitcom Love, Sidney—and even then only realized it because I read it in an article about the show. Of course, at the time I just thought of Paul Lynde as “that funny guy with the odd voice.” at the time.) Like other films we’re covering this week, it goes for complexity even when that complexity makes the film uncomfortable. But you’re right that it ends up getting at the ugliness of the era’s homophobia — and depicting how little had really changed since the 1920s — via its courtroom scenes. And it’s worth remembering, as The Living End makes more explicitly clear, just how homophobic the times were at the end of the Bush era. (Not that Clinton, Ellen, and other developments later in the decade solved that issue.)

Like Swoon, Christopher Munch’s bite-sized debut feature The Hours and Times looks to the past, here in an attempt to understand the deep bonds and contradictions at the heart of an intense but ill-defined relationship.

Specifically it imagines what might have happened during a much-speculated-about weekend getaway taken by John Lennon and Beatles manager Brian Epstein, the former a working class musician in the first blush of superstardom, the latter a wealthy, gay scion of a Jewish family. That might sound like the set-up for tabloid-y speculation about the private life of a musical icon, but that’s not the sort of film Munch made.

Instead it’s a rich and moving depiction of the friendship between two people who need each other but can’t quite negotiate what form that need takes. For Brian (David Angus, who delivers a remarkable performance but seems mostly to have spent the years since the film working behind the camera in children’s entertainment), it’s a relationship filled with romantic yearning and unrequited sexual desire. For John (Ian Hart, who’d play Lennon a couple times more), it’s not that. Except maybe it is. He’s deeply curious about Epstein’s sexual life and encourages his attentions, at least up to a point.

In a phone conversation with his wife Cynthia we see a dynamic similar to the one between him and Brian: John encourages her until he pushes her away. It’s how he relates to others, and arch, cutting mannerism squares with the Lennon we know from interviews, even though Hart’s performance goes beyond mere impression. John’s a jerk, but you can see what makes him so attractive, including the suggestion that someday he’ll stop being a jerk and return their affection unreservedly. Brian, by contrast, isn’t just a dummy being drawn along. He feels deeply for his friend and understands his limits, and the limitations of the times. Munch ultimately makes this more about Brian than John, too, a portrait of a man at the center of ’60s glamor playing an integral part to bringing the Beatles to the world but unable to enjoy his life to its fullest for a multitude of reasons, of which his love for John is only one. I’m not entirely sure what the title means, but the handful of hours it depicts plays like a window into the times it portrays.

How about you, Scott? Had you seen this before? Its hushed, delicate tone is a pretty stark contrast to the final film we’re covering this week, isn’t it?

Scott: I had seen The Hours and Times, as well as Münch’s two subsequent films, Color of a Brisk and Leaping Day and The Sleepy Time Gal. Of the latter, my review in The A.V. Club cited his “European” sensibility, and how unusual his formalized style appeared to be in American films at the time. And I think that holds true of The Hours and Times, which isn’t a provocation like Swoon or The Living End, and perhaps fits a bit oddly within the New Queer Cinema scene as a result. This is a small piece of speculative history, not a shot across the bow of the establishment.

But oh what a lovely little movie. As you noted, Hart would play Lennon again a few years later in Backbeat, a mostly solid chronicle of the Beatles’ early days in Hamburg, Germany, with quite a bit of material on Lennon’s relationship with Stu Sutcliffe, the band’s original bassist. What’s remarkable about Hart’s casting in both films is that he doesn’t look much like Lennon at all, but his voice and his general aura are so persuasive that it doesn’t matter. In The Hours and Times, his Lennon’s poised on the edge of stardom and already has that rock-star confidence and enigmatic behavior.

The centerpiece is the bath scene, where John is in the tub and asks Brian to scrub his back. One thing leads to another, as they say, and the two end up in the tub together, making an attempt at foreplay. For John, a wannabe libertine, this is an experiment: Where does he land on the Kinsey scale, anyway? Can he accommodate his friend and manager sexually, even as a one-time tryst? For Brian, of course, the moment is a culmination of a desire that he can barely suppress when he’s spending time with John. Only John discovers that he doesn’t want to go through with it and he exits the tub without a word, leaving a perplexed and disappointed Brian to sit with a passion that’s now definitively unrequited.

John isn’t the sort to articulate his feelings directly, and he’s a little immature, still a young man tomcatting his way around, happy to walk through the doors his nascent stardom is opening for him. But make no mistake: This was a friendly gesture. He wanted to see if perhaps he could do this for Brian. The Hours and Times is a sweet movie, fundamentally, and as pristine and perfectly judged as a great short story—or one of Epstein’s outfits. Though he does include a couple of key supporting characters who drift in and out of the film—a scene with Lennon and a stewardess is particularly sharp—Münch is essentially staging a two-hander over a limited time on a limited budget. And the black-and-white, like the photography in Swoon, covers up as much as it evokes. But the film is a great example of less-is-more filmmaking: There’s much to savor in the details of costume and decor, and the attention to the performances. Debut films are rarely so precise.

Which certainly cannot be said of Gregg Araki’s extremely raw, unfussed-over, seat-of-your-pants road movie, The Living End. Back in 1992, if you had to guess which of these three filmmakers would have the brightest future—Tom Kalin, Christopher Münch, or Araki—you’d have to put Araki a distant third on that list. (And I don’t mean to take anything away from Kalin or especially Münch, who isn’t prolific, but continues to do interesting independent work to this day.) I have strong memories of helping to program The Living End for the Tate Theatre on the University of Georgia campus when I was an undergraduate and being knocked back by its no-holds-barred recklessness, which felt then and now like a middle finger to a deadly, politically conservative era in American politics.

Araki would stay in this vein for the next film, 1993’s Totally Fucked Up, the first in his “Teenage Apocalpyse” trilogy, followed by 1995’s The Doom Generation and 1997’s Nowhere. But starting with Nowhere, he would gradually evolve into a director of often campy, candy-colored, omnisexual romps like 1999’s Splendor and 2010’s Kaboom, and showed some range elsewhere with the devastating 2004 drama Mysterious Skin and the delightful 2007 stoner comedy Smiley Face. You don’t have to squint that hard the seeds of Araki’s future planted in The Living End, but he obviously had some growing to do. The road movie format is forgiving in that respect. It allows filmmakers to lurch around, make mistakes, show flashes of inspiration, and generally learn on the fly.

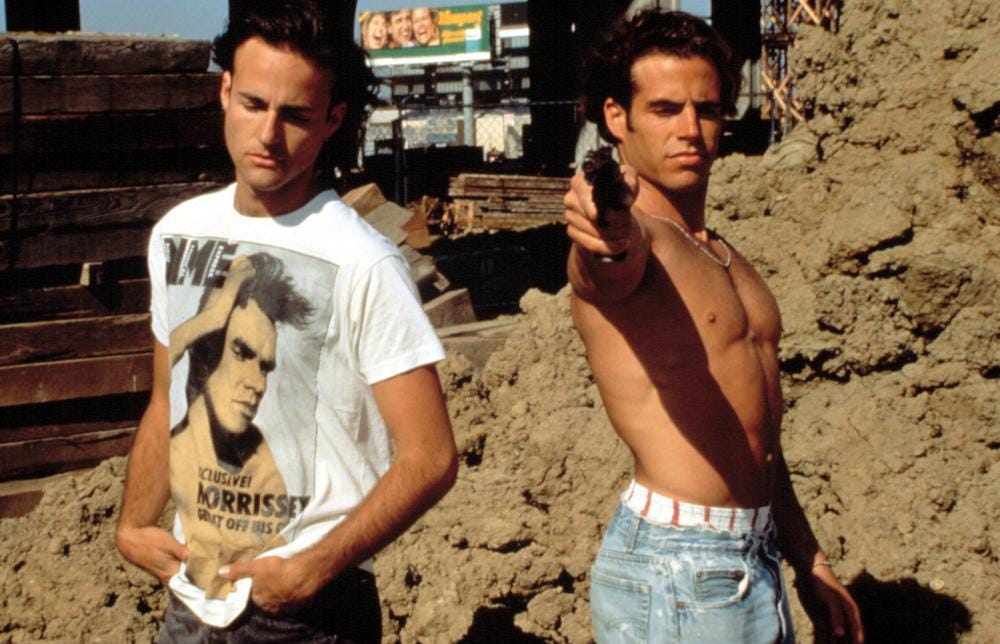

Comic disaffection and angry nihilism—along with amorousness, of course—are the forces that propel The Living End forward, and surely there’s some of Araki in the character of Jon, an HIV-positive freelance film critic who picks up a hot drifter, Luke (Craig Gilmore), also HIV-positive, and hits the road to nowhere after Luke kills a homophobic police office. Araki’s interest in music and popular culture are a big part of his work, it seems certain that when critics likened The Living End to 1991’s Thelma and Louise, he deliberately courted the comparison. The sad truth of this film is that these characters are headed off a cliff and they know it, just like others infected with a deadly disease that the country’s leaders had met with indifference at best. Hence the dedication at the end, to “the hundreds of thousands who’ve died and the hundreds of thousands more who will die because of a big white house full of republican fuckheads.”

I believe this was your first Araki, right Keith? How did it play for you 30 years later? I think it’s very much a movie of its time, in a good way.

Keith: Yes, first time watching this film. First time watching an Araki, and I’m not sure why. (He’s made many films on my “I need to get to that someday” list, so maybe it’s time to start catching up.) I liked this one a lot. It’s unwieldy and sometimes obviously a first film made on an extremely limited budget but I think that’s also part of its power. And it also has a lot more style than many first-time, limited-budget films, like that phone booth split screen sequence, which cleverly achieves an “optical” effect by simply splitting the composition in half with a divider between them. Very clever. Araki’s not shy about pointing to his influences. Jon’s apartment features posters celebrating the work of Godard and Warhol, for starters and the Mary Woronov cameo feels like one generation of cult filmmaking giving a nod of approval to the next. And as for it being a movie of its time in a good way, absolutely. It’s a time capsule, from its outrage at the politics of the George H.W. Bush administration to Jon’s Wax Trax-heavy CD collection and love of the Smiths, the lattermost a remnant of a time before Morrissey’s name, sigh, became synonymous with right-wing extremism. (I was there. We didn’t see that coming, though Cornershop started sounding the alarm a few months later.)

It’s Araki’s daring that really sets it apart, however. You quote the angry closing statement, but the opening titles also double as a statement of intent, announcing it as “An Irresponsible Movie by Greg Araki.” In one sense, that’s entirely true. It’s filled with violence, anti-authoritarian gestures, and characters who decide to treat their diagnosis as an excuse to live outside the law (shades of Swoon but with much less sociopathy and much more understandable rage). But it also holds to an outraged sense of higher responsibility, as it depicts the madness of trying to live a normal life when a disease is ravaging your community, and is certain to cut your own life short, all while those in power, and much of the rest of the world, pretend it wasn’t happening. It’s also, for all its determined tastelessness and shocking moments, an extremely moving film, ending on an image of characters living in the shadow of death—but still living. It’s forceful and impolite and, years later, still exciting.

Next week: The documentaries of Sundance ‘92, with a focus on Incident at Oglala and Brother’s Keeper (and maybe more). Also, this will be the last entry in this series available in full to non-paying subscribers. But accessing future entries isn’t the only reason to subscribe. Your support helps keep The Reveal going, opens up commenting privileges, and guarantees nothing will be behind a paywall for you in the future.

I was at a screening a few years ago of Christopher Munich’s LETTERS FROM THE BIG MAN, and before the movie David Ansen disclosed that the Sundance jury almost awarded top prize to THE HOURS AND THE TIMES, but got talked out of it, I think because of the short length.