Catching Up with the Critics (Part II)

Another round of critical favorites brings more best-of-the-year candidates. And a lot of Dolly de Leon.

In the first part of my annual movie catch-up feature, published last week, I opted to switch the format from the best films I hadn’t seen according to Metacritic, as I’d done in the past, to the best films I hadn’t seen according to my trusted friends and colleagues in the critical community. And, much to my non-surprise, I quickly discovered that I’d be seeing a better crop of films than in previous years, including two films, India Donaldson’s Good One (recommended by our own Keith Phipps) and Pascal Plante’s Red Rooms (recommended by Mike D’Angelo), that stand to make my annual Top 15 list at the end of 2024. In this week’s edition, we have at least a couple more list-worthy additions, along with a few other gems, courtesy of Justin Chang, Manohla Dargis, Jason Bailey, Alissa Wilkinson, and Bilge Ebiri. Let’s get to it!

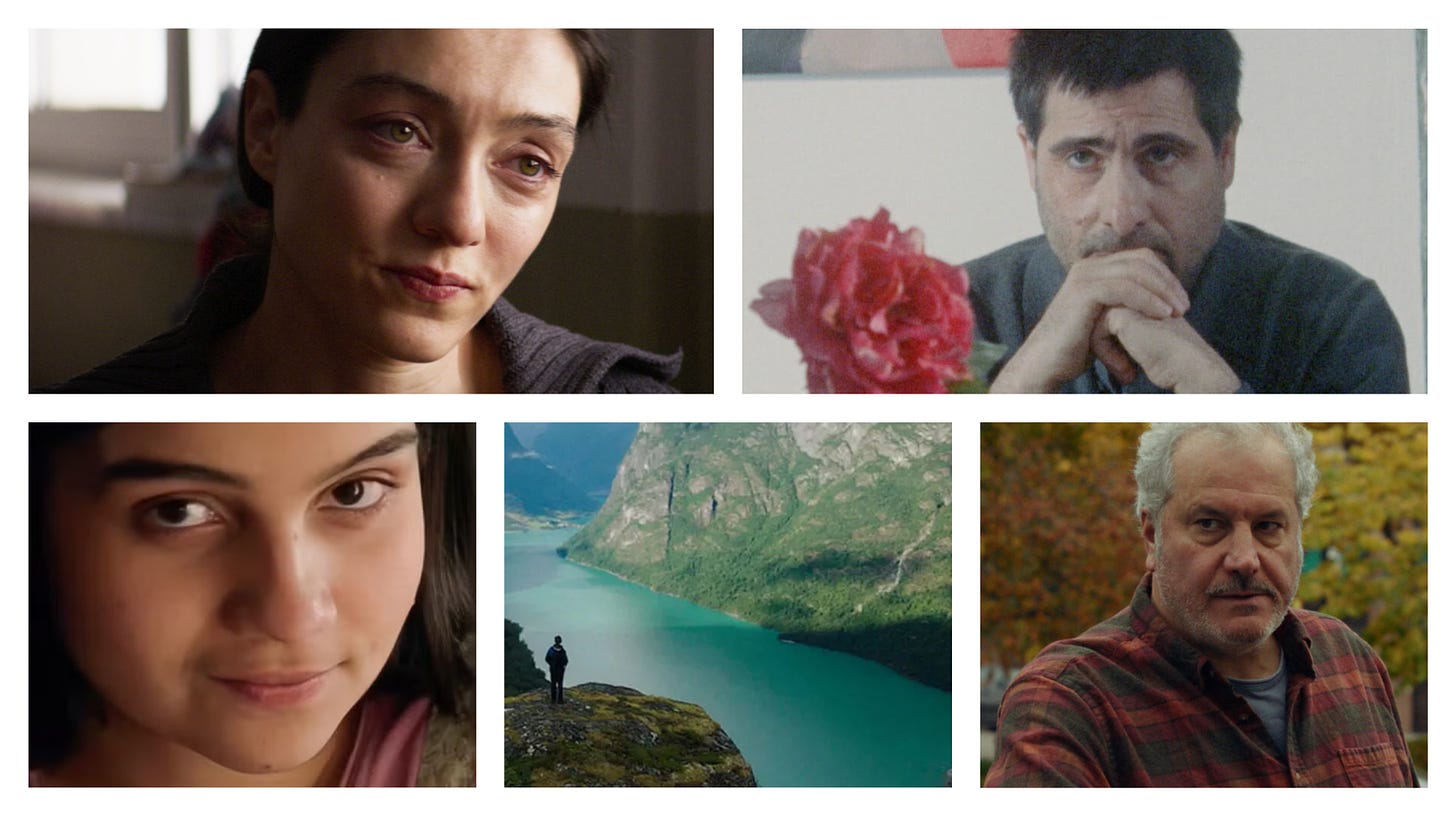

About Dry Grasses (dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan)

The critic: Justin Chang, The New Yorker

How to watch: On Criterion Channel; also available for rental. On Criterion DVD/BD 10/22.

List-worthy?: A lock.

Premise: Working his fourth year as a middle-school art teacher in a snowy Anatolian backwater, Samet (Deniz Celiloğlu) hopes to transfer to the more cosmopolitan Istanbul after completing his obligatory time there, but his plans are clouded by an accusation of improper conduct by a favorite student. Meanwhile, Samet takes a growing romantic interest in Nuray (Merve Dizdar), a teacher at another village whose idealism and activism stands in stark contrast to his stubborn cynicism.

Justin’s thoughts: “About Dry Grasses may be unhurried, with languid steppe-by-steppe pacing and long, luxuriant, exquisitely sculpted conversations, but it is also nimble, alert, and alive in ways that seem to have taken Ceylan himself by surprise.”

My thoughts: Of the films the great Turkish director Ceylan has directed, his thorny 2006 relationship picture Climates (affectionately referenced by Josh Brolin in the Coen brothers short “World Cinema”) and his sprawling 2011 procedural Once Upon a Time in Anatolia remain my favorites, so perhaps it’s no surprise that I’d be game for a mesmerizing three-plus-hour drama that combines the insight and emotional friction of one film with the regional specificity of the other. It takes time for About Dry Grasses to get its hooks in you, because the problems that the difficult-to-like Samet has with a teacher’s pet at his school are not as immediately captivating as his relationship with Nuray, whose passion and humanity holds his sour, rudderless existence in sharp relief. But these two pieces of About Dry Grasses come together profoundly in the end, when we have the fullest possible glimpse into Samet’s state of mind. (If you’re spending the whole movie asking, “Where are the dry grasses I was promised?!”, hang in there for a big payoff.) Though we’re told there are two seasons in Anatolia, winter and summer, Ceylan sticks mostly with the relentless snow and cold that heighten Samet’s sense of isolation, like Fargo without the firewood and fricassee. Yet there’s plenty of fire burning in Merve Dizdar’s astounding, Cannes-winning performance as Nuray, who lost her leg to a suicide bomber while protesting injustice, but has clearly not lost any of her fierce compassion. A long scene where the two talk over dinner at Nuray’s place is a master class of performance and staging, with Dizdar’s Nuray emerging like a flame from low light to counter her guest’s studied apathy. Hers is a face I won’t soon forget.

Between the Temples (dir. Nathan Silver)

The critic: Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

How to watch: Rentable on major services.

List-worthy?: Yes.

Premise: Roughly a year after his wife’s death, Ben Gottlieb (Jason Schwartzman) has moved home with his two mothers (Caroline Aaron and Dolly de Leon) and lost his singing voice, which affects his work as a cantor at his synagogue. His crisis of faith takes a turn when he reunites with his former elementary-school singing teacher, Carla Kessler O’Connor (Carol Kane), who shows an interest in having him instruct her for a late bar mitzvah.

Mahohla’s thoughts: “The movie is consistently funny, but its humor tends to be fairly gentle because it’s rooted in human behavior rather than in condescending, judgmental ideas about such behavior.”

My thoughts: Dargis likened one scene at a restaurant to Elaine May’s great black comedy The Heartbreak Kid, and May’s scabrous, uncomfortable, messily human sensibility seems like the right point of comparison for the film overall, too. Though director Nathan Silver and his co-writer, C. Mason Wells, put Ben in many hilariously awkward spots, they have an underlying respect for the grief and humility that make him vulnerable and for his unexpected (and again, funny) way of asserting his will when he discovers it. Schwartzman has never been better and Carol Kane, a veteran ringer in comedies, proves an equal partner in her longing for a spiritual and emotional piece that’s missing from her life. Their mutual assistance—him in instructing her for an unorthodox coming-of-age, her in helping him find his voice in multiple senses of the term—leads to a relationship that smacks of another ‘70s classic, Harold and Maude, and its rough-hewn qualities are reinforced by Sean Price Williams’ grainy 16mm photography and the jagged shards in the editing. A climactic Shabbat meal brings the entire stellar ensemble together for a scene of insane, seriocomic, Cassavetes-esque chaos, but it’s emotionally true all the same.

Girls Will Be Girls (dir. Shuchi Talati)

The critic: Jason Bailey, Crooked Marquee

How to watch: In theaters

List-worthy?: Honorable mention.

Premise: At a conservative boarding school at the foothills of the Himalayas in the 1990s, Mira (Preeti Panigrahi) becomes the first girl ever selected as head prefect, a testament to her high grades and moral discipline. But her orderly world starts to unravel when Sri (Kesav Bin Kiron), a rebellious newcomer, catches her attention and sparks a sexual awakening that threatens her standing at home and in school.

Jason’s thoughts: “If the narrative is familiar, this is one of those ‘not what it’s about, but how it’s about it’ situations, writ large. Girls is a marvelously lived-in movie; Talati’s writing and direction is so confident that within minutes, you feel as though you already know [Mira and Sri], and the world they inhabit.”

My thoughts: Immediately engaging as a story of star-crossed first love, Girls Will Be Girls wastes no time establishing both the stakes of Mira’s new stature at this extremely traditional school and her thunderstruck attraction to Sri, whose charisma and worldliness sets her heart (and libido) aflutter. Yet Mira’s mother (Kani Kasruti) is just as important an obstacle here, because the relationship happens both through and around her, and her motives are much cloudier than they appear to be. Though Talati doesn’t take enough advantage of her Himalayan setting—the premise alone immediately suggests Black Narcissus, but the film doesn’t have that level of visual heat—she’s refreshingly frank about how Mira’s desire manifests itself, from a fervent masturbation session to her scholarly online research into sexual mechanics. But Talati is keenest of all in understanding how gender dynamics and its related hypocrisies can break a girl’s heart just as surely as betrayal.

Songs of Earth (dir. Margreth Olin)

The critic: Alissa Wilkinson, The New York Times

How to watch: Strand Releasing’s streaming platform. Rentable on major services.

List-worthy?: No.

Premise: Mixing the natural with the personal, Olin’s documentary pays tribute to her aging parents, Jorgen and Magnhild, who have been married for 55 years and still live among the breathtaking mountains surrounding the Oldedalen valley in the western part of Norway.

Alissa’s thoughts: “It’s rare to see a film that feels not just poetic in nature, but like actual poetry. The rhythm and cadence, the imagery and metaphor, even the sense of movement and time that often accompany a great poem don’t translate easily to the screen. Filmmakers need a light touch and trust in the viewer to lean in and let their work wash over them, rather than trying to decode everything. Margreth Olin somehow pulled it off — and in a documentary, no less.”

My thoughts: There’s enough poetry here as Alissa describes it—in the jaw-dropping splendor of nature at its most majestic, along with a lovely score by Rebekka Karijord—that makes you wish Olin had committed more fully to the associative abstractions of the film’s strongest moments, like when the pulsing groans of a cracking glacier merge into close-ups of her father’s own frail body as his mighty heart thumps. Though Olin divides the film up neatly into four seasons, there are times when the aerial camera movements over this Norwegian idyll made me feel like I was on the sales floor of an appliance store, gawking at the latest advancement in HD resolution. That’s an unreasonably harsh view of Olin’s filmmaking, which is significantly more artful and intentional than that, but Songs of Earth falls back on convention a bit. Nevertheless, the love Olin has for her parents—and they for each other—is so powerful to witness, and their perspective on the lives they’ve had together and its inevitable end feed into the film’s thoughtful musings on ancestry and legacy.

Ghostlight (dir. Kelly O’Sullivan and Alex Thompson)

The critic: Bilge Ebiri, Vulture

How to watch: Rentable on major services

List-worthy?: No.

Premise: Still reeling from his son’s death, Dan (Keith Kupferer), a construction worker, gets coaxed into performing in a community theater production of Romeo and Juliet. Meanwhile, his daughter (Katherine Kupferer) gets in trouble at school and he and his wife (Tara Mallen) are pursuing a wrongful death lawsuit against the person they hold responsible for their loss.

Bilge’s thoughts: “In the end, it becomes a film about the world-changing power of artistic communion, about how creativity, compassion, and forgiveness — of oneself and others — are all pit stops on the same human journey.”

My thoughts: There’s no question Ghostlight packs an emotional wallop if you’re open to what it’s attempting to do, which is a tribute to the sincere commitment of the performances and its earnest yet hard-won and hopeful vision of creative expression as a means to emotional well-being. But the premise is a conceptual Mount Everest that I’m afraid I was unable to scale, especially given the absurd contrivances involved in bringing it together. I never believed that a theater member (star-of-the-moment Dolly de Leon) would bring Dan in off the streets because she sensed that he “needed” the experience, and the associations between Romeo and Juliet and the particulars of his son’s death are too close for the coincidence to be tolerable for me. Even making Dan a construction worker, the archetype of a hard-headed hard-hat, is a little on the nose for a film that’s already emotionally direct by nature. Yet I’m not inclined to pull this butterfly apart by the wings, because Ghostlight reflects the spirit of community theater so purely, believing with conviction that putting on a show, however corny or haphazard, can be as meaningful a communal experience to the cast and the audience as any professional operation. I still welled up despite myself.

Anyone else see ABOUT DRY GRASSES? Dizdar deserves an Oscar and I’ll hold the ceremony in the alley behind my place if necessary.

Ditto on Ghostlight; once you get over the familarity of the plot points themselves, the actually staging of Romeo and Juliet is handled very patiently and got my hard heart to shed several tears