All the Oddballs Come Out At Night: On 'After Hours'

Faced with a series of career setbacks, Martin Scorsese scaled down and broke out with his black comedy about a surreal night on the town.

“You wouldn’t believe what I’ve been through tonight.”

“I’m an ice cream vendor. Mister Softee.”

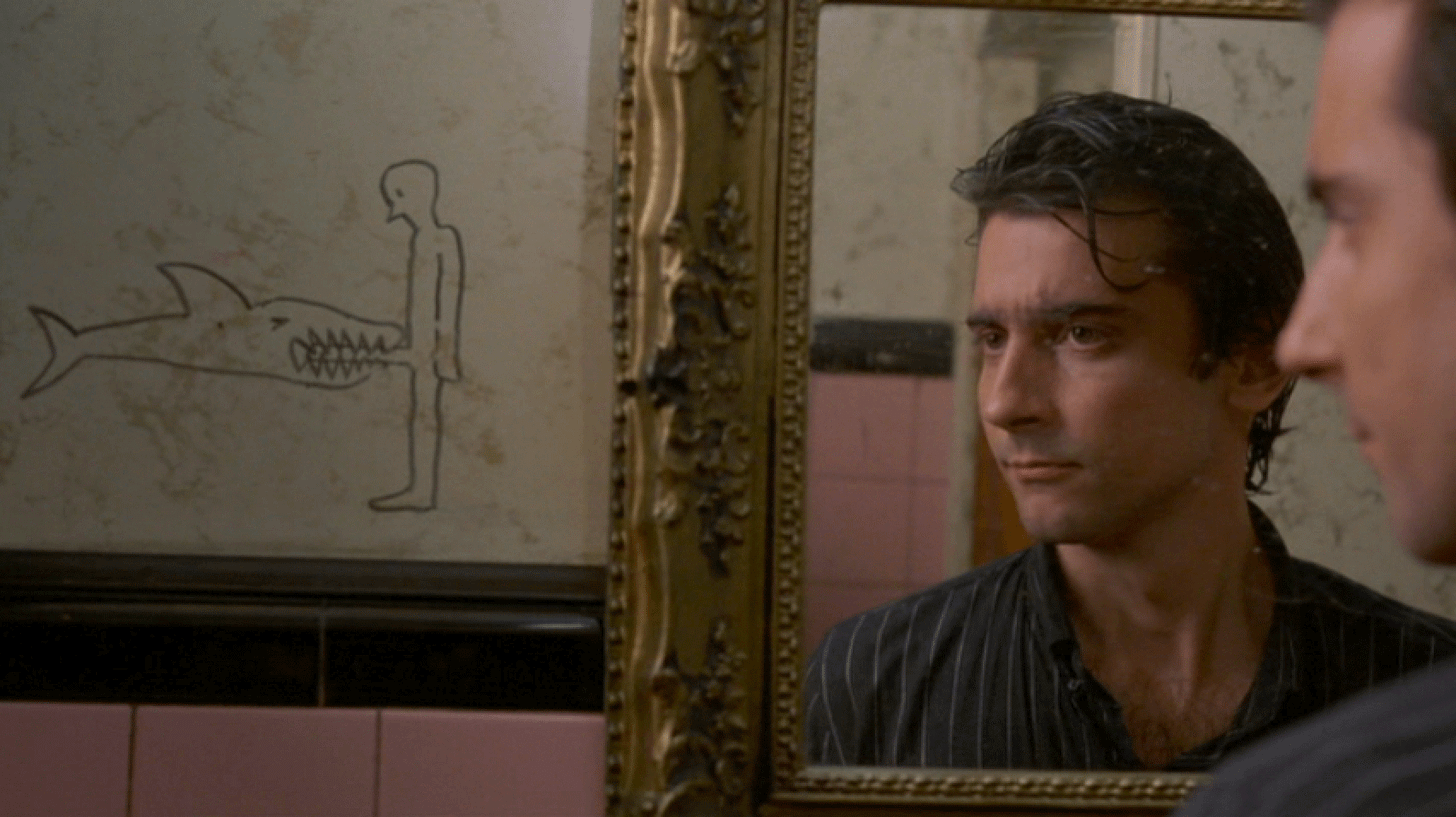

These are not two random lines of dialogue in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours. They come one after the other, a plea for a sympathetic ear followed by a bizarre non-sequitur. It has been that kind of night for Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), who struck out to SoHo for a romantic adventure in the hippest of downtown neighborhoods—read: he wanted to get laid—and has now slipped into a endless miasma of bad luck, misunderstandings, and an almost conspiratorial force preventing him from getting back home, as if the streets of Manhattan were being redrawn by M.C. Escher. As much as New York itself has a knack for upending people’s plans, it’s the universe that appears to be speaking to Paul. Or maybe God Himself. When he’s deposited in front of his dreary workplace at dawn, Scorsese makes it look as if the Gates of Heaven have finally cracked open and shown him a little mercy.

Yet the exchange above speaks to two themes that run through After Hours: That Paul has trouble understanding and communicating with women, and that Paul isn’t the only person in New York with a problem, even if the film makes it seem like the city has targeted him specifically. In this scene, Paul has begged his way into a stranger’s apartment, desperate to escape the vigilante mob that’s been chasing him and to use her phone so he can make his way home. The stranger, played by Catherine O’Hara, is acquiescent, but she must be acknowledged at this moment, too. The least Paul can do, from her perspective, is to know that she’s an ice cream vendor with her own Mister Softee truck and perhaps to learn she’s an adult with sexual interests, too. He’s not the only night owl in SoHo looking for a little action.

For Scorsese, After Hours was an opportunity to go small and clear the decks after a series of studio features—1977’s New York, New York, 1980’s Raging Bull and 1982’s The King of Comedy—that didn’t find much financial success, or, save for Raging Bull, the critical support he was used to getting. He was also reeling from the disappointment of his dream project, The Last Temptation of Christ, falling apart at the last minute. Though The King of Comedy would age into a widely acknowledged masterpiece about celebrity culture, Roger Ebert called it “one of the most arid, painful, wounded movies” he’d ever seen, which he should have intended as more of a compliment than his three-star review suggested. Whatever the case, it was an atypical Scorsese picture, with an inactive camera that seemed intended to reflect the boxed-in artlessness of television—the only real “liberation” in the film are the delusional fantasies of its antihero. To put it in comedy terms, it’s Scorsese’s idea of stylistic deadpan.

After Hours springs forward like a jack in the box, as if Scorsese had to release all the energy he’d deliberately repressed for The King of Comedy. With Mozart’s “Symphony in D major ‘No. 45’” zipping along at a mad tempo, the credits flutter by at maximum speed before the opening shot, which pirouettes through the maze of cubicles where Paul works in word processing. He’s trying to teach a trainee (a pre-fame Bronson Pinchot) his data entry protocol, but the trainee is blathering on about it being a “temporary” job, and Paul’s mind drifts off. He doesn’t need any reminders that his work is mindless drudgery, and the film is about his bold, doomed attempt to keep that drudgery from swallowing up his free time, too. As Paul will plead later, “You know, I just wanted to leave my apartment and maybe meet a nice girl, and now I’ve gotta die for it?!”

Though Paul never has control over where the evening takes him, this is a Scorsese movie, which means he’s paying for his sins. The active sin here is lust, which propels him from the diner where he meets Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), a gorgeous young woman who spots him reading Tropic of Cancer, and into a car to SoHo, ostensibly to buy a plaster-of-Paris bagel-and-cream-cheese paper weight from her sculptress roommate Kiki (Linda Fiorentino). But lust isn’t really the sin for which the universe is punishing Paul. The real sin is his failure to understand and communicate with women, which is what binds Paul to Scorsese’s protagonists in Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and so many other films. Those men act out violently on the world. They affect it, toxically. Part of what makes After Hours a comedy is that Paul just gets pummeled, like one of the Three Stooges.

Working from a screenplay by Joseph Minion—submitted as a Columbia University thesis (Minion got an “A”), though the script’s origins were later questioned—Scorsese made what he called a noir parody, which seems as good a way as any to describe the film’s distinct texture. His New York here is a little emptier than “the city that never sleeps” and even shorter of the city as Travis Bickle describes it, “where all the animals come out at night.” It is a lonely, shadowy place, populated by freaks and eccentrics or people who simply work late or are too troubled to get some sleep. It’s impossible to imagine Kiki, a punk-artist with a taste for casual S&M, existing at all during the daytime, which terrifies Paul, who has stepped boldly and perhaps foolishly into her world. But the overall tone of After Hours, beyond its manic conspiracy of surreal comic events, is one of mystery, underlined by a brilliant Howard Shore score that ticks like a clock, but feels as sinewy as a spider’s web.

Minion’s script is bound tightly by cosmic coincidence: When a crazy cab ride separates Paul from his lone $20 bill, the same driver turns up (and leaves) at his time of need. When Paul’s troubling date with Marcy ends with a tragic discovery, he winds up finding shelter at a bar owned by her current boyfriend Tom (John Heard). After Paul chases down two burglars (Cheech and Chong) he suspects have run off with Kiki’s papier-mâché version of “The Shriek” (“The Scream,” she corrects him), they later collect him when another woman (Verna Bloom) plasters him in a similar mold. It’s a Rube Goldberg machine designed just for him—and, as viewers, we’re riding shotgun on this nightmare.

And yet, After Hours is about Paul’s blind spots, too—and, perhaps, our own. Part of what makes that exchange between Paul and Gail, the driver of that Mister Softee truck, so funny is Gail isn’t listening to Paul. (And she goes on to prank him by shouting out random numbers to make him forget the numbers he just got from the operator.) But Paul isn’t listening to Gail, either. And he doesn’t understand what Marcy’s going through. And he barely humors Julie (Teri Garr), a bar waitress with a beehive hairdo who takes him out of the rain to her apartment. The hidden irony of After Hours is that most of the characters Paul meets are having a lousier night than he is: Marcy swallows a bottle full of pills and takes her own life, Tom blames himself for Marcy’s death when he hears about it, Julie quits her job at the bar while complaining about an even worse-sounding job at a Xerox shop, and even June (Bloom), the woman who treats him with motherly mercy in the end, sways to Peggy Lee’s “Is That All There Is?” as if she’s the subject.

After Hours plays hilariously on Paul’s exasperation over a night that seems to never end, with Dunne (who co-produced) ideally cast as a white-collar drone who’s alternately ineffectual and snippy in the face of it. And the film, in addition to revitalizing a director who needed to give his own career a shot in the arm, has a fascinating relationship with Scorsese’s other men, who may often be criminals and roughnecks, but align with Paul in their turbulent feelings about women. But for the other characters in After Hours, the night isn’t over at all. Paul has been delivered to a comfortable place—he seems overjoyed to be greeted by the word processor he couldn’t bear to regard the day before—and he can be grateful that he was only a visitor to this cursed nocturnal purgatory. The people he encountered will still be there after he’s gone.

After Hours was released earlier this month on a Criterion Blu-ray.

I've watched this a number of times - maybe my fav Scorcese and prob the closest he comes to feeling 'modern' in a way a lot of his other movies can't (because they more directly informed the bigger shape of mainstream cinema).

I've never really thought about how it's not just our (sort of?) protagonist who isn't listening to anyone - really, just about everyone isn't listening to ANYone in this, which causes so much of the trouble. That right there, that's an insight and now I guess I gotta watch it AGAIN.

Thanks for the spotlight on After Hours. I saw this on the big screen in 1985, as a teenager. It was my first Scorsese, and it’s still one of my favorite films ever. It’s also a film that I feel helped prepared me in a strange way for moving to New York City ten years later. I rewatched it again very recently. The clockwork image on the poster is very apt, given the way the story unfolds.

The cast is so good in this, right down to the surreal inclusion of Cheech and Chong. Always great to see John Heard show up. A terrific double feature with this might be the cheerfully dark noir The Last Seduction with, again, Linda Fiorentino.