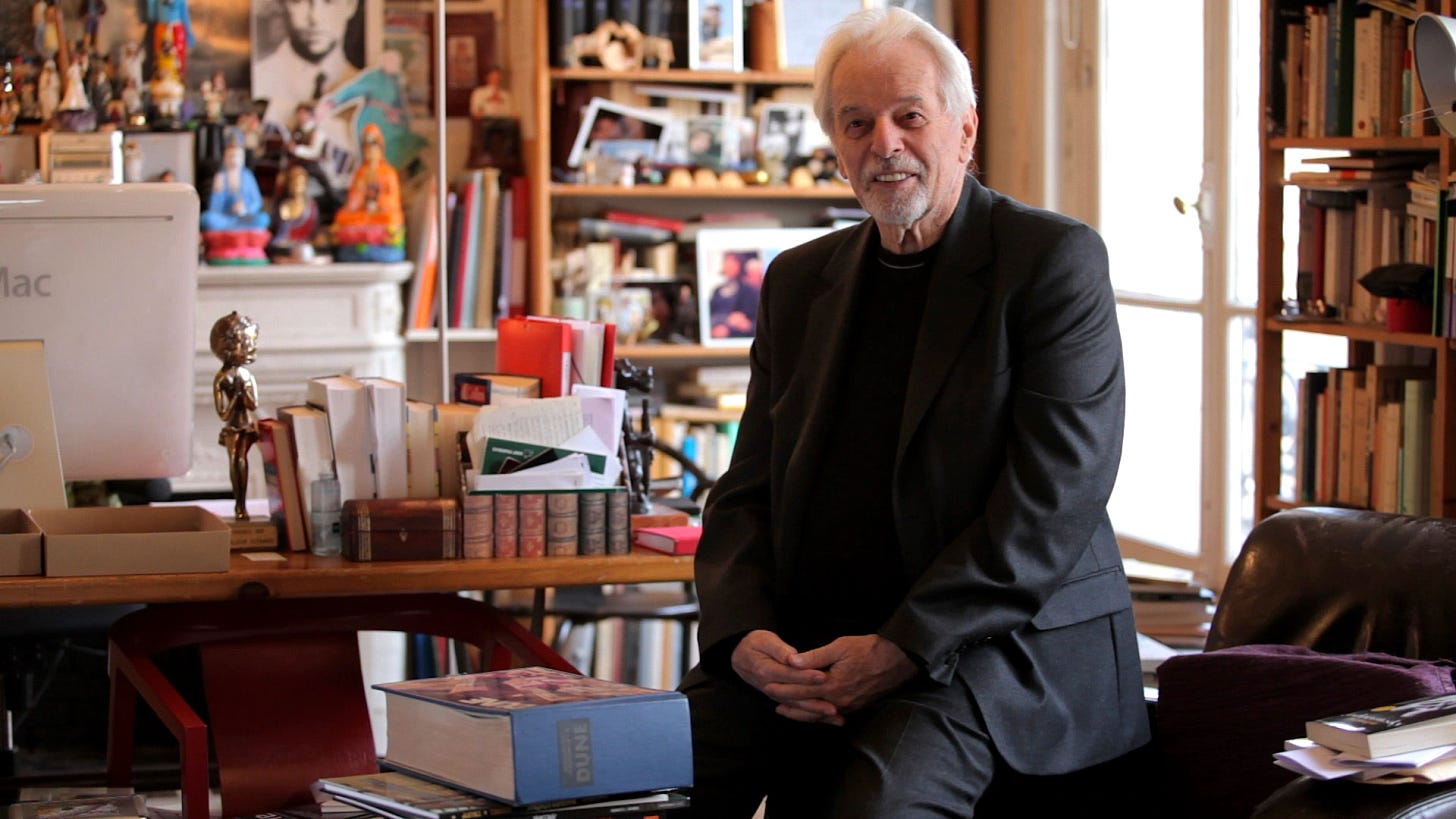

A Conversation with John Hodgman about 'Dune,' Pt. 2

In which the author and humorist gets the 'Dune' of his dreams, but wonders if the era that made it "filmable" is also an era in which it's unnecessary.

In the first part of my conversation with John Hodgman, published yesterday, he talked about his first boyhood encounters with Dune the book, David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation, the rare girl who tried to strike up a conversation with his teenage self, and the surprising airplane encounter where Peter Berg pitched Hodgman his take on Herbert’s novel. Today, the discussion shifts to Denis Villeneuve’s Dune, an adaptation that gains in cohesiveness and magnificent imagery what it loses in the expository splendors of Lynch’s “floating penis in a tank.” But Hodgman also shares some misgivings and thinks through the complexity of how this chosen one/white savior story plays in an era when it’s finally “filmable” but perhaps unnecessary. More below…

[Note: Yesterday, it was announced that Villeneuve’s Dune would get a second part. We have kept the uncertainty in the interview, however, because then there would be no mention of Ralph Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings and your lives would be poorer for it.]

Let’s shift to Denis Villeneuve’s Dune. You talk about approaches to Dune, to making it coherent to people who have not encountered the book. How did you feel the new movie pulled it off?

Let me say this. I was wrong. This is hard for me to admit. Turns out, I was wrong. Dune, at least in 2019, 2020, 2021, in this era, is absolutely filmable. And it’s good. It’s really good.

What I'll say first of all is that I do not know if it will pass the test of being narratively cohesive to someone who hasn’t been thinking about the world of Dune for their entire adult lives. I am going to see it again with our son who is 16. He’s very into seeing it. I will trust his reaction as to whether or not he could understand what was going on. But on the other hand, I will also know whether it even matters because the problem with David Lynch’s Dune was the story. That is to say, all of the work that went into explaining to you what was happening—the voiceovers, the inner monologues becoming voiceovers, the glossary, the long conversation between the Emperor and the floating penis in a tank—all of that is just elided in this version.

Villenueve’s Dune does not care if you follow the story. And if you don’t follow the story, it doesn't matter because it’s going to reward you with visually stunning, perfect images, one after the other, after the other, after the other, after the other. This is a two-and-a-half-hour long movie and I was like, “I’ll take this all day. Give me another two and a half hours. I’m ready to go. I just want to watch this. I just want to see this.” I’ll say it got understandably a little draggy in the last third or quarter, had a couple of false endings, and didn’t know when it was going to wrap up. I was annoyed that it had the false endings because I knew that it was only the first part. As I sensed these false endings approaching, I was dealing with frustration because I just wanted it to keep going.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

They have to make the second one though, right?

No, they don’t. They don’t and my guess is they won’t. How much money has it made?

It’s done well overseas, apparently. I’m hearing that chances are quite good. Because it makes me itch the idea of just leaving it where it is and then not seeing…

Yeah. No one wants a Ralph Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings situation.

Bakshi's Lord of the Rings is far from perfect.

I agree with that. A similar attempt to translate to film an unfilmable, beloved book. In his case, with very tentative studio support that got pulled immediately upon the first screening, I think. They were just like, “No, let’s fart this out there and get on with our lives.”

Bakshi was the guy who made the compromise that Jodorowsky wouldn’t, right? Hollywood wanted him to make a 90-minute movie. Jodorowsky’s like, “Why would I do that when I can make a 20-hour movie?” And he has the nerve to be like, “They turned me down for some reason!” When the Hollywood executives are like, “Hey, you know what? This is fun talking to you, but I have to live in reality. You don’t for some reason.”

That's the thing about the documentary [Jodorowsky’s Dune]. They found a group of talking heads who all had the opinion that this was just...

That this was a crime. It was a crime that this movie wasn’t made.

In the mid-70’s! When the inmates were running the asylum in Hollywood!

Of all the times that it could be made.

This is it.

Someone [in the film] said something like, “Hollywood just wasn’t ready for a visually stunning, non-narrative movie about ideas.” And I’m like, “2001 happened. What are you doing? What are you saying?” And let me just say, I love [Jodorowsky]. I love him. I’m glad he exists in the world. It is absolutely true that what he created in Dune, like the Bene Gesserit Missionaria Protectiva, seeded ideas and mythologies into creative people’s minds that have changed our cinematic culture at the very least, forever. It’s absolutely true. I absolutely believe it, right?

But my favorite part is when he goes, “Ugh, they’re all ruled by the same thing. This devil, this shit in our pocket, money,” and he pulls out like a thousand euros. He’s got a stack of twenty hundred Euro notes and he's like, “This garbage that I happen to have in my pocket.” I’m like, “Yeah. Wow. Okay. I love cognitive dissonance. You’re a very wealthy genius and you should be paid all the money in the world and I love it.”

I’d love to see that movie, though. It would’ve been an experience, right?

Yeah. It would’ve been a very wildly talked about and perhaps controversial art film that they would screen once a decade, perhaps at the Brooklyn Academy of Music or whatever. I ultimately respect, and I think that it's sincere, Jodorowsky's realization and attitude about it, which is, “This is what it was meant to be, is this book. This is what it was meant to be.” When life offers us an opportunity, you say, "Yes." When it denies you an opportunity, you say, “Yes.” It’s such a healthy worldview and it has bequeathed to us so many... As I say, it really gave us so many movies that are meaningful to guys like us with beards and glasses.

It’s not just that the book went around and people stole from it. There was a little bit of that accusation [in Jodorowsky's Dune]. But if they had made Dune, Dan O’Bannon wouldn’t have gone broke, and he wouldn’t have been staying at Ronald Shusett’s house, writing the first screenplay for Alien, and he wouldn’t have known H.R. Giger to bring him in. When you say, “Oh, it's a shame this movie wasn't made,” I mean, as the documentary rightly points out, the movie has been made, just in multiple different forms.

That’s fair, for sure. Plus his son has all of these skills that can carry forward.

His son has one of the most incredible names. I wrote it down. “Brontis.”

You don’t want to meet Brontis in a dark alley.

Piercing blue eyes. He’s got a certain set of skills.

If you are Alejandro Jodorowsky, and if you’re the producer of this film, having the entire movie mapped out, shot-by-shot, the way they did... That’s the only possible way you get it made. They pulled it off in that sense, just like, “Here’s what this thing is going to be.”

It’s fair because you are really presenting your vision, and it’s honest because if the person that you’re asking to give money or the studio or whatever, if they’re not attuned to that vision, they can look at it and they go, “This is not for me.” No one wastes any time, you know what I mean? When 20 people tell you that, maybe you should start thinking about why it’s not for other humans except for your club of mysteriously wealthy, white male artists and weirdos that you surround yourself with.

But Jodorowsky could have made his movie. He could have hidden his light in a bushel and pitched it and lied and said, “I'll make it in two hours or an hour and a half," gotten the money, and then it’s like so many other movies. It’s just a power struggle between you and the studio. As they pursue their sunk cost fallacy, you keep going. Then you go out to Salvador Dali. Then you go out and commission a weird German mechanical sex artist to create a Harkonnen palace that looks like a guy spitting knives or whatever. That would be the game that you play, but he was straightforward. He was like, “This is my vision.”

With these movies, so much of it is pre-visualization. There is still something that happens when you’re making the movie where you get something you didn’t know you were going to get, and that’s usually in performance. I think the acting in this new Denis Villeneuve Dune is spectacular. What I felt like was that I was just being given the most beautiful rendition of a thousand different ‘70s science-fiction paperback covers that I could possibly imagine, and I would take it all. I would just watch it all day. But I'm not a normal human.

I read the book for the first time over the summer on the beach and had not really been keeping up with developments with the production. Then I looked up the cast. And I was like, "Oh my God. Every role is just the perfect person for this movie.” Timothée Chalamet was born in a lab to play that role. I mean, he’s exactly the strange, introspective, uncanny Paul Atreides that Herbert describes.

Denis Villeneuve is this incredible visual thinker and that extends to not merely the talents of his cast, but the faces of his cast. They all have incredibly interesting faces to look at. Who would’ve known that Dave Bautista is one of the most captivating human heads to emerge from a black stillsuit? It was just incredible and as physically perfect as Sting was in David Lynch’s Dune, he was too beautiful in a movie about deformed people and failures and mess-ups and oddballs. And I mean, obviously Oscar Isaac is gorgeous, but he's got a look of sorrow on his face that works. And Jason Momoa, you just want to look at him all day. Such an interesting face, and luckily they’re all good actors too.

Also Stephen McKinley Henderson as Thufir Hawat. This is a guy who I’d only ever seen on television and in August Wilson productions. He’s an incredible actor and him in his suit, ooh, with his eyes rolling back, his little lipstick. Incredible. I'll watch it all day, and here’s what it gets right. It took me a little while to figure out and get over my disappointment because there are two major characters who are missing from this adaptation. One is Feyd-Rautha, who I never got into in the book. Never cared about. Just dumb. Save him for later. And then of course, there's my very favorite third-stage Guild Navigator. My guy. All I could think about was, “What’s Denis Villeneuve going to do with my favorite penis in a tank?” because you can mutate that any old way.

But then I appreciated that this world is so oddball, you need to dole it out carefully. You can’t do what David Lynch obviously was raring to do, which is show a third-stage Guild Navigator in the opening scene of the movie and expect the audience to be like, “All right, I’m in for this. I was a little thrown off by this glossary, but now that I see that thing…” So you take that third-stage Guild Navigator out. You go easy on the sandworms. You only hint at people riding sandworms a couple of times before, at the very end, you see a guy or a woman way in the distance riding one, and it looks cool. Now you’re saying, “All right, I’ve been here for two and a half hours. I’m bought into all of this.” And rather than have someone just say “Exposition, exposition, exposition, exposition," you sneak that into a little bit of dialogue in the middle of some very stunning visuals and hope for the best.

The other thing that I think that Villeneuve got absolutely right that really astonished me was a really, really clever bit of intuition on his part. If you’re going to tell a story that has a lot of prophetic visions in it—visions that you're going to see and time jumps and hallucinations and so forth—it’s good to remember, as this movie does, that none of the other movies do, that melange the spice is a hallucinogen, and it’s everywhere on this planet. They make that a point of the movie.

They’re basically all just walking around on a giant edible the entire time. And the deeper into the desert they get, the more of this stuff is around and the more Paul starts to become this cosmic entity, and you buy it. Now the visions and the explanatory visions and the visions you’re using as exposition and stuff, they're built into the story in a way. It’s not some ham-fisted narration because you're seeing it, right?

One thing about this Dune is that there’s a trippiness to the book that isn’t a big part of the movie. Is the squareness of this film regrettable in some way?

Even though Paul is inhaling all this stuff out there in the desert and having these visions, you’re right that it’s filmed in a very straightforward way. There isn’t a ton of wild, hallucinatory moments that we associate particularly with LSD, but I felt sensorially completely overwhelmed, and not by the pseudo-trippy parts. There’s something Villeneuve does so well in this movie and perhaps in all of his other movies, where you’ll be looking at a thing and thinking you understand its size and then you will see a human pass in front of it and realize it’s how big it is. And it’s a very trippy experience.

Now I saw it on IMAX, and it’s one of the only movies that I felt benefited meaningfully from being on IMAX. When I see it again, I’m going to see it on a regular good screen and we’ll see how it goes, but the Harkonnen invasion of Arrakeen was monumentally mind-blowing to see. And then in a much quieter moment, when Paul and Jessica and Liet Kynes have escaped to the secret station or whatever, and the Sardaukar have found them and they’re dropping out of the sky silently into the planet station hole or whatever, and they’re tiny, but you just know they’re the seeds of death. It’s just great. It’s interesting that you put it that way because I think this is a movie that Peter Berg would approve of in the sense that it’s stripped away a lot of the psychosexual stuff, stripped away a lot of the weirdness that Jodorowsky and Lynch were chasing. Yeah, that's true. I don’t think it’s square, but I know a square would think it’s cool.

One thing that I think about too—and this is something we can’t know until we see the second part if it gets made—is that both Lynch and Jodorowsky are just fine with Paul being the Messiah. That’s the end of the journey, whereas the most important part of the book for me is that the most likely path that Paul is seeing for himself is a tragic one full of violence and jihad. Do you get a feeling like that is where this Dune is headed?

Well, he has the prophetic vision of the jihad that overtakes the galaxy in his name. One imagines that’s going to be a theme. There is definitely a critique of religion in this movie because this movie acknowledges—and I don’t know if they did this in any of the other Dune adaptations—that the rumor that Paul is the Muad’Dib of the Fremen is whispered into the ears of the Fremen by the Bene Gesserit, and the entire Messianic theology of the Fremen was planted on Arrakis thousands of years ago by the Bene Gesserit. This is their method of social control, to seed mythologies into different cultures. That’s one of the really interesting things about the book because the Jesuits used to just go to the “uncivilized” people and convert them or kill them, right? But the Missionaria Protectiva is very subtle. They just go and they build the myths. It is openly a form of social control. It is a form of being able to manipulate these cultures, which is also what Catholicism is.

It was a very subtle note in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune. It’s just one line, I think, or a couple of lines where Paul says, “I would be fraudulent if I were to accept this,” or something like that. He blames his mom and the Bene Gesserit for being creeps or something like that. But for a critique of religion and phony Messiah stories being seeded to “uncivilized” people, it’s a little undercut by the fact that the guy becomes the Messiah. The novel Dune and all versions of it is a critique of capitalism and what they call a monopoly and control of resources. Melange is oil. That’s what it’s supposed to be. A critique of capitalists, an exploitation of particular resources. It comes to pass that Paul becomes the Emperor and is the wealthiest man in the galaxy at the end of the book.

As a critique of colonialism, and this is where I feel... This is the part of the movie that is unfilmable, but was filmed really well. As a critique of colonialism and exploitation of the people in areas where there are valuable resources, even this movie... This is a white savior movie about a white guy who comes to a brown planet. He’s very much a man. It’s underlined in every version of the story that he’s a man and he’s the only one who can do this. In every version of the story, he is brought into a secret society and led to his fate by his mommy and his girlfriend.

The women are doing a lot of the emotional labor of getting Paul on his way, on the golden path. Paul proves himself to the obviously Arab-presenting and often speaking Fremen by murdering a black man with the skills that he learned in a wealthy person’s castle. There’s a lot of problems here.

He goes through this hallucination in which, right before that fight, he sees himself dying and then he also hears a voice saying, “To kill is to take your own life.” The expectation is built that he’s not going to die, first of all. You know that. But also that he’s going to find a way out of this situation without killing the guy. That would be a big part of any typical movie, heroic journey: I found a loophole in your savage code. But he kills him, and I’m very conflicted about how that image makes me feel. I’m very conflicted about Javier Bardem. I don’t know what accent he’s doing. What’s that supposed to be? Who are the Fremen? I mean, the Fremen are one of countless noble savage tropes that populate genre fiction, and it’s problematic to take that at face value in 2021.

It’s undercut by the fact that Duke Leto knows that the Fremens are fierce warriors and he’s going to make an alliance with them. He sees them as human beings, but the Fremen are still… In the next film, should we get it, we’ll go into their culture more, but the whole white savior boy narrative is not only problematic, we are awakened to its problematism. The sleeper must awaken. I definitely see it better now than I did when I was 14 when I thought all white dudes were the heroes of every story on purpose, because that’s just who we are. Do you know what I mean?

And then I also think it's potentially a problem for the movie, right? What I came out of it thinking was, “Are people going to connect to this?”, because the truth is that Dune is a progenitor of the Chosen One, now stereotype, in countless movies. The original chosen one is Jesus Christ, right? That’s the original one. Hey, guess what? There would be no Star Wars without Dune. Everyone knows this. Not only the desert planet, but also the chosen white boy destined to save the universe or do something big in the universe.

All right. What makes Star Wars a lighter entertainment is that [in the film itself] it is not problematic that Luke Skywalker should become as powerful as he does. It is absolutely true of the book and we hope that in this movie that what Paul sees in his vision of becoming the Chosen One is that he’ll be surrounded by death. That’s a little bit more interesting, right?

You can be Alejandro Jodorowsky if you want, and I’m going to be the bad studio guy [who shoots Villeneuve’s film down like Jodorowsky’s]. What I’m going to say is, “Hey, look, buddy, I love what you’re doing. You made this incredible movie. You’ve been upfront with me. You’ve shown me the movie. I’ll be upfront with you. The story’s incomprehensible for a lot of people, always has been. The chosen one white savior narrative is politically problematic in today’s day and age. I don’t care that you made Liet Kynes into a black woman who dies. It doesn’t make up for everything that’s going on in this story that you’ve inherited from the novel.”

Also, are people going to come to this movie the way people came to the book and go, “This is an incredibly fresh story,” when in fact, it’s also Harry Potter? It’s also Star Wars. It’s also The Matrix. Those are the things I think that would potentially make it hard for an audience to connect and see it in enough numbers that it generates enough revenue to maybe make a second one. But if any version of Dune was going to do it, it’s this one. And I hope that it works, because I think it’s a beautiful film. I’m selfish. I just want to see more. I just want to see more pictures and actors.

I watched Dune in IMAX last night. While I was not handed a glossary of terms at the entrance, I happened to have brought my own in the form of my all-things-Dune loving friend. Our ride home was spent by me asking questions, mostly confirming that I did understand what I just saw. This is all to say, even though this new Dune strips out tons of story and lore and streamlines the narrative, it is still very much a Dune fan's movie. And that's fine. The state of current cinema rewards existing intellectual property that comes with a baked-in audience.

That leads me to something I would love to hear Scott and John's feeling on. I found the PG-13-ness of this Dune to be a bit distracting. There was certainly some artful dodging of carnage. The the more it happened, the more I found myself asking, "Why the hell was this not made to be a hard R movie?" Most of the core audience is adult males who grew up reading the book or watching the Lynch film. I don't get the sense that Denis V. was ever trying to make a crowd pleaser for the whole family. Why not introduce more visceral violence alongside these fantastical images?

So, what do you think--would this be a better film if it was rated R?

A very half-assed defense of Bakshi's Lord Of The Rings: No, it's not very good. But it's ambitious in ways animated films of the era seldom were, and there are intermittent flashes of inspiration. And it was not, as Hodgman implies, a flop; it landed in the Top Twenty grossers for 1978, and did probably as well as a non-Disney animated film possibly could in that very different time. I think the reason it never got a follow-up is due less to lack of studio support and more to the bridges Bakshi burned during its production. By the time it was released, he was already in production on another project. Probably even Bakshi realized LOTR wasn't really his sort of thing.

And hey, if nothing else, at least people remember LOTR as a failed one-off. When they cancelled production on the final entry in the Divergent series, did anyone even notice?