A Conversation with John Hodgman about 'Dune,' Pt. 1

In the first of our two-part discussion on all things 'Dune,' Hodgman talks about his emotionally charged first encounter with the David Lynch film and a Peter Berg version that never happened.

After reading Frank Herbert’s Dune over the summer and seeing the movie earlier this month, I asked myself, “Who do I want to talk all things Dune with the most?” The answer was the author and humorist John Hodgman. I knew Dune the book and the 1984 David Lynch adaptation meant a lot to him, and we’d had many great conversations over the years, including a chat about Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket that we published in the early days of The Dissolve. And because this is our Substack and we can do whatever we want, I talked to Mr. Hodgman for 90 minutes, and, over the next two days, we’re publishing most of the transcript. There’s just too much good storytelling, insight and humor here to leave much of anything out.

For those unfamiliar with John Hodgman, he first emerged in the public sphere when the first installment of his three-part almanac of “complete world knowledge,” 2005’s The Areas of My Expertise, led to an appearance on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, then a recurring role as “resident expert” and a steady career in TV and movies, as well as multiple comedy tours and a 2013 Netflix special called John Hodgman: Ragnarok. He’s perhaps most popularly known for his role as the “PC” in the long-running “Get a Mac” Apple ads. As an author, he completed his fake almanac with 2008’s More Information Than You Require and 2011’s That Is All, and more recently wrote two comic memoirs, 2017’s Vacationland: True Stories from Painful Beaches and 2019’s Medallion Status: True Stories from Secret Rooms.

Currently, Hodgman continues to host Judge John Hodgman, the podcast he’s recorded for 11 years for the Maximum Fun network. He’s also, along with his friend David Rees, the creator, writer, and star of Dicktown, an animated show that’s part of the FXX anthology series Cake. (The first season can be watched on its own on Hulu.) In the first part of our conversation, Hodgman shared his memories of seeing David Lynch’s Dune as a 13-year-old afraid of girls, his feelings about the Lynch version then and now, and a flight where Peter Berg talked about his own plans to make it into a movie. But first, a little Blade Runner talk…

You’re on record as liking Blade Runner. I assume you have a favorite cut?

No.

Really?

I really don’t.

You’re just as fine with the voiceover as without the voiceover?

We always love our first Blade Runner and mine was with the voiceover. I have an affection for it. I saw it on video, so it was probably in ’82, when I was about 11. I probably had my first tweed jacket at that point and was making notes in my Moleskine notebook. And even then I was noting, “This narration is ham-fisted and weird.” But I still have a fondness for Harrison Ford's voiceover, because you can hear how much he hates doing it. It’s so contemptuous. And may I say, robotic?

Yeah, maybe tipping its hand as to-

Perhaps. Although of course, Harrison Ford is mad now at Ridley Scott for saying that his character is a replicant.

I didn’t know that Ridley Scott actually came out and-

Ridley Scott finally came out and said, “Why should there be ambiguity in a work of art? No, he’s a robot.” Harrison Ford heard this news and I don’t remember what his quote was, but the vibe was, “Fuck that. I’m a cool human being. My character wasn’t a robot.”

Well, I guess the most recent version I saw was “The Final Cut,” I think they call it. That’s the one that’s on streaming and it was definitely final and fine. I liked it.

I like the narration not being there, but I don’t think I had that initial investment in the first film that you might have. We’re the same age, but…

Well, you were probably a normal child.

Yeah, I was playing sports. I grew up in small-town Ohio. I was not a city kid yet.

That was not for me. I was in my garret reading Leonard Maltin’s history of animated film and his movie guides and… no one liked me.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

What’s your history with Dune? When did you first encounter it and why did it resonate with you?

Dune has been entwined with my life at significant periods of time in such a pronounced manner that I wonder if an interstellar order of all female monks isn’t seeding it into my life in order to develop me into the most nerdy person in the universe. I first attempted to read Dune while I was in New Haven, Connecticut, for my mom’s nursing school reunion. It was the same summer that Ghostbusters came out. 1984.

The David Lynch movie came out in December of 1984. I was probably trying to read it because maybe I knew that the movie was coming out, or maybe it was my attempt to read science fiction—one of my many attempts to read science fiction and fantasy, which failed because I liked science and liked science fiction and fantasy movies a lot, but I never could dig into the literature per se. And I certainly couldn’t at this time, because at the age of 13, abandoned in the dorm room we were staying in while my mom went and did nursing school reunion stuff, I’m trying to read this book and I’m like, “Oh, I’m sorry, this is boring. I want the spaceship please, but you’re giving me 7,000 words on the drug habits of worms in the desert and a hugely complex, subtle, political drama.”

It was hard for me to follow what was going on, and years later, I’ve now read it at least twice since, probably not in the last 10 years. It’s for grownups. It’s still a fun romp in the desert with worms, but there’s political intrigue. You like that better when you’re a little bit older. It’s a lot more interesting and a lot more followable, especially if you’ve had some measure of education in world history and global culture and so forth. You get more what [Herbert is] going for. But then I went to go see the movie of Dune in 1984 with Tim McGonagle, my friend, who was 14. I was 13 at the time, and it was a profound moment in my life because a couple of memories were shoved into my brain that I will never get rid of. I was very hopeful for this movie, because I liked David Lynch and I was excited that he had made this movie of Dune. And what had he made at that point? Elephant Man, right?

Yes. And Eraserhead.

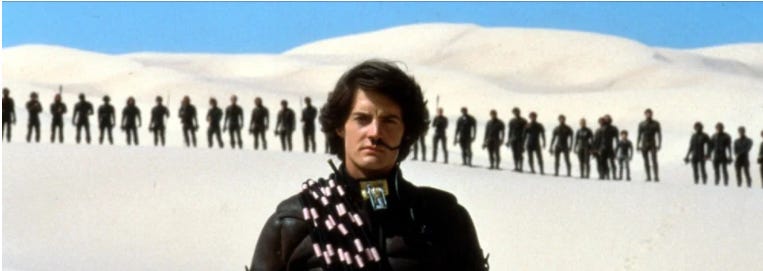

Eraserhead. And by then, I know I’d seen those movies and I was like, “What’s this guy going to do with this book that I couldn’t finish this spring?" I’d been reading about it. There was a lot of press about it, et cetera, et cetera, and I was like, “How can they film a book like this?” Even I, having only read about a third of it, knew this was a bizarre, very interior book that mostly deals with internal monologues from various different characters’ points of view, and what is visually represented in the book is wildly ambitious and also absurd. When you, in your mind’s eye, conjure the image of a hundreds-foot-long sandworm that poops drugs or whatever, this is one of the greatest ideas of all time. When you’re seeing this giant penis on a screen, it looks dumb. And boy did it look dumb in David Lynch’s Dune. It’s hard not to make a sandworm look dumb, right?

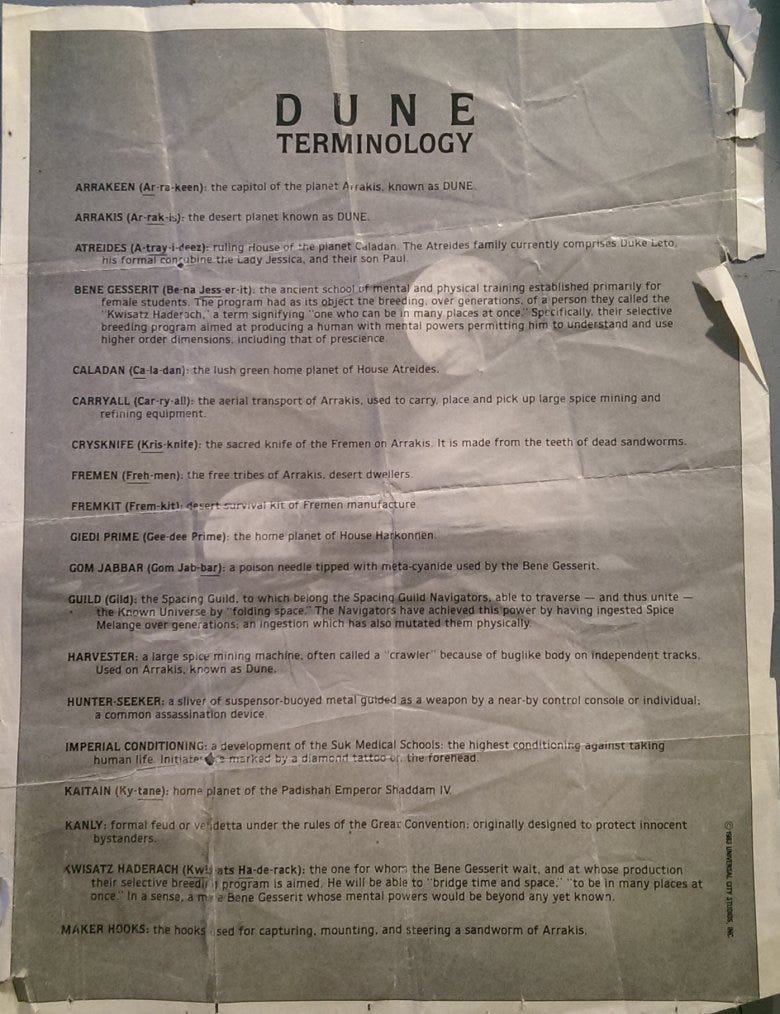

While we were walking into the lobby of the cinema in Brookline Village, in Massachusetts, where I grew up, we were both handed a glossary of terms. This had never happened in a movie before. It’s this little piece of paper saying, “We, the producers think you might want to know a few terms before you go in the theater. The gom jabbar is a poison needle that is held at the neck of Bene Gesserit initiates, but has never been used on a male before. Shai-Hulud is the other name for this giant penis you're about to see.” I’ve caught up with Tim later and we confessed we both looked at this thing as 13- and 14-year-olds and we both had the same instinct, which is like, "This will never work. This is not going to be a good movie.”

But I’m in for it, right? I’ll look at the map of a Tolkien book all day long, but look at who I am. You think regular humans are going to be handed a thing telling them what a hunter-seeker is and then they’ll be, “I'm on board!”? No one wants to do homework. That’s not why you go to the movies. And then the movie happened, but before the movie happened, another thing happened, something so strange it may as well be in the realm of science fiction—which is that a teenage girl sat next to me and talked to me. That was impossible for my brain to process, but it’s true, and I wrote about this in my book, More Information Than You Require. It’s a true story that before the movie started, a girl about my age—and I remember wearing a jean jacket and jeans, the full Canadian tuxedo, and she was on crutches, because I think she had sprained her ankle—sat next to me and then to her right, sat her mother.

And I was listening to their conversation and it turns out, both of them, mother and daughter, love the novel Dune. This was an unusual thing to encounter. I mean, in my experience, women don’t love 1000-page novels about the heroic journey of a white boy, who is the most special person in the universe, who is destined to become the most powerful mind in the galaxy, bred that way by a series of women who are super-talented and powerful themselves, but still need to have a man to do it for them. It’s a sexist book and certainly, the science fiction of that time was really sexist and I knew this, right? This book about a white boy who’s going to become the most important figure in the universe—that’s for me, do you know? That’s for John Hodgman.

And here was this young woman and adult woman sitting next to each other and not only do they love Dune, but they both love Dune, mother and daughter. They have this generational connection to this book and they’re talking to each other about it. I could never imagine. I love my dad, but I could never imagine sitting with my dad in the movies and talking about Dune, right? He’s just a different person. I’ve imagined sitting on the beach with my dad dream-casting the X-Men movie that would never happen because Hollywood would never allow it, as I believed in 1984. That’s what I did with Tim McGonagle.

Here’s a mother and daughter talking about Dune, and I’ll never forget it. The daughter said to the mom, “Who’s your favorite character in Dune?” And the mom said, “I think it’s the sandworms.” I’m like, “What is going on? What an out there take! I love it! Adopt me, please!” And I think that somehow, maybe through melange-induced telepathy, this girl sensed that I was vibing and she turned to me and she said, “Are you looking forward to the movie?” And I said, “Yeah.” And then I said to myself, “Stare at the screen. Do not turn. Do not talk.” Because I was just terrified of all intimacy. And the movie happened, and I experienced the movie entirely through this adrenaline rush of being talked to by a girl, which just didn’t happen in my life, who loved Dune. What should I do about this?

The other feeling I had was, “These sandworms look dumb.” I respect that they might be your favorite character. Everyone likes what they like, but obviously, my favorite character is the third-stage Guild Navigator. He’s this total weirdo who lives in a glass box and no one can touch it. That’s me. I think there is no more shocking and beautiful sequence in cinema than when the second-stage and first-stage Guild Navigators come into the throne room of José Ferrer with mops. They’re wearing black vinyl rain jackets, and they’ve got mops because they’re mopping up the goo that this tank is leaking. And then the thing opens and it’s this giant penis with a vagina that starts talking to the Emperor [Ferrer] about the planets he’s been to.

The Emperor and this penis with its vagina mouth give the exposition to the whole movie because they’re planning out how the Emperor is going to betray the Atreides and take the Harkonnens out of power. Then the Harkonnens will get back in power and all will be right in the Landsraad. And everyone in the theater is like, “What the fuck is the Landsraad?” They’re looking at their glossary. This is a conversation between José Ferrer and a giant penis in a tank and because it’s super secret and whatever, at the end of it, the third-stage Guild Navigator says, “We did not have this conversation. I was never here.” And I was like, “Oh, that’s a great line.” And then his cage closes and they back him out. It’s hard to back those things up.

No, I know.

You can understand why all of this intense sensory input changed my brain and reshaped it to a degree forever. And then of course, after the movie, the girl was in the lobby and she said, “Did you like the movie?” And I said, “Yes,” and I ran away as quickly as possible, though I was aided by the fact she was on crutches. She couldn’t catch up. Got out of that tight situation really easily. I thought about it for years and years and years and years.

About what? About what you might have been able to do differently in that scenario had you had the nerve?

I wanted to have a girlfriend. I just was scared of talking to anybody. And so yes, for the next couple of years, there’s a lot of like, “What could have happened if I had just not been afraid to speak?” Maybe we could be boyfriend-girlfriend. But then years later, of course, it was much more an issue of reflecting upon how scared I was and how almost magical it seemed. I hope she’s doing great. I don’t know what’s going on with her. Never saw her around town again.

But the movie was not good.

It feels like as Lynch’s reputation has grown over time, there has been a little bit more of a Dune apologist contingent out there, with people appreciating a lot of the Lynchian elements in it, maybe blaming the producers for not giving him what he needed to make a better Dune. Where did you end up landing on it, ultimately?

When I say that it was not good, it does not mean that I did not love it, and I loved it right away. It took me a while to appreciate that it’s okay that it’s not good. You can love something, not only for not being good, but also for its failings. It was obvious even to me as a 13-year-old that this was probably not what David Lynch wanted to make. Being handed that card, that glossary at the beginning was basically the studio... I mean, on the other side of the card, the studio should have just written, “We give up.” There was no support. And later, when I would read the book in full, I would realize, “Oh, this is unfilmable,” for all the reasons that I mentioned. It’s a universe-spanning, massive novel about subtle political intrigue and ecology that is told through internal monologue and very little dialogue across multiple different characters.

And it’s got at its heart technology that cannot be put on film without looking dumb. The ornithopters. I mean you can’t have a flapping skycar in 1984. It’s not possible to do it. There’s no CGI. Well, there was Tron. There was CGI, but you couldn’t make that work. Instead, David Lynch gets a little golden triangle with the hint of wings. He did what he could. Giant sandworm, that’s not a technology, but that’s a cuckoo thing to put on screen. In 1984, it’s going to look bad. The triumphant moment when Paul takes his special hook, or whatever, and rides a sandworm… in the book, you’re like, “Good job. I'd like to ride a sandworm too.” In the movie it’s like, “Those bungee cords look like shit and that green screen is terrible.”

And that moment of him and Stilgar high-fiving each other on the back of the... Well, I guess they couldn't reach each other, but winking to each other on the back of this dumb, prosthetic limb, giant prosthetic... Sorry. On the back of this giant prop, it looked dumb. And it was like, “Oh well, David Lynch did what he could and what he did was astonishing,” because obviously he was working in conjunction with professionals in all these departments, but the set design, the costume design, the cinematography, the visuals, were all so unusual for a science fiction film. Beautiful and strange, as strange as the book itself, to a degree. And what is part of the attraction of the book is that it is truly taking us into a far distant future where the cultural stew of humanity has boiled over, been reboiled, distilled, purified, remade.

The frisson of the book is that you have this guy over here, who’s named Stilgar and then you have this guy over here, who’s named Duncan Idaho. How did those two names make it through the 10,000 years of history? The Idaho family? I don’t even think there's someone named Idaho now. It just makes you think about how far distant culturally this is from us and David Lynch made it that alien. He made it that alien. Now we can appreciate that Lynch, like a lot of people, had seen Jodorowsky’s giant storyboarded version of Dune with all of those designs. Unlike that documentary [Jodorowsky’s Dune] which accuses every filmmaker in the world of stealing from it, I would say that it probably gave Lynch license to be like, “Oh, we can have them wearing royal regalia. We can make the world as weird as possible. I can be David Lynch and make Giedi Prime—and this is an anachronism—a fucking steampunk Borg cube full of people in bondage and discipline leather.” You love the movie because everyone in this movie is sexy and deformed and the things that I remembered so distinctly as being Dune. When Brad Dourif as Piter de Vries is approaching the Baron’s throne dungeon or whatever, and he’s drinking the juice of Sapho and he’s saying, “It’s by will alone I set my mind in motion”… It’s this little litany that he says to himself about how he becomes addicted to this juice that gives his mind... “My mind acquires speed. My lips acquire stains, the stains become a warning. It is by will alone and I set my mind in motion.” Something like that. That’s off the dome, by the way. That’s not in Dune. That’s not in the book. David Lynch created that. The other Mentat, Thufir Hawat, being presented with a weird cat-mouse hybrid in a Hawat trail that he’s told to milk? That is not in the book.

The heart plugs as well.

The heart plugs are one of the most disturbing elements of it.

All the Giedi Prime stuff. That’s Lynch. That first scene on Giedi Prime is just such a pure David Lynch scene. It almost feels to me that he had the first reel or two where he could just be David Lynch and then it was like, “Oh shit, I have a huge story I need to squeeze into this tiny amount of time.”

Ten years ago, I would’ve told you, “Even if you had all the time in the world, even if you had two movies to tell this story in, it is still basically unfilmable,” for all the reasons that I gave. It’s not necessary. Do you know what I mean? It’s not necessary. Zack Snyder’s Watchmen is a very faithful adaptation of an incredible work of visual art, and it’s absolutely unnecessary. It is absolutely unnecessary because Watchmen exists as a comic book and uses what only comic books can do, which are still frames that can be obviously duplicated, and you create a Rorschach image of the same frame on either side of the page that are facing each other and you read the visuals that way.

You can't do that with a moving image. It’s not necessary. Watchmen, the TV series, paradoxically, is absolutely necessary because Damon Lindelof and his group mined Watchmen for themes and then created something that was more than just inspired by it. At the end, it falls apart, but so does the end of Watchmen, and becomes something wildly relevant and plays the same visual games that Watchmen did and could, because you could watch the episodes over and over and over again, which I guess you could do with Zack Snyder's Watchmen, but why?

The thing about Dune that’s tricky is that you need a filmmaker who is both capable of doing a classic hero's journey type of movie and also somebody who can give you a hallucinogenic freak-out. You need George Lucas and you need a Alejandro Jodorowsky-type. What director checks both of those boxes?

Well, let me tell you who it’s not: Peter Berg. Because flash forward to 2007 or ’08, I am now completely unexpectedly married with human children. Somehow I made it. That was not foreseen in the prophecy of 1984’s Dune. Very much in love and very happy with my family and completely taken off of my home planet of writing weird little humor pieces for the internet and magazine pieces, I have been thrust into the stars, the Hollywood stars. I get picked to be on the Daily Show and to be in the series of Mac ads in 2006 that completely transforms my life. Suddenly I’m the Kwisatz Haderach out here, the one I knew that I was meant to become, sitting in first class on an airplane to fly to Los Angeles to film something, probably one of the ads.

Seated next to me is Peter Berg. He comes on the plane late. He sits down, throws his leather knapsack down. Now I know Peter Berg at that point as Billy Kronk from Chicago Hope and that guy in that weird time capsule movie that I watched when I worked at the video store in college called, I think, Late for Dinner. I didn’t know that he had done Friday Night Lights. What do I know about Friday Night Lights? I’m not going to watch that. It’s sports. My wife loves Friday Night Lights so much, and she says the same thing to me that everyone who loves sports says to me: “It’s not about the sports. It’s about the stories.” And I’m like, “You love what you love, but you know that there are stories. I don’t need the sports to get the stories. Look at all these books. Look at all these movies. Those are about stories, too. I don’t want to see a bunch of jocks, okay? I’m a nerd.”

Jocks with feelings mess up my worldview. Then I have to acknowledge they’re whole human beings and I have to have a reckoning. They’re not just bullies or whatever. I don’t need that. I made a deal with my wife, who is a whole human being in her own right. I said, “Well, if you will read the first Game of Thrones book, A Game of Thrones, then I will watch all of Friday Night Lights.” And she said “Deal.”

There is no book more readable than A Game of Thrones. It's just... “Brrrrrr.” [mimes flipping pages] You eat it up. It’s great. But she was 100 pages in. She gave it 100 pages. She’s like, “Sorry, deal’s off. I’m not going to read about this.” And I’m like, “Of course. Great.” Some people just don’t have the RNA receptor for certain kinds of culture. This doesn’t hit your brain in the right way. Exactly. Friday Night Lights, it doesn’t hit my brain. Same thing. I can’t help it that I love Tom Waits and Bob Dylan does nothing for me. These are embarrassing positions to have, but I love Tom Waits and I’ll take his “Jersey Girl” over Springsteen’s every day. Sorry.

Anyway, Peter Berg sits down, and I know who Peter Berg is, right? We’re stuck on the tarmac. We can’t take off for a long, long, long, long time. It’s getting to be a real drag. Peter Berg finally decides, “Okay, I've got to read something," reaches into his bag and pulls out a copy of Dune. And at this point, I’ve grown up a little bit. I can talk to people who are sitting next to me. I was going to respect his silence, but I could not control myself and I said, “Man, that’s amazing. I wish I had a copy of Dune to read on this flight.” And Peter Berg said, “Do you want one? I’ve got two.”

I’m like, “What are you talking about, Peter Berg? Why do you have two copies of Dune?” He said, “Well, because I’m thinking about making it into a movie.” I mean, he said it with such Peter Berg-y jock-y confidence that I actually had a moment where I was like, “Does he not know? Does he not know that there was a movie?” Because he was like, “I’m thinking about turning this book into, get this, a film.”

And not only was there a movie, but at that point, there had also been a mini-series on Sci-Fi channel in the year 2002, two of them. It had been adapted already. Am I going to be the guy who has to tell Peter Berg that David Lynch already made a movie of Dune? But he knew. He knew. And as we got to talking about it, he knew, and he was saying, “Look, this is a classic hero’s journey about a chosen child who must heed a call to adventure and all this Joseph Campbellian stuff.” And then Peter Berg, being the artist that he is, takes out a spreadsheet and points out the top-grossing movies of all time and he’s like, “Chosen one narrative, chosen one narrative, chosen one narrative, chosen one narrative.” I’m like, “Yeah, I get it Peter Berg. White guys love to see movies about white guys who are the chosen special ones."

Basically, Peter Berg’s take on Dune was that he was going to focus on the adventure and the warfare and a little bit less of the psychosexual stuff.

That is not shocking.

Yeah. He was like, “David Lynch made his version.” I don’t want to put words in Peter Berg’s mouth, but he was like, “I’m going to make this a guy’s movie, not a weird guy’s movie.” And so I was like, “Well, good luck to you.” And not long after that... We had another long conversation. We talked and talked and talked the entire time. I still don’t believe I left any impression on him.

I think it was just a coincidence that Peter Berg was still trying to find a screenwriter, and I had written a screenplay that didn’t get produced. No one made a documentary about [my screenplay]. Boy oh boy, Alejandro Jodorowsky. Wow. I’m sorry your thing didn’t get made. Seems like you and your friends had a lot of fun and spent a lot of money talking about your dreams and stuff. That’s a pretty good deal. It’s a pretty good outcome. Sorry the movie didn’t get made. It happens. It’s not a condemnation of reality.

That was an interesting movie, Jodorowsky’s Dune. My favorite part is when [Jodorowsky] is so mad at the studios. He’s brilliant. He’s a wonderful guy. I love him and his son. “I had a great idea of who to cast in this movie: My son.” Wow. All right. I believe you. He worked this whole thing around Salvador Dali’s insistence on being paid $100,000 an hour [to appear in the never-realized Dune adaptation]. Actors exist. You don’t need to... This is your journey. This isn’t important for a movie. You want to meet Salvador Dali. I get it. Somebody wanted Sting to be in David Lynch’s Dune. David Lynch probably said, “I don't know why. Actors exist.” No, no, we wanted Sting to come out of a steam bath and look really ripped. It’s an incredible scene.

Anyway, I had written a screenplay that didn’t get made, but I was being thought of for things, and someone called me and my manager called me and said, “They're looking for a writer for Dune and would you like to pitch them?” And I’m like, “Hmm. Wow. Well, I have two problems with that. One, I think the book is unfilmable, but who cares? Two, is Peter Berg directing it still?” And they’re like, “Yeah,” and I’m like, “I don’t think it's going to work. I don’t think that jock is going to like this nerd, because the only thing I like about the previous movie is the heart plugs and the weird stuff.” That’s why I declined to work with Peter Berg and he later dropped out.

Tomorrow: John Hodgman on Denis Villeneuve’s Dune.

I am loving this conversation, and particularly that Peter Berg story.

My dad told me that the 1984 Dune was the first movie he and my mom went on a date together to see and I can't stop thinking about that.