Worst to Best: Éric Rohmer’s Tales of the Four Seasons

The auteur's quartet of '90s films recently resurfaced in restored prints on The Criterion Channel. They're all great, but we decided to rank them anyway.

When asked by Sight and Sound in 1971 about the origins of his first series of films, The Six Moral Tales, director Éric Rohmer offered an explanation that mixed artistic concerns with practical matters. The series came about, Rohmer told journalist Rui Nogueira, “[p]artly because I wanted to follow the same idea through several films and partly because I thought audiences and producers would be more likely to accept my ideas in this form than in another […] by the sixth time the audience would come to me.” It might seem odd to talk about Rohmer — known for his spare style, veiled private life, and a Catholic faith that put him out of step with other, younger members of the French New Wave — as a pioneer of franchise filmmaking, but he knew what he was doing. It didn’t take six films for the audience to find him. His first feature, La Collectioneuse, won acclaim in 1967. Its followup, My Night at Maud’s, became a worldwide arthouse hit two years later. Their successors had the advantage of being linked by association.

Rohmer completed the Moral Tales in 1972 with Chloe in the Afternoon and more series followed. The filmmaker released six films under the Comedies and Proverbs heading 1981 and 1987, including some of his best-known, best-loved films, like Pauline at the Beach and The Green Ray. But his final series, Tales of the Four Seasons, has been harder for North American viewers to appreciate, if only because they were so hard to see. Released elsewhere in 1996, A Tale of Summer didn’t arrive in the U.S. until 2014, four years after Rohmer’s death at the age of 89. Its companions played theaters but anyone wanting to watch them in recent years had to track down out-of-print DVDs.

That changed last month, however, when all four Tales of the Four Seasons — A Tale of Springtime (1990), A Tale of Winter (1992), A Tale of Summer (1996) and A Tale of Autumn — appeared in restored editions on The Criterion Channel. Each is (largely) set within the the season of its title and each contains a story thematically appropriate to its moment in the year. Each is also unmistakably a Rohmer film, filled with soulful, beautiful, often frustrating characters prone to engage (usually against the backdrops of some of France’s most striking vistas) in lively and probing philosophical conversations that circle around the big question that’s rarely spoken out loud: “Should we be sleeping together?” (The emphasis can fall on the first or second word of that sentence, depending on the characters and their situation.)

All are excellent, and very much worth your time. But does that mean they can’t be ranked? Of course not. So let’s put these Tales of the Four Seasons in some kind of order (followed by a bonus seasonal ranking just for fun).

4. A Tale of Springtime (1990)

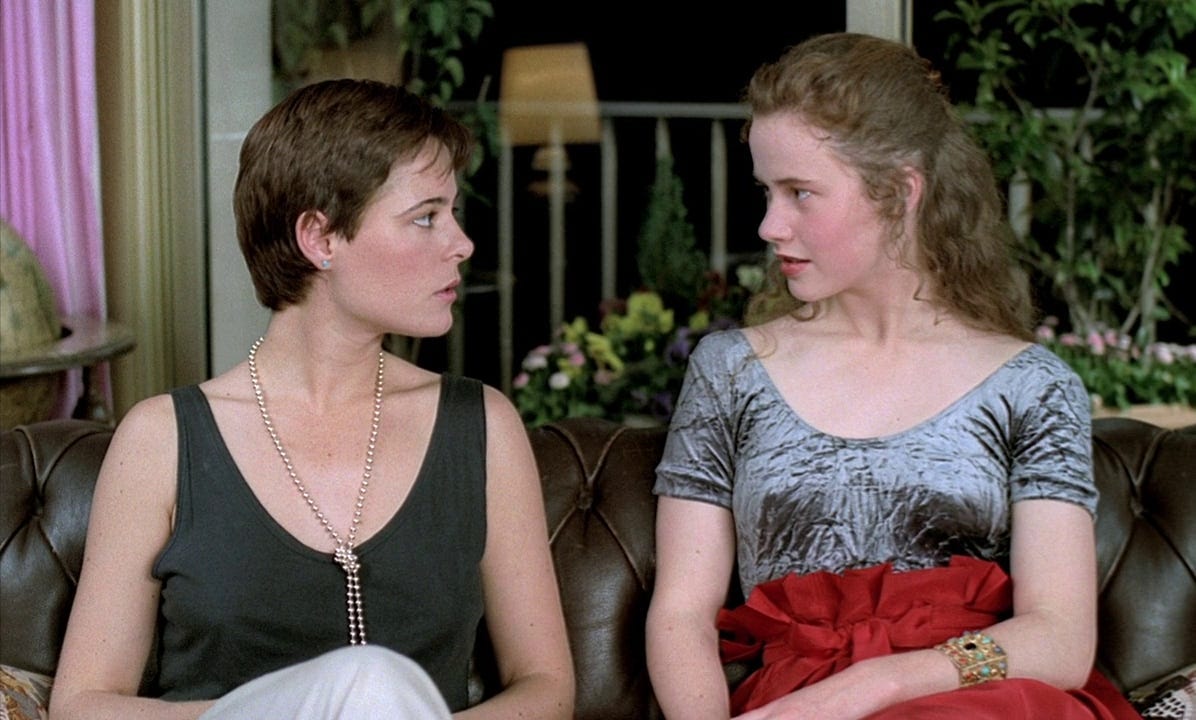

Unable to sleep in the apartment she’s lent to her cousin and reluctant to spend the night alone in the messy flat she usually shares with her boyfriend, Jeanne (Anne Teyssèdre), a professor of philosophy, attends a party where she meets Natacha (Florence Darel), a younger, high-spirited pianist who invites her stay at her place. There, Jeanne learns of Natacha’s distaste for Eve (Eloïse Bennett), her father Igor’s (Hugues Quester) young girlfriend, and comes to realize that Natacha is trying to throw Jeanne in her father’s path.

Conversation drives A Tale of Springtime but, as is often the case in Rohmer films, Rohmer’s images do as much work telling the story as his words. Why doesn’t Jeanne want to stay at her boyfriend’s place? Why would she when it’s so cluttered and shadowy compared to every other location in the film, particularly the summer home where she and Natacha travel to do some gardening as nature wakes up from its winter sleep? And while every exchange she has with Igor when left alone with him feels like an attempt to push him away, why do they look so natural sitting next to one another when he asks to join her on the couch?

A collection of minor moments that push its protagonist toward making a major decision, A Tale of Springtime sets the pattern the other Tales of the Four Seasons would follow. Like its successors, it mixes wry humor with a sense that we’re watching characters make choices that could set them up for a happier future, leaving them wondering what might have been or, just as likely, both.

3. A Tale of Autumn (1998)

Magali (Béatrice Romand), a widowed winemaker in her forties, laments to her best friend Isabel (Marie Rivière), a happily married bookseller, that she’s become lonely without romance in her life. To correct this, Isabel takes out a personal ad and begins meeting with a man named Gerald (Alain Libolt) while posing as her friend. Separately, Rosine (Alexia Portal), the girlfriend of Magali’s son, attempts to set Magali up with Étienne (Didier Sandre), a professor and, until recently, Rosine’s lover.

Rohmer’s films almost always focus on younger characters, which he once told the French newspaper Libération was the result of an abiding interest in subjects whose “roots go back to the period of my own youth.” Though it doesn’t suffer from a shortage of younger characters in supporting roles, A Tale of Autumn is an exception, exploring the possibilities of mid-life romance against the backdrop of a grape harvest and much talk of the pleasures of wines that age well. Farcical in construction and whimsical in tone, its lightness is balanced against Romand’s remarkable performance as a vibrant, resilient woman nevertheless threatened to be consumed by melancholy.

2. A Tale of Summer (1996)

A young mathematician with musical aspirations, Gaspard (Melvil Poupaud) has opted to spend the summer in seaside Brittany, lured by the possibility he might reunite with his sometime girlfriend Léna (Aurelia Nolin). There he meets Margot (Amanda Langlet), an ethnologist researching the culture of the region when not working as a waitress. They begin spending their days together and their closeness sometimes erupts into episodes of romantic tension, which doesn’t stop Gaspard from also pursuing Solène (Gwenaëlle Simon, an acquaintance of Margot who takes a liking to him).

A Tale of Summer begins with a long, wordless stretch that captures the isolated feeling of being friendless in a strange place, however beautiful it might be. It ends in chaos, albeit chaos of the low-key sort that might be expected of a Rohmer film, as Gaspard tries to navigate a situation in which too many women are demanding his attention at once. Though, if anything, even less dramatic than A Tale of Springtime and A Tale of Autumn (it depicts a long summer with a lot of aimless strolls, lounging around, and waiting for phone calls that may or may not happen), the film feels weightier than those seasonal companions. Whether he recognizes it or not, Gaspard has reached a turning point and the choices he makes as summer draws to a close will have profound implications on the rest of his life. Rohmer is a master of final scenes that subtly and unexpectedly reveal the significance of all the moments leading up to them, and this one packs a wallop.

1. A Tale of Winter (1992)

A Tale of Winter concerns Félicie (Charlotte Véry), a woman who ends a summertime fling with Charles (Frédéric van den Driessche) by accidentally giving her lover an incorrect address, making it impossible for him to find her. (Though set in the not-that-long-ago 1990s, these films provide constant reminders of how much technology has changed the way we communicate with one another.) Flash forward five years and Félicie is a single mother to a son who knows his father only as the smiling guy in a photo. Félicie spends some nights with Loïc (Hervé Furic), an attentive librarian, but makes plans to move to the city of Nevers with Maxence (Michel Voletti), her boss at the hair salon where she works. It’s, for many reasons, a smart choice. So why does her heart tell her it’s the wrong one?

Why does A Tale of Winter top this list? Each of the Four Seasons films are outstanding but none contains a moment quite as breathtaking as a mid-film scene in which Félicie accompanies Loïc to a performance of Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale (a play’s whose title, of course, echoes the film’s). The performance’s final moments reflect Félicie’s own state in ways that she couldn’t have anticipated, prompting her to reexamine her life. Rohmer effortlessly weaves his abiding concerns with earthly love and religious faith into a story that’s as humble as it is miraculous — and one that captures the way art can illuminate and change the lives of those it touches.

Bonus Ranking

The Four Seasons (as experienced in real life)

4. Winter

One week of winter is great. Then the novelty wears off. The cold, the snow, the isolation. Who needs it? Whether it’s the seemingly endless winters of the Midwest or the dangerous deep freezes of even colder climes, winter is obviously the worst.

3. Spring

Yes, spring brings a sense of reawakening but it can be a little too tentative. It’s a good season, but one with the potential to combine the worst of parts of winter and summer while covering it all in rain.

2. Summer

The relaxed pace, the warmer temperatures, the long days and nights that invite lingering under the starlight: summer has a lot to recommend it. Yes, it can be too hot, sometimes oppressively hot. But still, summer’s tough to beat unless you’re…

1. Autumn

A time of crunching leaves and light sweaters as the first, crisp hints of the colder months that remain safely in the distance tame summer’s excesses: autumn is obviously the best.

I was expecting Keith's actual season ranking to draw more fire here. Are summers too oppressive now for the #2 slot? I tend to agree with him all around here, but that might be Chicago talking. Feels like winter hangs around too long into spring here-- though it's gorgeous today-- and September/October is when everything is set right.

I saw “Autumn” on the big screen. It plays better there than on TV