Who Was 'Darkman'?

The summer after 'Batman,' director Sam Raimi made his major-studio debut with a modestly budgeted, original superhero movie. We wouldn't see its kind again.

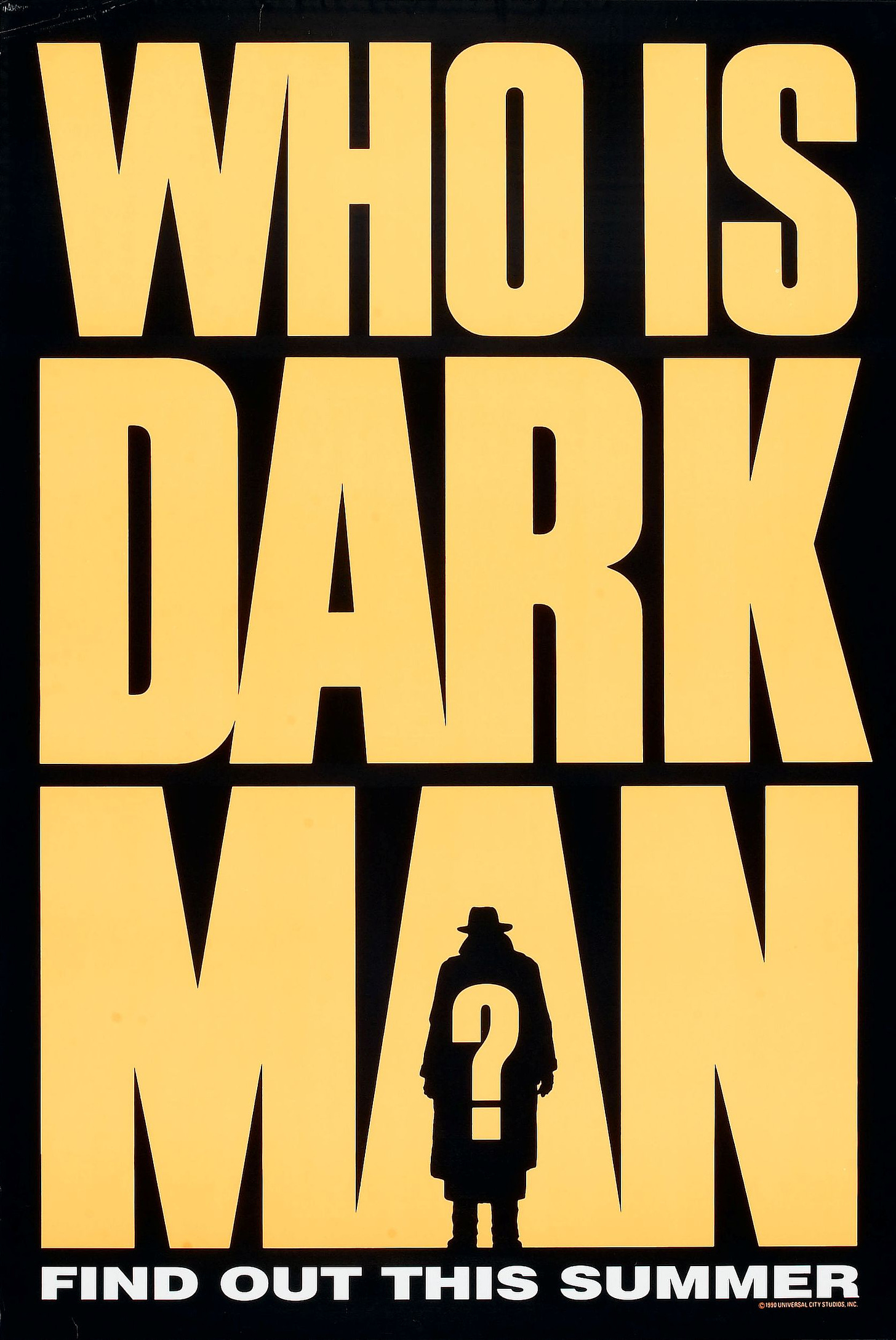

“Who is Darkman?”

That was, incredibly, the question on everyone’s lips in the late summer of 1990, when blockbuster season had wound down and kids were going back to school. At the time, I was working my last month at a movie theater before leaving for college in the fall, and our competitor, which had booked Darkman, had long displayed the teasing poster, kind of the last-poster-standing after other films had opened in more optimal weekends. For audiences in the dog days of summer, there was no other choice than to scratch this weird little itch: The previous #1 movie in the country, Ghost, had been out for seven weeks, and the August 24 new-release competition was weak, with the Emilio Estévez comedy Men At Work opening alongside the second Delta Force and Nicolas Roeg’s dark (though excellent) adaptation of The Witches. Darkman’s release proved a small masterpiece of scheduling and marketing, leading to a first-place, $8 million opening weekend and a tidy little profit for Universal Pictures.

None of that would be possible now. Not a single detail. Major studios are not in the business of making tidy profits anymore. They’d rather dig deep into the Marvel or D.C. catalog—hello, Eternals—before rolling the dice on an original superhero. And even then, Universal wasn’t risking too much, as Darkman cost a fraction of what other putative blockbusters did, which is the only way they hand the reins over to Sam Raimi, whose most notable credit at that point was a low-budget slapstick horror-comedy with POV flying eyeball shots. Thirty-two years later, Raimi has tried to bring as much as himself as possible into Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness, a Marvel sequel that may owe more to his Evil Dead series than Darkman, but nonetheless represents a pitched battle between a director with a distinct style and a machine-tooled franchise that tends to bring filmmakers to heel. Truly, Darkman feels like it was made several lifetimes ago.

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

In truth, Universal was doing what risk-averse studios have always done: Following the trends. The summer of ’89 was the summer of Tim Burton’s Batman, and Darkman was only the first of a number of mid-budget attempts to capitalize on that smash, soon followed by The Shadow, The Crow, The Phantom, Judge Dredd, Barb Wire, and Tank Girl. It was a higher-priced version of what producers like Roger Corman did after the Jaws phenomenon in 1975, when other underwater threats like piranha (Piranha) and alligators (Alligator) and orca (Orca) turned murky seas into the new haunted houses. In retrospect, it seems fitting that Raimi’s passion for Universal monster movies and Looney Tunes aligns him so closely with Joe Dante, whose Piranha was such an ingenious Jaws riff that the director Dante was aping, Steven Spielberg, hired him to make his studio debut with Gremlins. The keepers of the genre flame now had run of the backlots.

So who is Darkman? He’s a masked urban avenger of the Batman school, certainly, and the film’s score, by Danny Elfman, is close enough to the one he did for Burton to firm up the connection as early as the opening credits. But there’s much more to him than that: He is Frankenstein’s monster if the monster were actually Frankenstein, created in a lab with the requisite beakers, bunsen burners, and flashes of lightning and fog. He’s also a freak inspired by Phantom of the Opera and The Elephant Man, driven to near-madness by a disfigurement that keeps him in the shadows and inside his own head. Strength is his main superpower, but his inability to feel physical pain is another, more complicated condition—his curse is that, excellent as he is in combat, his psychological pain is magnified. He’s held captive by his own emotions.

Liam Neeson stars as Dr. Payton Westlake, likely an homage to the pulp writer Donald Westlake. The doc’s working on synthetic skin grafts that will revolutionize the treatment of burn victims, but there’s a sticking point: the grafts lose their stability after 99 minutes, when the cells start to break apart and turn the skin into what looks like the melted wax of a giant candle. In a “Eureka” moment, Westlake accidentally discovers during a power outage that the synthetic skin is photosensitive and will last longer than 99 minutes in the dark. Meanwhile, his girlfriend Julie (Frances McDormand), a crusading attorney, has found a memo incriminating a powerful developer (Colin Friels) for bribing members of the zoning board to build his “city of the future.” Tracking down the memo, Robert Durant (Larry Drake), a sadistic gangster, bullies his way into Westlake’s lab and blows it up, destroying the research and presumably Westlake himself.

He’s not dead, of course, but he’s been disfigured to the point where he’s labeled John Doe at the hospital and then used as the guinea pig in an experimental treatment that severs the nerves that allow him to feel pain. The procedure endows him with tremendous strength and pushpin invulnerability, but also a mental instability that puts him at war with himself. He’s still Payton Westlake, the rational and sensitive man of science, but deprived of normal human inputs, his emotions are overwhelming, heightened by his total alienation from Julie and society at large. When Raimi would later shepherd Doc Ock (Alfred Molina), the greatest of all Spider-Man villains, to 2004’s Spider-Man 2, the greatest of all superhero films, there was plenty of Darkman DNA in the character. The difference is that Westlake never succumbs to his turbulent feelings, at least not fully.

In 1990, Neeson was largely unknown, buried deep in the cast lists for films like 1984’s The Bounty and 1986’s The Mission, but still a few years away from breaking through as a leading man in Schindler’s List. His particular set of skills at the time were a unique combination of imposing height and great sensitivity, a gentle giant who would look genuinely intimidated by tiny Mia Farrow in Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives in 1992. In contrast to Batman, whose tragic childhood is mitigated by Bruce Wayne’s privilege and playboy lifestyle, Westlake is a truly melancholy avenger, torn apart by the tug-of-war between his rational and irrational mind. Drake’s Durant proves a delectably nasty heavy, with his yen for clipping fingers with a cigar-cutter, but Westlake remains his own worst enemy.

Tonally, Darkman is as expansive as its hero’s emotional spectrum. A scene where a stressed-out Westlake, wearing a synthetic Neeson skin mask that’s close to the end of its 99-minute life, tries to win a pink elephant from a carnival game booth is desperate, absurd, and hilarious all at once. He wants to win over Julie, who still can’t believe he’s alive and can’t get a feel for who he’s become, but this carny won’t give him his prize because he has (quite literally) stepped over a line. In Raimi’s hands, this psychic breakdown cracks open reality like a volcanic eruption, leading Westlake to snap the carny’s fingers while watching himself in horror as he does it, as if Jekyll and Hyde could be conscious for the same moment. The sight of Westlake dashing away to his warehouse lair with his skin smoking and the plush elephant under his arm, crying like a small child, is the film’s funniest and most pitiable image.

Beyond the pathos, though, Darkman is delightfully unhinged for a studio movie, boasting many of the zany camera tricks that Raimi had deployed for Evil Dead II three years earlier. In an oral history of the film for The Hollywood Reporter, cinematographer Bill Pope said, “We used the eyeball/flyball rig, the Perfalock dance-o-cam, the Perfalock drunken cam, snap zooms, whip pans, Dutch angles, cameras attached to sticks and blankets and virtually anything that moved.” The cartoon-y style extends to the supporting characters and dialogue, too, like a henchman who hops around when his prosthetic leg is being used as a machine gun, or a gravedigger who talks about how it was to bury Westlake, because all they found was a tiny piece of ear.

As some fret over how much mayhem should be allowed in the resolutely PG-13 MCU, maybe we should be worrying more about what types of studio movies are now allowed to exist at all and what possible paths a young director of Raimi’s sensibility might take through the current system. There’s a place for off-brand superheroes now, just as there was for the cut-rate, often enjoyable drive-in versions of Jaws. Yet asking for a modest, offbeat studio original like Darkman seems like asking for the moon. The message implied by Raimi’s Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness is deflating: If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

I once played an all-movie edition of Team Trivia at a local watering hole. The halftime entry was "Name four of the [then] five movies where Liam Neeson played the title character." The Emcee that evening went out of his way to say that "one team wrote down 'Darkman,' which is correct." That's still high among my accomplishments of playing team trivia back in the day...

I remember seeing this one in theaters and no really knowing what to make of it (pretty sure it was my first Raimi). Definitely need to check it out again. On a related topic, I couldn't agree more with Scott that Spiderman 2 remains THE definitive comic book movie.