What Happens When You Cut Six Seconds Out of ‘The French Connection’?

A slightly shorter version of William Friedkin's 1971 classic is now the only version available to stream in the United States. The cut changes the film at a fundamental level.

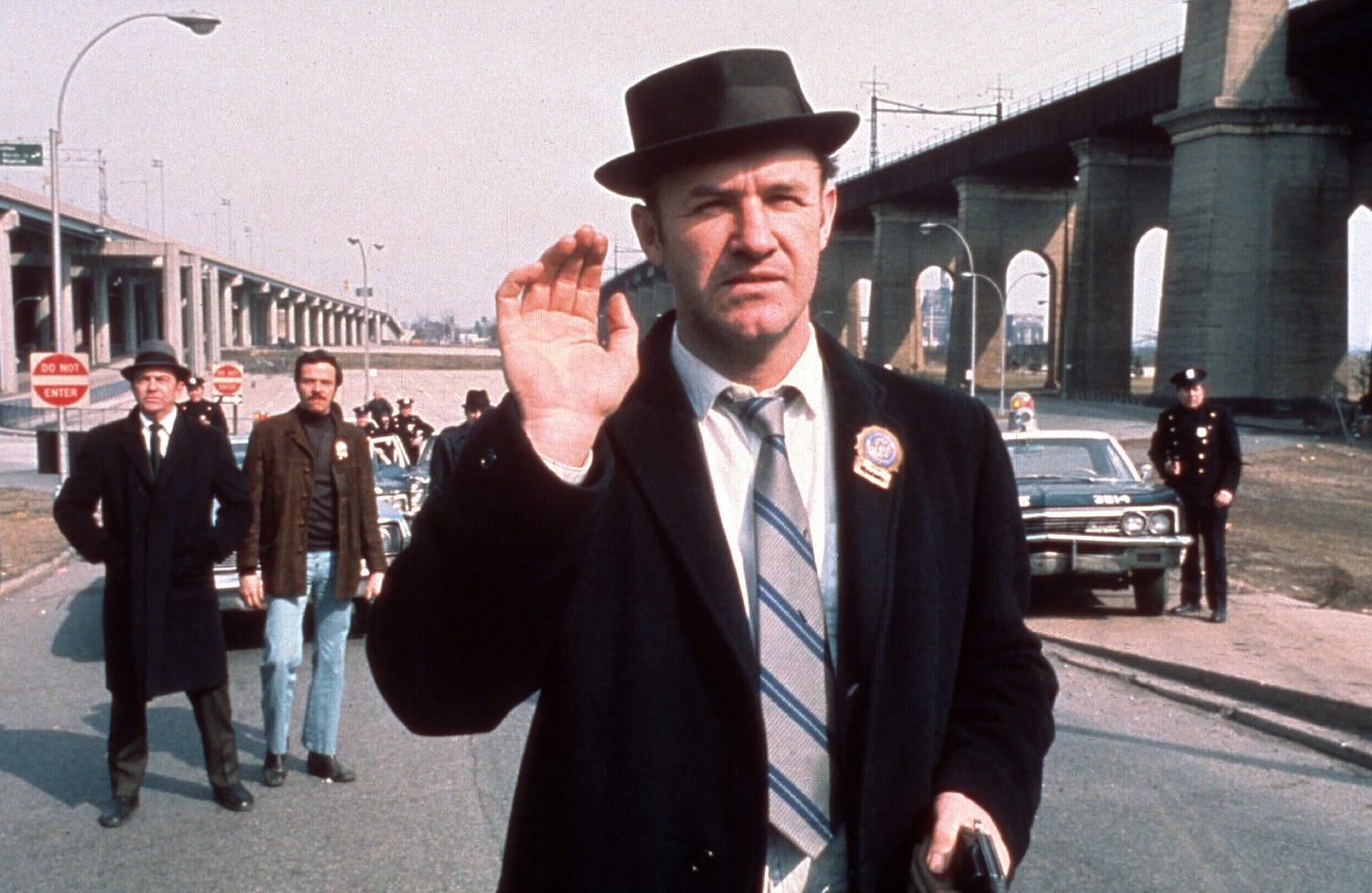

Earlier this month, viewers of William Friedkin’s 1971 classic The French Connection who’d seen the film before noticed something missing from the version streaming on The Criterion Channel and available to rent and purchase digitally. Within those six seconds, an exchange between the narcotics cop Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) and his partner Buddy Russo (Roy Scheider), Doyle uses the n-word. In the new cut, he does not. It’s a few lines of dialogue that, when removed, fundamentally change the film.

The change remains unexplained, though the prevailing theory that the cut was made by Disney, which acquired the film as part of its purchase of Fox in 2019, seems pretty sound. It has, understandably, provoked outcry, as any change to a classic film invariably does. And some of the complaints have been opportunistic and misguided. Without engaging in the substance of the film or the cut in any way, The National Review predictably dubbed it “the latest victim of woke corporate censorship.” In a curious piece for The Atlantic, Thomas Chatteron Williams finds some solid ground, then wanders into weird terrain as he uses the incident as a chance to suggest that erasing ugly examples of racism from the past is dangerous because:

There is a strange comfort in believing that the world does not change and that the struggle against racism and other forms of oppression is never-ending. The depravity of previous eras is wiped away and, with nothing to compare it to, we proceed to believe that our contemporary traumas are equally significant.

Without scenes like these, Williams’ logic seems to go, people will never understand they’re complaining way too much about the way things are today.

It’s not hard to see Disney’s logic behind the cut, assuming Disney is indeed responsible. This moment might disturb some viewers. It’s only six seconds. Are those six seconds really worth the complaints and hassle they invite? And the issue of how to deal with potentially upsetting material from the past isn’t one with clear rules that can be applied to every instance. Context is everything: a racist character using a slur in The French Connection isn’t Song of the South, which isn’t Gone With the Wind, which isn’t Fred Astaire wearing blackface, which isn’t Blazing Saddles, etc., etc. But this provides a pretty great example of how not to deal with it.

That’s partly because it’s so clumsily done, introducing a jerky cut into what’s otherwise a beautifully edited film. (Gerald Greenberg even took home an Oscar for his work.) But it’s mostly because the moment is key to understanding Doyle and the tension at the heart of the film, which asks viewers to stay side-by-side with a character they know to be deeply morally flawed on an obsessive and violent quest to take down an international drug ring. Whatever good he might be doing, Doyle is not a good person. And, more specifically, he’s racist.

Doyle’s racism is evident from the start of The French Connection, which introduces him posing as a sidewalk Santa and entertaining some Black kids before springing into pursuit of a low-level Black drug-dealer named Willie being chased by Russo, who’s cut on the arm after cornering the criminal. When the cops catch Willie, they both beat him, but it’s Doyle who takes it too far in his partner’s eyes. Russo begs Doyle not to kill Willie, then pushes him away as they continue their rough interrogation.

Doyle behaves like a man driven by factors beyond the desire to get his man, but it’s in the now-cut exchange that follows that makes what’s been implicit explicit. Talking to Russo at the station, he calls Russo a “dumb guinea.” “How the hell did I know he had a knife?,” Russo replies. Then Doyle says, “Never trust a ___.” “He coulda been white,” Russo says, to which Doyle responds: “Never trust anyone.”

In the most ludicrously generous reading, Doyle is someone who throws around slurs freely, hence the “guinea” label. But that’s not what’s going on here. Doyle is a cop who takes sadistic pleasure in beating Black suspects and who views the city he’s supposed to protect through a lens of bigotry. He can be chummy with a Black informant but still makes a point of ending their meeting with a vicious punch to keep the informant’s cover. (Though Doyle at least offers him the courtesy of choosing where he wants the punch.) The absent moment removes any doubt about who Doyle is in the original, uncut version of the film. Removing that epithet gives Doyle the benefit of the doubt. Maybe he just plays rough.

Friedkin knew what he was doing. His early work included the documentary The People Vs. Paul Crump, which helped lead to a Black death row inmate, who claimed to have been tortured into confessing by the police, having his sentence commuted. (Made for Chicago TV, it was deemed too controversial to air in 1962, but Friedkin brought a copy to Illinois governor Otto Kerner.) He bakes ambiguity about the job of policing into the film. Screenwriter Ernest Tidyman knew what he was doing, too. A journeyman journalist, he’d scored a big hit the previous year with the novel Shaft. Tidyman was white, but both the novel and its film adaptation (which appeared the same year as The French Connection and which Tidyman co-wrote) freely depict racial inequality.

The moment’s removal has a cascading effect. If Doyle becomes just a rough-and-tumble cop with no particular prejudices, the revelation that the city’s drug trade mostly benefits rich, white criminals loses its impact. The film’s famous chase scene gets cast in a different light, too. Over the course of Doyle’s pursuit Nicoli, the sniper who tried to kill him as Doyle was heading home, Nicoli kills a Black cop and his actions lead to the apparent death of a Black train operator. When a group of subway riders tries to overpower Nicoli, many of them are Black as well. That the people Doyle disparage suffer as he attempts to do his job adds another layer to the sense of futility that hangs over the entire film, particularly in its final moments, when Doyle accidentally kills a fellow cop who’s been critical of his methods from the start and a series of text screens reveal how little the bust accomplished. In the end, was any of this worth it?

This subtext didn’t go unnoticed in 1971. Critics and commentators openly referenced Doyle’s racism as central to his character. “Popeye is in it for fun. For the giddy pleasure of busting people and busting heads, of rampaging into black bars and snarling racist obscenities,” Giles Fowler wrote in a typical review for the Kansas City Star. “Doyle himself is a bad cop, by ordinary standards,” Roger Ebert echoed in the Chicago Sun-Times. “He harasses and brutalizes people, he is a racist, he endangers innocent people during the chase scene (which is a high-speed ego trip).” Without Doyle’s use of a slur, these claims of racism would look shakier. There are plenty of moments that suggest Doyle’s racism, but only one that makes it undeniable, bringing the film into sharp focus in the process.

You won’t find that moment in the only version of The French Connection currently available via streaming services in the United States. It’s not even a less offensive film now. Removing the racial epithet introduces an ambiguity to Doyle’s behavior that ultimately turns a film once defined by its awareness of racism into, well, kind of a racist film. Somebody has snipped six seconds from the film. But they took away a lot more than that.

Advantage: Real-medium pack rat. Long live old DVDs and their brethren...

Is (presumably) Disney going through the whole Fox catalog and making cuts like this? Have any other examples been spotted? I’d like to see an investigative piece about it all.