Wes Anderson in the Land of Dahl

The filmmaker's new series of Netflix shorts find him merging his vision with Roald Dahl's work while pushing a familiar style in unexpected directions.

It’s vile, what the Rat Man (Ralph Fiennes) does to demonstrate his skill in “The Rat Catcher,” one of four new Wes Anderson-directed short films adapting Roald Dahl stories that premiered on Netflix last week. While speaking to the unnamed editor (Richard Ayoade) of a small English town’s newspaper and Claud (Rupert Friend), the proprietor of a petrol station, the Rat Man pulls a rat out of one pocket and a ferret out of another. “Nothin’ will kill a rat quicker than a ferret,” the Rat Man says. Then, to demonstrate, he places both inside his shirt. The detached, distant look in the Rat Man’s eyes as the commotion rages against his torso is the most disturbing detail of all.

True, Anderson doesn’t actually show the ferret or the rat (not that rat, anyway, though another makes an appearance a bit later). Instead, while the Rat Man stares into the camera, Anderson lets the editor describe it in exacting detail drawn from Dahl’s prose. (“Six or seven times they went around, the small bulge chasing the larger one…”) It’s the viewer’s job to fill in the gaps between what’s being shown and what’s being described. It’s also the viewer’s job to reconcile the various influences at work in a film filled with theatrical flourishes via visible stagehands and stylized sets and a (literally) prosaic script that, were one to close one’s eyes, would work well as an audiobook or radio play. It’s both unmistakably Anderson and unlike anything the director has made before.

Anderson’s quartet of Dahl adaptations—which also includes “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” “The Swan,” and “Poison”—is the sort of form-bending project he’s been working toward for a while, almost since the start of a career that’s pushed the boundaries of what a film is supposed to be by imitating other forms. Starting with Rushmore, Anderson’s fondness for formal compositions, stage-like sets, and (a bit later) in-camera effects, suggested movies that had absorbed elements of live theater. The Royal Tenenbaums uses a book of the same name as its framing device. The Fantastic Mr. Fox, Anderson’s first Dahl adaptation, similarly opens with images of a book. The Grand Budapest Hotel nests a story within a novel, within scenes of a pilgrimage to its author’s grave. The French Dispatch brings to life an issue of a magazine. In retrospect, the Max Fischer Players’ theatrical adaptation of Serpico and its Vietnam War movie pastiche Heaven and Hell look like signs of what was to come, the first of many blurred lines between film and other sorts of art.

Anderson is a moviemaker above all, but his movies often suggest ambitious mixed media whatsits. In trying to explain Anderson’s latest feature to my daughter via text I wrote: “The movie is set up so you’re watching a 1950s TV special about the making of a play called Asteroid City. And then most of the movie is that play, but it doesn’t look like a play, it looks like a movie. (It makes more sense when you see it.)” I stand by that parenthetical. Anderson has a gift for getting audiences on his films’ wavelengths and taking them wherever he wants to go.

With these new Dahl adaptations, Anderson wants to get as deep into the pages of the author’s work as possible while remaining tethered to Wes Anderson country. Sometimes that means turning Dahl himself into an Anderson character. As drolly played by Fiennes, Dahl contributes to the narration of several of the shorts, most significantly “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar.” Addressing the camera from a recreation of Dahl’s famous writing hut, Dahl introduces the story of the eponymous ne’er-do-well (Benedict Cumberbatch). After Sugar begins narrating his own story, the film gives way to a tale found in a notebook in which Dev Patel plays an Indian doctor who meets Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley), a traveling performer who’s billed as “The Man Who Sees Without His Eyes.” In time, Khan takes over the narration to tell his origin story as he recounts the lessons of a great old yogi (Ayoade). If you’re keeping score, that's a story within a story within a story within a narrative framework.

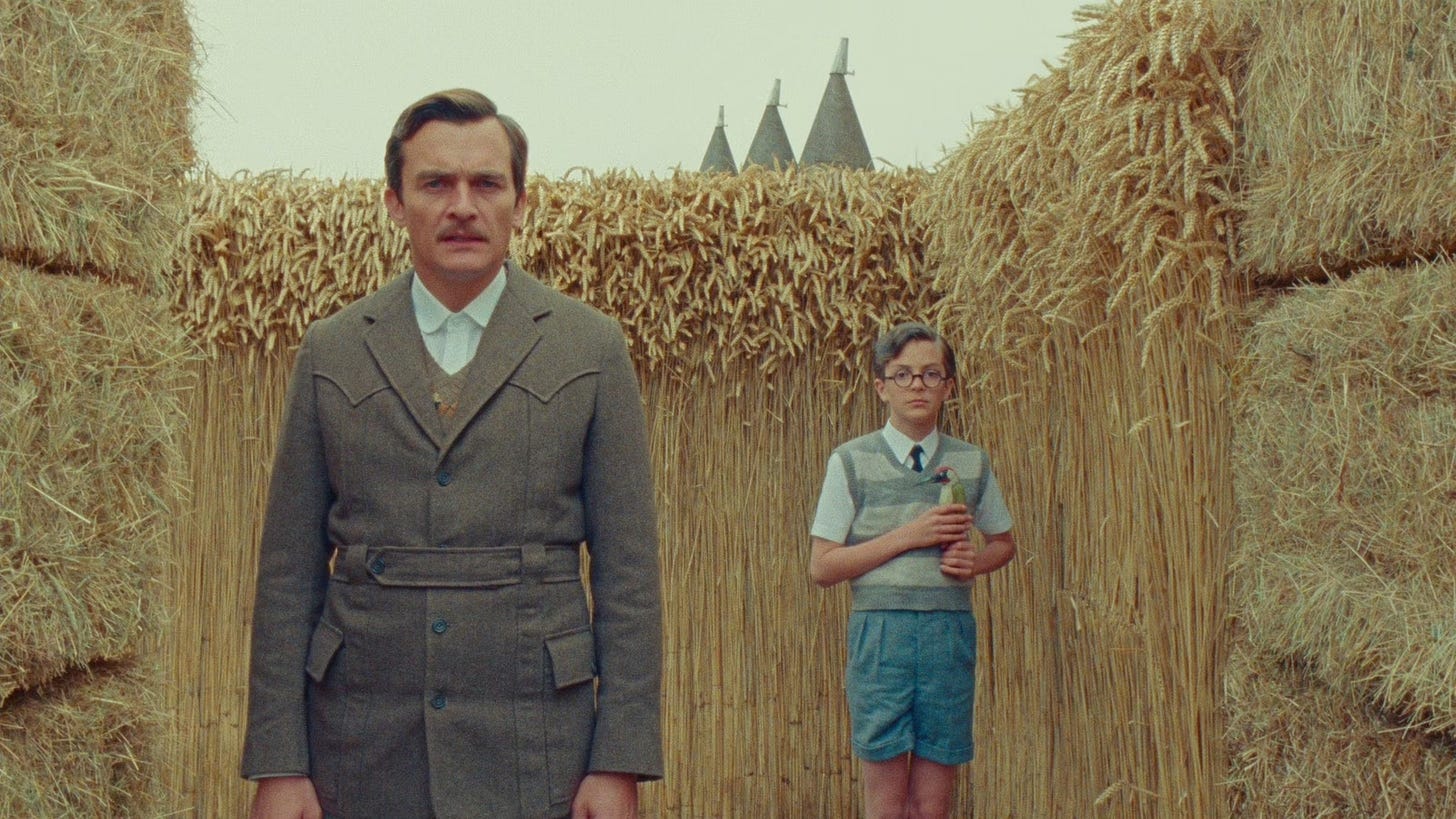

But it’s not the layer-cake structure that sets these shorts apart; it’s Anderson’s choice to film each as a story told directly to those watching, complete with unbroken eye contact between the teller and viewer. This intimate approach preserves Dahl’s voice while passing it between characters and allows Anderson to take a more experimental approach to visuals while still working within his established style. Much of the urgency of “Poison” comes from the breathless narration of Woods (Patel) as he attempts to prevent a man named Harry (Cumberbatch) from falling victim to the snake on his stomach. “The Swan” tells the story of a boy named Peter (Asa Jennings) and his near-fatal encounter with a pair of bullies. But, after a brief appearance, the bullies disappear from the film, leaving the adult Peter (Rupert Friend) to serve as narrator and perform his tormentors’ parts. These stories undoubtedly could be adapted in more conventional ways. What Anderson’s versions presuppose is… maybe they shouldn’t?

The months leading up to Asteroid City’s release saw the (probable) peak of a TikTok trend in which users filmed their everyday lives in Anderson’s style. The New York Times even offered a how-to piece for the curious that revealed just how easy it was to imitate Anderson, at least in the broad strokes. As cute as these videos are, there’s an almost AI quality to them. Their creators have studied Anderson well and get a lot right, but there’s no soul animating their work. And, as distinctive as Anderson’s filmmaking is, there’s a restlessness to it that’s easy to overlook. Anderson’s films may be instantly recognizable but, as the Dahl shorts confirm, he keeps finding new variations within that style, folding the unexpected within the predictable. Beneath the familiar trappings, his artistic evolution is hiding in plain sight.

I often think back to this Esquire feature from 2000 where they had a handful of film critics write essays on which up and coming director they thought would be "the next Scorsese." Then they had Scorsese himself make a pick and he selected Wes Anderson, who only had two films to his name at that point. I've often wondered what exactly he saw in him at the time but part of me thinks he may have recognized that kindred spirit of being an artist who, as you mention Keith, "keeps finding new variations within that style." That endless curiosity and desire to keep pushing seems to be what unites the greats, moreso than similar themes or visual styles.

TL;DR Shockingly, Martin Scorsese has a keen eye for talent.

I've been a little blown away by how great I thought these were. My favorite is "The Swan." I like it when Anderson lets a little anger into his work -- it's why I love "Isle of Dogs" so much -- and that one has a lot of it. Also, I didn't know Rupert Friend was that good! He's *terrific* in that.