Under the Sycamore Trees: The Night ‘Twin Peaks’ Went Off the Air

With the finale to the original run, David Lynch patched together pieces of a broken series and set the stage for the rest of his career.

After Twin Peaks debuted its two-hour pilot episode on April 8, 1990, the show became a sensation, one instantly hailed as a turning point for what was possible on television. By the time it aired its final two episodes on June 10, 1991, it had turned into a punchline. Ratings plummeted throughout the second season, a decline unstopped by the revelation of Laura Palmer’s killer, the central mystery around which the series revolved. ABC moved Twin Peaks around the schedule before pulling it entirely in February with six episodes still unaired. Four debuted in March before the network yanked it again. The long-overdue premiere of Twin Peaks’ final two episodes on the sleepy Monday night of June 10th was the definition of a non-event that inspired weary postmortems wondering what had gone wrong.

“I stopped writing about Twin Peaks because, frankly, I was embarrassed by it,” critic Marvin Kitman wrote in Newsday. “I had given up on it. Several times. I have given up on Twin Peaks the last two years more times than I stopped smoking or eating ice cream.” For Kitman, the blame lay with David Lynch, who co-created the series with Mark Frost but whose involvement had waxed and waned throughout its existence. “He had us in his hands,” Kitman continued. “We were ready to accept anything after that first season. He was 13 runs ahead in the eighth inning and blew the lead. He squandered it with all that mumbo jumbo. Bob possessed him, to put it most kindly.”

That Kitman wrote his column without watching Twin Peaks’ final two episodes might partly explain the sentiment, but even those who tuned in treated them wearily. “It was two episodes strung together to recoup cents on the dollar of a bad investment,” wrote Tom Jicha in the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel. It was as if when the revolution Twin Peaks promised failed to arrive, some felt the need to confirm their loyalty to the old regime. The numbers at least bore out the wisdom of this position. Twin Peaks’ final episodes finished 59th in that week’s Nielsen’s rating, tying the Fox TV movie The Sitter but landing below another ABC program: Morris the Cat Salutes Hollywood Pets, hosted by Alex Trebek. (It at least trounced NBC’s C. Everett Koop Special.)

Somehow no one seemed to notice that Lynch, who directed the finale, ended Twin Peaks even more radically than he began it. Twin Peaks was broken and soon to be thrown away. Lynch decided to patch it back together again, using the pieces to transform the series into an even darker, deeper, dreamier, and more haunting version of what it had once been. It’s a lesson he’d file away for later use.

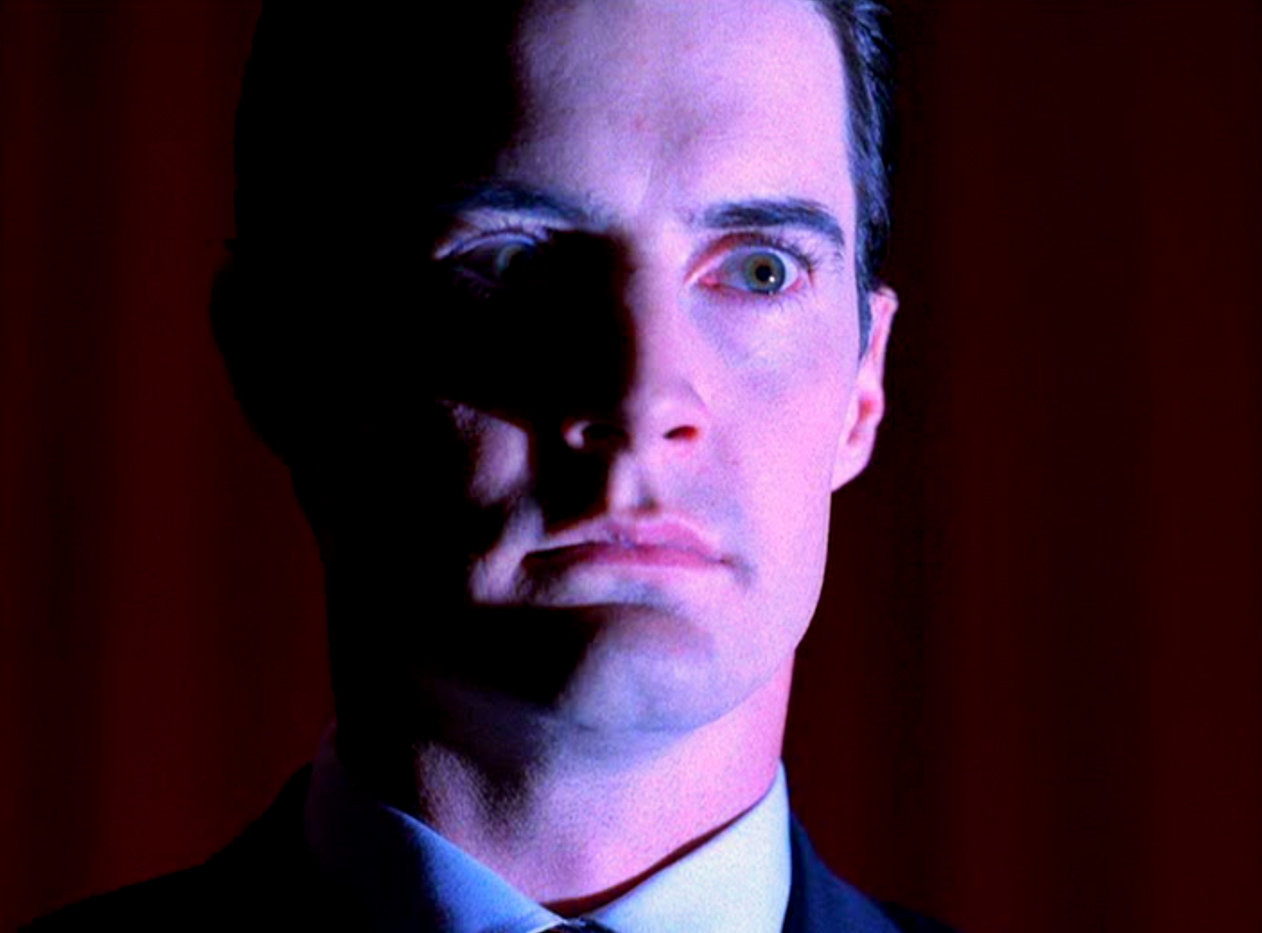

If you tuned in that night, you wouldn’t see that coming from the penultimate episode, “Miss Twin Peaks.” Directed by Tim Hunter, the season’s 21st episode continues to advance a number of second-season subplots. These include the eponymous beauty pageant, some business about UFOs, some other business about saving the pine weasels and the true parentage of Donna (the late Laura Palmer’s best friend, played by Lara Flynn Boyle), and some extremely silly business in which the disturbed, eyepatch-wearing Nadine (Wendy Robie) continues to believe herself to be a teenager. As with much of the season’s homestretch, the action is driven by the schemes of Windom Earle (Kenneth Welch). A onetime partner of protagonist Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan), Earle moved onto a second career as an insane criminal mastermind some time after killing his wife Caroline, with whom Cooper was having an affair.

Earle had traveled to Twin Peaks both to exact revenge on Cooper and to find his way to the Black Lodge, the supernatural space just beyond reality that’s home to the mythical forces of good and evil central to the series. But, as with much of Twin Peaks (and Lynch’s work in general), the Black Lodge doesn’t easily lend itself to description. Or, maybe more accurately, any attempt to explain its mechanics takes the poetry out of what Lynch does with it. We see only a few aspects of the Black Lodge in Twin Peaks’ ABC episodes (and only a bit more in subsequent incarnations), almost all of them contained within what would become known as the Waiting Room, which Cooper had previously visited in dreams: a tiled floor with a jagged black-and-white pattern, some worse-for-wear thrift store furniture, some floor lamps, a budget reproduction of the Venus de Milo, and, most famously, red curtains that stretch from the floor to the never-seen ceiling. They’re all the building blocks the series needed to create images that never quite tip into nightmare. Until, here, they do.

For those hoping for closure, Twin Peaks’ finale—written by Frost with Harley Peyton and Robert Engels, writers who’d been involved with the show since it was picked up to series—was frustrating on two fronts. In form, Twin Peaks was a nighttime soap opera in the vein of Dynasty and Dallas. As with its inaugural season, Twin Peaks’ second season ends, true to its inspirations, in a pile-up of cliffhangers and unanswered questions. These include a bomb in a safe-deposit box that seemingly takes out several characters, Audrey (Sherilyn Fenn) and Pete (Jack Nance) among them; the question of who fathered the pregnant Lucy’s (Kimmy Robertson) unborn child; and the fate of Ben Horne (Richard Beymer), who’s injured in a tussle with Dr. Hayward (Will Frost), the man Donna previously assumed to be her father. Anyone seeking resolution, and perhaps not understanding how television works, would wonder why the creators of a doomed show wouldn’t take the opportunity to tie up loose ends.*

This was me as an 18-year-old Twin Peaks fan, the beginning of a long tradition of not liking David Lynch projects I’d later regard as extraordinary, if not outright masterpieces.** But, like others, I was even more unsettled by the Black Lodge scenes. First explicitly referenced in the dark heart of Twin Peaks second season—the rocky, post-Laura’s-killer-reveal stretch—the Black Lodge was reportedly originally planned to resemble a dark version of Twin Peaks’ Great Northern Hotel before Lynch remade it as a place in which all exits lead to the Red Room, or some room that only looks like the Red Room. It’s a place of spirits and doppelgängers and beings that are and aren’t what they seem.

Lynch’s presence behind the camera can be felt from the first moments of the finale, which plays out as a long, cuddly two-shot of Kimmy and her sometime beau Deputy Andy Brennan (Harry Goaz). It’s evident elsewhere, too, like the patient way the camera follows an elderly bank clerk as he shuffles from the vault to the drinking fountain and back again, then kind of wanders aimlessly, unsure of what to do. These play like Lynch bringing his style to words largely given to him by others. The by-all-reports heavily improvised Black Lodge scenes play like unadulterated Lynch, the work of a director with an unmatched talent for aligning the language of film with the language of dreams.

After following Earle to Glastonbury Grove, an isolated wooded spot surrounded by sycamore trees, Cooper tells Sheriff Harry S. Truman (Michael Ontkean), “Harry, I have to go on alone.” Asked why, Cooper provides no answer, but these will be the last words Cooper—the real Cooper, not the evil duplicate who will emerge at episode’s end asking “How’s Annie?”—says to Truman, his closest friend since his arrival in town. From the start, Cooper had been portrayed as a man with an intuitive understanding of how the universe works, so these words deserve some special attention. There are some points from which everyone must proceed alone.

After Cooper walks around a white circle at the center of the grove, the backdrop becomes a large red curtain. Cooper walks through the curtain and into another world where lights strobe, the Man from Another Place (Michael J. Anderson), a figure he’s met in the Waiting Room before dances as singer Jimmy Scott sings of promising to see someone under the sycamore tree before fading away. Like Cooper, we’ve passed into a place where the rules governing reality no longer apply.

In the scenes that follow, Cooper is given cryptic clues by the living (the aged waiter from the second-season premiere (cowboy actor Hank Worden), the dead (Laura), and the otherworldly (The Man from the Other Place, the Giant (Carel Struycken). Some of those he meets seem helpful, others threatening. All speak in the strange backwards-turned-forward pattern. Then the screaming starts, and as Cooper wanders back and forth between seemingly identical rooms, his experience becomes increasingly troubling as it builds to an encounter with Earle and Bob (Frank Silva), the locus of evil in the Twin Peaks world, that produces the Cooper doppelgänger soon to take his place in the world, leaving Cooper in the Black Lodge, where he’ll remain until the series’ revival in 2017.

These are some of the strangest, most disturbing scenes ever aired on network television, breaking the record previously held by… let me check… right… Twin Peaks. It’s the work of a creator taking advantage of every creative freedom afforded him within the limitations he faced. In Twin Peaks’ last moments as a network television show, Lynch used a spare set to suggest an infinite space and an unknowable dimension. Mid-decade he’d make Lost Highway, in which one reality seems to overwrite another, at least for a little while, an approach he’d revisit with Inland Empire. In 2001, Lynch would unveil another project largely salvaged from the wreck of a venture into television, Mulholland Drive. Twin Peaks: The Return often resembles the second-season finale writ large. Though made with affection and care for the previous series, it’s a magnum opus that plays like Lynch knew he could explore whatever he wanted as long as it fell broadly within the confines of the Twin Peaks universe. The result is an 18-episode summing up of all things Lynch, drawing on everything from his first experimental films to the semi-home movie aesthetic of Inland Empire to, oh yeah, Twin Peaks.

What do these otherworldly season-two finale scenes mean? There are many wikis and YouTube videos out there that attempt to place everything into a coherent metaphysical system, Lils aplenty doing intrepetive dances as they attempt to share the code that reveals all. And that’s fine. But I think we can all agree that, to borrow a line from the work of another filmmaker, it all has something to do with death. Lynch’s works often did, particularly in their final scenes, from the peaceful passing of John Merrick in The Elephant Man to whatever fates greet the protagonists of Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive to the reunited brothers looking at the stars in the final moments of The Straight Story to the death that’s not a death of Inland Empire. Left by the series to drift amongst the ghosts, Cooper never really comes back from the Black Lodge, even in Twin Peaks: The Return, at least not in a form that allows him to stay long where he wants to be, in a world he’s helped make safe from harm, purged at last of the Black Lodge and its corruption.

Yet, in interviews at least, Lynch didn’t talk about death as an enveloping darkness. Asked by the BBC in 2023 why he continued to speak of longtime collaborator Angelo Badalamenti, who’d died the previous year, in the present tense, Lynch (an enthusiastic follower of Transcendental Meditation), replied, “I believe life is a continuum, and that no one really dies, they just drop their physical body and we'll all meet again, like the song says. It's sad but it's not devastating if you think like that. Otherwise I don't see how anybody could ever, once they see someone die, that they'd just disappear forever and that's what we're all bound to do. I'm sorry but it just doesn't make any sense, it's a continuum, and we're all going to be fine at the end of the story.”

Lynch’s death last week came as a shock, even though he shared that he suffered from emphysema, whichmade it difficult for him even to move across the room the previous fall. It is a tremendous loss, because of the work Lynch created but also the spirit with which he worked and lived while he was with us. Maybe it helps to think of it this way: He had to go on alone.

* Years later, Twin Peaks: The Return answered some of these questions comically (Lucy’s child) and others tragically (Audrey’s fate) while consigning others still, like Donna’s parentage, to the land of How Much Do You Really Care?

** See also Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Lost Highway, and Inland Empire. Actually, that tradition probably dates back to me, aged 11, walking out of Dune because I was confused and frustrated, but I think I get a pass on that one.

Going to share my own Twin Peaks experiences here. For most of high school and onwards, I kind of hated Lynch, and his world, and the more people liked it, especially Twin Peaks, the colder it left me, the whole, get this, she's the prom queen, but also an underage prostitute thing. I didn't feel like the projects really gained by all the withholding and obscuring that they did, and that there was a kind of cheapness and forced character to the surrealism. Plus all kinds of (to me) awful stylistic missteps, like the presence of Marilyn Manson in Lost Highway.

I think the year after The Return I watched all of Twin Peaks with my girlfriend, and then The Return, and I don't know, man, it really did something to me, and it really captured something I was feeling. There was something so overwhelmingly desolate about it, the characters seemed so hopelessly overmatched, so many miles and years away from what they needed to do and be, all of which weirdly turned it into a work of realism, about the desolation and hopelessness of our world. I think The Return and The Sopranos are the only two shows that really capture what it's like to live in American, minute by minute, day by day, just wandering through this purgatory stretching out miles and miles in every direction, waiting for grace--like Beckett's End Game. The settings are so sharp, the corporate stuff, the developments, the way he downgrades Twin Peaks to a pill-swamped hell hole, there's the awful freakishness on the one hand, but on the other hand, everything is so crisp and sharp. (Lynch and Mann maybe the only two directors who successfully made the jump to digital?) There's lots of stuff in The Return that doesn't exactly work, or contribute, or that's just there for effect, rather than thematic resonance. And I kind of hate Lynch the character, too. But I love The Return for scrubbing all the shiny happy stuff out of the original series and just leaving this awful, terrible void, with all the characters left, and even Cooper, tottering at the precipice, trying to hang on.

Audrey's fate is still maybe the most upsetting thing in the finale, partly because it's profoundly sad but also basically a minor subplot. (She was also possibly the character most ill-served by season 2? But I haven't seen it since 2017 so maybe I'm wrong about that.)

(OK yes some of this just stems from my massive crush on Audrey/Sherilyn Fenn back in 1990.)