'Tin Cup': The Zen of Never Laying Up

In Ron Shelton's sports movies, failure is the road to enlightenment.

The 1999 Open at Carnoustie. Final day. 18th hole. A Frenchman named Jean Van de Velde was carrying a three-shot lead over the nearest contender, and needed only a double-bogey to win the tournament. For a professional golfer with that big a lead, the final hole is usually ceremonial, a chance to soak in the approbation of the gallery as he strolls his way to victory against the majestic backdrop of a Major course around magic hour. Yet at the tee shot on the Par 4, when he might have gone conservative and hit a clean iron down the fairway, Van de Velde instead reached for a driver. On the broadcast, there was immediate alarm over this choice—“He’s going to be at least three shots ahead. A six will do.”—and, sure enough, off the shot went to the right. Not an ideal start, but not a disaster if he were to lay up, avoid the water hazard in front of him, and not try to go for the green. Smack. The ball hit the grandstand and ricocheted into “the hay,” which is basically the rough, but with tall grass above the waistline.

For his third shot, Van de Velde would have to go over “the burn,” the Scottish term for “creek” or “river,” in order to find the green behind it and a couple of sand traps. Shooop. That’s the terrible sound Van de Velde’s club made as it swept through the hay, diminishing the club’s power to such a dramatic extent that the ball plopped ineffectually into the burn. And then came one of the great moments in sporting meltdowns, as anticipated via an instant classic of on-air commentary: “He’s surely not going to go and climb down and wack it out of there, no. That would be totally ridiculous. What are you doing? What on earth are you doing?” Van de Velde took off his shoes, rolled up his pants and contemplated hitting out of the water rather than taking a penalty stroke. He eventually wised up, but the comedy of errors continued, and he backed his way into a three-person playoff that he lost. The winner: Paul Lawrie.

Paul Lawrie only won that one Major, and though he’d have a decade-long career, he’s barely the answer to a trivia question. But even casual sports fans will never forget Van de Velde’s odyssey on the 18th, as a combination of nerves and poor decision-making led a golfer to take off his shoes and socks and start his descent into the water, where his ball laid tantalizingly on the surface, tempting either a catastrophic mistake or a moment of unprecedented triumph. He ultimately, at long last, opted to play it safe and give himself a chance to win, even though his confidence was too shaken for him to salvage the double-bogey and take home the Claret Jug. He would never come that close again.

The story of Jean Van de Velde so closely mirrors Ron Shelton’s Tin Cup that it sounds like a case of art imitating life, but in fact it was life imitating art, because the film had been released three years earlier. Like Van de Velde, Shelton’s hero, Roy “Tin Cup” McAvoy (Kevin Costner), has to make the Open championship the hard way—not through success on the professional tour, but through the qualifying events that can give obscure pros the opportunity to compete at the highest level. Like Van de Velde, Roy heads into the final hole with a chance to win outright or fall into a possible three-way playoff with two other contenders, including his slick rival, David Simms (Don Johnson). And like Van de Velde, Roy should make the safe play by choosing an iron instead of a wood, but baffles the conservative commentariat by gambling on greatness.

It ends worse for Roy. It also ends much, much better.

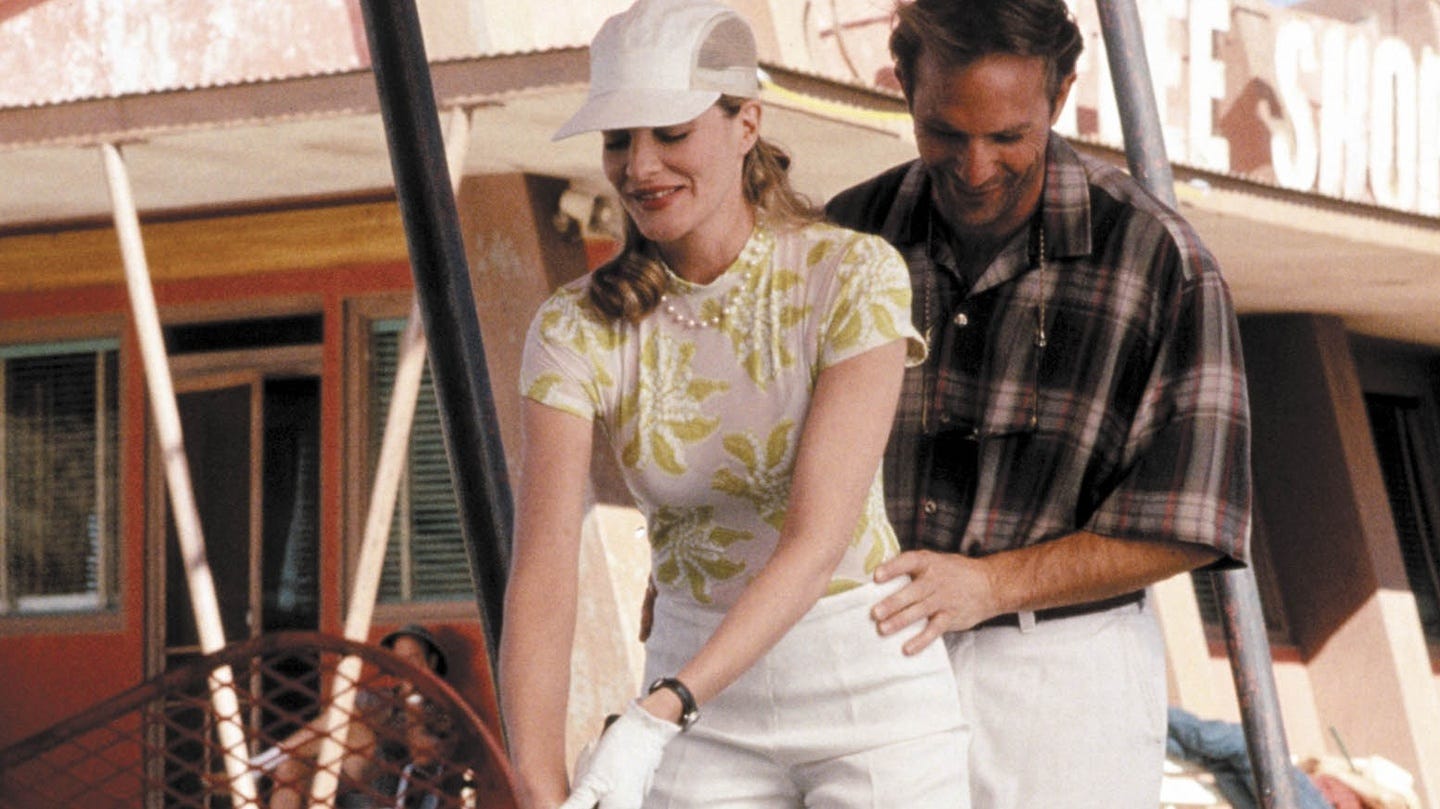

In retrospect, perhaps Van de Velde’s biggest mistake on that day was backing off his insane notion to hit it out of the water. Because given the same situation, Roy McAvoy would have stripped to his boxers and sweat-stained undershirt and taken the plunge. Nobody could have stopped him, either—not his best friend and caddy Romeo (Cheech Marin), who snapped the woods in his bag to halt an earlier meltdown (Roy then snapped all the irons, save for the seven), and not his love interest Molly (Rene Russo), who has tried to use her experience as a therapist to break his self-destructive habits, but has given up trying to change him. Temperamentally allergic to the Big Game ending, Shelton allows Roy to strike one miraculous, transcendent golf shot, but only after he’s thoroughly humiliated himself on national television. Van de Velde was not so lucky.

In a rousing conclusion to his unofficial sports trilogy, following the greatest baseball movie ever made (1988’s Bull Durham) and the greatest basketball movie ever made (1992’s White Men Can’t Jump), Shelton used Tin Cup, the greatest golf movie ever made, to philosophize profoundly and hilariously about what sports really mean. And that involves redefining wins and losses, defying all the clichés we lap up so readily from films and other broadcast narratives, and thinking about the holistic value of games that are not always going to be there, even for those rare and fortunate few who call themselves champions. Whose life do you want more: Kevin Costner’s in Bull Durham and Tin Cup? Or the lonely trajectories of GOATs like Tiger Woods or Michael Jordan?

Here is the thesis of a Shelton sports movie, laid out beautifully by Rosie Perez in White Men Can’t Jump:

Sometimes when you win, you really lose. And sometimes when you lose, you really win. And sometimes when you win or lose, you actually tie. And sometimes when you tie, you actually win or lose. Winning and losing is all one big organic globule from which one extracts what one needs.

For the most part, Roy has only known losing, though even by his exceedingly modest terms, he’s closer to happiness than it appears. Once a talented college golfer, Roy long since tumbled to the role of golf “pro” on a dusty driving range outside the West Texas town of Salome. He drinks too much, deals in cash to steer clear of the IRS, and likes to gamble with Romeo and his buddies on stupid things like which bug will hit the porch zapper first. But as played by Costner at his most appealingly laid-back, Roy isn’t as far from happiness as his range is from the nearest PGA golf course. When Molly turns up for lessons in a chic form-fitting skirt, bearing $200 worth of swing-enhancing equipment from the Golf Channel, Roy is instantly smitten. That desire is uncomplicated and straightforward—a “grip it and rip it” situation, to put it in his golfing parlance.

The complicated part is making himself worthy of her, and perhaps holding himself to a slightly higher standard. Molly has trouble understanding golf as intuitively as he does, but as a mental health professional, she has the correct read on him instantly. Roy tells her as a first lesson that golf is “about inner demons, self-doubt, human frailty and overcoming all that crap,” and most people who have ever played the sport know that he’s right about how aggravating it can be. (My brother-in-law once told me, “I’ve never spent so much money being bad at something.”) But when he suggests to Molly that perhaps he’s “chock full of inner demons,” too, she sees right through it. “Nah,” she says. “You’re chock full of bullshit.”

It turns out, of course, that Molly happens to be seeing David Simms, his former college teammate, who is his opposite—wildly successful, yes, but the type of golfer commenters praise as “smart” for never taking chances and a smug jerk behind the scenes. In an act of fake magnanimity, David hires Roy to be his caddy on a course Roy knows exceptionally well, but it doesn’t take long for Roy’s ego to blow up that opportunity for easy money.

One aspect of sports culture that Shelton emphasizes here and in White Men Can’t Jump especially is the competitive relentlessness of men who need to show each other up. Woody Harrelson may play a hustler in White Men Can’t Jump, but he’s enough of a sucker to gamble all his winnings to his partner to prove he can dunk—something he’s never done before. Throwing wagers behind clubhouse side bets is a Shelton thing to do. Roy feels more comfortable winning a $400 hole with garden tools for clubs than he does going after a purse in the buttoned-down world of professional golf.

Shelton was himself a minor-league infielder before channeling those experiences into Bull Durham, and he has a keen sense of where never-was athletes can find happiness when they fall short of their Big Game dreams. One of the best touches in Bull Durham is when Costner’s character breaks the career home run record for the minor leagues, a milestone celebrated by his girlfriend (Susan Sarandon), but really more a monument to the fact that he was never cut out for The Show. His job was to nurture more talented people—obnoxious, undeserving people, with 100-mph fastballs and moldy shower shoes—to play in the cathedrals he’s doomed to worship from afar. The film is about his realization that the consolation prize, a quiet retirement with the minor-league groupie he loves, is better than sporting immortality. Forget the Big Game. He doesn’t even finish out the season.

Of all the Shelton heroes, Roy is the only one who’s held back entirely by his self-destructive tendencies. He has the talent for professional greatness, but not the discipline. Yet he’s the closest to true enlightenment, because there’s never a sense that he needs to win the Open or make the PGA tour in order to find happiness. His quest on the course is more Zen, a lifelong pursuit of that unattainable perfect shot, which is why he can’t bring himself to lay up on the final hole— or even take a drop from a shorter distance. That’s not a meltdown of the Van de Velde variety, but a chance to realize his own idiosyncratic quest on the grandest stage. Even though Molly is supposed to be helping Roy to avoid such mental lapses, she realizes in this moment that he’s playing a different game—impractical, perhaps lunkheaded, but unruly and beautiful, too. She can’t suppress a cackle of approval.

Roy sinking “the greatest 12 of all time” is the most crowd-pleasing moment in a Ron Shelton film, and we come to embrace it, just like Molly does, because Shelton has redefined what winning is all about. For a sports culture where championships are everything, it’s a radical notion to understand Roy, a classic head case, as a winner. Roy is happiest holding court at a Waffle House with Romeo and his coterie of friends from West Texas, and there’s no need for fame and fortune to make it possible, only a desire to share it with someone he loves. He’s extracted what he needs from the “big organic globule” of winning and losing, and achieved a beer-swiller’s enlightenment.

Excellent piece, with one correction: the greatest baseball movie is the original "Bad News Bears."

God, I love Tin Cup, and I love this appreciation of it. Time to watch it once again and remember what winning means.