The Vanishing of 'The Vanishing'

With 'Speak No Evil' in theaters this week, it's a good time to look back on the strange case of a European director who Americanized his own horror masterpiece.

“Does it have to be an old mill?”

In one of the best jokes in David Mamet’s moviemaking satire State and Main, a small production is scrambling to find its footing in a small New England town after its leading man’s predilection for underage girls got them kicked out of their original location. There are alterations big and small to consider for the overwhelmed first-time screenwriter, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, but this is particularly onerous compromise for him. Because, you see, the title of his movie is The Old Mill. (The images and clips are removed, but Mike D’Angelo breaks down this brilliant gag well in his old A.V. Club column Scenic Routes.)

The question probably wasn’t asked of the Dutch director George Sluizer so directly, but it was something he had to consider when his 1988 thriller The Vanishing (originally titled Spoorloos, meaning “without trace”) was being remade in Hollywood in 1993: “Does it have to have that ending?” Were American audiences ready for what would become, almost instantly, one the most famously chilling endings in movie history? Could you, one year after Bruce Willis rescues Julia Roberts from the death chamber in the movie-within-a-movie in the Hollywood send-up The Player, get away with tacking on a similar 11th-hour rah-rah moment? The Vanishing would not be the first European arthouse favorite to get mangled up for American audiences, but it’s the rare example of the original director himself doing the mangling. Who slashes his own canvas?

There have been other European filmmakers who have Americanized their own work in the past, like Francis Veber, whose run of silly French comedies started with him turning Les Fugitifs into Three Fugitives with Martin Short and Nick Nolte, and Michael Haneke, whose English-language Funny Games, with Naomi Watts, seemed intended to scold Americans directly for the violence and sadism they pass off as entertainment. But neither of those films differ significantly from their predecessors. The Danish director Ole Bornedal, working with Steven Soderbergh, made some changes to his 1994 thriller Nightwatch for a version with Ewan McGregor and Patricia Arquette, but the Weinsteins, who bankrolled the film for Miramax/Dimension, turned the post-production process into one of their patented boondoggles. After reshoots and a new ending, Bornedal distanced himself from the theatrical cut.

The Vanishing is a more peculiar case, because Sluizer did not have the ending forced on him. He also waved off comparisons to his countryman Paul Verhoeven, who’d been able to make the transition from Holland to Hollywood with films like Robocop and Basic Instinct. Sluizer was 60-years-old, a veteran of documentary and feature filmmaking for over three decades, and he told The New York Times, “I’m a little too old to feel that making a Hollywood picture is going to build my career.” For him, the motivation was “to recreate characters in a different culture, in a different movie with different actors, but based on the same story.” In that same Times piece, which is loaded with juicy quotes, screenwriter/co-producer Todd Graff suggests that Sluizer had a tough time adjusting to the pace and conditions of studio filmmaking, likening him to Alice in Wonderland. For his part, Sluizer, a man accustomed to being “captain of the ship,” seemed to have multiple hands yanking the wheel.

None of the quotes from Sluizer are as downright craven as the one co-producer Paul Schiff, who says, “We acknowledged and embraced the expectations that we know exist in an American audience for this kind of movie, which are that the character whom we grow to identify with do triumph in some significant way, that there’s a positive, affirming result at the end of the journey.” (That “positive, affirming result”: The bad guy getting a shovel jammed through his mouth.) But Sluizer’s assumptions about American audiences are condescending to the extreme.

To wit:

“It’s the difference between being more intellectual or more gut level,” Mr. Sluizer says. “I know if you do a mainstream American movie, you have to maintain a faster pace. If you sit in a movie theater in northern Europe, you will never hear an audience make noises reacting to a picture. Here, they scream and gasp. They applaud. The audience participates in a way that is more childlike.”

Seen back to back, Spoorloos (which I’ll call the Dutch version to avoid confusion) and The Vanishing are a fascinating study in exactly what Sluizer is talking about, to the point where the American version seems like an experiment in commercial filmmaking, however cynical it may be. There are echoes of the original in the remake, where individual shots and plot points are more or less replicated, but the departures are illuminating quite apart from the ending, from Sluizer’s new points of emphasis, his additional cuts, and his oft-curious notions of how Americans behave.

Before getting into my observations about these two films—which, naturally, will get into heavy spoiler territory—here’s the premise, which is common to both. Character/actor names are listed with the 1988 film first and the 1993 film second:

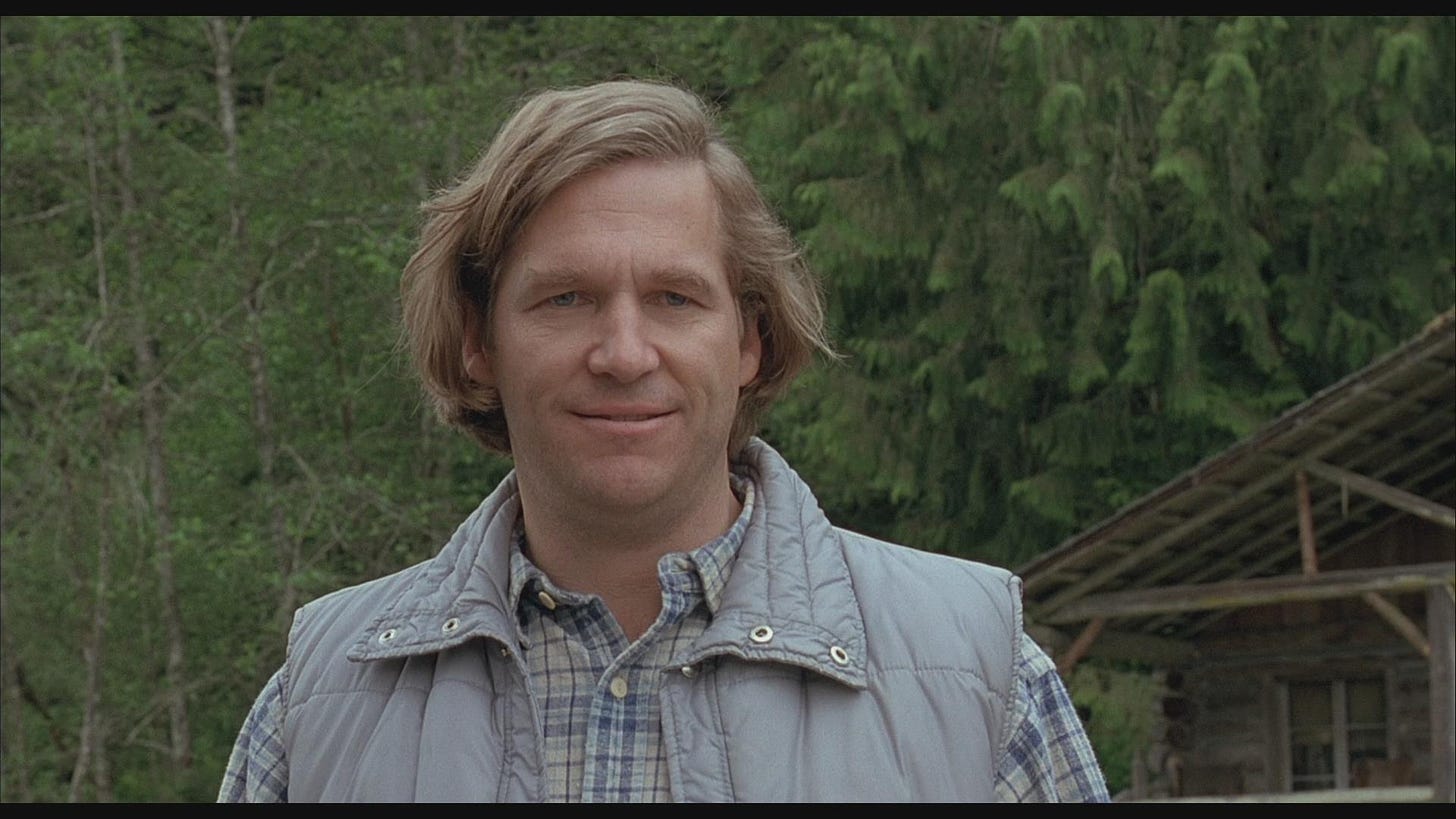

After running out of gas in the middle of a highly symbolic tunnel, a couple on vacation fuel up at a crowded station. While Saskia/Diane (Johanna her Steege/Sandra Bullock) ducks into the convenience store for coffee, her boyfriend Rex/Jeff (Gene Bervoets/Kiefer Sutherland) waits by the car. And waits. And waits. Three years later, Rex/Jeff still obsesses about his missing girlfriend, regularly posting signs related to her disappearance. Meanwhile, we learn a lot about the woman’s abductor Raymond/Barney (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu/Jeff Bridges), a seemingly ordinary family man who’s carried out the crime with meticulousness and sociopathic purpose. Though Rex/Jeff has since entered a fraught relationship with a new woman, Lieneke/Rita (Gwen Eckhaus/Nancy Travis), his persistence draws Raymond/Barney’s attention and gives him the opportunity to discover the truth of what happened… under a frightening set of conditions.

Here are six observations about Spoorloos and The Vanishing:

“Does it have to be a golden egg?”

Both films are based on a 1984 novella by Tim Krabbé called The Golden Egg. (Fun fact: Krabbé’s brother is ace character actor Jeroen Krabbé, who made his own journey to America after appearing in Verhoeven films like Soldier of Orange and The Fourth Man.) At the beginning of Spoorloos, Saskia recalls a recurring dream she has about drifting through outer space in a golden egg and subsequent dream about a second egg containing another person, and a fear she holds about the eggs colliding. Rex has a similar dream years later. There’s a prescience to Saskia’s dream—the eggs do collide, to devastating effect—but the egg itself could represent a lot of different things, with safety and peace on one end and isolation and suffocation on the other. Whatever the case, the story establishes a bond between Rex and Saskia that doesn’t end with her disappearance and accounts for the continued urgency he feels about finding her.

Graff jettisoned what he called the “heavy symbolism” of the egg, which is a reasonably defensible choice, albeit a “Does it have to be an old mill?” gesture that typifies his willfully dumbed-down script. The golden egg dream is the sort of abstract, psychic connection that you might see in European films but not in Hollywood. At the same time, the scene at the beginning of both films in the tunnel, when the car stalls out and Rex/Jeff leaves Saskia/Diane to get fuel, does set up a later promise that he’ll never leave her alone again like that. Though The Vanishing loses the golden egg conceit, Graff is probably correct in thinking that promise is enough to justify Jeff’s obsession with finding her.

“I’m a hero. But don’t trust the hero.”

One of the unusual and distinctive aspects of Spoorloos is how much time Sluizer spends with the antagonist, when a more typical thriller would focus more on the hunt to track him down. It’s no accident that Rex and Raymond both have names that start with the letter “R”: Their stories are told in parallel, with roughly equal attention given to both and a disturbing kind of symbiosis that occurs once they finally get together. But what stands out about the film’s treatment of Raymond is how much it uses flashbacks as inflection points in his life that account for his sociopathic behavior. When Rex and Raymond are in the car together, driving toward the area where Rex will find out what happened to Saskia, Raymond explains, with remarkable self-awareness, the impulses that led to this horrific act. As a teenager, he consciously jumped off a balcony, breaking his leg and cracking ribs, because he wanted to act “against what is predestined,” despite the consequences. As an adult, he impresses his children by leaping off a bridge into a river to save a little girl from drowning. Yet it was at this moment, he explains, that he conceived doing “the most evil thing” as a counter to his heroism.

The Vanishing deals only in half-measures with Barney, because it’s too scared of slowing down the pace and confronting the audience with abstraction. We see a lot of Barney rehearsing his abduction scheme in both films, but the philosophical underpinnings of the kidnapping and the horrors that follow are given short shrift in The Vanishing. He’s not as intellectual and even his double life as a family man has been drastically reduced, with only one child as opposed to three. That reduces him to more of a generic creep rather than a self-aware sociopath who’s able to pass as normal as if he’s expertly playing a role. (Can you ever feel comfortable around a guy who mumble-sings Barry Manilow’s “Copacabana” to himself?)

You want coffee? Here’s a glass of milk.

Perhaps the biggest change from Spoorloos to The Vanishing besides the ending is the girlfriend who enters the picture three years after the abduction. In Spoorloos, Lieneke is a kind and understanding woman who represents an appealing off-ramp for Rex if he can let Saskia go, but who ultimately leaves once it’s obvious that his obsession with Saskia’s fate takes up far more real estate in his head than she does. In The Vanishing, however, Graff writes Rita as a “strong” American woman who imposes herself on Jeff from the moment she sees him and never lets him go, even when she discovers that he’s been posing as a weekend warrior in order to work on the case in a seedy motel room. In what has to be one of the bigger meet-weirds in movie history, an exhausted Jeff sits down at the diner Rita is waitressing and asks her for a cup of coffee. Noting that he looks bleary-eyed, she not only refuses to serve it to him but insists that he have a big glass of milk instead. Then when he’s finished with the milk, she refuses to let him drive home and insists that he sleep on a cot in the back of the diner.

This unprecedented diner-waitress behavior establishes Rita as a person who has decided that Jeff is her guy and refuses to let him push her away. He’s going to take that big glass of milk from her if she has to dig him out of a coffin to do it. For the American version, Graff and Sluizer need to engineer a new, “happy” ending to reverse the irony and despair that ends Spoorloos and so Rita becomes the answer, a third party who can disrupt the deadly bargain these two men strike with each other. It’s a dramatic miscalculation, though it does lead to the funniest Vertigo homage imaginable, when Rita turns up at Jeff’s secret motel room in a wig to suggest his missing ex.

“Who’s Jeff Harriman if he’s not the guy looking for Diane?”

To credit The Vanishing, the bulked-up role for Jeff’s new girlfriend underlines an important point: That he loves Rita more than he loved Diane, but his need to know the truth about what happened to her is more important than love. This is what brings Rex/Jeff and Raymond/Barney together in both films, a fateful intersection of complementary obsessions. Raymond/Barney has an odd respect for the lengths Rex/Jeff continues to go, three years after the fact, to find out the truth, which turns borderline pathological when he opts to “experience what she experienced.” In The Vanishing, Jeff is much more explicit in telling Rita that Diane as a person doesn’t mean as much to him as she does now, but his curiosity is too overwhelming for him to love him the way she wants and deserves. Spoorloos is the subtler film, so it settles for implying Jeff’s feelings for his new girlfriend rather than spelling them out but at least The Vanishing is trying to raise the emotional stakes a bit.

“I hope you like roast beef.”

Jeff Bridges is my favorite living actor. The Last Picture Show, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Fat City, Fearless, The Big Lebowski, Cutter’s Way, Tucker: The Man and his Dream—the list of great performances and great movies goes on and on. But what in the world is he doing in this movie? His Barney affects a marble-mouthed, unplaceable European accent that makes him seem so much like an alien that Leigh Singer of Little White Lies compares it aptly to his work in Starman. This leads to some delectably weird moments, like him offering Jeff two roast beef sandwiches he’s tucked away in the glove compartment, but he’s credible neither as an academic nor a family man. He’s immediately recognizable as the type of guy you’d cross the road to avoid.

“We don’t drink that anymore.”

The end of Spoorloos is astoundingly shocking yet totally inevitable. Raymond correctly gambles that Rex’s curiosity will override his fury over what Raymond has done, so he’s able to convince Rex that he will find out the truth if he’s willing to go through exactly what she went through. So he takes a swig of drugged coffee—his girlfriend was drugged with chloroform in a hankie—at the gas station and allows Raymond to drive him out to the site where he took Saskia. That site? A wooden coffin six feet under the ground, where he’s buried alive. Rex cackling in terror and madness ends the film on a cold ironic note, as Raymond proves all-too-true to his word.

The Vanishing, of course, cannot have the credits roll with Kiefer Sutherland screaming in a coffin. So it makes up this tortured phony-kidnapping scheme involving Rita supposedly taking Barney’s daughter in order to get some leverage on him. It’s all profoundly stupid and insulting, leading to an inevitable bloody struggle where Rita furiously digs up Jeff from his fresh grave while assuming, wrongly, that Barney is incapacitated. Wiping the mud from his face, Jeff regains consciousness in time to pull Barney away from Rita and perform radical orthodontic surgery on his face with a shovel. Perhaps Sluizer expected American audiences to “scream and gasp” in their childlike way, but the film’s box office returns suggest otherwise.

The Vanishing ends in a coda where Jeff meets with a publisher who’s extremely interested in him turning his experiences into a bestseller. But first, the waiter brings over two cups of coffee, which they wave away. “We don’t drink that anymore,” they say with a laugh. Sluizer might as well have ended with a freeze frame.

With Travis, Krabbe, and Bullock mentions, this column couldn't be more early 90s if it was starting to appreciate grunge. Also realized that at times I combine Todd Graff and Todd Field, which is a horrible injustice. (Though Graff is fun in Five Corners.)

I watched Spoorloos on a bad VHS and it still hit like an icepick and I wasn't well-equipped to process it at the time. But remember the Vanishing ad on TV a lot and it included a shot of a dirt-smudged Travis saying something along the lines of "let's get this fucker" and knowing it was going to be crap. There's a special condescension that some European directors bring to dumbing things down for us American morons. Don't get me started on Haneke's smug Funny Games bullshit. Verhoeven may be the only one to really pull it off by critiquing and delivering simultaneously; possibly because he's enough of a vulgarian to also appreciate the joys of pulp cinema. I don't mind it when that attitude leads someone to pander beyond the point even the great unwashed will tolerate.

Saw this in the theater and I will say this for it: it was the first time I had ever seen Sandra Bullock on screen and a friend and I both fell in love with her immediately (I think we were both 18). She had a quality that leapt off the screen and her subsequent career is totally understandable.

Otherwise, yeah, that ending didn’t work even back then, when I hadn’t seen the original and Bridges (who I also love, like he was family at this point) practically had a flashing neon “WEIRDO!” sign above his head. And you almost need an explanation for what must be some personal damage that causes Travis to continue being in this situation.