The Summer of Cyber

In 1995, a quartet of techno thrillers offered some dire, if confusing, warnings.

The cinematic heroes of the summer of 1994 attempted to defuse bomb-laden buses, confronted scheming uncles with designs on taking over a pride of lions, and searched for Curly’s gold. They rarely touched keyboards, even more rarely entered passwords, and never stared down ominous, crudely animated avatars. By contrast, the summer and early fall of 1995 was filled with stories of internet intrigue, virtual reality baddies, and other perils of the wired world to come or, in some instances, already here. There had been web- and VR-inspired thrillers before 1995 — Lawnmower Man, the TV miniseries Wild Palms, and Disclosure, to name a handful — but whether the result of a culture shift or screenwriters drawing inspiration from a then-new magazine called Wired, 1995 marked a turning point, the moment when Hollywood movies acknowledged that we now lived in a world reshaped by the internet — even if neither movies nor moviegoers knew exactly what that meant.

Taken as a whole, the four cyber-thrillers that premiered between March and September of 1995 play a bit like the parable of the blind men attempting to describe an elephant (albeit an elephant that made the squawking sound of a 28.8 Kbps dial-up modem). From the perspective of nearly three decades on, it’s easy to mock all they got wrong about a chapter of history that was just beginning in the mid-’90s. It’s also worth noting what they got right, at least in part. And while the mini flood now looks like the product of an of-the-moment trend — it’s unlikely that both stars of Speed, a hit the previous summer, would end up in internet-focused stories if Hollywood didn’t suspect computer movies were the next big thing — each on its own is attempting to make sense of the rapidly changing times.

So where were we headed, according to the movies of 1995? Per the first to arrive, we were on our way to a grim future — 2021 specifically — in which gargantuan corporations controlled the flow of information and everyone lived in fear of a disease with no apparent cure. But if Johnny Mnemonic, released in May, is right about what the early 2020s would be like in the broad strokes, it’s less on-target with the specifics.

Keanu Reeves stars as Johnny (last name unknown), a “mnemonic courier” who carries data in an implant placed in his skull. To make room for it, Johnny has had to temporarily surrender the chunk of his brain that stores his childhood memories and, as the film opens, he’d like to get it back. That means taking one last big job, one that requires him to stuff more data in his head than it can safely hold and make the journey from Beijing to the “free city of Newark,” a kind of no-man’s land that’s home to both mammoth corporations and the rebellious Lo-Teks, a group who’d like to turn the current system upside down (and maybe find a cure for the dread plague of Nerve Attenuation Syndrome in the process).

It’s fitting that a season of online thrillers would kick off with an adaptation of a 1981 story by William Gibson, the science fiction writer who coined the term cyberspace and whose fiction anticipated both the possibilities and the darker applications of the technology to come. Yet while Gibson penned the screenplay to Johnny Mnemonic, a film whose impressive pedigree includes artist Robert Longo making his first (and to date, only) feature film, Johnny Mnemonic loses the sense of melancholy and alienation that sets his writing apart, opting for cartoonish (if mostly entertaining) sci-fi action in its stead. It’s telling that even adapting his own work, Gibson runs into the perils that make him so difficult to adapt. Depicting weird tech is a lot easier than portraying the effects of such tech on the soul. (Prime Video’s series The Peripheral has come closest.)

Some of the weird tech does look pretty silly now. Then again, it looked kind of silly in 1995, too. Johnny’s VR headset and “data gloves” seem prescient (even if the elaborate rig attached to them does not), but the depiction of the 21st century internet as a kind of buzzing cityscape made of video graphics looks like a cross between the cover of Billy Idol’s ill-fated Cyberpunk concept album, Homer’s adventures into the 3D world in The Simpsons’ “Homer Cubed” and The Mind’s Eye, the computer animation compilation video I used to rent to stoners when I worked at a video store in the ’90s. It’s a vision of the future that looked a little antiquated and janky even at the time

.Johnny Mnemonic’s technological skepticism now looks pretty sound, however, particularly in contrast to some of the high hopes and high spirits found elsewhere in the era. The early days of the internet doubled as the high-water mark for a cyber-utopianism that hasn’t proven out. It’s all over Hackers, a September 1995 release that serves as a kind of unintentional bookend to Johnny Mnemonic. Fresh off Trainspotting, Jonny Lee Miller plays Dade Murphy, a.k.a. “Zero Cool,” a.k.a. “Crash Override,” a teen whose preternatural computer skills made him a legend in hacking circles when he nearly crashed the New York Stock Exchange as an 11-year-old. Forcibly removed from computing until his eighteenth birthday, he reenters the hacking world at the same time he transfers to a New York high school that seems to be the center of the hacking universe, thanks to the presence of cool hackers like “Cereal Killer” (Matthew Lillard) and the bewitching “Acid Burn” (Angelina Jolie).

Hackers depicts hacking as an edgy subculture based less around lonely sessions at the keyboard than cool clubs filled with pulsing electronic music. It also treats it as an unabashedly righteous pursuit. Dade and his friends discover they’re the only force that could stand up to a skateboarding, trenchcoat-wearing hacker named “The Plague” (Fisher Stevens), the apparently rare hacker sell-out who’s planning to use his skills to orchestrate an environmental catastrophe that will be advantageous to his evil corporate employers.

Standing up to him involves web-surfing (again depicted as a journey into a kind of digital neon cityscape), rollerblading, phone phreaking, and mob action. The details are all very much of the film’s moment, but it’s the latter that makes Hackers look like the most 1995 cultural product this side of a Letters to Cleo tattoo. When our hacker heroes (previously seen disrupting a hateful right-wing broadcast filled with racist invective) put out a call to hackers far and wide, they’re met with cooperation as everyone unites for a good cause. Directed by Iain Softley and written by Rafael Moreu (who immersed himself in hacker culture as research and seemingly emerged a true believer), the film anticipates the internet’s potential as a tool for activism while ignoring its potential to be used as a loudspeaker for hate and harassment. Sometimes it’s not the bad guys who get swarmed. It’s a lot easier to be optimistic about a new development at its advent than after it’s had some time to show how it really works, and how much damage it might do. The hackers favor slogans like “Information is Penetration” while seemingly remaining unaware that there’s more than way to read those words

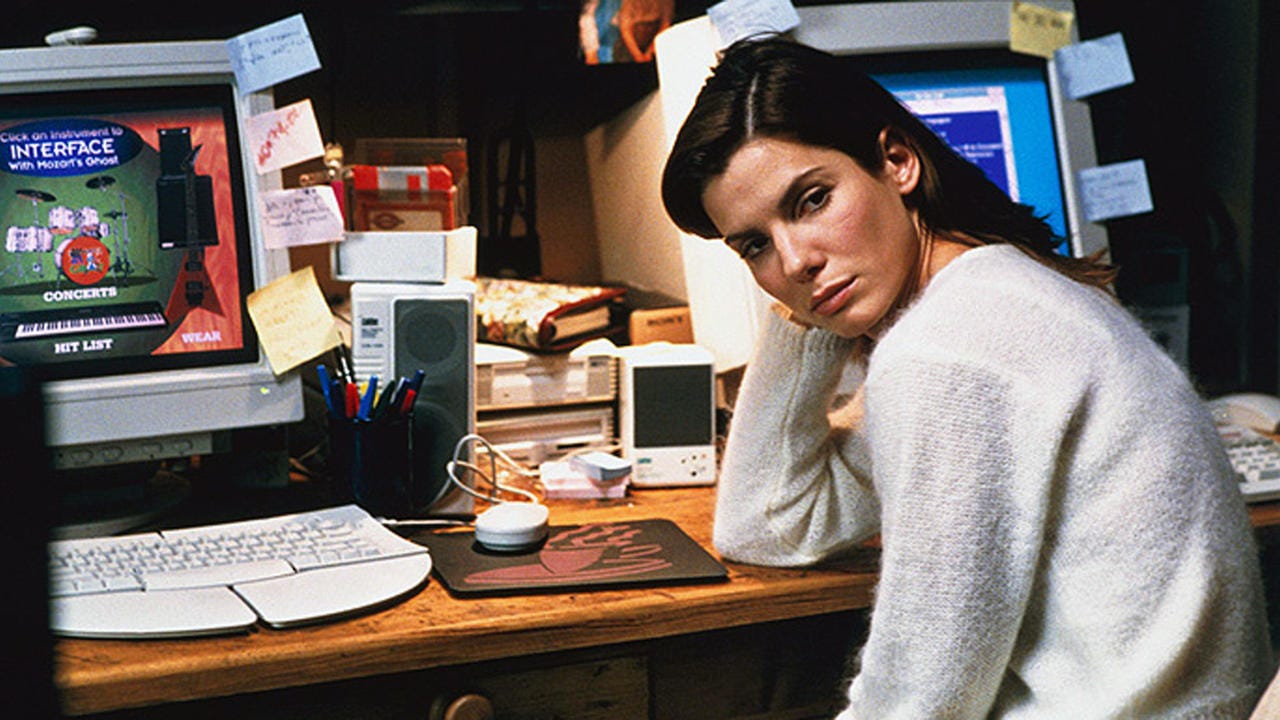

.The internet of Irwin Winkler’s The Net, is pretty much nothing but damage. Directed by Irwin Winkler, the late-July release essentially attempts a 2.0 upgrade on ’70s paranoid thrillers, but manages to get a few things right about the future in the process, starting with a work-from-home heroine who’s more comfortable chatting online than making face-to-face contact with other humans. A mildly de-glammed Sanrdra Bullock (she wears a flannel shirt in early scenes) stars as Angela Bennett, an ace systems analyst so isolated from the rest of the world she even orders pizza via a website. (Who could imagine such a thing?) But Angela finds her life is in danger when her latest assignment, debugging a not-very-fun-looking game called Mozart’s Ghost, opens up a portal to an underworld of shady doings.

The Net’s best moments arrive early, and not only because many of its later scenes feature Dennis Miller. While vacationing in Mexico — though Angela’s idea of relaxation involves bringing a laptop to the beach — Angela meets the dreamy Jack Devlin (Jeremy Northam), a fellow computer enthusiast who shares her taste in cocktails (gibsons) and movies (Breakfast at Tiffany’s) and who just generally seems too good to be true, even if Angela doesn’t realize this until moments before Jack tries to kill her. He’s like a flesh-and-blood version of Ex Machina’s Ava, a walking compilation of Angel’s desires. He also offers an early warning that any information we post online can and frequently will be used against us.

Information may want to be free, to paraphrase another popular slogan that had taken root by 1995, but could information develop such an overwhelming desire for freedom that it escapes from virtual reality into the material world? That’s the premise of Virtuosity, in which Lawnmower Man director Brett Leonard revisits some familiar virtual territory with a bigger budget (if no more impressive results). Set in a not-so-distant future Los Angeles where Parker Barnes (Denzel Washington) is serving time in prison after killing a terrorist who’d imprisoned his family (and a few innocent reporters in the process). But Barnes gets a shot at freedom when SID 6.7 (Russell Crowe), a VR character created by blending together the personalities of hundreds of criminals (including John Wayne Gacy, Charles Manson, and the terrorist Barnes killed), finds his way out of the simulation and into the real world.

Released to little success in the heart of the summer of 1995, Virtuosity is in many respects the silliest of the year’s cyber thrillers. It looks more misguided than forward-looking even in a moment where new VR headsets and the threat of artificial intelligence dominate the headlines. But maybe it’s still ahead of its time. Crowe plays SID with a gleeful malevolence that borders on camp, but who’s to say that when Chat GPT finally takes corporeal form and goes on a killing spree it won’t have flair and a sense of humor? We're now deep into an era that was only beginning in 1995, but there’s no suggestion that we’re anywhere near the end of it, or that we’ve seen every possible downside to the technological breakthroughs of the past few decades. Today’s sci-fi camp could be tomorrow’s nightmare come true.

A quick note about STRANGE DAYS: Obviously that's a big one from 1995 and there's more going on in that one than in any of these so I narrowed the focus. Scott, Genevieve Koski, Tasha Robinson and I covered it in a Next Picture Show bonus episode a while back: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/missing-movies-strange-days-1995/id1057714949?i=1000536104118

It’s Laser Age 2.0! Great piece, even if the only one of these I’ve seen (in theaters, no less) is Johnny Mnemonic. I even bought Gibson’s published screenplay for the college friend who convinced us all it was going to be the coolest thing ever.