The Short Goodbye: The Disappearing of 'Let It Be'

Disliked by the Beatles and released to a confused public mourning the band’s break-up, Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s documentary has been pushed to the margins for decades. But is that treatment deserved?

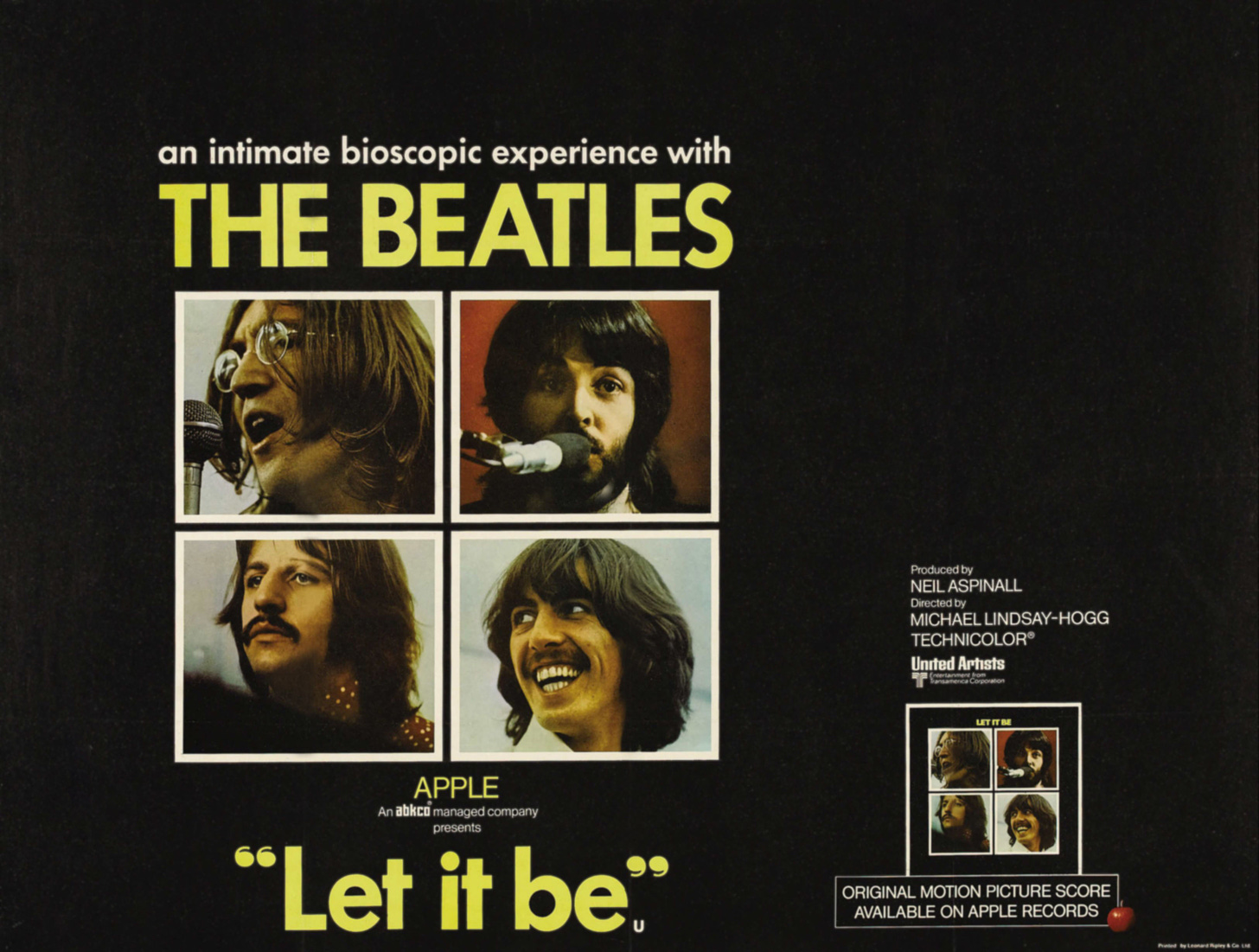

By the time Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s Let It Be reached theaters in May 1970, it had been transformed into light from a dead star. Shot in January of 1969, the film began as a documentary intended to accompany a TV concert. But the concert fell apart, and both the resulting movie and its accompanying album lay in limbo for months after their completion. Meanwhile, the Beatles recorded and released one last LP, Abbey Road, then broke up. Their long-rumored split was more or less confirmed by Paul McCartney in April 1970 as he released his first solo album, even if the band would remain an entity on paper for a few more years. When Let It Be premiered, first in New York, then in London and Liverpool a few weeks later, no Beatles showed up. Who walks a red carpet to watch footage of their own divorce? There was, in effect, no more Beatles. Lindsay-Hogg made a film of something that no longer existed.

In time, it would come to feel like his film didn’t exist, either. Though often excerpted and incorporated into other documentaries—particularly its climactic footage of the Beatles unexpectedly playing together on the rooftop of the Apple building in what would be their last public performance—the film itself has long been unavailable. Released on VHS and Laserdisc in the early ’80s, it’s been out of print ever since (even though Beatles fandom has turned it into one of the most bootlegged movies ever made).

The Reveal is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to bringing you great essays, reviews and conversation about movies (and a little TV). While both free and paid subscriptions are available, please consider a paid subscription to support our long-term sustainability.

And it’s likely to stay that way. Assembled from hours of footage shot for Let It Be, The Beatles: Get Back, Peter Jackson’s three-part, six-hour docuseries—which premieres on Disney+ this week—appears to be less an extended version of Let It Be than a corrective. Though it’s said to feature dramatic incidents not included in Lindsay-Hogg’s film—like George Harrison’s temporary departure from the band with the words “See you around the clubs” and John Lennon’s suggestion they could just swap Eric Clapton in to take his place—it’s also arriving amidst spin from Jackson and the surviving Beatles about how the additional footage captures the fun and joy of the collaboration not seen in Lindsay-Hogg’s film. Sure, the band would soon fall apart, but it wasn’t all bad times, even at the end! Speaking to Rolling Stone’s Brian Hiatt recently, Lindsay-Hogg seems genuinely sanguine about Jackson’s re-do. “The original thing exists,” he says, “and I know what I think of the original thing.”

But, like the proverbial tree falling when no one’s around to hear it, does a movie that takes such great effort to watch really exist? Talk of giving the original Let It Be a proper re-release remains, at this point, just talk, much as it has been since a 1992 restoration of the film and rumors of possible DVD-era editions. Get Back arrives accompanied by a book and a seemingly exhaustive (and excellent) super-deluxe version of the Let It Be album filled with discarded songs, outtakes, and alternate mixes (let the Glyn Johns vs. Phil Spector argument begin anew). Let It Be, the film, however, remains in a kind of limbo, likely destined to be overwritten by Jackson’s more expansive, band-approved version of the story.

But it’s also remarkable in its own right, a chaotic document of a chaotic moment captured with uncomfortable intimacy. A multitude of tensions—the result of well-documented business disputes, new romantic relationships, creative dissatisfaction, hard drugs, and general exhaustion—accompanied the Beatles as they came into the project. Let It Be was supposed to help ease those tensions, to reconnect them with the joys of playing together as a band after the frayed nerves exposed by recording the eponymous 1968 release usually called The White Album as they also figured out just where they fit into a rootsier music scene that had moved past the psychedelic era Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band had catalyzed. That was a good idea, but dubiously executed. Why anyone thought this reconciliation could be accomplished while rehearsing and working out new material on a film studio sound stage, being followed by a camera crew, and under the pressure to mount a TV special remains one of the great Beatles mysteries, as does what might have happened if there had been a more intimate sort of attempt to resolve their differences.

Nonetheless, there was no one better cut out for the job than Lindsay-Hogg. The director had a track record both with the Beatles and bringing music to television. He’d gotten his start helming episodes of the influential British music show Ready Steady Go! and the Rolling Stones’ 1968 Rock and Roll Circus special. He’d also directed the music videos for “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” making both the director and the band pioneers in a form that would become increasingly important to the music business. He was the right man at the right time, even if the times were bad.

Lindsay-Hogg’s approach to the recording scenes earned criticism at the time of release. “The film is a bore,” Tony Palmer wrote in the London Observer at the time of its release. “It's supposed to show how the Beatles work, but it doesn’t. Short without any design, clumsily edited, and defeatedly titled ‘A Feature Film,’ uninformative, awkward and naive, it would have destroyed a lesser group.” Palmer, unlike Lindsay-Hogg, seems to miss that the Beatles were busy destroying themselves and that’s the story being told by the film. In Let it Be, McCartney is impatient and demanding (but, of the four, seems the most interested in getting something done). Harrison becomes snippy in response. Lennon practically rolls his eyes during a run-through of what would become “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” (Lennon would reportedly categorize it alongside “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” as an example of McCartney’s “granny music.”) Other times, he seems checked out. Yoko Ono’s gaze never leaves her husband’s face. Ringo Starr mostly just drums away.

Shot vérité style with no voiceovers or interviews, the film features some telling visual compositions. Lindsay-Hogg often frames McCartney, Harrison and Starr together while Lennon remains out of shot. Meanwhile, Lennon and Ono are seldom seen without one another. McCartney frolics with his stepdaughter. Lennon and Ono neck and dance together. Songs start to come together then fall apart. And is the half-eaten granny smith apple, the embodiment of the band’s corporate logo, seen on McCartney’s piano a symbol or just a discarded snack?

There’s a second part of the story, however. While playing “One After 909,” one of their earliest collaborations, Lennon and McCartney find they can look at each other again. The footage of the Apple rooftop concert has an altogether different feeling. The band sounds great. Here they were showing up unexpectedly to delight unsuspecting Londoners in the middle of the afternoon, playing stripped down songs that signaled a willingness to keep exploring new directions as a group. They were a band with nothing to prove but they proved it anyway. They passed the audition.

Then, after recording one last album, they fell apart. Knowing this makes that rooftop triumph even more poignant. Here are old friends putting differences aside to play together, and play together wonderfully, though it’s clear that it can’t last. Let It Be’s 80-minute running time makes that climax all the more effective. The film drags on at first, capturing the boredom and tension of the recording process before building to moments of joyous performance. Then, all of a sudden, it’s over, and Lindsay-Hogg freeze frames the band leaving their instruments behind as the screen reads “The End.”

Lindsay-Hogg’s Let It Be is not the final word on this chapter of Beatles history, nor does it attempt to be. It’s a first draft of history, offering impressions of the band’s unstable but potent chemistry in its late stages that are more suggestive than revealing. It will be fascinating to see what Jackson unearths for Get Back (and what it looks like, given the CGI-enhanced restoration Jackson is employing for the project). Jackson’s film seems like a worthwhile, revealing project in its own right. But it’s unfair to push Let It Be to one side in its favor. This might not be the version of their last days that the Beatles want to stand as history, but it’s still a version of those days that deserves to exist, one made by a filmmaker in the thick of it and tried to capture the way discord could give way to music, at least for the length of a lunch break on windy winter afternoon.

> They were a band with nothing to prove but they proved it anyway. They passed the audition.

What a great line.

Me upset about Let It Be going down memory hole, but me also glad to hear Get Back give us more moments of Beatles rediscovering joy of being in this band.

That being said, any film about band, whether documentary or biopic, have to wrestle with problem of band approval. Me wish we could still see Let It Be, even as companion piece to Get Back, and me wish even more we could have seen Sasha Baron Cohen take on Freddie Mercury which was nixed by band. (Apparently surviving members of Queen wanted to make movie where Freddie die halfway through and rest of movie is about them soldiering on with series of lesser frontmen!) And me not know how to balance people's right to have some say over how their story get told, and audience's desire to get unvarnished truth of story.

It's a similar situation with the documentary-style books too. The new one you referenced, edited by John Harris, is a glossy, authorised, coffee-table effort, effectively an edited transcription of the audio tapes. A similar, unauthorised work by Doug Sulphy and Ray Schweighhardt, originally published in the '90s, I vaguely recall being absorbing in its grim, monochrome monotony.

Like Lindsay-Hogg's film, the earlier book is hard to find - in terms of UK availability, it appears just a single copy currently exists on ebay, yours for a mere £100 - but it would be interesting to compare that work to this new approved version.

Personally, the ANTHOLOGY project was sufficient for me to be dubious of any nostalgia project, mono reissues aside, the b(r)and has been directly involved with.