The Quaffable Whines of Alexander Payne and Paul Giamatti

In 'Sideways' and 'The Holdovers,' director Alexander Payne brings out the richest flavors from the temperamental vineyard of Paul Giamatti.

The first utterances we hear from Paul Giamatti in Sideways and The Holdovers, the two comedies he’s made with director Alexander Payne, are not words but exasperated sighs, as if Hades has presented him with another goddamn boulder to roll up the hill. These small cries of existential despair are his defining trait, usually prefacing a sarcastic response to a world that constantly disappoints him—which, of course, is a cover for the disappointment he carries about himself. As a younger man, he might have imagined a destiny worthy of his considerable intellect and his hidden capacity to love, but now he’s middle-aged and lonely, and the few who regard him at all mostly regard him as a failure or a dyspeptic pain in the ass. It takes narrative interventions to pull his characters out of these ruts, because he certainly doesn’t have the ability to do it himself.

Miles Raymond in Sideways and Paul Hunham in The Holdovers are not exactly the same character, but they probably grouse together famously over a pipe and a bottle of fussily snorted-over California pinot. They are both teachers of unenthusiastic students. They are both authors of brilliant books that are either unpublishable (Miles) or theoretical (Paul). And they both have to break out in a sprint at one point in the movie, because Payne correctly believes that it’s funny to watch Paul Giamatti run. But the true connective tissue between these movies and these performances is a temperamental hero who really does deserve happiness, despite all indications to the contrary. Miles and Paul are not easy men to love, but Payne and Giamatti believe their cynical, world-weary response to the world is understandable and that they’re worth the difficult effort to get to know.

Though Sideways and The Holdovers takes place on separate coasts—one opens in a crummy apartment building in San Diego, the other in a snow-caked boarding school in New England—Payne is an example of how you can take the boy out of the Midwest, but you can’t take the Midwest out of the boy. Though films like Election, About Schmidt, and Nebraska don’t stray far from Payne’s native Omaha, his attentiveness to the grinding banalities of everyday life seem regional even when he’s shooting in other locations. It starts with the exceedingly lived-in interiors of both men, who are first shown wearing clothes—Miles a ratty bathrobe and slippers, Paul a fedora and bowtie—that are probably as old as their students. Neither one of them would concede that the world has evolved past them, exactly, but time has certainly taken its toll.

Beyond those initial grumbles, Payne introduces these men with private, cranky invective. In Sideways, Miles has overslept the morning he’s supposed to pick up his old college buddy Jack (Thomas Haden Church) for a week-long trip through Santa Barbara wine country before Jack’s wedding the following weekend. He wakes up to his landlord pounding on the door, telling him his car is parked in the movers’ spot. In The Holdovers, Paul is using words like “philistine” to describe the essays he’s marking up for his Ancient Civilizations course, which he has designed as a kind of a speed bump for the boarding school brats at Barton Academy en route to their legacy admissions at an esteemed university. If he does his job really well, perhaps some of them will have to opt for their safety schools instead.

Though both films would seem to be about the audience, along with the other characters, learning to love this prickly pear of a man, Payne and Giamatti align us with Miles and Paul from the beginning. Before Miles gets around to picking up his friend in a weather-beaten ’87 Saab 900, Payne gives us a glimpse of his priorities: He reads a book on the can. He stops for a spinach croissant and a New York Times at the coffee shop. He works on the crossword puzzle in pen while he negotiates the freeway. We can see that Miles is an intellectual with a taste for a finer things, and this is before he launches on one of his showy disquisitions on wine tannins and grape varietals or expresses his contempt for local Cabernet Franc or “fucking Merlot.” This is not your typical slob. This is a slob worth getting to know.

Paul is a harder case, but only slightly. Over Christmas break leading into the new year of 1971, Paul has been asked to stay on campus with the small handful of students whose parents have opted not to pick them up for the holidays. In theory, these are kids he should like, because he himself is a Barton Academy alum who came back to teach and now barely leaves campus, much less travels to loved ones anywhere else. But he’s all too happy to absorb the hatred of his students and colleagues because he sees them all as hopelessly entitled and he doesn’t mind making things harder on them. Paul knows the headmaster is punishing him for failing the son of a wealthy school donor, but he’d rather take the abuse than compromise. There’s pettiness in that, no doubt. But there’s integrity, too.

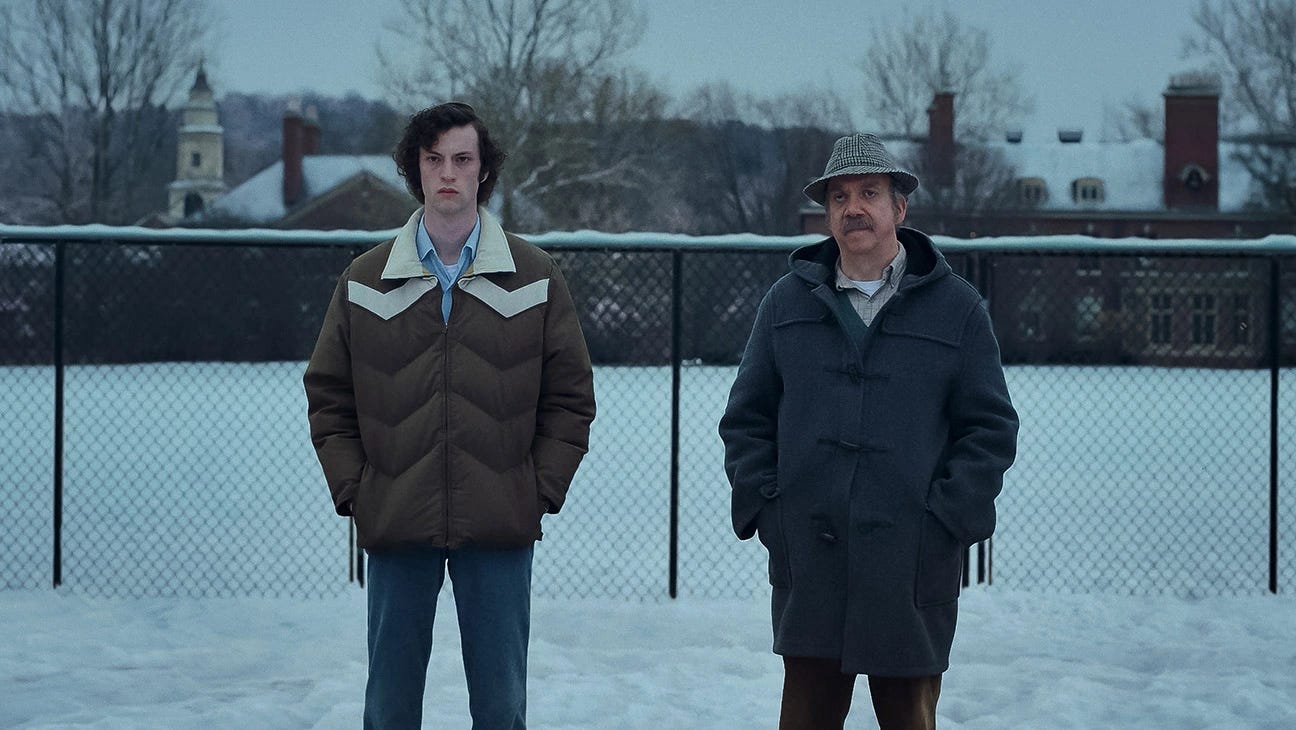

Sideways and The Holdovers pair Giamatti with a sparring partner who both stokes his comic irritation and brings out the decency and heart that isn’t so easily noticed. To Paul, Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa) doesn’t initially seem so different from a typical boarding school shit, beyond being the only boy to turn in passable essays in his Ancient Civ class. But when the other four students under his supervision are whisked away, leaving only Angus and Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), the school’s cafeteria chief, for company, a bond starts to develop between Paul and Angus. Paul is deferential to Mary, who has just lost a son (once one of Barton’s conspicuously few Black students) in Vietnam because she couldn’t afford a college deferment. But Angus is being left behind at Christmas for a reason and it becomes increasingly clear that the two men have some things in common.

Though both films are more or less comedies, Sideways fits the classification more snugly, offering Miles and Jack as supposed best friends since college who more likely didn’t make any good friends after graduation. Miles wants to take Jack on a spin through his favorite wineries and restaurants and maybe get in a little golf, but Jack is itching to sow his wild oats before tying the knot. The one common goal they share is to drink a lot: While Miles has the more sophisticated palate—one great running joke is Jack nodding his approval over every wine they sample, no matter his friend’s learned judgment (“Quaffable but far from transcendent”)—it’s often a cover for his tendency to drink to excess. When Miles plans out the trip, where they go and where they stay relates to limiting the amount of drunk driving they’ll have to do.

A lot of the comic tension in Sideways comes from Miles and Jack working at cross-purposes: Jack wants to get laid and Miles is repulsed by having to serve as his wingman. When the two of them find great women to spend time with, it’s Jack who hits the accelerator by making promises to Stephanie (Sandra Oh), a wine-pourer and single mother, that he cannot keep. He has cold feet, so he lies to himself, too, about moving out there with Stephanie and starting a winery with Miles. Meanwhile, Miles reconnects with Maya (Virginia Madsen), a waitress and soon-to-be horticulturalist who has everything in common with him. But Miles is clumsy and out of practice—he steps on an opportunity to kiss Maya that even a clammy-palmed adolescent boy wouldn’t miss—and he’s preoccupied with an ex-wife who’s getting remarried.

The beauty of Giamatti’s performances in Sideways and The Holdovers is that he’s playing characters who are hilariously snarky and self-absorbed, but not so entirely wrapped up in their own nonsense that they can’t give other people consideration. It genuinely bothers Miles that Jack is out in wine country cheating on his fiancée, and when Maya confronts him about it, he says, “I’m not Jack. I’m his freshman-year roommate from San Diego State.” And while much is said about the lovely speeches Miles and Maya offer about their oenophilia—Jack’s line about pinot grapes being “thin-skinned and temperamental” are like a copy-paste of his character description—Giamatti’s best moment in Sideways is mostly nonverbal. When Miles finally sees his ex-wife outside of Jack’s wedding and she tells him that she’s pregnant, Giamatti pulls off an expression that suggests that he’s utterly shattered by the news yet willing to suppress his disappointment to congratulate her. He will have time to soak in his misery later, when he pops open his prized Bordeaux over a desultory burger and onion rings, but he will mask his feelings for her benefit.

Some of that generosity of spirit emerges, too, in The Holdovers, particularly Paul’s instinct to protect the grieving Mary from teenage boys who don’t care to know her beyond griping about her cooking. It is to Payne’s credit—and to Randolph’s performance—that Mary doesn’t need a guy like Paul to look after her so much as commiserate with her and share a little liquid cheer. There’s a real sincerity to Paul’s class-consciousness: He may be guilty of failing to make his passion for history come to life for students and perhaps punitively targeting them for his own disappointments, but the failure of a school like Barton to shake these boys from their rich-kid insularity irks him, as it should. When he finally realizes that Angus doesn’t fit into this box, a camaraderie develops between them that’s arguably deeper than Miles’s longstanding relationship with Jack. At the very least, it sparks a nobility in Paul that’s extremely moving.

With its allusions to ’70s cinema, particularly Hal Ashby films like Harold and Maude and The Last Detail, The Holdovers feels like entering a time machine and experiencing Payne’s vision of an American studio film from that era. And even though Sideways is more unadorned and contemporary, Giamatti’s presence in both films signals a different type of movie star, too, who may align more with people we know. Miles and Paul speak to how we feel at our loneliest and least understood, when we carry some private pain that can be muted by fine liquor yet quietly yearn for affection or, at a minimum, to be seen. That’s a hero worth rooting for—and one increasingly hard to find.

Such a fine comparison between these two wonderfully warm films. The Holdovers is simply one of the best movies I've seen this year. It's funny -- my wife and I were watching Sweet Smell of Success the night before, and every single character in that movie is just an odious human being! The Holdovers is pretty much the exact opposite; the characters are faulty as hell, but they're all such good people inside.

This film hits so many of my soft spots: academia, winter break, snow, Christmas, New England. Every time one of the characters said something unusual or difficult ("hidebound" was the first one, I think) and another would say, "I know what that means" made me laugh out loud. It happens like three or four more times!

The writer must've had fun with the character names:

Hunham - almost sounds like throat clearing

Angus - angst

Mary Lamb - caretaker

Lydia Crane - you think she's single (one leg), but she's not

Kountze - Geoffrey Chaucer's "quaint", modernized and slightly obfuscated

Hardy Woodrup - a punchable name if there ever was one

Am me only one who read pinot noir speech as Miles making realizing that maybe he not have enough good qualities to outweigh bad, even as he arguing opposite? Me feel like ending of that movie is Miles stripping away his delusions of grandeur — he not brilliant novelist, he not pinot noir — and accepting self for who he is, mediocre grade school teacher and alcoholic who not have better place to enjoy his fancy bottle of wine than booth of fast food joint. Now, that not exactly uplifting ending, but it one me love.

That kind of clear-eyed harsh clarity is rare thing in movies, but it incredibly satisfying. It remind me about what someone — probably one of you two or Tasha — said about James Caan at end of Gambler. He's pissed away whole life seemingly for no reason, but real reason is that deep down, this is who he is, and he finally comes to understand that. Miles come to similar — if less self-destructive — realization at end of Sideways. Or at least, that how me always read that ending.